|

||

Vol. I, No. 1

Vol. I, No. 2

|

2005 February index

Thin on Plot, Not on EyelinerIt’s a classic tale: Macedonian lad with an affection for blond wigs and enough eyeliner to make a transvestite blush, meets horse stricken with fear of its own shadow. Boy and horse fall in love and express their love by together conquering the known world, until horse tragically dies in a death charge against Indian elephant. Beyond this, there is no getting away from the fact that ‘Alexander’ lacks a coherent plot. Oliver Stone’s opulent comeback film revels in its confusion, apparently attempting to divert any intelligent questioning by revealing Alexander to have, in fact, been an Irishman. But the film does unwittingly present a strong moral lesson. The only motivation for Hollywood to again abuse a topic from ancient history seems to be that Alexander represents a subject easily adaptable to pander to the cult of celebrity that permeates our popular culture. Of course Alexander was acutely aware of his place in history, but the thrill and fascination of his life is utterly lost with this all too human Alexander. Although Alexander gloriously trots around Asia killing lots of people for supposedly the best of intentions, parallels being drawn perhaps with America’s current foreign policy, you can’t help but think that he’d have lived an ultimately more fulfilling, though less famous, life if he’d stayed at home and found a good Irish/Macedonian wife to share his eyeliner with. Colin Farrell wallows in the reflected glory from the historical figure he perceives himself to be imitating, but it is this perception of mere fame and glory as the ultimate virtue that allows the film to become so reduced and ultimately pointless. The fact that ‘Alexander’ takes three hours to teach us the folly of its own ways, however, leaves you feeling somewhat cheated not only of your financial contribution but also of the portion of your life invested, now lost into the ether. The film is so painfully dull and protracted that when Alexander finally does die it seems the most lacking part. I think strangulation would have been more satisfying. Could Sir Anthony Hopkins not have spiced things up a bit, dropping the impersonation of Yoda visiting the great library of Alexandria, and donned his Dr Lecter persona once more?

February 1, 2005 12:40 pm | Link | Comments Off on Thin on Plot, Not on Eyeliner

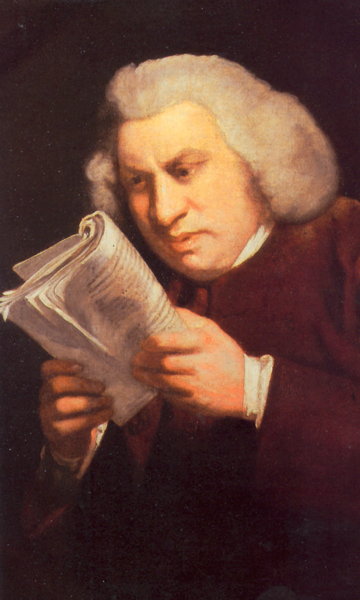

The Oxford Dictionary of National BiographyThe new Oxford Dictionary of National Biography was published in September, in sixty volumes, and consists of fifty-four thousand lives, written by ten thousand contributors, and under two editors. The project took just eight years to complete (1992-2004). It can be located in book form in the university library, or through an admirable web site (it nearly existed only online). It is undoubtedly a remarkable thing. But for those of a scholarly disposition, it is a monumental work to be surveyed with a mixture of wonder and rage. Until now, one used the Dictionary of National Biography, first published in 1901 by Virginia Woolf’s father, Leslie Stephen. It was well-written and insightful, but needed an update. To get into it, of course, you had to be dead – Queen Victoria timed her death well to get in, but some like Gerard Manley Hopkins and the peculiar Baron Corvo had also died well in good time, but were passed over. The DNB continued to publish supplements through the twentieth century, including a ‘Missing Persons’ volume in 1996, which filled these lacunae. The ODNB surpasses its predecessor at least in coverage, being 42% bigger, an increase reflected not merely in modern entries but across the centuries. Biography is the undoubted flagship of modern writing in English. Industries have arisen around certain figures (Dr Johnson enjoys what is known as a biographical literature), and writers plan ahead for centenaries of births, deaths, battles, and so forth. What is the present appeal of biography? Perhaps at its best the genre offers the narrative of a novel with the reassurance that the reader is still in ‘the real world’. The biographer is a sort of cross-breed, one half historian and the other novelist. But fundamentally, literary biography (or just plain biography) is the genre for high-brow gossips – that, if I may insult my reader, accounts for most of us. CriticismsNo-one thinks we would be better off without it, but the ODNB has come in for a bit of a hammering in the learned journals. In the London Review of Books, Stephan Collini gave the thing the thumbs up, and reminded us that he wrote 0.025% of it. But, despite the fact that what must be a sizeable proportion of the eminent academic population have a hand in it, and so have a vested interest in its promotion, there has been not only criticism from outside but also dissention in the ranks. Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Freeman UnleashArthur Freeman, who is responsible for two no doubt immaculate entries on the nineteenth century book-world, has submitted a damning, savage letter to the TLS (February 11, 2005). His criticisms are aimed at inaccuracies in numerous second- and third-rate figures, on whom the ODNB’s credibility must rest. For the really pre-eminent figures in the national memory, one need not turn to the ODNB (though there are many exemplary entries on the big names, such as Pat Roger’s life of Samuel Johnson). But, where, asks Freeman, is he to go to find out about William Chetwood or Thomas Lodge, but the ODNB? And when he does, what does he find but misinformation? A book he knows to have been in one volume, an ODNB entry says consists of several! A book exposed as a forgery in the 1960s, now attributed in 2004! Dear oh dear. Freeman says that in many places ‘the old DNB, while in need of an update, [was] vastly better’. Any more of this, and Harvard will be returning their three copies, Yale their two, and we at St. Andrews our one beloved set. These errors – and Freeman and his wife (also an ODNB contributor) seem to have done little else these last months but look for them – are worrying because the ODNB is sure to be a foundational reference tool for future generations. Elementary mistakes are to be frowned on, but at least the online version can rectify what errors there are. LeftismThen there is the other problem of politics and biases, pointed out by the superb Roger Kimball in the New Criterion. ‘Almost by definition,’ writes Kimball, ‘a contemporary academic project is going to exhibit a left-liberal, politically correct bias.’ John Gross in the TLS calls Colin Matthew (the editor who died half way through this venture) ‘a man of the Left’ though ‘his convictions were tempered by a certain cultural conservatism.’ Phew. In his review Kimball goes on to say that the leftism is not a serious detraction. One trend seems to be that most of the time entries are written by scholars sympathetic to their subjects. Ian Ker writes up John Henry Newman, and not, say, Owen Chadwick, and Simon Heffer naturally supplies a fine appreciative entry on Enoch Powell, when a liberal commentator might have been more damning. But then there are problems. Kimball picks on ‘Eric Hobsbawm’s comically laudatory, indeed, hagiographical article about Karl Marx’ and he with others have had problems with Peter Holland’s biography of Shakespeare. (Marx enters the ODNB under a new rule permitting foreigners who have influenced national life.) In both cases, leftism appears in rather crude openness. As for political correctness generally, women account for nearly 10% of the ODNB, as opposed to only 5% of the DNB. Some say this is too many, some not enough. I am not qualified to measure the contribution these women made to national life, but there is a tendency nowadays, in education and politics especially, to let the ladies win. If that is true, isn’t it rather patronising? ShakespeareTalking of leftism, lots of reviewers have picked up on Holland’s statement that ‘In Britain politicians of the left and right rely on Shakespeare as a national and quasi-religious authority for their political creeds. The Labour leader Neil Kinnock, the heir to nineteenth-century political oratory with its predilection for quoting Shakespeare, required his speech-writers to know the Bible and Shakespeare, the twin bedrocks of working-class culture. At the opposite end of the political spectrum, right-wing Conservative politicians like Michael Portillo returned with mechanical frequency to Ulysses’s speech on degree in Troilus and Cressida as “proof” that Shakespeare supported the hierarchies and institutions tories were committed to maintain.’ Thankfully the ODNB does not return to this sort of thing ‘with mechanical frequency’. I was more interested to see how Holland would present the matter of Shakespeare’s probable adherence to the Roman Catholic religion. Holland is, of course, entitled to doubt the evidence – but if he is to discuss the matter, he must present it fairly and not miss out anything important. Particularly odd is his treatment of the spiritual testament of William’s father, John, a document of the sort the English Jesuit missionaries distributed to Catholics as proof of fidelity to the Faith. The document was found in 1757 in the Shakespeare family home, Holland says by a man fond of forgeries. ‘In the unlikely event that it was genuine’, writes Holland, it would suggest the Shakespeare household was Roman Catholic. However, this is unlikely, as ‘[i]t was, after all, during John Shakespeare’s time as bailiff in 1568 that the images of the last judgment that decorated the guild chapel in Stratford were whitewashed and defaced as no longer acceptable to state protestantism’. Perhaps, Holland says, this was just more outward conformity. This is a peculiarly incomplete account. Patrick Collinson, of Trinity, Cambridge, has been recently arguing with Alastair Fowler on this matter, and makes the important point well. ‘According to Fowler,’ Collinson writes, John Shakespeare’s Protestantism is evidenced by the fact that as a Stratford alderman he “engaged in Protestant iconoclasm”. He did no such thing, and if he had we should not still be looking at that great doom painting in the guild chapel. Shakespeare saw to it that the image was covered with whitewash, which was not iconoclasm but, contrary to the Royal Injunctions of 1559, which spoke of removal and destruction, a means to preserve it, as real iconoclasts well knew.’ Go today to Stratford and you will see that William Shakespeare’s father was the most incompetent (or half-hearted) iconoclast in England. And perhaps, therefore, a Roman Catholic? There is much more evidence pointing to William’s adherence to what was almost certainly his father’s religion – apparent residence in a Catholic recusant house in Lancashire (‘groundless’ according to the ODNB), a signature in the English College, Rome, recusant links at William’s Stratford Grammar School, allusion to the martyred saint Edmund Campion in Twelfth Night, Hamlet’s father in purgatory, deprived of the sacraments – and more. Anyway, this just goes to show that even this ‘authoritative’ ODNB is prone to partiality. The next issue of the Mitre Literary Review will contain a review essay on Michael Wood’s In Search of Shakespeare, which explores the evidence in a popular and well-presented form. St AndrewsIt is pleasing to see that some St. Andrews academics have contributed entries on eminent writers. Professor Nicholas Roe has written on Leigh Hunt, Professor Robert Bartlett on Gerald of Wales and others, Dr Ian Bradley has an entry, as does Professor Trevor Hart, and Professor Robert Crawford has the honour of carrying off Robert Burns, the famous illiterate Scotch poet. However, I was surprised to see that the most prolific (insofar as I can establish) St. Andrean to contribute to the ODNB was Canon Brian M. Halloran, Catholic chaplain and parish priest at St. James’. Canon Halloran contributes seven fine entries. Few will have heard of his subjects, and it is, I think, accurate to say that the field of Scots priests in penal times is what is known as an academic niche. His longest entry regards Bishop George Hay, ‘vicar apostolic of the lowlands district’ in penal times, and makes interesting reading. Hay wrote a number of pious works for the edification of Scots, and, the seminaries at Douai and Paris having collapsed at the French Revolution, established one at Scalan in Glenlivet. However, despite the admirable contribution of Hay to the Catholic Church in Scotland, Canon Halloran points out that he ‘when prejudiced, could be judgemental and even condemn without evidence.’ Halloran, himself a fair-minded man, may surprise many in this town with his erudition. The entries, or heroic lays, of Canon Halloran on Scots priests are in contrast to the scholarly scepticism of Professor Robert Bartlett. A world-renowned mediæval historian, he shows how wrong St. Bede was to believe that there was such a saint as St. Bega, ‘supposedly active in the seventh century’. She became a nun, so the story goes, having pledged her life to celibacy, and a visionary figure gave her an arm-band as a token of her commitment. Bartlett deconstructs this pious tradition. ‘Since Bega’s bracelet was the focus of the Cumbrian cult and the Old English word for ring or bracelet is beag, the suspicion naturally arises that originally St Bega was a bracelet and that the Cumbrian cult started from a holy armband that only gradually metamorphosed into the person, St Bega.’ This is like the higher criticism of the nineteenth century. St. Bega was a bracelet? Sounds a bit Ovidian to me. And she became, what, gradually less like a bracelet and more like a person? I wonder what the odds of that happening are. My theory, and it seems at least equally plausible (though I am utterly ignorant on the matter), is that there was a saint who left a holy bracelet, and after her death her name, perhaps resembling beag, was replaced by the name of the holy object itself. Only problem is this is based on the presumption that we should trust tradition. I was unable to find any other cases in the ODNB of arm-bands becoming saints (or vice versa) – but this doesn’t mean there aren’t any. Professor Bartlett demonstrates his eminence with his fine entry on Gerald of Wales (c.1146-1220), which ends nicely with the observation that Gerald is ‘remembered not as a vain and disgruntled clerical careerist but as a pioneering observer of the Celtic lands and peoples.’ The Last ChurchmanAs has been generally observed, the ODNB is most useful for those figures who have not attracted full-length biographies, and it is on the quality of these that the ODNB must be judged. One such figure is John Carmel Heenan, Archbishop of Westminster from 1963-75, and a cardinal from 1965. Heenan is surely the last great English churchman in the tradition that begins with Wiseman and the restoration of the Catholic hierarchy. Heenan’s experience at the Second Vatican Council (1962-65) was deeply unhappy, though his loyalty to the Church was greater than his personal misgivings (this is reflected in the fascinating letters between Heenan and Evelyn Waugh). According to Michael Gaine, who has written this neat entry, ‘English Catholicism had been ill-prepared for the council, and Heenan was out of tune with the liberal trends in European theology which were its driving force.’ Moreover, ‘he could not accept that the new men at the council, innovators in theology, apologetics, and catechists, were any more apostolic or capable exponents of Catholic doctrine than were their predecessors. At times he felt that they were undermining the faith, and he once launched a famous attack against the theological experts at the council, ‘Timeo peritos et dona ferentes’ (‘I fear experts and those bearing gifts’)’. I wonder whether there is a need for a fuller biography of this great pastoral bishop, who, whilst not being a ‘progressive’, was a great innovator, and was a master first of radio and then television. Oh for another Heenan. Whatever its shortcomings, the ODNB is a treasure-trove of the great, the eccentric, and the obscure. For a sort of lucky dip approach, OUP will send a biography of the day to your email inbox. One feature which people seem to like is the ‘wealth at death’ figure at the end of many biographies. There are also thematic lists of biographies, such as mythical figures and prime ministers. There is also an entry on Jack the Ripper, of whom we know nothing but his crimes. I’ll read that when I’ve got a moment, along with the life of Adrian IV, the English pope.

February 1, 2005 12:35 pm | Link | Comments Off on The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ‘Phoenix’ QueenJohn Guy’s Mary is a phoenix, the mythical bird that rises gloriously from the ashes of its own burning remains. In captivity, ‘In the end is my beginning’ was Mary’s chosen motto, words borrowed from her mother, Mary of Guise, and emblazoned on her cloth of state. The epitaph suits a Queen whose fate was to triumph only in death, as ‘one of the most celebrated and beguiling rulers in the whole of British history.’ In life, however, Mary was ‘the unluckiest ruler in British history’, a victim of ambition, deceit, mistrust and jealousy. And it is this well-worn story, played out once more in the most minute detail, which Guy tells. Mary triumphed in death, and Guy’s sympathetic narrative (he promises to ‘tell Mary’s story … in her own words’) begins with a rather gruesome depiction of her execution. Proudly clad in undergarments of scarlet, the liturgical colour for Roman martyrs, Mary goes to her death dressed as a martyr to her Catholic faith. ‘I am settled’, she said, ‘in the ancient Roman Catholic religion, and mind to spend my blood in defence of it.’ Her crime was treason, plotting to overthrow Elizabeth I and install herself on the English throne, which she and many believed to be rightfully hers, and restoring the Catholic religion, a last act of desperation to end her years of captivity. She had been ‘done over’ so many times that when presented with an opportunity to regain some control she took it desperately. Mary’s Catholicism, however, was only displayed proudly and defiantly once she had lost. As a reigning Queen, she ardently advocated religious toleration (a practicing Catholic, she however, had no qualms about a Protestant marriage ceremony to her third husband, Bothwell) but once captive and desperate she sought help from her foreign Catholic allies such as Philip II of Spain, and wore her Catholicism proudly on her sleeve. She was persecuted because she was Catholic. Guy presents Mary as an extremely engaging, beautiful, intelligent and imposing figure (standing at nearly six feet tall, Mary would often disguise herself as a man so as to enjoy a degree of anonymity). But as a Queen almost from birth, her fate was to be forever a power tool. As a baby she was the subject of Henry VIII’s ‘rough wooings’ – his policy of destruction in Scotland to force a betrothal of Mary to his son, the future Edward VI. As regent, her Mother Mary of Guise, perhaps the only person who truly loved Mary, did all in her power to protect her, eventually sending her to France to live at the French Court, under the protection of the King of France, Henry II. This was perhaps the most peaceful and trouble free time of Mary’s life, culminating in her ‘ideal dynastic marriage’ to the Daupin, Francis at the age of 15. Just over a year later, they were crowned King and Queen of France. But happiness was not to last. Within the year Francis II was dead and Mary, pushed aside by her fearsome Mother-in-law Catherine de Medici, returned to Scotland, at the age of nineteen, to reign as Queen in the land of her birth. And it is here that Guy’s story begins to pick up. Mary’s life in Scotland is the stuff of thrillers and, although heavily weighed down throughout with complicated politicking, at this stage the biography becomes a page-turner, depicting love, betrayal, and murder. Despite Mary’s best efforts to rule and maintain a level of religious toleration, she is thwarted at every opportunity by the ambitious, factionalised Scottish Lords, in particular her half-brother James Stuart, Earl of Moray. It is in keeping up with the ploys and power-plays of these ambitious Lords each wanting a chunky slice of power, that one can lose a grip on the story. The Lords are presented as the enemies of Mary, along with the cruel and ‘indomitable’ John Knox. But the consistent baddie of Guy’s narrative is the shadowy and highly sinister figure of William Cecil, Elizabeth’s chief minister and leading adviser for forty years, who engineered the downfall and disposal of Mary from the time of her coronation as a baby. Guy claims that ‘the collapse of Mary’s rule in Scotland was not an accident’ but had been engineered all along by Cecil. Driven by his ambition to secure the British Isles as a single, Protestant community, in his mind there was room for only one Queen and therefore sought to find and encourage ways of undermining Mary at every turn, encouraging the first revolt against her in 1559-1560 and then standing behind the most troublesome Lords, the Earls Moray, Maitland and Morton. Without his support, their efforts would have been futile. But Guy, ever sympathetic, argues that Mary successfully ‘managed to hold together a divided and fatally unstable country,’ handling people ‘just as masterfully as her English cousin and counterpart.’ If ever there was an issue, however, which Mary wanted settling, it was the question of her dynastic claim to the English throne. As the natural successor to Elizabeth, she, from the time of her return to Scotland as a young woman, longed for a meeting with her ‘own dear sister’, believing her to be her closest ally. Cecil of course dreaded such a meeting; it served his interests to keep the two Queens apart. Elizabeth, for her part merely ‘feared that the younger, possibly more beautiful Queen of Scots was so magnetic, so brilliant in conversation, that she would overshadow or surpass her.’ Where Mary failed, according to Guy, it was in her choice of husband and it was here that her greatest failing, her naïveté and her easy willingness to trust, were exposed. Desperate for someone who would shield her from the feuding Lords, Mary’s greatest error was her second marriage to the narcissistic, ambitious and bisexual Lord Darnley. The marriage plunged her deeper into the power plays of the Lords and when he was ruthlessly assassinated by them, chiefly Bothwell, her demise was secured. History implicated Mary in the plot, arguing that if she wasn’t involved directly, she must have at least known about it. But Guy refuting this argues that she was neither involved nor knew about it and her affair with Bothwell did not begin until after her husband’s death. In allowing herself to be seduced by Bothwell and marrying him, she secured her destiny. Her errors – as with the plot to overthrow Elizabeth – are narrated by Guy as if Mary erred only when driven to desperation. With Darnley, another successor to the English throne, it was desperation over Elizabeth’s refusal to meet her and settle the dynastic claim; with Bothwell, a true affair of the heart she was manipulated by his masculinity and sought his protection from the Lords; and with the disastrous treason plot, a desperate desire to end her years in captivity and to once again be recognised as the Queen she was born to be. My Heart is My Own depicts Mary as a Queen ‘to the last fibre of her body and soul.’ It suggests that she would have reigned successfully if allowed to get on with it. But Elizabeth was jealous of her, Cecil despised her and the despicable Scottish Lords used her for their own ambitious ends. Essentially she was an inconvenience and was killed because of it.

February 1, 2005 12:30 pm | Link | Comments Off on The ‘Phoenix’ Queen

A Little Gem from the Master of the DoorstopIn this short, autobiographical portrait of a childhood in the North Staffordshire town of Turnstall in the ‘Hungry Thirties’, Paul Johnson, Spectator columnist and author of such panoramic tomes as A History of The American People, certainly does conjure up a vanished landscape, and a vanished way of life. In contrast to today’s uniform urban sprawl and the enthralment of much of the population to television, here we encounter the unique jolie laide landscape of the Potteries, with smoke, sparks and flames emanating from the pot-banks (busily baking the famous local wares); a world where children made their own amusement, a car was a rare thing and milk was delivered by pony and trap. Johnson grew up in a middle-class family consisting of mother, father, and elder siblings Tom, Clare and Elfride. Originally they hailed from Manchester, but they moved to Turnstall when Mr Johnson, a sensitive, talented artist, was offered the position of headmaster at the local art school. It was he who taught ‘Little Paul’ to draw and tell the time, and took him to the fascinating pottery factories; but it was his mother who held the biggest influence on the young Johnson. A friendly and funny woman, already forty when she gave birth to him, Mrs Johnson always treated her youngest like an adult, relating the latest stories concerning the locals and her acute observations to him in precise language: ‘it was like being a child of Jane Austen’. She had a powerful memory, reciting swathes of Shakespeare, song lyrics and poetry to her attentive son. His elder sisters also contributed to his care. Nature-mad Clare, who ‘ran up trees like a squirrel’ and budding poet Elfride would often take Johnson on adventures to the local park or nearby countryside, elucidating to him such diverse subjects as cloud formation and Clive of India. Unsurprisingly, when at school (first St Dominic’s, where the nuns smelt headily of ‘soap and linen’, then on to the more austere Christian Brothers) Johnson was a voracious reader, and would be reprimanded for quoting insalubrious chunks of Dickens. Another blossoming passion was history, and by eight he was cycling alone to Chester for the day to look around the roman remains. Detail is not restricted to the Johnson family, with many local characters recalled in delightful details. The two parish priests are especially colourful. Fr Ryan, fierce and demanding, was obsessed with improving his ‘aesthetic mongrel’ of a church (three and a half domes, one Gothic tower), and thought nothing of breaking off mid-Mass and persuading the congregation to trudge round the streets in procession behind the Blessed Sacrament, singing ‘Faith Of Our Fathers’ just to annoy the separated brethren. Meanwhile, young Fr Cocoran, ‘so freckly Gerard Manley-Hopkins could have written a poem to him’, spent his time throwing his shoes at the cats who kept him awake all night with their meowing. By the end of the Thirties, and the book, all this was fast disappearing. Clare and Elfride were off to university; gas masks were being issued; and the toy soldiers Johnson had played with all his boyhood (with figurines of John the Baptist and the actress Fay Wray) were fading into insignificance against the real soldiers he saw on the street. This book is a joy to read, and often amusing. Much comedy comes from his childhood misunderstandings of the English language: thus when the horrid Rena Milton boasts after their First Confession that she admitted nine sins, he is perplexed by Sr Angela’s exclamation that ‘she has broken the Seal of Confession’ because ‘the only seal I could think of balanced a big rubber ball on its nose, or, in the Guinness advertisement, a full pint of stout’. Pen and wash illustrations by the author, liberally sprinkled throughout, give an extra personal touch to what is a delightful memoir. Warmly recommended.

February 1, 2005 12:25 pm | Link | Comments Off on A Little Gem from the Master of the Doorstop

The Caedmon JazzNow we must sing… Yes? All eyes converge on him. Now we must sing of the origin of things It is a beginning, granted, Now we must sing a hymn, praising Him Hild overhears from the cloister He first adorned the earth So, this is how the vernacular sounds

February 1, 2005 12:20 pm | Link | Comments Off on The Caedmon Jazz

Dr. Johnson’s St Andrews LamentSamuel Johnson and his Scotch companion James Boswell embarked for Scotland ‘in the autumn of the year 1773’, and their excursion was written up by Johnson as A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland (1775). This classic travel book contains a fascinating entry for St. Andrews. “St. Andrews seems to be a place eminently adapted to study and education… exposing the minds and manners of young men neither to the levity and dissoluteness of a capital city, nor to the gross luxury of a town of commerce, places naturally unpropitious to learning.”

The Scottish tour provided for Johnson what has been called ‘a realm of experience foreign to the Enlightenment illuminati of London and Edinburgh’. Johnson said simply, ‘I saw a quite different system of life.’ Shades of the Scottish past darkened in distinct bands as Johnson and Boswell journeyed north – beyond Inverness was ‘a much harsher world’, which manifested itself both in difficulty of travel and in the destruction wrought by the Highland clearances, which had swept away the ancient Gaelic speaking culture that had existed from the Highlands to the Islands of Scotland. But Johnson began his tour in the civic Scotland of the east coast, passing from Edinburgh to St. Andrews, and then to Aberdeen. If the northern regions revealed a half-forgotten Gaelic past, St. Andrews was a relic of Catholic Scotland, formerly pious, learned, and grandiose. Johnson found a cathedral ruined, locals carrying away its stone for their own houses, the whole site cluttered with rubbish, and a mad old woman living in a hole – but he saw beyond its decay and demise, that it had been once ‘a spacious and majestick building, not unsuitable to the primacy of the kingdom.’ Boswell recorded that “Dr Johnson’s veneration for the Hierarchy is well known. There is no wonder then, that he was affected with a strong indignation, while he beheld the ruins of religious magnificence. I happened to ask where John Knox was buried. Dr Johnson burst out, ‘I hope in the high-way. I have been looking at his reformations.’”

The university itself was in a parlous condition, entering its eighteenth century slump. Neither flourishing nor utterly ruined (as were the churches), Johnson saw the university ‘pining in decay and struggling for life’. As for numbers, against our six thousand, at the time of Johnson’s visit there were one hundred students – St. Mary’s divinity faculty capable, but not holding, fifty; and fees were £10 for poorer students. Though Johnson considered the town ‘a place eminently adapted to study and education’ still a sense of unease remained in his memory after the visit’s accidental pleasantries – he notes excellent hospitality – had been enjoyed. What are today admired as romantic ruins – the cathedral, the castle, St. Mary on the Rock –, Johnson saw, with greater insight, as ‘mournful monuments’ to a lost civilisation. (Incidentally, the one really impressive remain, St. Rule’s Tower, they completely overlooked.) Dr. Johnson concludes summarily: ‘The kindness of the professors did not contribute to abate the uneasy remembrance of an university declining, a college [St. Leonard’s] alienated, and a church profaned and hastening to the ground.’

February 1, 2005 12:15 pm | Link | Comments Off on Dr. Johnson’s St Andrews Lament

The Meaning of ‘Aardvark’

There was no comprehensive dictionary in the language, – only one by Nathan Bailey in 1721 which pathetically defined a mouse as ‘an animal well known’, revised after complaint to ‘a small Creature infesting houses’. Something more satisfactory was needed, and the task – proposed previously to Addison and then Pope – fell to Johnson, who in 1755, after nine years, produced a dictionary of 40,000 words, advertising itself ‘etymological, analogical, syntactical, explanatory and critical’. He would define mouse as ‘the smallest of all beasts; a little animal haunting houses and corn fields, destroyed by cats.’ Much better. Though 40,000 words is a fraction of the OED and indeed even less than Bailey’s earlier dictionary, Johnson’s word-hoard was far beyond a mere improvement. It was a giant leap in classification, schematically distinguishing between the senses of every word. Being a masterpiece of English prose, with definitions so pithy and correct that many are borrowed still by modern lexicographers (def. ‘a writer of dictionaries; a harmless drudge’), it remained the standard well into the nineteenth century. Only the philology of that century – which showed many of Johnson’s etymologies to have been fanciful – enabled the creation of a dictionary that surpassed it. The work was a triumph of scholarship, though admittedly with ‘a few wild blunders and risible absurdities’ (corrected in the 2nd edn.). It earned him the nickname ‘Dictionary’ Johnson, and the reputation as England’s foremost man of letters, living outside the universities and surviving on commercial success rather than a fellowship. However, the adulation was not universal. The dictionary did not go down well in Scotland, and a St. Andrews theologian and classicist called Archibald Campbell attacked ‘our English Lexiphanes, the Rambler’, ‘the great corrupter of our taste of language’, and his personal, political, and national dictionary. But this was in its way a tribute, for the Dictionary was a personal work – not the product of an institution, as were the 1612 Vocabolario of the Academia della Crusca, or the 1694 Dictionnaire of the Académie française. Johnson’s Dictionary of 1755 was the work of an individual animus and it shewed forth the man. The dictionary is famous for its succinct definitions and array of quotation, the latter chosen judiciously to illustrate the former. In search of exemplary usage, Johnson borrowed and defaced his friends’ books, and proclaimed that he had ‘extracted from his philosophers principles of science; from historians remarkable facts; from chemists complete processes; from divines striking exhortations; and from poets beautiful descriptions’. The result was that those authors selected as exemplary became with Johnson ‘authorities’ (the dictionary was an important step in canon-formation), and their example, for good or ill, standardised ‘good’ English usage. This act of codification made English a bit more like Latin and Greek, and a bit less wild and organic. Johnson was, however, criticised for airing his prejudices in a work of supposed scholarship, as when he famously defined Whig, ‘the name of a faction’, in contrast to Tory, ‘One who adheres to the ancient constitution of the state, and the apostolical hierarchy of the church of England, opposed to a Whig’. An innocuous word like oats became an opportunity to needle the Scots (especially Archibald Campbell), which he took up willingly: ‘oats. A grain which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people.’ Besides such cameos, the dictionary shows the prejudice of its age by ignoring mediæval literature in its quotations. ‘I have fixed Sidney’s work for the boundary beyond which I make few excursions’, wrote Johnson is his Preface. Shakespeare got in, as furnishing ‘the diction of common life’, but Johnson thought the English language was shown in its purity in Hooker, the King James Bible, Bacon, Raleigh, Sidney, and Spenser (all canonical works of early English Protestantism). Johnson’s authorities were post-mediæval but pre-Restoration. Quoting Spenser, he called them ‘the wells of England undefiled, … the sources of genuine diction.’ Pre-sixteenth century texts did admittedly lay largely unedited, in dispersed (if not destroyed) monastic libraries and great private collections, but still his canonical dictionary cut England yet further adrift from its mediæval heritage. Such a literary approach, basing English usage on great writers, differs from the practice of Johnson’s modern OED successors, but Johnson thought the lexicographer’s role was not to reflect common usage but to ‘correct or proscribe’ where he found linguistic ‘improprieties and absurdities’. As he explains in his fine Preface, he was not seeking to record the language but to improve it. Curiously, Johnson cited ‘no author whose writings had a tendency to hurt sound religion and morality’, and famously when congratulated by some ladies on excluding all the ‘naughty’ words, replied unsparingly, ‘What, my dears, then you have been looking for them?’ It has been pointed out to me that the ladies either did not find, or did not consider sufficiently naughty, the entries for ‘piss’ and ‘fart’. Consistent with his method of definition followed by illustration, the latter was accompanied by a quotation from Swift:

But for many the relative conservativism of the dictionary was not a virtue, and so as a symbol of her rebelliousness Becky Sharpe tosses a copy from her carriage at the beginning of Vanity Fair. I encourage all to take a brief look at the fine facsimile of the 1755 first edition, in two enormous volumes in the dictionary section of the University Library. The modern reader can certainly still enjoy Johnson’s magnum opus, though some definitions are abstruse, such as, notoriously, ‘Net: Anything reticulated or decussated at equal distances, with interstices between the intersections.’ As his biographer Boswell comments, critics found this guilty of ‘obscuring a thing in itself very plain.’

February 1, 2005 12:10 pm | Link | Comments Off on The Meaning of ‘Aardvark’

All That is Seen and UnseenDame Muriel herself is the major obstacle to reading her work. It is difficult not to become emotionally involved in the author, either with her narratorial voice, or with semi-autobiographical characters which portray Spark at various points in her life. The moral fluidity of Fleur Talbot in Loitering With Intent can depress a reader, especially a male one, into hating the character and, by extension, the author, with disastrous consequences if one wishes to continue reading her work. The feeling with Fleur when she justifies adultery or theft is like that of a child discovering that their parents or priest are imperfect. Spark is very much a deity in the world of her novels. Having said this, Dame Muriel’s novels are so rich and deep with the highs and lows of humanity that one must be brave if one is to experience the works of a lady who, I am convinced, will be seen as one of the great English language prose writers of the twentieth century. Dame Muriel was born in Edinburgh of a Jewish father and Presbyterian mother, attended a Church of Scotland (hurrah!) school, and became a Roman Catholic. She lived in Edinburgh, Rhodesia, London, and now Tuscany. She has been a poet, editor, mother, and a second world war intelligence officer. All this is encapsulated in her novels. Yet she is not an author who needs to pander to contemporary literary needs (rough sex, heroine spikes, poverty). She writes what she knows in a style which feels timeless. It is sometimes jarring to hear her describe the internet, for example. Indeed it is important to note that she started writing novels in 1958 when she was thirty-nine. Having lived through a failed marriage, childbirth, war, a mental breakdown, a conversion through the works of Cardinal Newman to Roman Catholicism, she was in a position to write novels of experience and authority, as well as a tender beauty, born out of suffering. She is still writing. To be some help to the reader who is interested in Spark’s novels, I will suggest three very different novels of hers to start on, according to taste, none of which are The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, classic though it is: The Public Image is one of Spark’s darker novels, curiously foreshadowing the explosion is the cult of the celebrity and the paparazzi phenomenon. Annabel Christopher is the latest hot British film star, with a writer husband and a head for PR. She cannot act. Yet Spark seems sympathetic to her major talent: she is the English tiger-lady, very much like Rosamund Pike’s role in “Die Another Day”. She is the beautiful, cultivated English mother, sophisticated and proper. Yet behind her wide eyes and away from the cameras she is an insatiable tiger in the bedroom. In real life Annabel Christopher is a pretty girl who got lucky and has very little time for sex, let alone insatiable tiger sex. The sympathy comes from her portrayal as a male fantasy. Her ruthless calculations in dealing with her husband’s suicide reveal her real inner strength. Although definitely not a feminist, Spark here creates a novel which is very scathing in its social implications, yet gripping and readable as any popular novel. For a lighter read, try Aiding and Abetting. This 2000 novel deals with Lord Lucan, supposing that he is still alive and seeking therapy. Except that in Spark’s world, there are two Lucans, each trying to prove that they are genuine. The therapist herself is a fake stigmatic, who made a fortune fooling the masses, and now has her own disturbing method of psychoanalysis. Much is made of Spark as a Catholic novelist, yet I think that this is a part of her work as much as any other part of her life is part of her work. Her perspective on the Church of Rome is, however, very interesting and is certainly something to think about when reading her novels. Aiding and Abetting has many examples of Spark giving clues to the reader, only to take the solution away from them until she feels that she should reveal it. It is this teasing aspect to her novels which is so seductive. One can read this as a top quality detective novel. Finally, I would suggest reading The Girls of Slender Means. Set in a second world war hostel for young ladies, Dame Muriel creates a novel which reflects humanity through the lens of these young girls working in London. Nicholas Farringdon has ambitions to explore the girls intimately, and ends of making them his idealised conception of society. His is trying to write a philosophical treatise among the chattering of debutantes and secretaries. This novel does contain examples of Spark’s wicked and wonderful humour, she as the chatter of the upper-class Dorothy Markham: ‘He actually raped her, she was amazed… Filthy luck, I’m preggers. Come to the wedding!’. There is always an ironic edge to Spark’s work, which will frequently have one laughing out loud. I do hope you will begin to read the novels of Dame Muriel Spark as they are such a treasure to the English language that it is sad to think of them languishing on bookshelves in need of a good home. There is always more to her than meets the eye.

February 1, 2005 12:05 pm | Link | Comments Off on All That is Seen and Unseen

Leisure, the Basis of CultureIn Defence of Time-WastingTo read a literary journal requires leisure; and to be reading this new literary journal suggests an excess of it. Moralists and even some parents will stress that we must make good ‘use’ of our university years. But this word has mildly pernicious connotations of usefulness, and by extension utility, and a humanities degree should be, to all intents and purposes, useless. Those who study English literature for employment reasons are corrupting the system of education. (This is not to say one should not seek employment after one’s degree.) Time-wasting it may be, but the intellectual life is, in its fullness, a sort of consecrated time-wasting. It is good for the soul. In repudiating the language and ethos of the modern Total Work State, the intellectual, with his celebration of time-wasting, may seem to speak with unbecoming levity. The intellectual prides himself in being utterly non-utilitarian, and therefore he appears to the ‘real world’ as sort of heretic. He has opted out of the system. Because he does not produce anything marketable, and because his hours are spent in leisure, he cannot even receive a wage. (See Pieper’s Leisure, the Basis of Culture for all this in a much richer form.) For one receives a wage as a bribe – spend your time doing this undesirable job, says the employer, and I shall compensate you £x. But the intellectual is not working, and so cannot be paid except in the form of a donation, grant, or fellowship. Disappearance of the Literary MagazineThe whole movement of the post-war years has been to drive out leisure from society and even from the sanctuary of the intellectual, the academic school. Nowadays, an academic is a member of ‘staff’ in a ‘department’, his or her life is driven by government targets for research not teaching, and the bureaucracy is like that of any other profession. Those in the ‘real world’ say, well that’s life. Indeed it is. But to apply the ethos of the factory or office to the academic school impoverishes it, and the form-filling activities which are common to many jobs is less tolerable in academia because ‘wages’ are so low. For wages must be paid to academics, now that they are workers. Connected to this deprivation of leisure is the disappearance of the literary magazine. The corollary of research-based departments is a low amount of class hours and so at least while academics have no time for such things as journals, the students do (though in practice there are few such ventures). The classical literary magazine, popular outside the academic circles, which flourished for two-and-a-half centuries until the second war, is now not only dead, but forgotten. Again, this is explained by the all-subsuming Total Work State which sucks the leisure out of our lives. What was noble in working-class culture – Ruskinian evening lectures, a respect for education, that sort of thing – has been assuredly undermined by commerce driven popular culture. Home from the factory or office to slump at home and then out for another day ad infinitum. That is exactly what the government wants – unskilled labour with no aspirations. And then there is the other thing much desired – the continuing decline of religious belief, for religion is the thing most likely to bring lofty ideas about human dignity to the proles. It’s fairly obvious that Matthew Arnold’s naïve faith in the ability of culture (without religion) to circulate ‘the best that has been thought and known in the world’ has been proven nonsense. Addison and SteeleIf we are to have a literary journal then, let it be one based on leisure. It is unlikely that much will be learned from the Times Literary Supplement and the London Review of Books, though both are superb in their way. But much will be learned from the eighteenth century prose-stylists, like Addison and Steele who produced the Tatler and the Spectator. Their great literary essays combined the ‘novelty of literary experiment with the security of journalistic convenience’. In that tradition are all the popular journalists up to Chesterton. The Spectator was the conversation, quite literally, of the coffeehouses of London; it was the product of leisure. And so Addison’s creature, the Spectator, famously proclaimed that ‘I have brought philosophy out of closets and libraries, schools and colleges, to dwell in clubs and assemblies, at tea tables and in coffeehouses.’ It makes sense that the writers who produced the great essays are not on our university syllabi. According to one honest left-wing critic, ‘[t]he work of both Addison and Steele has features that render it useless to critics housed in English departments.’ The occasional essay is an inherently ‘conservative’ form, embodying the high-leisure of the bourgeoisie; its subjects are often directly related to leisure, such as Chesterton’s gem, ‘On Lying in Bed’. As such, what use has this form for the modern academic department? Anyway, before your editor gets too heated and emotional, let us conclude by saying that the Mitre Literary Review, the little brother of the Mitre, is a minor show of defiance. The journal has no ‘learning outcomes’ and we hope you catch no ‘transferable skills’. We aspire, at least, to read and write for no end other than to make edifying use of our leisure time. We hope you consider our Review, as one critic called the original Spectator, ‘a wholesome and pleasant regimen’.

February 1, 2005 12:00 pm | Link | Comments Off on Leisure, the Basis of Culture

|

Robert O'Brien Editor Matt Bell Associate Editor Andrew Cusack Publisher Founded in 2005 at the University of St Andrews in Scotland |