Tradition

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Mexican Diplomats

Don Manuel Iturbe, envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary, sits wearing the full civil uniform of an ambassador while the two attachés, Don Miguel Iturbe and Don Juan Beistegui, stand wearing lower grades of diplomatic dress.

All three wear the Order of St Stanislaus — the Polish royal order incorporated into the Romanov orders in 1832.

The records of the Mexican congress shows that Manuel Iturbe was authorised to accept Grand Cross of the order while Miguel (who I presume was Don Manuel’s son though I can’t confirm) and Juan Beistegui had to settle for the ordinary Cross of St Stanislaus.

Know Your Counties!

A very useful resource: the Wikishire map

While we all still live in the ruins left by the Tyrant Heath when he destroyed local government in this realm, it is always re-assuring to hear of those who perpetuate the old ways of eternal England. Heath created ‘administrative counties’ on top of the traditional counties, and these new counties ran riot over ancient boundaries.

For example, Abingdon, which is the county town of Berkshire, now finds itself confusingly administered by Oxfordshire County Council. Worse, many newly arrived emigrants from London and other parts know no better and refer to Abingdon as being ‘in’ Oxfordshire rather than merely being administered by it.

Berkshire’s beautiful baroque County Hall now sits empty and unused, frozen in formaldehyde and reduced to the status of a mere museum rather than a living, breathing thing.

Contrary to the belief of some, traditional counties have never been abolished and they are even perfectly valid for postal addresses. Many, when doing their annual round of Christmas cards, prefer to include the traditional county when addressing envelopes.

If you are unsure of what county your addressee lives in, there is now a very useful resource from a website called Wikishire: a Google map of all the traditional counties in the home nations — England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales.

Simply plug in the post code or town name and it will show you the proper county in which the spot in question is located. A happy marriage of new technology and the old, undying ways!

Fête du Dominion

à tous nos amis canadiens!

Happy Dominion Day

to all our Canadian friends!

Canada is one of the most fascinating and interesting realms on the face of the earth, though the Canadians are a curiously humble people despite their immense achievements.

I’ve written some odd bits and bobs of Canadiana over the years, and thought a small selection of which might prove a suitable way of celebrating the great dominion’s national day.

The Feast of St Valentine in the Cape

Die fees van Sint Valentyn in die Kaap

A nice tradition!

’n Lekker tradisie!

Earls, Shires, Hides, and Hundreds

What the Practice of ‘Pricking the Lites’ Tells Us About Territorial Division in Anglo-Saxon England

As cheekily noted by Ned Donovan on his Twitter feed, HM the Q has recently engaged in the old practice of ‘pricking the lites’ to appoint High Sheriffs for the three ceremonial counties of Lancashire, Greater Manchester, and Merseyside. But in order to know what ‘pricking the lites’ is it’s worth looking at the territorial division of Anglo-Saxon England and the old offices that emerged therefrom.

In those days, the land was divided into hides, a hide being the amount of land on which a family lived and supported itself. Ten hides together were known as a tithing, and ten tithings were collectively a hundred.

As hundreds go, the best-known today are the Chiltern Hundreds because of the parliamentary role they play. Members of Parliament are not allowed to resign, but nor are they allowed to hold an office of profit under the Crown.

So whenever an MP wants to resign, he or she is appointed Crown Steward and Bailiff of the three Chiltern Hundreds of Stoke, Desborough, and Burnham and, having accepted such office, is deemed to have disqualified themselves from continuing to sit in the House of Commons. (The Manor of Northstead is also used alternately with the Chiltern Hundreds.)

Anyhow, each hundred was supervised by a constable, and groups of hundreds were collected into shires. Each shire was overseen by an earl, of whom the French equivalent is a count, so after the Normans turned up shires became more often known as counties. These now divvy up territory across the English-speaking world, from Kenya to California.

Each level of these Anglo-Saxon divisions had a relevant court for decision-making, and the officer who administered or enforced these decisions was known as the reeve. Amongst these titles – town-reeve and reeve of the manor, etc. – there was the shire-reeve, or sheriff as it was contracted.

In the 1970s, for reasons unknown to me, all the sheriffs in England & Wales were elevated to high shrievalties.

Every February or March, a parchment is prepared for the Queen in her capacity as Duke of Lancaster with three names of candidates for high sheriff in the three current ceremonial counties covered by the old duchy. This parchment is known as the lites (a cognate of ‘list’, I believe).

At a meeting of the Privy Council, the Queen takes a silver bodkin and pricks the parchment next to the name of the candidate she chooses to be high sheriff. In practice, this is always the first name on the list, and customarily the following names move up a notch and serve in later years.

A similar process takes place for the Duke of Cornwall to appoint their high sherriff but without the aid of the Privy Council.

Judging Dress

After some absence, The Sybarite has returned and, in A Love Supreme, he weighs in on the very important matter of judicial dress.

I am, it will surprise no-one to know, deeply traditionalist in such matters. I can see the argument for discarding formal court attire in cases involving children, who might be intimidated by wigs and gowns (as a child, I myself would have been as happy as a pig in the proverbial). But I feel strongly that “work clothes”, whether worn by judges, barristers, politicians or clerks in Parliament, are important. They are part of the persona. You are not Alf Bloggs, you are Mr Justice Bloggs and you are performing an important public role. When you put on the clothes, you put on the role. Of course, I am fighting a rearguard action here – I know that the tide of public opinion is against me. If the clerks at the Table in the House of Commons still wear wigs in ten years’ time, I will be (pleasantly) surprised.

As the Supreme Court was set up in the modish New Labour years, it was inevitable they would dispense with much of the ceremonial. The Justices wear lounge suits to hear cases, though I think in some cases the barristers still wear wigs and gowns. The one concession has been the black-and-gold gowns which the Justices don for special occasions. These are fine so far as they go – and, as observed above, Lady Hale of Richmond likes to accessorise hers with a Tudor bonnet – though they bear on the back the badge of the Supreme Court, which I think looks a bit tacky and smacks of footballers’ names and numbers on the back of their shirts. But they also look a bit odd worn over lounge suits or equivalent. At least successive Lord Chancellors since the role was recast by Blair have retained formal court dress for high and holy days. Mind you, the current occupant, Miss Truss, does look a bit like the principal boy in a pantomime when she wears knee breeches. But fair play to her for continuing to wear the traditional robes, even if the full-bottomed wig seems now to have gone the way of the dodo.

It could be worse. The Supreme Court Justices could wear ghastly zip-up gowns like their American counterparts – you just know they’re made of nylon – over their suits, though I have some time for Justice Ginsberg for adding a lace jabot to tidy up her garb a little. But ceremonial is something that Britain does so well. The Supreme Court could have looked so much better with Justices in gowns and traditional judicial clothing. A wig here and there wouldn’t go amiss.

I couldn’t agree more. Especially on the matter of the badge of the Supreme Court on the back on the gowns, which is simply naff. (See image below.)

But why do the justices of the Supreme Court have (what I think of as) chancellorial gowns anyhow? What is the origin of this style of black-and-gold gown? Did it start with the Lord Chancellor and spread to the Speaker or vice versa? Or have some species of judge always worn chancellorial gowns? The chancellors of universities have likewise adopted it, though its precise form varies from institution to institution, as one might expect in matters of academic dress.

Incidentally, I was speaking with Bob Geldof the other day about Senator W. B. Yeats, about whom Mr Geldof has done a documentary. As we were discussing Yeats’ contribution to the Irish Senate, Mr Geldof mentioned that Yeats had been in discussions with Hugh Kennedy, the Chief Justice of the Irish Free State, about introducing new designs for Irish judicial dress. The results, according to just about everyone, left much to be desired and so the British tradition carried on for the most part. As is so often the case, doing nothing is the least bad option.

Past and Future Meet in Peru’s Navy

Lima’s Latest Warship Boasts Four Masts and Full Rigging

Today the Peruvian Navy’s newest ship, the BAP Unión, returns to its home port of Callao after an 8,900-mile tour at sea that took in eight countries over 98 days. But though commissioned earlier this year by then-President Ollanta Humala, the Unión isn’t some grey-painted stealth frigate but a four-masted, steel-hulled, full-rigged barque. Named after a corvette that saw action in the War of the Pacific, the Unión was laid down at Callao’s SIMA shipworks in 2010, launched in 2014, and was commissioned this past January as the primary training vessel of the Peruvian fleet.

The unimaginative might be surprised that such old-school ships are being used to train modern sailors, but the Unión’s Commander Roberto Vargas is unambiguous.

“On modern warships, working with computers and satellites all the time, we forget that we have to learn the essentials of sailing,” Commander Vargas told the Miami Herald.

“On a ship like the Unión, these cadets learn leadership, they learn cooperation, they learn group spirit. It’s impossible to work alone with these big sails — you have to work with other people. And most of the basics, like navigation and oceanography, are the same.”

Many other Latin American countries use tall ships as naval training vessels. Argentina’s ARA Libertad was the subject of an attempted seizure by foreign vulture funds seeking payments on debts defaulted upon in 2002.

While most date from the 1960s (Colombia’s Gloria), ’70s (Ecuador’s Guayas; Venezuela’s Simón Bolívar), or ’80s (Mexico’s Cuauhtémoc), Chile’s Esemeralda was launched in 1946. The grande dame of them all is Uruguay’s schooner the Capitán Miranda, launched in 1930 but docked since 2013 awaiting decisions on upgrades.

One analyst notes that even two-hundred years later the old imperial connections are still thriving in the strong Spanish influence on many of these ships:

The Peruvian state-controlled shipyard SIMA (Servicios Industriales de la Marina) constructed the Union in its shipyard in the port of Callao, but the Spanish company CYPSA Ingenieros Navales cooperated in the vessel’s structural design.

As for other ships, many were constructed by Spanish companies. For example Colombia’s Gloria, Ecuador’s Guayas, Mexico’s Cuauhtemoc, and Venezuelan’s Simon Bolivar were all manufactured by Astilleros Celaya S.A., while Chile’s Esmeralda was obtained from the Spanish government which constructed it at the Echevarrieta y Larrinaga shipyard in Cadiz.

One exception to the rule is Brazil’s Cisne Branco, which was constructed by the Dutch company Damen Shipyard.

Given the return to tradition in Peru’s army that we had previously reported on, it’s a pleasure to see this continuing in the country’s navy. Peru continues to show the world that another future is possible.

Entering the old harbour of Havana, Cuba.

Above and below, decked out for commissioning in Callao.

President Humala at the commissioning ceremony.

Best Foot Forward in Peru

A return to tradition for the Peruvian armed forces

One of the results of Peruvian voters electing the left-wing nationalist Lt Col Ollanta Humala as the president of their republic in 2011 has been a renewal of the traditions of the country’s armed forces – under this Excelentísimo Señor Presidente there has been a return to a much more traditional style of military uniform. A long decline in standards only accelerated during the first presidency of the liberal Alan García (1985-1990) who altered the Changing of the Guard at the Government Palace, while his populist successor Alberto Fujimori had the more pressing task of defeating an insurgency to turn his attention to such matters.

It’s often alleged that cultural trends in the Americas have long been riven by a conflict between one tendency favoruing European influences against another which favours national or indigenous inspiration. This dichotomy seems false, as the Americas are at their best when they take the finest in the European tradition and develop it in a new way with the addition of more local flavours.

In the nineteenth century, however, the European was in the ascendant, and particularly in South American militaries which relied upon European advisors to update and train their armed forces. Countries like Colombia and Chile imported Prussian advisors, which has given their militaries a Teutonic air to this day (viz. Colombia’s pickelhaube and Chile’s parada militar).

In Peru, however, it was the French who were brought in to bring the army up to speed, and that lasting influence is obvious from the uniforms seen here at a recent passing-out ceremony at the Escuela Militar de Chorrillos attended by the President. No pickelhaube here, the kepi reigns supreme.

It’s not turning the clock back: it’s choosing a different future. (more…)

Tradtastic Hertfordshire

The bishops of England & Wales cunningly arranged for the Feast of the Epiphany to fall on the actual Epiphany this year. We had a great big festive lunch at our favourite little Italian place in South Ken, but the night before I went out to Hertfordshire, where I witnessed the tradition of a door being CMB’d with holy chalk for the new year (above).

Those unaware of this tradition can read a bit more here. The C+M+B stands both for Christus mansionem benedicat (“Christ bless this house”) and the names of the Three Magi: Caspar, Melchior, and Balthasar.

The Start of Something Big in Argentina

The first-ever Nuestra Señora de Cristiandad Pilgrimage to Luján

SMALL SEEDS, IF well-planted and tended to, flower into much larger growths. On a Friday morning last month, just four pilgrims set out from the town of Rawson in the Buenos Aires province of Argentina, but by the time they reached their destination — a Latin Mass in the Marian basilica of Luján — their numbers swelled to nearly a hundred. The pilgrimage of November 5th, 6th, and 7th, under the patronage of ‘Our Lady of Christendom’ (Nuestra Señora de Cristiandad) was inspired by the traditional Paris-Chartres pilgrimage every Pentecost weekend. The organisers hope that, like the Chartres pilgrimage, this trek to Luján will become an annual recurring event.

“Renewing Christendom in Argentina” was the theme of this year’s pilgrimage, which “seeks to promote the rich tradition of the Roman Catholic Church for our times” the organisers announced in a press release after its completion.

“This new 100-kilometre pilgrimage was an act of reparation and praise to God, imploring the salvation of souls through the renewal of Christian culture and the rediscovering of the bi-millennial tradition of the Church.” (more…)

The Most British Place in the World?

The Islands of the Anglo-Caribbean: Where Old Britain Lives

Spoke to a friend recently, who just had a friend of her’s report back after a six-month stint in the Bahamas. “This is the Britain my grandparents always told me about. It must be the most British place on earth. Men in ties and blazers and women in lovely hats. Just the right mixture of formal and laid-back.” (more…)

Chartres MMX

The Pentecost Paris-Chartres Pilgrimage 2010

PENTECOST commemorates the descent of the Holy Spirit, often considered the birthday of the Church. Each year, this great feast of the Church is marked by the pilgrimage from the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris on the Île de la Cité (above) to Notre-Dame de Chartres in the Orléanais by pilgrims young and old devoted to the traditional form of the Latin rite. The pilgrimage, often a feast of flags and banners, takes three days beginning on the Saturday of Pentecost weekend, continuing through the great feast itself, and arriving in Chartres on Pentecost Monday (which is still a public holiday in France). This year, Cardinal Vingt-Trois, the Archbishop of Paris, graciously led Benediction on the second day of the pilgrimage, and met with and blessed individual pilgrims. (more…)

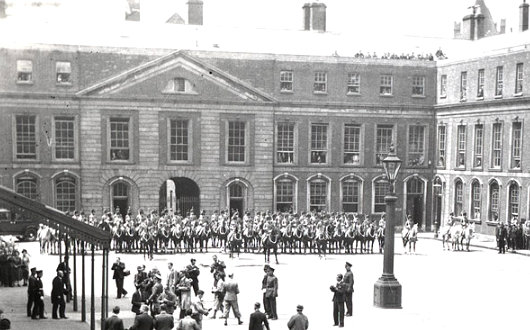

The Blue Hussars

Ireland’s Mounted Presidential Escort

WHEN BRITAIN FINALLY granted dominion status to Ireland, her longest-held possession, in the 1920s it unfortunately also signalled the end to a long tradition of Irish service in H.M. Forces. Well, this is not entirely true — thousands of Irishmen from both Ulster and the Republic continue to volunteer for the Army, Royal Navy, and RAF (the Royal Irish Regiment and the Irish Guards receiving the lion’s share) with an exemplary record of service to the Crown. But numerous other regiments with long lineages rolled up their colours in a dramatic ceremony at Windsor Castle in 1922. (An aside: one of those five regiments was the Connaught Rangers whose former name — the 88th Regiment of Foot — inspired the later re-designation of a New York Guard unit as the 88th Brigade NYG, of which yours truly is a veteran and my uncle the former commander).

WHEN BRITAIN FINALLY granted dominion status to Ireland, her longest-held possession, in the 1920s it unfortunately also signalled the end to a long tradition of Irish service in H.M. Forces. Well, this is not entirely true — thousands of Irishmen from both Ulster and the Republic continue to volunteer for the Army, Royal Navy, and RAF (the Royal Irish Regiment and the Irish Guards receiving the lion’s share) with an exemplary record of service to the Crown. But numerous other regiments with long lineages rolled up their colours in a dramatic ceremony at Windsor Castle in 1922. (An aside: one of those five regiments was the Connaught Rangers whose former name — the 88th Regiment of Foot — inspired the later re-designation of a New York Guard unit as the 88th Brigade NYG, of which yours truly is a veteran and my uncle the former commander).

The forces which became the Irish Free State Army, given their irregular nature, lacked a ceremonial tradition (though, had I been around and Michael Collins invited me to do so, I would’ve happily manned the desk in the IRA Office of Protocol, Ceremony, and Feathery Hats). In 1932, Dublin hosted the International Eucharistic Congress — a big event in those days, sadly reduced in stature — which meant that dignitaries of great importance would take this opportunity to visit the Irish capital. (more…)

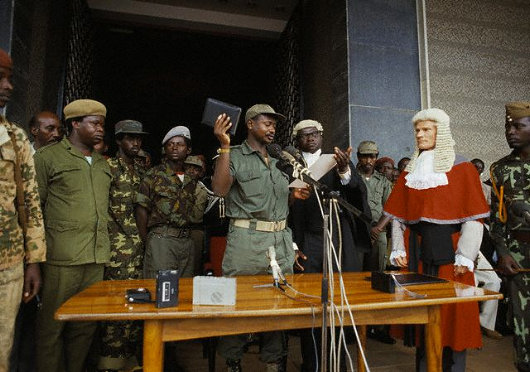

The Informal and the Formal

I can’t help but be amused by the brash contrast of the informal and the formal in this photo of Yoweri Museveni’s inauguration as President of Uganda in 1986. The years after Idi Amin’s overthrow in 1979 were almost as turbulent as the rule of the alleged cannibal. Milton Obote, the man Idi Amin had overthrown to gain power, returned to the presidency for five years during which Uganda’s troubles never ceased. In January 1986, the Obote government collapsed after Museveni’s rebel army seized the capital. The old emperor had fled, and the apparatus of state hailed the new emperor as their own. Museveni, Holy Writ in hand and guided by a clerk as the Chief Justice looked on, took the oath of office and formally ascended to the presidency of the nation. (more…)

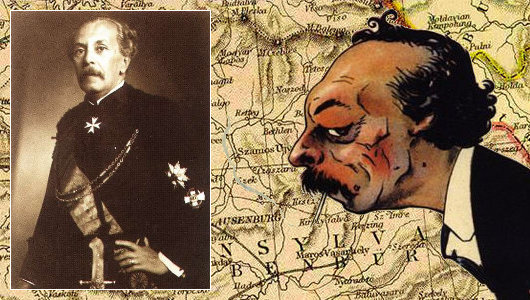

‘The Tolstoy of Transylvania’

In his column in the Daily Telegraph, former editor Charles Moore praises Miklos Banffy as ‘the Tolstoy of Transylvania’. Ardent Banffyites like myself are always pleased when the Hungarian novelist gets attention in the English-speaking world, which happens all too rarely. I can’t remember how on earth I stumbled upon the works of Banffy, probably through reading the Hungarian Quarterly, a publication that — covering art, literature, history, politics, science, and more — is admirably polymathic in our age in which the specialist niche is worshipped.

To put it simply, Banffy is a must-read. If you love Paddy Leigh Fermor’s telling of his youthful walk from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople (the third and final installation of which we still await), then Miklos Banffy will be right up your alley. Start with his Transylvanian trilogy — They Were Counted, They Were Found Wanting, and They Were Divided.

The story follows two cousins, the earnest Balint Abady and the dissolute László Gyeroffy, Hungarian aristocrats in Transylvania, and the varying paths they take in the final years of European civilization. The novels “are full of love for the way of life destroyed by the First World War,” Charles Moore points out, “but without illusion about its deficiencies.”

Three volumes of nearly one-and-a-half thousand pages put together, they make for deeply, deeply rewarding reading, transporting you to the world that ended with the crack of an assassin’s bullet in Sarajevo, 1914.

After finishing his trilogy, Banffy’s autobiographical The Phoenix Land is worthwhile; some of the real events depicted shadow those in the fictional novels. As previously mentioned, it contains a description of the last Hapsburg coronation (that of Blessed Charles) and numerous amusing tales.

After that, I’m afraid you will have to learn Hungarian, which I have neglected to do, as no more of this author’s oeuvre has yet been translated into English.

Chartres 2009

While there are but a few days to go, I can’t let this year depart without finally showing you photos of the 2009 Paris-Chartres pilgrimage which takes place every year on the weekend of Pentecost. (See 2008, 2005, 2004). The theme for the upcoming 28th Pilgrimage from Notre-Dame de Paris to Notre-Dame de Chartres was recently announced by the Association Notre-Dame de Chrétienté which organises the event. The 28th Pilgrimage will take place on the 22nd, 23rd, and 24th of May 2010, with the theme “The Church is Our Mother”. The themes for the individual days will be: 1) Teaching, under the patronage of St. Peter; 2) Sanctifying, under the patronage of St. Jean Vianney, the Curé d’Ars; 3) Governing, under the patronage of St. Pius X.

The following photos, however, are compiled from various sources, and show the pilgrimage which took place this past Pentecost. (more…)

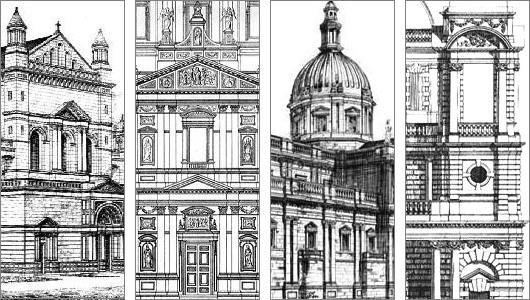

Brompton Oratory as It Might Have Been

Failed Entries of the 1878 London Oratory Architectural Competition

ARCHITECTURAL COMPETITIONS have always fascinated me because they give us the opportunity to glance at multiple executions for a single concept, to see different minds solve a “problem” with their own particular formulas and theorems. The designs of many of the world’s prominent buildings were chosen by competition, perhaps the Palace of Westminster — Britain’s Houses of Parliament — is most famous among them. When the Hungarian Parliament held a competition to design a grand palace to house the body, it found the top three prize designs so compelling that it built the first-prize design as parliament and the second and third places as government ministries nearby. To my surprise, I have only ever come across one book which adequately surveyed the subject of competitive architecture, Hilde de Haan’s Architects in Competition: International Architectural Competitions of the Last 200 Years. Most of the contests covered in the book are, naturally, for government buildings of national importance — private clients usually have a very firm idea of what they want and choose an architect accordingly.

One building not mentioned in the book but nonetheless very dear to me (and no doubt to many readers of this little corner of the web) is the Church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary of the Congregation of the London Oratory, more popularly known to friend and foe alike as the Brompton Oratory. It was the first church in Britain in which I ever heard mass, the summer after kindergarten when I was still but a tiny, blond-haired whippersnapper, in the midst of my first visit ever to the Old World, and the Oratory made quite a strong impression upon my young mind. It is usually one of my very first ports of call whenever I am in the capital, and I once even managed to slip in having just arrived at Heathrow while making my way to King’s Cross and the train to Scotland.

The Brompton Oratory is known for having good priests, traditional liturgy, and beautiful architecture. The final design was by one Herbert Gribble, but there was quite a bit of to-ing and fro-ing before Gribble was selected. The temporary church which had been erected on the site had been condemned by one critic as “almost contemptible” in its exterior design. In 1874, the Congregation of the Oratory (which is to say, the priests) put out an appeal for funds towards the construction of a permanent church. The 15th Duke of Norfolk obliged with £20,000 to get the ball rolling, and the next year a design by F. W. Moody and James Fergusson was agreed upon in principle. But the Reverend Fathers soon began to get creative and hatch ideas and contact other architects and very soon it was claimed that there were as many counter-proposals as there were priests of the Oratory, and perhaps more. A pack of clerics supported a suggested design by Herbert Gribble, but no accord could be reached among the Congregation as a whole.

In January 1878, then, it was announced that a competition would take place to decide the design of the permanent church of the London Oratorians. First prize was £200, with £75 for the runner-up. All entries had to meet the certain requirements drawn up by the Congregation. The style was to be “that of the Italian Renaissance”. The sanctuary, at least sixty feet deep, must be “the most important part of the Church. … Especially the altar and tabernacle should stand out as visibly the great object of the whole Church.” The minimum width of the nave was fifty feet, and maximum length 175 feet. Subsidiary chapels must be “distinct chambers”, not merely side altars. One aspect not mentioned was the projected execution costs of the designs — “an omission criticized by architectural journalists and disgruntled competitors,” the London Survey tells us, “whose designs called for expenditure ranging from £35,000 to £200,000”.

Over thirty entries were submitted to the competition, and Alfred Waterhouse was commissioned by the Fathers to provide comment on the submissions. Significantly, George Gilbert Scott, Jr. submitted a design, though I haven’t been able to get my hands on any depictions of it. Waterhouse praised it as “of no ordinary merit. … I feel that it is impossible to speak too highly of its beauty, its quiet dignity, its absence of all vulgarity and its concentration of effect around the high altar.” (more…)

The Would-Be King of New Zealand

Brigadier the Right Honourable Sir Bernard Fergusson,

Baron Ballantrae, KT, GCMG, GCVO, DSO, OBE

Left, Lord Ballantrae in his robes of office as Chancellor of the University of St Andrews; Right, as Governor-General of New Zealand with former Prime Minister Sir Walter Nash.

Over at Curated Secrets, Stephen Klimczuk takes a brief wander through Clubland, mentioning the illustrious Bernard Fergusson, who was known for “the skill with which he could toss his monocle in the air and catch it in his eye”. Stephen’s co-author on Secret Places, Hidden Sanctuaries, the Much Hon. Laird of Craiggenmaddie, chimes in on the commentbox, bringing to light that “when he was serving under Orde Wingate with the Chindits in Burma, among the supplies dropped by the RAF to those doughty warriors was a supply of monocles for Fergusson, since the damage/loss rate was so high in the jungle.”

Fergusson has always fascinated me, not only because he was the Chancellor of my university, but also because he has the best claim to the throne of New Zealand should the Land of the Long White Cloud ever decide to dispense with the House of Windsor. Lord Ballantrae (as Fergusson was ennobled) served as Governor-General of New Zealand, his own father served as Governor-General of New Zealand, and both his grandfathers served as Governor of New Zealand before the antipodean kingdom became a dominion. Rather appropriately, his son and heir is currently serving as Her Majesty’s High Commissioner to New Zealand, which is now the highest office of the British government in those islands.

Stephen mentions other fun stories of Clubland, such as the waggish response of the dinner guest who was kept waiting for Hermann Goering at one club before the war: “‘I have been shooting,’ said Goering. ‘Animals, I hope?’ was the quite reasonable question in response.”

Argentines Recall Blessed Emperor

An Argentine correspondent informs us that the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass was offered on October 28th at the Church of St. Boniface, the German-speaking parish of the Archdiocese of Buenos Aires, to commemorate the fifth anniversary of the beatification of Blessed Charles, Emperor of Austria and Apostolic King of Hungary. The mass was organized by Viscountess Huges Stier de Saint Jean (née Princess Isabelle Auersperg-Breunner), whose mother was a descendant of the Emperor Franz Joseph through his daughter Valerie. The Mass was offered in Spanish and German, with the prayers of intention read in those languages as well as Hungarian, Slovak, Ukrainian, Croatian, and Italian.

Category: Charles of Austria

The World Turned Upside Down

— philosopher George Santayana

I can’t remember who it was that, watching the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Iron Curtain, said never in his right mind did he expect that within just a decade Washington would be the chief propagator of worldwide revolution and the Kremlin would be a relatively conservative power, guarding jealously its local sphere of influence. What could add more of a dash of the absurd (and yet, eminently sensible) than the Russian government, facing the worst crisis of population decline of any major power, promoting larger families with a poster campaign quoting the conservative American philosopher George Santayana.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories