|

||

Vol. I, No. 1

Vol. I, No. 2

|

Index of Posts Relating to Features

Dr. Johnson’s St Andrews LamentSamuel Johnson and his Scotch companion James Boswell embarked for Scotland ‘in the autumn of the year 1773’, and their excursion was written up by Johnson as A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland (1775). This classic travel book contains a fascinating entry for St. Andrews. “St. Andrews seems to be a place eminently adapted to study and education… exposing the minds and manners of young men neither to the levity and dissoluteness of a capital city, nor to the gross luxury of a town of commerce, places naturally unpropitious to learning.”

The Scottish tour provided for Johnson what has been called ‘a realm of experience foreign to the Enlightenment illuminati of London and Edinburgh’. Johnson said simply, ‘I saw a quite different system of life.’ Shades of the Scottish past darkened in distinct bands as Johnson and Boswell journeyed north – beyond Inverness was ‘a much harsher world’, which manifested itself both in difficulty of travel and in the destruction wrought by the Highland clearances, which had swept away the ancient Gaelic speaking culture that had existed from the Highlands to the Islands of Scotland. But Johnson began his tour in the civic Scotland of the east coast, passing from Edinburgh to St. Andrews, and then to Aberdeen. If the northern regions revealed a half-forgotten Gaelic past, St. Andrews was a relic of Catholic Scotland, formerly pious, learned, and grandiose. Johnson found a cathedral ruined, locals carrying away its stone for their own houses, the whole site cluttered with rubbish, and a mad old woman living in a hole – but he saw beyond its decay and demise, that it had been once ‘a spacious and majestick building, not unsuitable to the primacy of the kingdom.’ Boswell recorded that “Dr Johnson’s veneration for the Hierarchy is well known. There is no wonder then, that he was affected with a strong indignation, while he beheld the ruins of religious magnificence. I happened to ask where John Knox was buried. Dr Johnson burst out, ‘I hope in the high-way. I have been looking at his reformations.’”

The university itself was in a parlous condition, entering its eighteenth century slump. Neither flourishing nor utterly ruined (as were the churches), Johnson saw the university ‘pining in decay and struggling for life’. As for numbers, against our six thousand, at the time of Johnson’s visit there were one hundred students – St. Mary’s divinity faculty capable, but not holding, fifty; and fees were £10 for poorer students. Though Johnson considered the town ‘a place eminently adapted to study and education’ still a sense of unease remained in his memory after the visit’s accidental pleasantries – he notes excellent hospitality – had been enjoyed. What are today admired as romantic ruins – the cathedral, the castle, St. Mary on the Rock –, Johnson saw, with greater insight, as ‘mournful monuments’ to a lost civilisation. (Incidentally, the one really impressive remain, St. Rule’s Tower, they completely overlooked.) Dr. Johnson concludes summarily: ‘The kindness of the professors did not contribute to abate the uneasy remembrance of an university declining, a college [St. Leonard’s] alienated, and a church profaned and hastening to the ground.’

February 1, 2005 12:15 pm | Link | Comments Off on Dr. Johnson’s St Andrews Lament

The Meaning of ‘Aardvark’

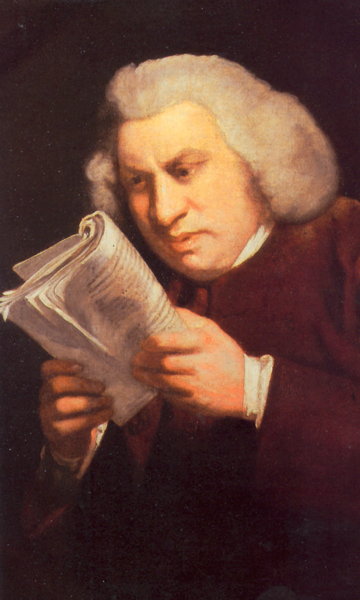

There was no comprehensive dictionary in the language, – only one by Nathan Bailey in 1721 which pathetically defined a mouse as ‘an animal well known’, revised after complaint to ‘a small Creature infesting houses’. Something more satisfactory was needed, and the task – proposed previously to Addison and then Pope – fell to Johnson, who in 1755, after nine years, produced a dictionary of 40,000 words, advertising itself ‘etymological, analogical, syntactical, explanatory and critical’. He would define mouse as ‘the smallest of all beasts; a little animal haunting houses and corn fields, destroyed by cats.’ Much better. Though 40,000 words is a fraction of the OED and indeed even less than Bailey’s earlier dictionary, Johnson’s word-hoard was far beyond a mere improvement. It was a giant leap in classification, schematically distinguishing between the senses of every word. Being a masterpiece of English prose, with definitions so pithy and correct that many are borrowed still by modern lexicographers (def. ‘a writer of dictionaries; a harmless drudge’), it remained the standard well into the nineteenth century. Only the philology of that century – which showed many of Johnson’s etymologies to have been fanciful – enabled the creation of a dictionary that surpassed it. The work was a triumph of scholarship, though admittedly with ‘a few wild blunders and risible absurdities’ (corrected in the 2nd edn.). It earned him the nickname ‘Dictionary’ Johnson, and the reputation as England’s foremost man of letters, living outside the universities and surviving on commercial success rather than a fellowship. However, the adulation was not universal. The dictionary did not go down well in Scotland, and a St. Andrews theologian and classicist called Archibald Campbell attacked ‘our English Lexiphanes, the Rambler’, ‘the great corrupter of our taste of language’, and his personal, political, and national dictionary. But this was in its way a tribute, for the Dictionary was a personal work – not the product of an institution, as were the 1612 Vocabolario of the Academia della Crusca, or the 1694 Dictionnaire of the Académie française. Johnson’s Dictionary of 1755 was the work of an individual animus and it shewed forth the man. The dictionary is famous for its succinct definitions and array of quotation, the latter chosen judiciously to illustrate the former. In search of exemplary usage, Johnson borrowed and defaced his friends’ books, and proclaimed that he had ‘extracted from his philosophers principles of science; from historians remarkable facts; from chemists complete processes; from divines striking exhortations; and from poets beautiful descriptions’. The result was that those authors selected as exemplary became with Johnson ‘authorities’ (the dictionary was an important step in canon-formation), and their example, for good or ill, standardised ‘good’ English usage. This act of codification made English a bit more like Latin and Greek, and a bit less wild and organic. Johnson was, however, criticised for airing his prejudices in a work of supposed scholarship, as when he famously defined Whig, ‘the name of a faction’, in contrast to Tory, ‘One who adheres to the ancient constitution of the state, and the apostolical hierarchy of the church of England, opposed to a Whig’. An innocuous word like oats became an opportunity to needle the Scots (especially Archibald Campbell), which he took up willingly: ‘oats. A grain which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people.’ Besides such cameos, the dictionary shows the prejudice of its age by ignoring mediæval literature in its quotations. ‘I have fixed Sidney’s work for the boundary beyond which I make few excursions’, wrote Johnson is his Preface. Shakespeare got in, as furnishing ‘the diction of common life’, but Johnson thought the English language was shown in its purity in Hooker, the King James Bible, Bacon, Raleigh, Sidney, and Spenser (all canonical works of early English Protestantism). Johnson’s authorities were post-mediæval but pre-Restoration. Quoting Spenser, he called them ‘the wells of England undefiled, … the sources of genuine diction.’ Pre-sixteenth century texts did admittedly lay largely unedited, in dispersed (if not destroyed) monastic libraries and great private collections, but still his canonical dictionary cut England yet further adrift from its mediæval heritage. Such a literary approach, basing English usage on great writers, differs from the practice of Johnson’s modern OED successors, but Johnson thought the lexicographer’s role was not to reflect common usage but to ‘correct or proscribe’ where he found linguistic ‘improprieties and absurdities’. As he explains in his fine Preface, he was not seeking to record the language but to improve it. Curiously, Johnson cited ‘no author whose writings had a tendency to hurt sound religion and morality’, and famously when congratulated by some ladies on excluding all the ‘naughty’ words, replied unsparingly, ‘What, my dears, then you have been looking for them?’ It has been pointed out to me that the ladies either did not find, or did not consider sufficiently naughty, the entries for ‘piss’ and ‘fart’. Consistent with his method of definition followed by illustration, the latter was accompanied by a quotation from Swift:

But for many the relative conservativism of the dictionary was not a virtue, and so as a symbol of her rebelliousness Becky Sharpe tosses a copy from her carriage at the beginning of Vanity Fair. I encourage all to take a brief look at the fine facsimile of the 1755 first edition, in two enormous volumes in the dictionary section of the University Library. The modern reader can certainly still enjoy Johnson’s magnum opus, though some definitions are abstruse, such as, notoriously, ‘Net: Anything reticulated or decussated at equal distances, with interstices between the intersections.’ As his biographer Boswell comments, critics found this guilty of ‘obscuring a thing in itself very plain.’

February 1, 2005 12:10 pm | Link | Comments Off on The Meaning of ‘Aardvark’

All That is Seen and UnseenDame Muriel herself is the major obstacle to reading her work. It is difficult not to become emotionally involved in the author, either with her narratorial voice, or with semi-autobiographical characters which portray Spark at various points in her life. The moral fluidity of Fleur Talbot in Loitering With Intent can depress a reader, especially a male one, into hating the character and, by extension, the author, with disastrous consequences if one wishes to continue reading her work. The feeling with Fleur when she justifies adultery or theft is like that of a child discovering that their parents or priest are imperfect. Spark is very much a deity in the world of her novels. Having said this, Dame Muriel’s novels are so rich and deep with the highs and lows of humanity that one must be brave if one is to experience the works of a lady who, I am convinced, will be seen as one of the great English language prose writers of the twentieth century. Dame Muriel was born in Edinburgh of a Jewish father and Presbyterian mother, attended a Church of Scotland (hurrah!) school, and became a Roman Catholic. She lived in Edinburgh, Rhodesia, London, and now Tuscany. She has been a poet, editor, mother, and a second world war intelligence officer. All this is encapsulated in her novels. Yet she is not an author who needs to pander to contemporary literary needs (rough sex, heroine spikes, poverty). She writes what she knows in a style which feels timeless. It is sometimes jarring to hear her describe the internet, for example. Indeed it is important to note that she started writing novels in 1958 when she was thirty-nine. Having lived through a failed marriage, childbirth, war, a mental breakdown, a conversion through the works of Cardinal Newman to Roman Catholicism, she was in a position to write novels of experience and authority, as well as a tender beauty, born out of suffering. She is still writing. To be some help to the reader who is interested in Spark’s novels, I will suggest three very different novels of hers to start on, according to taste, none of which are The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, classic though it is: The Public Image is one of Spark’s darker novels, curiously foreshadowing the explosion is the cult of the celebrity and the paparazzi phenomenon. Annabel Christopher is the latest hot British film star, with a writer husband and a head for PR. She cannot act. Yet Spark seems sympathetic to her major talent: she is the English tiger-lady, very much like Rosamund Pike’s role in “Die Another Day”. She is the beautiful, cultivated English mother, sophisticated and proper. Yet behind her wide eyes and away from the cameras she is an insatiable tiger in the bedroom. In real life Annabel Christopher is a pretty girl who got lucky and has very little time for sex, let alone insatiable tiger sex. The sympathy comes from her portrayal as a male fantasy. Her ruthless calculations in dealing with her husband’s suicide reveal her real inner strength. Although definitely not a feminist, Spark here creates a novel which is very scathing in its social implications, yet gripping and readable as any popular novel. For a lighter read, try Aiding and Abetting. This 2000 novel deals with Lord Lucan, supposing that he is still alive and seeking therapy. Except that in Spark’s world, there are two Lucans, each trying to prove that they are genuine. The therapist herself is a fake stigmatic, who made a fortune fooling the masses, and now has her own disturbing method of psychoanalysis. Much is made of Spark as a Catholic novelist, yet I think that this is a part of her work as much as any other part of her life is part of her work. Her perspective on the Church of Rome is, however, very interesting and is certainly something to think about when reading her novels. Aiding and Abetting has many examples of Spark giving clues to the reader, only to take the solution away from them until she feels that she should reveal it. It is this teasing aspect to her novels which is so seductive. One can read this as a top quality detective novel. Finally, I would suggest reading The Girls of Slender Means. Set in a second world war hostel for young ladies, Dame Muriel creates a novel which reflects humanity through the lens of these young girls working in London. Nicholas Farringdon has ambitions to explore the girls intimately, and ends of making them his idealised conception of society. His is trying to write a philosophical treatise among the chattering of debutantes and secretaries. This novel does contain examples of Spark’s wicked and wonderful humour, she as the chatter of the upper-class Dorothy Markham: ‘He actually raped her, she was amazed… Filthy luck, I’m preggers. Come to the wedding!’. There is always an ironic edge to Spark’s work, which will frequently have one laughing out loud. I do hope you will begin to read the novels of Dame Muriel Spark as they are such a treasure to the English language that it is sad to think of them languishing on bookshelves in need of a good home. There is always more to her than meets the eye.

February 1, 2005 12:05 pm | Link | Comments Off on All That is Seen and Unseen

|

Robert O'Brien Editor Matt Bell Associate Editor Andrew Cusack Publisher Founded in 2005 at the University of St Andrews in Scotland |