Tradition

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Bertie Monument Unveiled in Malta

During Fra’ Andrew Bertie’s reign as Guardian of the Poor of Jesus Christ, the “of Malta” at the end of “the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem of Rhodes and of Malta” was not a mere historical anachronism. The Prince & Grand Master had a house in Malta where he attended to his cultivation of oranges (the old Grand Master’s Palace in Valetta is now the Presidential Palace of the Maltese Republic). “A friend of Malta,” a recent statement from the Maltese knights of the Order states of Fra’ Andrew Bertie, “his love for Malta and the Maltese peoples’ affection for him originated the inspiration to this wonderful project, to erect a befitting marble lapidary in his memory.” This summer Fra’ Matthew Festing, successor to Fra’ Andrew as head of the Order of Malta, travelled to the Mediterranean island to unveil the Bertie Monument at Casa Lanfreducci, the Order’s Maltese seat. (more…)

Notes of the Netherlandic Church

Willem Jacobus Eijk, Primate of the Netherlands

THE ANCIENT FORM of the Roman rite has returned to weekly use in Utrecht, the primatial see of the Netherlands. Under the guidance of Wim Eijk, Archbishop of Utrecht, the Church of St. Willibrord has introduced a weekly Tridentine liturgy each Sunday at 5:30 pm, to complement the 10:30 am Mass in Latin in the Ordinary Form. (Previously the old rite was offered only once monthly). The Extraordinary Form will be offered by Fr. A. Komorowski & Fr. M. Kromann Knudsen, both of the Priestly Fraternity of Saint Peter (FSSP, or Priesterbroederschap Sint Petrus in Dutch). St. Willibrord’s is a brilliant example of the nineteenth-century revival of gothic architecture, and the concurrent revival of Dutch Catholicism. Yet the parish was also emblematic of the Dutch church’s implosion in the 1960s & 70s. This beautiful, polychromatic monument to God was deconsecrated in 1967, and the diocese planned on demolishing the building. It was later sold, however, and occupied by an Assumptionist priest who continued saying the older form of mass. Joseph Luns, sometime NATO secretary-general and Dutch foreign minister, was a supporter of the apostolate at St. Willibrord’s.

The recently installed archbishop was keen to regularize the former parish’s situation, and erected it as a non-territorial parish under the auspices of the Vereniging voor Latijnse Liturgie (Association for Latin Liturgy) which promotes Latin in both the ordinary & extraordinary forms of the liturgy. The parish newsletter now proclaims that, at St. Willibrord’s, “all masses are once again celebrated ‘ad orientem'”, and both Sunday masses are accompanied by Gregorian chant. The church also revived, starting in 2002, the Procession of the Relics of St. Willibrord, which is held during the annual festival that opens the cultural season in Utrecht, in order to expose the tradition to a wider audience. (more…)

The Church of Howard Johnson

Leve de Koningin!

“Hoera! Hoera! Hoera!” — The Third Tuesday in September Beholds the State Opening of the States-General of the Netherlands

Previously: Prinsjesdag

Reclaiming his Birthright

Blessed Emperor Charles’s two homecomings to Hungary after the overthrow of the Hapsburgs are worthy of the greatest spy novels, except they are fact: the hushed secrecy and underground preparations, the airplane contracted under a false name, the disguises used to sneak over borders. In his first attempt, Charles — the Apostolic King of Hungary — made it all the way to Budapest, only to be persuaded to return to exile by the self-appointed regent, Admiral Horthy (a naval commander in what, by then, was a land-locked country).

The King’s second attempt to reclaim his power was much more considered and deliberate, and he spent some time securing a loyal power base of local nobility before pressing on to Budapest by armoured railway train. The King’s force made it to just outside of the Hungarian capital before they were overwhelmed by troops loyal to Horthy — who, in order to maintain their loyalty, neglected to inform the soldiers and officers that the “rebels” they were fighting were actually those of their King and Queen.

Along his path to the capital, the King was greeted by fervent crowds, and stopped at least twice to review small detachments of troops and to show himself in person to his loyal Hungarian subjects. The King had returned, but sadly not for long. After the failure of this second attempt, the Allied powers refused to allow the Imperial & Royal family to remain in mainland Europe, and exiled them to the Portuguese island of Madeira, where the Emperor-King grew ill and eventually died. He is entombed on the island today — a source of great pride, I am told, to the Madeirans.

Elsewhere: Miracle Attributed to Blessed Charles (Norumbega)

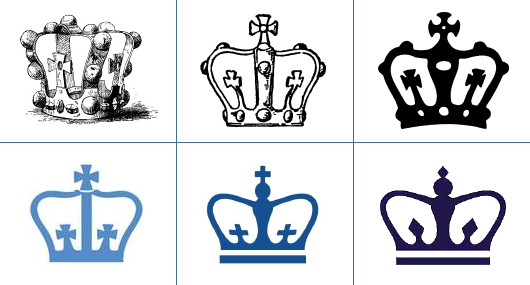

Crosses Return to Columbia Crown

AFTER AN ABSENCE of some years, Columbia University has returned the crosses to its official crown emblem. The crosses had been missing since March 2004, when they were replaced with trapezoidal lozenges, but the more historic cross design has quietly returned to favour as the Ivy League institution’s official symbol. Columbia was founded in 1784, but claims the earlier heritage of King’s College, founded in 1754 but exiled to Nova Scotia, where it now has university status, after the tumult of the American Revolution. A copper crown (right) was originally attached to the cupola of College Hall, King’s College’s home in the colonial city of New York. When Columbia was founded in 1784, a year after New York’s independence was recognized, the state legislature gave the property and endowment of King’s College to the new Columbia College, which was organized by the remaining non-Loyalist members of King’s College. (more…)

AFTER AN ABSENCE of some years, Columbia University has returned the crosses to its official crown emblem. The crosses had been missing since March 2004, when they were replaced with trapezoidal lozenges, but the more historic cross design has quietly returned to favour as the Ivy League institution’s official symbol. Columbia was founded in 1784, but claims the earlier heritage of King’s College, founded in 1754 but exiled to Nova Scotia, where it now has university status, after the tumult of the American Revolution. A copper crown (right) was originally attached to the cupola of College Hall, King’s College’s home in the colonial city of New York. When Columbia was founded in 1784, a year after New York’s independence was recognized, the state legislature gave the property and endowment of King’s College to the new Columbia College, which was organized by the remaining non-Loyalist members of King’s College. (more…)

Wisconsin Baroque, Priests, and Paper Architecture

Matthew G. Alderman

Taken from: Dappled Things, Ss. Peter & Paul, 2009

MY FAVORITE BUILDINGS never got around to being built. Some, like Sir Edwin Lutyen’s majestic design for Liverpool Cathedral, fell victim to budget cuts and the vagaries of history. Others were consigned by good taste, or occasionally outright timidity, to competition honorable mentions, and still others, like numerous student proposals or visionary dreams—like Boulée’s alarming hemispherical cenotaph for Newton, or an imaginary papal palace in Jerusalem cooked up by one of the votaries of the Vienna Sezession—weren’t terribly serious to begin with, unfortunately.

Note that I say favorite buildings, my own personal favorites, rather than the best or the most beautiful. Lutyens’ and Boulée’s fantasies may cross into that sublime territory of beauty by the power of their imaginative vision, but so many of the others owe their charm to their dreamlike extravagances, their intriguing if perhaps incomplete answers. An architect’s education lies in gathering up such fragmentary answers for the questions he will face down the road from clients and patrons. And therein lies the lure, and the value, of paper architecture.

I, like most of my colleagues, spent much of my time in school devising such useful fantasies, sometimes grand, sometimes small. Yet, they were not castles in the air. Each, while often existing in something like the best of all possible worlds in terms of budget and client, was grounded by an actual site and the laws of nature.

The most elaborate of all was my thesis project. It was an imaginary American seminary for a very real religious order, the fast-growing Institute of Christ the King, Sovereign Priest. This new congregation, dedicated to evangelization through the beauty of art, music, and the traditional Latin Mass, started out in, of all places, Gabon in Africa, but its present headquarters lies in Tuscany, in a villa bursting at the seams with seminarians in formation. While their ranks are dominated by Germans and Frenchmen, the increasing number of American clergy and their recent erection of a number of apostolates scattered across the Midwest suggested that a seminary in the United States, if not planned, might at least make for a plausible student project. Also, they seemed to have adventurous taste. I have since developed a passion for the Gothic but my first love has always been the Italian baroque. Perhaps they might be open to its vigorous beauty.

I garnered an award for the end result, the Rambusch Prize for Religious Architecture, and my putative patrons wanted copies of my enormous presentation watercolors to hang on their office walls—though, of course, the seminary would forever remain unbuilt. Its gigantic scale—typical for a student project—put it outside budgetary reach, unless, as someone cheerfully quipped, Bill Gates converted. Yet, the design was logical, consistent, and helped hone design skills I use every day at my drafting board.

The notion for the seminary came shortly after my first real-life encounter with the Institute’s work. My friends and I were road-tripping through the hill country of central Wisconsin, thick with vivid fall colors, and had just come back from a serene, silent low Mass and a long, talkative, private tour of St. Mary’s Oratory in Wausau. The Institute had transformed from a bland Midwestern Gothic to a dazzling near-replica of a fourteenth-century Bavarian court chapel. Bill Gates or no, these priests think big. Since then, they’ve overhauled a historic church in downtown Kansas City, and they’re presently turning their American priory from a burnt-out shell in a borderline south-side Chicago neighborhood into something out of Counter-Reformation Rome, and I have no doubt they’re going to succeed. Lest these projects seem like archaeological transplants, they are in fact derived from a logical extrapolation from local Catholic culture—Chicago’s colorful Polish cathedrals brought back to their ultramontane source, or, as I had just discovered, Midwestern Gothic returned to its Germanic roots. (more…)

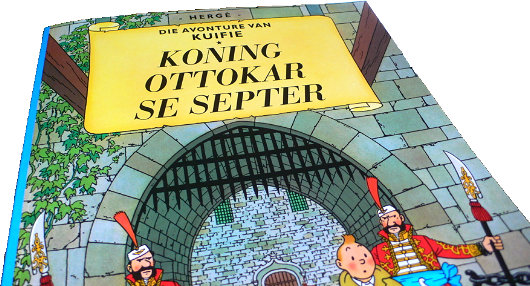

Die Koninkryk van die Swart Pelikaan

SYLDAVIA IS MY favourite country in the world. The buildings are old, the peasants are happy, and the king is ruling from his throne. Adding to my collection of Tintin books, the preponderance of which remain in New York, I know have three Afrikaans editions of Hergé’s works: Die Blou Lotus, Die Geheim van ‘De Eenhoorn’, and — my preferred among all the Tintin books — Koning Ottokar se Septer. Aside from Afrikaans, the rest of my copies are all either in French or English. I have a copy of the reprinted Tintin au Pays des Soviets and I just recently bought a copy of Tintin in the Congo, as I figured the European Union’s attempt to ban the book might make it harder to come by in years to come. I bought a copy of Le Sceptre d’Ottokar in a gas station in Brittany, one of the six special editions with a preface by Bernard Tordeur of the Hergé Foundation released in 1999/2000. Aside from Au Pays des Soviets & Le Sceptre, the only other French editions I have are L’Île Noire and Le Lotus bleu. (more…)

Celebrating a Great Scot: David Lumsden

I can’t tell you how often I come across something and think to myself “I must ask Lumsden about that”, and then suddenly realise that no such thing is possible anymore. I only had the privilege of knowing this gentle giant of a man towards the end of his life, but am grateful even for that relatively short friendship. Below is the address given by Hugh Macpherson at the Thanksgiving Service for the Life of David Lumsden of Cushnie that took place at St. Mary’s Church, Cadogan St., London on Monday, 27th April 2009. May he rest in peace.

It is difficult to mark the passing of such a remarkable personality as David Lumsden. We have done with the requiems and the pibrochs and must now look forward to celebrate an extraordinary life lived to the full.

It is difficult to mark the passing of such a remarkable personality as David Lumsden. We have done with the requiems and the pibrochs and must now look forward to celebrate an extraordinary life lived to the full.

David was a man of many parts and passions. He was a renaissance man with a wide variety of interests, and if he did not know the answer to any particular question, he certainly knew where to look it up, and in a few days there would be an informative card in the post. He had a lively curiosity and sense of adventure.

Perhaps the ruling passion in his younger life was that of rowing. He rowed at Bedford School and when he went up to Jesus College Cambridge, he joined the boat club, eventually becoming Captain of Boats. There were, I think, eventually eight “oars” on the walls of his various houses. I think that David was one of the few people I know who went to Henley to actually watch the racing, and when one went into the trophy tent his name could be found on some of the trophys. The expedition to Henley was one of the fixed points of David’s year.

He travelled round the country rather like the “progress” of a monarch of old. This progress encompassed the Boat Race, Henley, the Royal Stuart Society Dinner, the Russian Ball, spring and autumn trips to Egypt, the Aboyne Games, the 1745 Commemoration, the Edinburgh Festival, and numerous balls and dinners, including of course the Sublime Society of Beef Steaks.

Rather like clubs, David and I had a “reciprocal” arrangement: When I was in Scotland I lodged with him, and when he was in London he lodged with me, and I can tell you that there were many times when I simply could not keep up with his social whirl, in fact once or twice I distinctly fell off! I remember one particularly splendid and bibulous dinner at the House of Lords at which we were decked in evening dress and clanking with all sorts of nonsense — after many attempts to hail a taxi, David turned and said to me “You know we are so drunk they won’t pick us up. We’ll have to stagger back.” And so we wound a very unsteady path back to Pimlico, shedding the odd miniature en route.

At Cambridge, David also formed a lasting friendship with Mgr. Alfred Gilbey, Catholic Chaplain to the University, who was to have a lasting influence on David’s faith and life, and, I think, introducing him to the Sovereign Military Order of Malta, where he eventually became a Knight of Honour & Devotion.

David’s faith was an important part of his life. When he was in London he would attend this church on a Sunday morning to hear the 11.30 Latin Mass, which finished conveniently near to the opening time at one of his favourite watering holes in the Kings Road. (more…)

The Principality of South Africa

“… or some such thing.”

History has shown that good ideas often come from the humblest of sources. One such example, though regrettably one of a suggestion not put into practice, was a proposal submitted by D. M. Perceval, the humble clerk of the Advisory Council of the Cape of Good Hope colony in 1827 to his higher-ups in the Colonial Office in London. Perceval wrote to request an official seal for the British colony at the end of Africa, but he went a step further with his fairly normal request, extraordinarily suggesting that “the opportunity might be taken to erect [the Cape of Good Hope] into the Principality of South Africa, or some such thing, for the present name is really too absurd for the whole country.”

The title “Prince of South Africa” would have been part of the British Crown, and presumably available as a courtesy title for offspring, just as the eldest son is often (such as now) created Prince of Wales. Would the second son then be “Prince of South Africa”, or would the title stay with the Sovereign? “By the grace of God, King of Great Britain & Ireland, Emperor of India, Prince of South Africa, &c.” It does have a nice ring to it. (more…)

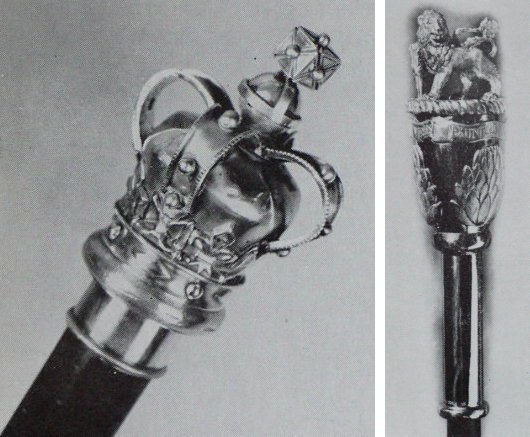

Black Rod — Swart Roede

In my post on the 1947 Royal Visit to Cape Town, I mentioned just in passing the title of the Draer van Swart Roede — or the Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod, as he is known in English. Well, here is the Black Rod itself. The original South African Black Rod (left) dates from the Parliament of the Cape of Good Hope and was adopted as the Black Rod of the Union Parliament when South Africa was unified in 1910. After the abolition of the monarchy in 1961, a new Black Rod (right) was commissioned which featured protea flowers topped with the Lion crest from the South African coat of arms.

Black Rod (the person, not the staff) was the Senate’s equivalent of the House of Assembly’s sergeant-at-arms (ampswag). The first Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod in history was appointed in 1350 and the position still exists today in the British Parliament of today. Black Rod is sergeant-of-arms of the House of Lords, as well as Keeper of the Doors. The Usher’s best-known role is having the doors of the House of Commons ceremonially slammed in his face when he acts as the Crown’s messenger during each State Opening of Parliament, a ritual derived from the 1642 attempt of Charles I to arrest five members of parliament.

In South Africa, die Swart Roede traditionally wore wore a black two- or three-pointed cocked hat, a black cut-away tunic, knee breeches, silk stockings and silver-buckled shoes, but this costume of office has undergone a process of modernisation since the 1950s. After the vast expansion of the electorate in 1994 and introduction of an interim constitution, Black Rod’s title was officially shortened to “Usher of the Black Rod” to make it “gender-neutral”. (Regrettably, the Canadian Senate has also mimicked this innovation, though it is often unofficially ignored.) When a new, permanent constitution was enacted in 1997, the Senate was replaced by the National Council of Provinces as the upper house of parliament. A new Black Rod (the staff, not the person) was introduced in 2005, but is of such a garish design that it is best left uncommented upon.

The Band-leader & the Sergeant-Major

I came across these two characters in the Castle in Cape Town, the oldest building in South Africa and still home to the Cape Town Highlanders and Cape Garrison Artillery.

Heaven in Herefordshire

In the weekly South African edition of the Telegraph, I came across a brief note marking the death of England’s oldest publican, Flossie Lane of ancient Leintwardine in Herefordshire. From the internet, I find the full version of her obituary, which is reproduced below. The Sun Inn, with its “Aldermen of the Red-Brick Bar” sounds like a splendid haven.

Flossie Lane, who died on June 13 aged 94, was reputedly the oldest publican in Britain, and ran one of the last genuine country inns

For 74 years she had kept the tiny Sun Inn, the pub where she was born in the pre-Roman village of Leintwardine on the Shropshire-Herefordshire border.

As the area’s last remaining parlour pub, and one of only a handful left in Britain, the Sun is as resolutely old-fashioned and unreconstructed today as it was in the mid-1930s when she and her brother took it over.

According to beer connoisseurs, Flossie Lane’s parlour pub is one of the last five remaining “Classic Pubs” in England, listed by English Heritage for its historical interest, and the only one with five stars, awarded by the Classic Basic Unspoilt Pubs of Great Britain.

She held a licence to sell only beer – there was no hard liquor – and was only recently persuaded to serve wine as a gesture towards modern drinking habits.

With its wooden trestle tables, pictures of whiskery past locals on the walls, alcoves and a roaring open fire, the Sun is listed in the CAMRA Good Beer Guide as “a pub of outstanding national interest”. Although acclaimed as “a proper pub”, it is actually Flossie Lane’s 18th-century vernacular stone cottage, tucked away in a side road opposite the village fire station.

There is no conventional bar, and no counter. Customers sit on hard wooden benches in her unadorned quarry-tiled front room. Beer – formerly Ansell’s, latterly Hobson’s Best at £2 a pint – is served from barrels on Flossie Lane’s kitchen floor. (more…)

Lord Clark

This clip of Kenneth McKenzie Clark, Baron Clark, OM, CH, KCB, FBA is from the end of his BBC documentary series Civilisation. Here Lord Clark complains about the lack of a true center, as he then could see none. Thankfully, Lord Clark found that center shortly before the end of his life, and was received into the Catholic Church.

“The great achievement of the Catholic Church,” said Lord Clark in Civilisation, “lay in harmonizing, civilising the deepest impulses of ordinary, ignorant people.”

First Things, Three Songs

Through an interesting post by Joseph Bottum on the First Things blog, I discover that R. R. Reno posted all three of the songs I elaborated upon in my June 2007 post “We’ve Lost More Than We’ll Ever Know”, though (so far as I can tell) he arrived at the same three without stumbling across my entry on them. I always read First Things in New York (it’s one of my favourites, and simply a must-read), but it’s sadly not available in South Africa (bar actually scraping one’s pennies together for a subscription) so I’ll just have to wade through friends’ archives when I return to the Empire State. (Or does the Society Library have a subscription? And if not, why not?).

While it has a reputation among some Catholics as being a bit too liberal & democratist, I suspect the whiff of Americanism one finds in the pages of First Things is akin to the aroma of tobacco in an old bar: the smell lingers but that doesn’t mean anyone’s actually still smoking. Nonetheless, they often feature top-notch articles and writing that are of interest to Catholics & other traditionalists.

Of tribes and traditions

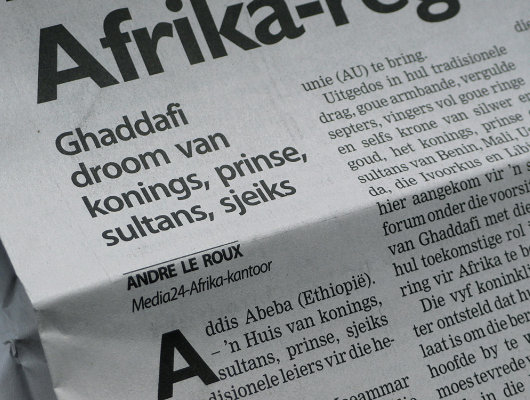

In tribal Africa, Ghaddafi expounds traditional government; Meanwhile ethnic Romanians vote to be ruled by their German neighbours.

«Ghaddafi dreams of kings, princes, sultans, sheiks»

reports the Afrikaans newspaper Die Burger.

ONE OF THE LESS-REPORTED aspects of the selection of Col. Moammar al-Ghaddafi, the tent-dwelling Libyan leader and notorious eccentric, as Chairman of the African Union was his proposal that an upper house of “kings, princes, sultans, sheiks, and other traditional leaders” be added to the Pan-African Parliament. Col. Ghaddafi has been forthright in his condemnation of democracy as ill-suited to the African continent. “We don’t have any political structures [in Africa], our structures are social,” he explained to the press. Africa is essentially tribal, the argument goes, and as such multi-party democracy always develops along tribal lines, which eventually leads to tribal conflict and warfare. “That is what has led to bloodshed,” the AU chairman posited, citing the recent example of the Kenyan elections.

Europe, of course, solved the matter of tribal difficulties by brutally uprooting long-established peoples from their native lands after the Second World War and transferring them to jurisdictions in which they would ostensibly be part, not only of the majority, but of theoretically “national” states. Cities with centuries of Polish history became Soviet, towns as German as sauerkraut became Polish, and so on and so forth. Sometimes the undesired populations of multi-ethnic places were cruelly murdered, as recent revelations from the police in Bohemia have shown.

Still, remnants of the old cosmopolitan order remain. (more…)

A Good Day in Cape Town

The South African Royal Family’s 1947 visit to “Die Moederstad”

SOUTH AFRICA IS a nation that took a long time birthing, from the first steps van Riebeeck took on the sands of Table Bay in 1652, through the tumult of the native wars, the tremendous conflict between Briton & Boer, and ultimately what was hoped would be the final reconciliation in Union of South Africa — 1910. In that year, young Prince Albert of York & of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha was just fifteen years of age, and South Africa became a dominion just weeks after his father became King George V.

Albert was the second son of a second son, so at the time of his birth (and for most of his early life) it was never expected that he would one day be King of Great Britain, Emperor of India. It was his brother’s abdication that thrust poor Bertie, as he was always known to his loved ones, upon the throne imperial. It was a cold December day in 1936 that the heralds of the Court of St. James proclaimed him George VI.

By his nature, the King was a quiet and reserved man, partly because of the stammer that impeded his speech. George VI was happiest among his family, and they accompanied him in 1947 on a long voyage aboard HMS Vanguard, to his far-off kingdom on the other side of the world, where the two oceans meet. It was the first time a reigning monarch has set foot on South African soil, and Capetonians waited in earnest anticipation to see their sovereign. How appropriate that this happy city — moederstad, or “mother-city”, of all South Africa — would be the first to receive him. (more…)

The Queen at the Armory

Queen Elizabeth II & the Duke of Edinburgh attend a ball in their honour at the Seventh Regiment Armory in New York; October, 1957.

Praying with the Kaisers

by JOHN ZMIRAK

INSIDECATHOLIC.COM

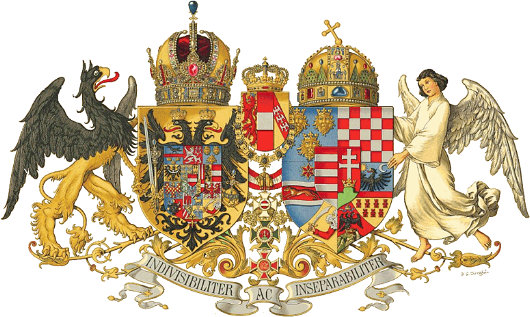

As I’m writing this column at the tail end of my first trip to Vienna, some of you who’ve read me before might expect a bittersweet love note to the Habsburgs — a tear-stained column that splutters about Blessed Karl and “good Kaiser Franz Josef,” calls this a “pilgrimage” like my 2008 trip to the Vatican, and celebrates the dynasty that for centuries, with almost perfect consistency, upheld the material interests and political teachings of the Church, until by 1914 it was the only important government in the world on which the embattled Pope Pius X could rely for solid support. Then I’d rant for a while about how the Empire was purposely targeted by the messianic maniac Woodrow Wilson, whose Social Gospel was the prototype for the poison that drips today from the White House onto the dome of Notre Dame.

And you would be right. That’s exactly what I plan to say — so dyed-in-the-wool Americanists who regard the whole of the Catholic political past as a dark prelude to the blazing sun that was John Courtenay Murray (or John F. Kennedy) might as well close their eyes for the next 1,500 words — as they have to the past 1,500 years.

But as I bang that kettle drum again, I want to set two scenes, one from a fine and underrated movie, the other from my visit. The powerful historical drama “Sunshine” (1999) stars Ralph Fiennes as three successive members of a prosperous Jewish family in Habsburg Budapest. The film was so ambitious as to try portraying the broad sweep of historical change — and, as a result, it was not especially popular. What historical dramas we moderns tend to like are confined to the tale of a single hero, and how he wreaks vengeance on the villains with English accents who outraged the woman he loved. “Sunshine”, on the other hand, tells the vivid story of the degeneration of European civilization in the course of a mere 40 years. The Sonnenschein family are the witnesses, and the victims, as the creaky multinational monarchy ruled by the tolerant, devoutly Catholic Habsburgs gives way through reckless war to a series of political fanaticisms — all of them driven by some version of Collectivism, which the great Austrian Catholic political philosopher Erik von Kuenhelt-Leddihn calls “the ideology of the Herd.”

From a dynasty that claimed its legitimacy as the representative of divine authority at the apex of a great, interconnected pyramid of Being in which the lowliest Croatian fisherman (like my grandpa) had liberties guaranteed by the same Christian God who legitimated the Kaiser’s throne, Central Europe fell prey to one strain after another of groupthink under arms: From the Red Terror imposed by Hungarian Bolsheviks who loved only members of a given social class, to radical Hungarian nationalists who loved only conformist members of their tribe, to Nazi collaborationists who wouldn’t settle for assimilating Jews but wished to kill them, finally to Stalinist stooges who ended up reviving tribal anti-Semitism. The exhaustion at the film’s end is palpable: In the same amount of time that separates us today from President Lyndon Johnson, the peoples of Central Europe went from the kindly Kaiser Franz Josef through Adolf Hitler to Josef Stalin. Call it Progress.

Apart from a heavily bureaucratic empire that spun its wheels preventing its dozens of ethnic minorities from cleansing each other’s villages, what was lost with the fall of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy? For one thing, we lost the last political link Western Christendom had with the heritage of the Holy Roman Empire. (Its crown stands today in the Imperial Treasury at the Hofburg, and for me it’s a civic relic.) Charlemagne’s co-creation with the pope of his day, that Empire had symbolized a number of principles we could do well remembering today: Principally, the Empire (and the other Christian monarchies that once acknowledged its authority) represented the lay counterpart to the papacy, a tangible sign that the State’s authority came not from mere popular opinion, or the whims of tyrants, but an unchangeable order of Being, rooted in divine revelation and natural law.

The job of protecting the liberty of the Church and enforcing (yes, enforcing) that Law fell not to the clergy but to laymen. The clergy were not a political party or a pressure group — but a separate Estate that often as not served as a counterbalance to the authority of the monarchy. No monarch was absolute under this system, but held his rights in tension with the traditional privileges of nobles, clergy, the citizens of free towns, and serfs who were guaranteed the security of their land. Until the Reformation destroyed the Church’s power to resist the whims of kings — who suddenly had the option of pulling their nation out of communion with the pope — no king would have had the power or authority to rule with anything like the monarchical power of a U.S. president. Of course, no medieval monarch wielded 25-40 percent of his subjects’ wealth, or had the power to draft their children for foreign wars. It took the rise of democratic legal theory, as Hans Herman Hoppe has pointed out, to convince people that the State was really just an extension of themselves: a nice way to coax folks into allowing the State ever increasing dominance over their lives.

A Christian monarchy, whatever its flaws, was at least constrained in its abuses of power by certain fundamental principles of natural and canon law; when these were violated, as often they were, the abuse was clear to all, and the monarchy often suffered. In extreme cases, kings could be deposed. Today, by contrast, priests in Germany receive their salaries from the State, collected in taxes from citizens who check the “Catholic” box. So much for the independence of the clergy.

The House of Austria ruled the last regime in Europe that bound itself by such traditional strictures, which took for granted that its family and social policies must pass muster in the Vatican. By contrast, in the racially segregated America of 1914, eugenicists led by Margaret Sanger were already gearing up to impose mandatory sterilization in a dozen U.S. states (as they would succeed in doing by 1930), while Prohibitionist clergymen and Klansmen (they worked together on this) were getting ready to close all the bars. As historian Richard Gamble has written, in 1914 the United States was the most “progressive” and secular government in the world — and by 1918, it was one of the most conservative. We didn’t shift; the spectrum did.

Dismantled by angry nationalists who set up tiny and often intolerant regimes that couldn’t defend themselves, nearly every inch of Franz-Josef’s realm would fall first into the hands of Adolf Hitler, then those of Josef Stalin. Today, these realms are largely (not wholly) secularized, exhausted perhaps by the enervating and brutal history they have suffered, interested largely in the calm and meaningless comfort offered by modern capitalism, rendered safer and even duller by the buffer of socialist insurance. The peoples who once thrilled to the agonies and ecstasies carved into the stone churches here in Vienna can now barely rouse the energy to reproduce themselves. Make war? Making love seems barely worth the tussle or the nappies. Over in America, we’re equally in love with peace and comfort — although we’ve a slightly higher (market-driven?) tolerance for risk, and hence a higher birthrate. For the moment.

Speaking of children brings me to the most haunting image I will take away from Austria. I spent a whole afternoon exploring the most beautiful Catholic church I have ever seen — including those in Rome — the Steinhof, built by Jugendstil architect Otto Wagner and designed by Kolomon Moser. An exquisite balance of modern, almost Art-Deco elements with the classical traditions of church architecture, it seems to me clear evidence that we could have built reverent modern places of worship, ones that don’t simply ape the past. And we still can. A little too modern for Kaiser Franz, the place was funded, the kindly tour guide told me in broken English, by the Viennese bourgeoisie. (Since my family only recently clawed its way into that social class, I felt a little surge of pride.) Apart from the stunning sanctuary, the most impressive element in the church is the series of stained-glass windows depicting the seven Spiritual and the seven Corporal Works of Mercy — each with a saint who embodied a given work. All this was especially moving given the function of the Steinhof, which served and serves as the chapel of Vienna’s mental hospital. (It wasn’t so easy getting a tour!) The church was made exquisite, the guide explained, intentionally to remind the patients that their society hadn’t abandoned them. Moser does more than Sig Freud can to reconcile God’s ways to man.

We see in the chapel the spirit of Franz Josef’s Austria, the pre-modern mythos that grants man a sacred place in a universe where he was created a little lower than the angels — and an emperor stands only in a different spot, with heavier burdens facing a harsher judgment than his subjects. No wonder Franz Josef slept on a narrow cot in an apartment that wouldn’t pass muster on New York’s Park Avenue, rose at 4 a.m. to work, and granted an audience to any subject who requested it. He knew that he faced a Judge who isn’t impressed by crowns.

As we left the church, I asked the guide about a plaque I’d seen but couldn’t quite ken, and her face grew suddenly solemn. “That is the next part of the tour.” She explained to me and the group the purpose of the Spiegelgrund Memorial. It stands in the part of the hospital once reserved for what we’d call “exceptional children,” those with mental or physical handicaps. While Austria was a Christian monarchy, such children were taught to busy themselves with crafts and educated as widely as their handicaps permitted. The soul of each, as Franz Josef would freely have admitted, was equal to the emperor’s. But in 1939, Austria didn’t have an emperor anymore. It dwelt under the democratically elected, hugely popular leader of a regime that justly called itself “socialist.” The ethos that prevailed was a weird mix of romanticism and cold utilitarian calculation, one which shouldn’t be too unfamiliar to us. It worried about the suffering of lebensunwertes Leben, or “life unworthy of life”–a phrase we might as well revive in our democratic country that aborts 90 percent of Down’s Syndrome children diagnosed in utero. So the Spiegelgrund was transformed from a rehabilitation center to one that specialized in experimentation. As the Holocaust memorial site Nizkor documents:

In Nazi Austria, parents were encouraged to leave their disabled children in the care of people like [Spiegelgrund director] Dr. Heinrich Gross. If the youngsters had been born with defects, wet their beds, or were deemed unsociable, the neurobiologist killed them and removed their brains for examination. …

Children were killed because they stuttered, had a harelip, had eyes too far apart. They died by injection or were left outdoors to freeze or were simply starved.

Dr. Gross saved the children’s brains for “research” (not on stem cells, we must hope). All this, a few hundred feet from the windows depicting the Works of Mercy. Of course, they’d been replaced by the works of Modernity.

We’re much more civilized about this sort of thing nowadays, as the guests at Dr. George Tiller’s secular canonization can testify. In true American fashion, our genocide is libertarian and voluntarist, enacted for profit and covered by insurance.

I will think of the children of the Spiegelgrund tomorrow, as I spend the morning in the Kapuzinkirche, where the Habsburg emperors are buried — and the Fraternity of St. Peter say a daily Latin Mass. As I pray the canon my ancestors prayed and venerate the emperors they revered, I will beg the good Lord for some respite from all the Progress we’ve enjoyed.

Blessed Karl I, ora pro nobis.

[Dr. John Zmirak‘s column appears every week at InsideCatholic.com.]

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories