The European

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The Newspaper for People in Sunglasses

Watch this splendidly dated television advertisement for The European from 1991. In that year, the Soviet Union still existed, Eastern Airlines closed after sixty-two years in aviation, the IRA was still bombing London, Archbishop Lefebvre went on to his eternal reward, Édith Cresson became premier of France, and the Dow Jones closed above 3,000 for the first time — today it closed at 11,532.88.

The European I grew up with

When I was a kid, The European — the weekly broadsheet that billed itself as “Europe’s national newspaper” from 1990 to 1998 — was my favourite newspaper and was an indelible part of our Sunday routine in the Cusack household. First Mass, then a trip to the pastry shop, then pick up The European at the newsagents next door, and back home to read and munch al fresco.

The paper was fiercely Euro-federalist until Andrew Neil took over, so I suspect were I to look back on a few copies now, I would probably strongly disagree with its politics. The late Peter Ustinov was a columnist, and he was not just a European integrationist but indeed a major supporter of world federalism (i.e. the abolition of nations and the rule of the planet by a single government; in theory democratic but inevitably a dictatorship of course).

Nonetheless, it was a very broad paper, with news from all across the continent from Cork to Constantinople, and I have no doubt its coverage played at least some role in the formation of your humble and obedient scribe.

The life & death of The European

An idea before its time or the mad dream of a master swindler?

The inception of The European at the dawn of the 1990s was emblematic of the age. Triumphant scenes of joyful crowds tearing down the Berlin Wall in 1989 sparked exhilaration across the continent and the high spirits from the fall of the Iron Curtain were transformed into Euro-phoria as the ideal of a ‘United States of Europe’ now seemed a very real possibility. The media and publishing magnate Robert Maxwell vigorously supported ‘the European ideal’ and founded The European newspaper to act as a cheerleader for that ideal. Rolling from the printing presses within a year of the Wall’s fall, the newspaper had nonetheless folded by the time the Amsterdam Treaty was ratified in 1999 despite the continued growth in the size and power of European institutions. But the story of the rise and fall of Maxwell’s newspaper — the life and death of The European — is itself indicative of the strengths and weaknesses of the European project itself.

Robert Maxwell’s euro-enthusiasm might be explained by his transnational roots. “Captain Bob” (as Private Eye labeled him) was born Ján Ludvík Hoch in 1923 into a poor Jewish family in a small town in Carpathian Ruthenia — then in Czechoslovakia, now in the Ukraine — and escaped to Great Britain in 1940. He entered the British Army shortly thereafter as a private but his natural intelligence and gift for languages meant that by the war’s end he was a captain, having also been awarded the Military Cross for gallantry.

Using the many contacts he had made amongst the Allied occupation officials, Maxwell went into business as the British and American distributor for Springer Verlag, a German scientific publishing firm. In 1951, he went into publishing on his own when he purchased Pergamon Press, a textbook-printing subsidiary, from Springer Verlag, turning the company around and making handsome profits from the endeavour. A socialist, despite his business acumen, he was elected to the House of Commons in 1964 on the nomination of the Labour party, losing his seat six years later.

Through Pergamon Press, he gradually began accumulating media interests. He lost the battle to buy the News of the World to Australia’s Rupert Murdoch, who duly emerged as his arch-nemesis. By the middle of the 1980s, however, Maxwell owned the London-based Daily Mirror and Sunday Mirror, the Daily Record and the Sunday Mail (both Scottish), as well as other newspapers, a number of publishing houses, a record label, the Berlitz language schools, and half of MTV Europe, and the Oxford United Football Club.

But conventional newspapers, no matter how numerous, did not satisfy the massive ego which had become one of Maxwell’s most notorious characteristics. In June 1988, he began planning for a transnational, pan-European daily newspaper, The European, printed in colour with articles in English, French, and German. Maxwell was a keen proponent of European integration and saw the new title as a method of bridging the gap between Britain and the Continent, as well as hoping that it would act as a counterweight to the well-established American weeklies Time and Newsweek.

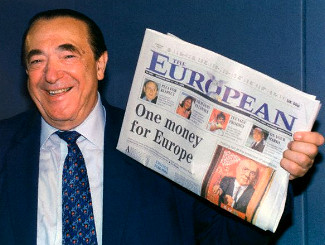

Maxwell brandishing issue No. 1 of The European

Maxwell’s ideal for the newspaper proved impossible to realize immediately, and when The European finally emerged on newsstands in May, 1990, it had been brought down in scope to an English-language weekly newspaper. The title emblazoned across the top — with an emblematic white dove hovering above the continent, a copy of the newspaper firmly clasped in its beak — the first copy of The European proclaimed it would bolster ‘the supporters of the integration of Europe’. Divided into three sections — the main news section, Business, and a tabloid-sized culture review named Élan — the paper made a bold use of colour long before most other broadsheets converted from black-and-white.

One million copies of the first issue were printed by Maxwell, with a guarantee to advertisers that the weekly would settle down in six months with a circulation of at least 225,000. Three months after the launch (July 1990), Maxwell claimed a circulation of 340,000 for his pet project, divided between 187,000 in Great Britain and 153,000 on the Continent. The first audited sales figure, however, came out in February 1991 with 226,000, below Maxwell’s promise to advertisers. That month, Maxwell replaced the founding editor, Ian Watson, with John Bryant, who had edited the acclaimed Sunday Correspondent during that newspaper’s brief existence.

As the sales figures continued to settle downwards, Maxwell grew less comfortable with realistic circulation estimates and he began a number of schemes aimed at driving up the numbers. That February, it was decided that ‘significantly different’ U.K. and overseas versions would be printed. In October 1991, just a few months later, Maxwell attempted to introduce an edition specific to North America, where officially 15,000 copies of the U.K. edition were sold each week. By the end of the month, however, the scheme was abandoned, and many of the hacks in The European‘s London headquarters were reduced to working a three-day week to cut corners, while some were made redundant outright.

The European aside, Maxwell’s empire was coming apart at the seams. High interest rates and a general recession were bad for business overall, but investigations had been launched into various dodgy business practices throughout Maxwell’s companies. Profits had been overstated while losses were hidden away. Money had been looted from corporate pension funds to prop up entities personally owned by Maxwell and to artificially inflate share prices. The London Metropolitan Police were even compiling a file on Maxwell’s war years, towards the aim of charging him with war crimes for killing at least one German civilian.

On November 5, 1991, Robert Maxwell disappeared from his super-yacht sailing off the Canary Islands, and his body was found floating in the Atlantic shortly afterward. Officially ruled an accidental drowning (the more imaginative claimed he was murdered), most assumed that “Captain Bob” had taken his own life rather than face the unravelling of his business empire and its supportive web of deceit. Maxwell was buried five days later on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, with Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir delivering the eulogy.

Ian Maxwell, the paper’s chief executive and son of the dead proprietor, announced to the assembled staff the true extent of his father’s crimes and their consequent impact for the newspaper, bursting into tears before making a quick exit from the newsroom. Not only were the various Maxwell operations suddenly and very seriously bankrupt, but it became apparent that Maxwell had continually fiddled with the newspaper’s circulation figures. “Rumour had it,” wrote one editor, Richard Holledge, “that copies were being burnt by that year’s particular brand of rioting French” outside the continental print site in Beauvais, and “[t]heir charred numbers were added enthusiastically to the figures”. “A better rumour,” bearing in mind Maxwell’s end, Holledge continued, “was that copies were shipped across the Channel, lost overboard and also added to the circulation”.

Bereft of its chief architect and founder, it was widely thought that The European would have to call it a day and cease operations. The remaining staff held a raucous Christmas party, presuming it would be the last undertaking of ‘Europe’s national newspaper’. But the party was far from over. Deputy editor Charles Garside, an old hand with experience in many a Fleet Street newsroom, bought the title and organised the staff, who worked without pay over the Christmas holiday in order to keep The European alive long enough until a suitable owner could be found. On one of the first weekends of 1992, Garside flew to Monte Carlo, returning the following Monday with new proprietors for The European: the famously reclusive Barclay brothers.

Identical twins, David and Frederick Barclay first made their money with a hotel they expanded into a chain and were not previously involved in the media. Under the Barclay regime and with Garside at the editorial helm, the aim was not so much to advance The European, as it was under the circulation-mad Maxwell, but to stabilise the title. With growth in sales in France, Germany, and Spain, the newspaper brought back Élan, its third section which had been suspended while the paper was losing £1 million a month. By the end of the year, the circulation appeared stable at 200,000.

As 1993 dragged on, however, the circulation dropped by at least 20,000. By August, fourteen members of staff were sacked and a plan was made to move The European into a more upmarket niche. A month later, Garside resigned and was replaced by the long-time managing editor Herbert Pearson. Pearson was immediately undermined when the Barclays’ managing director Greg MacLeod secretly prepared a magazine version of The European with a greater emphasis on features and analysis. The Barclay brothers, known for being hands-off proprietors, expressed little interest in the MacLeod project. MacLeod made his exit and Garside promptly returned as editor in June of 1994.

All continued as per usual until October 1996 when the Barclays appointed the former Sunday Times editor Andrew Neil as editor-in-chief of the Barclays’ three newspapers: The European and the two Scottish titles, The Scotsman and Scotland on Sunday, which they had bought a year before. Soon after, and surprisingly to the staff, Garside quit as European editor and Neil took over that responsibility too, with Herbert Pearson acting as the day-to-day head honcho. Andrew Neil brought new ideas to reinvigorate the paper but the perennial plan to turn upmarket finally materialized in 1997. The European was transformed into a high-end tabloid-sized colour magazine from June 1997 before it emerged in its final magazine form in March 1998.

But the Barclays were at the end of their tether. The European had lost £50 million since they took it over in 1992, and through the many trials and transformations its circulation failed to stabilise and continued its decline. By the middle of 1998, the Barclays threw in the towel and put The European, with Gerald Malone now at the editorial helm, up for sale. In September, it was announced that, unless a buyer was found, the paper would be wound down over the next ninety days. While there were hopes for an eleventh-hour savior in the form of Time Warner, and then Bloomberg, neither conglomerate made an offer. The final number of The European came out on December 14, 1998.

What then was the cause of The European‘s downfall? While it may seem strange that ‘Europe’s national newspaper’ faltered during the decade that witnessed the greatest leaps in European integration, the title was beset by such a multitude of problems from the very start that one might very well ask the question how it survived so long.

While undoubtedly the driving force behind The European, Robert Maxwell, with his erratic disposition, was a problem in and of himself. The unreliability of the paper’s circulation figures, actively fudged by ‘Captain Bob’, made advertisers think twice before investing part of their marketing budget. Maxwell’s problematic nature culminated in the massive financial scandal that rocked his empire, finalized by his mysterious death at sea. That the newspaper survived the death of its animating spirit so soon after its foundation is testament to the people who were determined to keep The European alive.

The commercial end of the newspaper’s operation was always a source of woe. Maxwell had been obsessed with newsstand circulation and so The European was one of the few newspapers that was actually more expensive to subscribe to than to buy from a newsagent — a factor which was unhelpful in building a loyal readership.

Starting a newspaper aimed at the middle-market at a time when that market is abandoning the printed media was doubtless an insolvable conundrum. The most obvious solution was to reorient the newspaper upmarket and find a suitable niche, but that too was already well taken care of by the Financial Times, the Economist, and the Wall Street Journal.

Distribution, meanwhile, was “an impenetrable mystery” according to Gerald Malone, the paper’s final editor. “I could never buy it in [the London Borough of] Wandsworth, but without fail found a copy in the village shop in Earlston, a tiny community in the Scottish Borders.”

Malone also claimed The European‘s staff was somewhat inconsistent in ardour. Mixed amongst the “hardworking young talent” and the “corps of professionals who brought the paper out through thick and thin” were “prima donnas” and “opinionated misfits past their sell-by date”. “In fact,” Malone wrote after the newspaper’s demise, “they were Fleet Street’s finest freeloaders: old-style fat-cats paid prodigious sums, in one case £75,000 for a three-day week”.

“One senior editor, who carped when I complained that the newsroom often resembled the aft deck of the Mary Celeste, resigned minutes before I could sack him, resenting my outrageous demand that he spend a bit more time in the office and forego long, boozy lunches fuelled with with Bulgarian wine.”

These practical problems aside, The European suffered a debilitating schizophrenia from birth. It claimed to be a European newspaper published in English but it was viewed more as a British newspaper reporting on European affairs. Maxwell’s stated aim (“Barking mad,” according to Malone) was to produce a newspaper for “the housewife in Toulouse”. But the Tolosanian housewife was already well catered for by the media of her own country, printed in her own language.

With institutional schizophrenia, a host of distribution problems, a staff of “freeloading prima donnas”, and the disappearance of its founder into the murky depths of the sea, it is indeed surprising that The European managed a good eight years in print. But besides all these there remained a never-solved existential dilemma at the heart of The European — “Europe’s national newspaper” — that it was impossible to be the national newspaper of a nation that doesn’t exist.

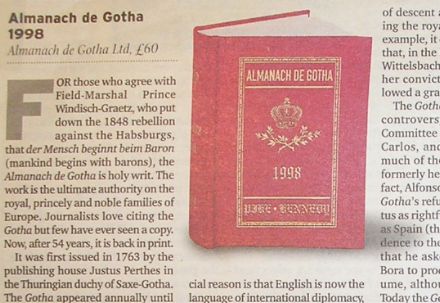

Warner on the Gotha

Whilst rummaging through my room at home in New York last week, I came across this article which I had cut out of the ill-fated European in 1998 written by none other than Mr. Gerald Warner, KM. I was fourteen years old in 1998 and the European folded about a year later. Click here to read in jpg form. (A large file, some browsers may require resizing to view the text at a readable size).

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Waarburg October 2, 2024

- A Prize for the General September 23, 2024

- Articles of Note: 17 September 2024 September 17, 2024

- Equality September 16, 2024

- Rough Notes of Kinderhook September 13, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories