Vatican

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Special Mission to Rome

RELATIONS BETWEEN THE Court of St James’s and the Holy See have evolved in the many centuries since the Henrician usurpation. At times, such as during the Napoleonic unpleasantness, the interests of London and the Vatican were very closely aligned — despite the lack of full formal diplomatic relations. Later in the nineteenth century Lord Odo Russell was assigned to the British legation in Florence but resided at Rome as an unofficial envoy to the Pope.

It wasn’t until 1914 that the United Kingdom sent a formal mission to the Vatican, but this was a unique and un-reciprocated diplomatic endeavour — a full exchange of ambassadors would have to wait until 1982. (Until then, the Pope was represented in London only by an apostolic delegate to the country’s Catholic hierarchy rather than any representative to the Crown and its Government.)

Within a year of the Special Mission to Rome being established, John Duncan Gregory (later appointed CB and CMG) was assigned to it. A diplomat since 1902 who had previously worked in Vienna and Bucharest, he was one of the central figures in the curious ‘Francs Affair’ of 1928, when two British diplomats were believed to have unduly abused their positions to speculate in currency. Despite being cleared of illegality, J.D. Gregory was dismissed from his diplomatic posting — though he was later rehabilitated.

Within a year of the Special Mission to Rome being established, John Duncan Gregory (later appointed CB and CMG) was assigned to it. A diplomat since 1902 who had previously worked in Vienna and Bucharest, he was one of the central figures in the curious ‘Francs Affair’ of 1928, when two British diplomats were believed to have unduly abused their positions to speculate in currency. Despite being cleared of illegality, J.D. Gregory was dismissed from his diplomatic posting — though he was later rehabilitated.

If there are any enthusiasts of the curious subcategory of accoutrement known as the despatch box, J.D. Gregory’s one dating from his time in Rome is currently up for sale from the antiques dealer Gerald Mathias.

It was manufactured by John Peck & Son of Nelson Square, Blackfriars, Southwark — not very far at all from me as it happens. (more…)

Romes that Never Were

When the splendidly named Saint Sturm – Sturmi to his friends, apparently – founded the Benedictine monastery of Fulda in A.D. 742 we can presume he had no idea that the magnificent church eventually erected there (above) would one day be considered for housing the Supreme Pontiff of the Universal Church.

Rome, caput mundi, is ubiquitously acknowledged by all Christian folk as the divinely ordained location for the Papacy, but this has not always been acknowledged in practice. Most memorable is the “Babylonian Captivity” of the fourteenth century when the papal court was based at the enclave of Avignon surrounded by the Kingdom of Arles. The illustrious St Catherine of Siena was influential in bringing that to an end.

Since the return from Avignon the Successor of Peter has prudently been keen to stay in Rome, but various crises over the past two centuries have seen His Holiness shifted about. General Buonaparte successively imprisoned Pius VI and Pius VII while he made to refashion Europe in his likeness, and the later slow-boil conquest of the Italian peninsula by the Kingdom of Sardinia caused much worrying in the courts of the continents as well.

In 1870, the Eternal City fell to the troops of General Cadorna, and while the Vatican itself was not violated it was widely assumed the papacy could not stay in Rome. Pope Pius IX evaluated several options, one of them seeking refuge from – of all people – the Prussian king and soon-to-be German emperor Wilhelm I.

Bismarck, no ally of the Church, but shrewd as ever, was in favour of it:

I have no objection to it — Cologne or Fulda. It would be passing strange, but after all not so inexplicable, and it would be very useful to us to be recognised by Catholics as what we really are, that is to say, the sole power now existing that is capable of protecting the head of their Church. …

But the King [Wilhelm I] will not consent. He is terribly afraid. He thinks all Prussia would be perverted and he himself would be obliged to become a Catholic. I told him, however, that if the Pope begged for asylum he could not refuse it. He would have to grant it as ruler of ten million Catholic subjects who would desire to see the head of their Church protected. …

Rumours have already been circulated on various occasions to the effect that the Pope intends to leave Rome. According to the latest of these the Council, which was adjourned in the summer, will be reopened at another place, some persons mentioning Malta and others Trent.

Bismarck mused to Moritz Busch what a comedy it would be to see the Pope and Cardinals migrate to Fulda, but also reported the King did not share his sense of humour on the subject. The advantages to Prussia were plain: the ultramontanes within their territories and throughout the German states would be tamed and their own (Catholic) Centre party would have to come on to the government’s side.

In the end, of course, the Pope decided to stay put in Rome and became the “Prisoner of the Vatican”, surrounded by an awkward usurper state that made attempts at friendship without betraying its hopes for legitimising its theft of the Papal States. It was the diplomatic coup of the Lateran Treaty in 1929 that finally allowed both states to breathe easy and created the State of the City of the Vatican, an entity distinct from but subservient to the Holy See of Rome.

The Second World War brought its own threats to the Pope’s sovereignty, and the wise and cautious Pius XII feared he might be imprisoned by Hitler just as his predecessor and namesake had been by Buonaparte. Pius was determined the Germans would not get their hands on the Pope and so signed an instrument of abdication effective the moment the Germans took him captive. He would have burnt his white clothing to emphasise that he was no longer the Bishop of Rome.

The record is not yet firmly established but it is rumoured that the College of Cardinals was to be convened in neutral Éire to elect a successor. One wonders where they would have met. The Irish government would undoubtedly have put something at their disposal — Dublin Castle perhaps? Despite the whirlwind of war, the election of a pope in St Patrick’s Hall would have warmed the cockles of many Irish hearts.

But what then? Ireland’s neutrality would have been useful but a German violation of the Vatican’s territory would have been grounds for open, though obviously not military, conflict. Further rumours, also totally unsubstantiated, had it that the King of Canada, George VI, quietly had plans drawn up for offering the Citadelle of Quebec to the Pope to function as a Vatican-in-Exile. Others claim it wasn’t until the 1950s that Quebec was investigated as a possibility by the Vatican in case Italy went communist, as was conceivable.

So Cologne, Fulda, Malta, Trent? None of these plans ever occurred, thank God.

And what about England? Why not? The court of St James and the Holy See, despite obvious and significant differences, enjoyed close relations and overlapping interests in many particular circumstances from the Napoleonic wars until present. Pius IX had put feelers out to Queen Victoria’s minister in Rome, Lord Odo Russell, in 1870 but the British ambassador more or less told him of course the Pope would be welcomed in England but don’t be silly, the Sardinians would never conquer Rome.

One imagines the British sovereign would grant a palace of sufficient grandeur to the exiled Pontiff. Hampton Court would do the job. It’s far enough from the centre of London but large enough to house a small court and the emergency-time administration of the Holy Roman Church. Would the ghost of Cardinal Wolsey plague the Princes of the Church?

Thanks be to God, we’ve never had cause to find out. At Rome sits the See Peter founded and so it looks to remain. Ubi Petrus, ibi ecclesia.

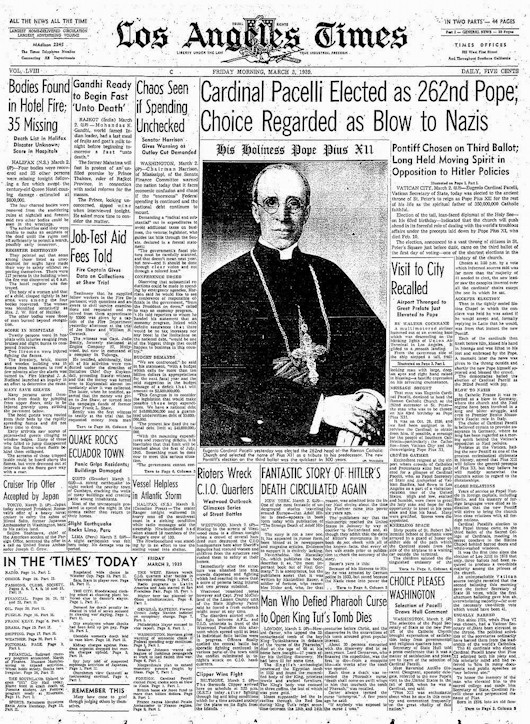

The L.A. Times on Papa Pacelli

How News of the Election of Pius XII was Received in 1939

The case against Pope Pius XII, accusing him of complicity in the crimes of Nazism, has been so thoroughly debunked — by Jews like Gary Krupp and Rabbi Dalin more than any — that it is no longer even worth refuting.

Still, it’s interesting to read the Los Angeles Times’s coverage of his election as Supreme Pontiff in the difficult year of 1939:

BLOW TO NAZIS

… The choice of Cardinal Pacelli is believed certain to provoke annoyance in Germany, where he long has been regarded as a moving spirit behind the Vatican’s opposition to Nazi policies.

As the news report goes on to note, Cardinal Pacelli was elected in only three ballots — the quickest papal election since that of Leo XIII in 1878.

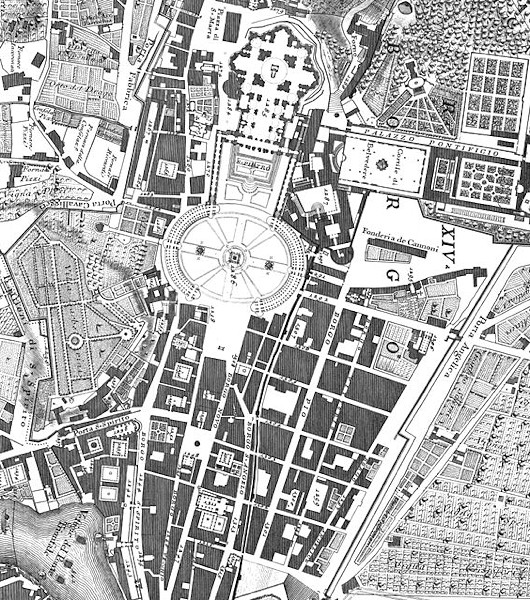

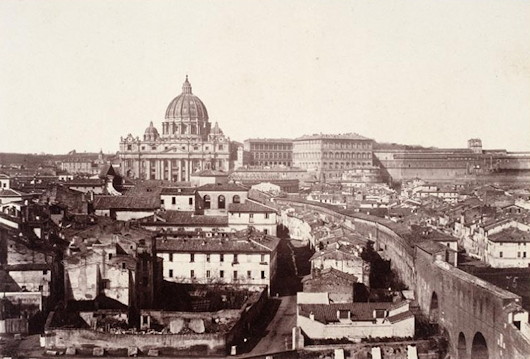

The Spina di Borgo

The Baroque is a style of joy. It is often hailed (or derided) as the most Catholic of styles and in some sense this is true. The festivity and physicality of the Baroque reflect the God that Catholics worship — “the Love that moves the Sun and other stars” as Dante put it — but a Love made incarnate, made man, in a very real and tangible world.

The Baroque is also the style of the surprise: the corner turned to an unexpected vista or the jet of water sprinkling a king’s unsuspecting courtier.

One of the most superb examples of this was the great basilica church of Saint Peter in Rome where prince, pilgrim, and pauper alike moved in a dark warren of palaces, hovels, churches, and alleyways, perhaps catching an occasional glimpse of the great dome looming as they closed in on San Pietro, finally to emerge from the shadow into the great light of the piazza.

That warren of buildings was the Spina di Borgo (“Spine of the Borgo”) but this experience is now sadly lost to us since the 1930s when the Kingdom of Italy’s fascist premier Benito Mussolini decided to raze the neighbourhood. Instead we now have the long boulevard called the Via della Conciliazione, named in commemoration of the Lateran Treaty establishing formal relations between the Holy See and the Italian state.

While Il Duce ostentatiously took credit for this urban crime by symbolically swinging the pickaxe beginning demolition, the concept, though flawed, was in fact an old one. Leon Battista Alberti submitted proposals during the reign of Pope Nicholas V (mid fifteenth century), and numerous other architects — Carlo Fontana, Giovanni Battista Nolli, Cosimo Morelli — drew up similar plans. The Piazza San Pietro only took its now instantly recognisable form in the 1650s when the curved flanking collonades enclosed the space like great welcoming arms superbly framing the basilica’s façade.

Mussolini turned to Marcello Piacentini — an accomplished if sometimes uneven architect — assisted by Attilio Spaccarelli. Piacentini favoured closing off the view from the avenue with a closed collonade, echoing Bernini’s own plans for the piazza, but was overruled.

The razing of the Spina presented a problem in that the undemolished buildings left flanking the Via della Conciliazione were now mostly at odd angles to the new boulevard. Piacentini attempted to solve this by flanking the road with two rows of obelisks that doubled as streetlamps providing a line directing the viewer towards the great basilica beyond, otherwise unimpeded by any visual interruption.

Overall the construction of the Via leaves a rather boring and clinical feeling. The charm and chaos of the Spina has been replaced by a clean and dull boulevard, useful for little more than traffic efficiency and crowd control. The loss of the Spina di Borgo is mourned.

No ‘Malvinas’ Here

Some difficulties of Latin place names in 1930s cartography

It’s no great secret I’m a lover of maps. When calling in to the Secretariat of State on the terza loggia of the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican the other day, I was very pleased to see the cartographic murals there, including the two hemispheres done by Ignazio Danti in the 1580s. Moving to the next interior offices, however, the visitor is greeted by a much more recent mappa mundi, dating from the 1930s, replete with the glamour of empire’s heydey. (more…)

L’Osservatore Romano goes Hungarian

Magyarophiles will be pleased to learn that L’Osservatore Romano, the Vatican newspaper, will begin appearing in Hungarian. The new edition will appear every other week as a four-page insert into Új Ember, the Hungarian Catholic weekly founded in 1945. “We are a small editorial staff,” Balázs Rátkai, editor-in-chief of the weekly, told L’Osservatore.

“However, our intention is to probe and to make our readers think. The collaboration with the Vatican daily is of historic importance for the life of the weekly and of the entire local Church; it not only brings the Universal Church and the Pope closer to us; it will also enrich readers, and through them all of Hungarian society, with new thoughts, opinions and answers.”

Printed as a daily broadsheet in Italian, the Vatican newspaper also has weekly tabloid editions in French, Spanish, English, German, and Portuguese, as well as a monthly version in Polish.

Better late than never

Old hat already, but following the announcement of Benedict XVI’s abdication, the Los Angeles Times solicited opinions from eleven American Catholics — among them your humble & obedient scribe — what they would like to see in the new pope.

I posted in on Twitter, but in case you didn’t catch it there, you can find my contributions (in addition to those of the ten others) at this link. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Waarburg October 2, 2024

- A Prize for the General September 23, 2024

- Articles of Note: 17 September 2024 September 17, 2024

- Equality September 16, 2024

- Rough Notes of Kinderhook September 13, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories