South Africa

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The Rhodes Memorial

PERCHED AMID THE bluegum trees on the slopes of Devil’s Peak in Cape Town is the memorial to one of the most brilliant & cunning men the world has ever produced. Cecil John Rhodes may have been born in Bishop’s Stortford, England, but his worldly glories all emanated from the Cape of Good Hope, and so it’s appropriate that his memorial stands here in Cape Town. His first commercial enterprise in South Africa was founding the Rhodes Fruit Farms (now Rhodes Food Group) which still exist on the road from Stellenbosch to Franschhoek, and has since expanded throughout the Western Cape, and to the Transvaal and Swaziland. But it was his creation of the diamond monopoly De Beers out of the Kimberley mines that made him one of the wealthiest men in the world. Ten years after being elected to the Cape Parliament, he was made Prime Minister of the Cape in 1890, but his catastrophic and illegal attempt to seize the independent Transvaal in 1895 forced his resignation from politics in disgrace. (more…)

The Union Defence Force

From 1912 to 1957, South Africa’s military was called the Union Defence Force (the Union in question being the Union of South Africa, the other USA). The Nationalist government renamed it the South African Defence Force (Suid-Afrikaanse Weermag) in 1957, prior to the declaration of the Republic of South Africa in 1961. After the introduction of universal suffrage in 1994, the SADF was merged with the MK (Umkhonto we Sizwe, the ANC’s terror branch) and APLA (Azanian People’s Liberation Army, the terrorist wing of the Pan-Africanist Congress), as well as the Self-Protection Units of Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi’s Inkatha Freedom Party, into the South African National Defense Force (SANDF, or SANDEF), which remains the name of the country’s armed forces today.

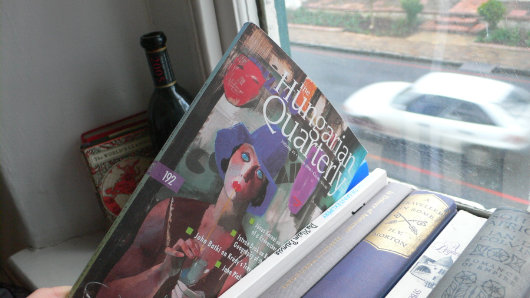

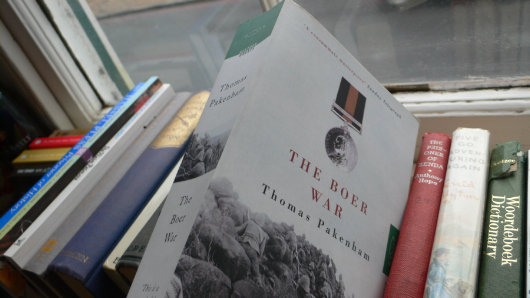

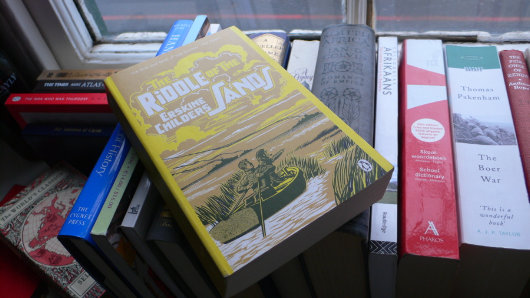

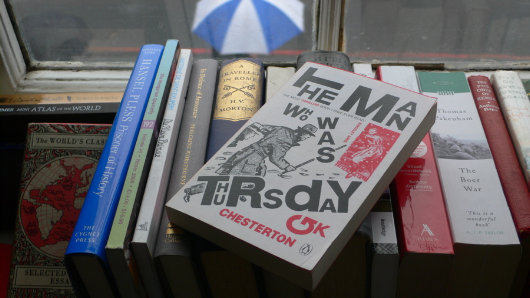

My bolt-hole in the Cape

Winter in the Western Cape is relatively mild: grey days of pouring rain when the clouds veil Stellenbosch mountain, coupled with beautiful sunny afternoons best spent having a coffee with a friend at a sidewalk cafe.

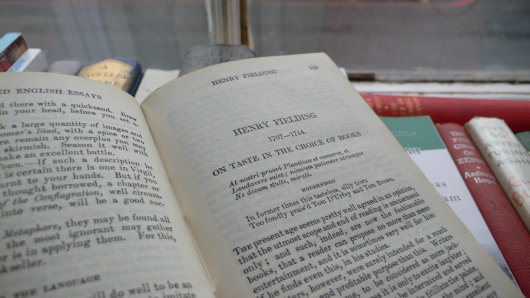

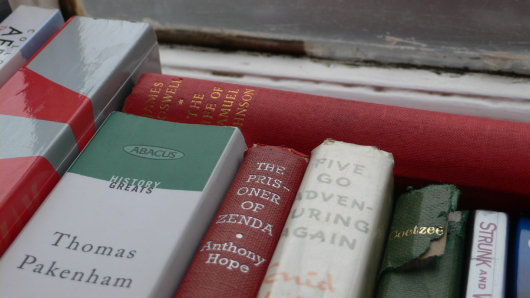

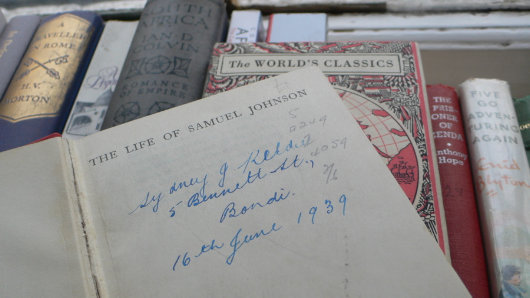

Today is one of the grey days, however, in which one hopes to leave the house as little as possible (provided, that is, one is already adequately supplied with enough tea and books to last the day).

My little flat is in an old Dutch townhouse in the middle of town, one which the arbitrary modernisers neglected to supply with an alternative source of heat when they foolishly removed the iron stoves and blocked all the fireplaces.

Nevermind. A good jumper and a cup of rooibos will keep me warm as I make progress with Sassoon’s Memoirs. (more…)

Braai at the Dutch House

THE CUSACKIAN DICTIONARY OF the English Language defines the word braai thusly: “braai; S.Afr. [Afrikaans, lit. ‘to grill’.] n. and v. trans. and intr.; An out-door meal at which meat is grilled by the heat emanating from the embers of burnt wood.” The uncultured observer, when informed of a braai, often incorrectly equates it with a barbecue. The chief difference between a barbecue and a braai is that a barbecue tends to use either propane gas or ready-made charcoals, while the laboursome but worthwhile burning of wood is necessary to a braai. (more…)

Leeuwenhof

One of the better aspects of the job of Premier of the Western Cape is Leeuwenhof, the official residence that comes with the job. The estate on the slopes of Table Mountain dates from the days of the Dutch East India Company. That renowned governor of old, Simon van der Stel (after whom both Simonstad & Stellenbosch are named), granted the land to Guillaum Heems, a free burgher, to ‘clear, plant, plough, develop and work’. Heems christened the land Leeuwenhof — “Lions Court” — but sold it just two years later to Heinrich Bernhard Oldenland, Master Gardener of the Company’s Garden and Superintendent of Works for the Dutch East India Company.

Oldenland died just a few months after purchasing Leeuwenhof, and it passed into the hands of the fiscal Blesius, whose widow’s death put the estate under a series of masters until it was sold it for 14,000 guilders to Johan Christiaan Brasler, a Dane. Brasler enjoyed a good many years there in prosperity of late-eighteenth-century Cape Town, a period when the building of stately homes, townhouses, and government buildings became (as Cornelis de Jong put it at the time) “a passion, a craziness, a contagious madness that has infected nearly everyone”. This was the age of Thibault, Anreith, and Schutte — the true golden age of Cape Town’s stately finery. Inspired by the “madness” of which De Jong tells, the Dane Brasler converted the humble farmhouse of Leeuwenhof into the dignified abode we know today. (more…)

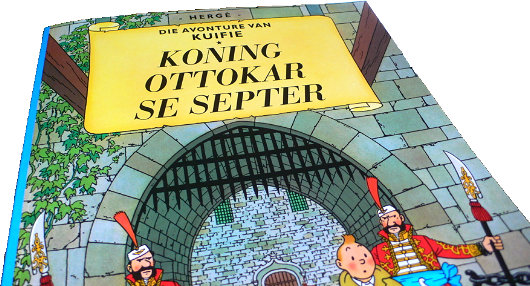

Die Koninkryk van die Swart Pelikaan

SYLDAVIA IS MY favourite country in the world. The buildings are old, the peasants are happy, and the king is ruling from his throne. Adding to my collection of Tintin books, the preponderance of which remain in New York, I know have three Afrikaans editions of Hergé’s works: Die Blou Lotus, Die Geheim van ‘De Eenhoorn’, and — my preferred among all the Tintin books — Koning Ottokar se Septer. Aside from Afrikaans, the rest of my copies are all either in French or English. I have a copy of the reprinted Tintin au Pays des Soviets and I just recently bought a copy of Tintin in the Congo, as I figured the European Union’s attempt to ban the book might make it harder to come by in years to come. I bought a copy of Le Sceptre d’Ottokar in a gas station in Brittany, one of the six special editions with a preface by Bernard Tordeur of the Hergé Foundation released in 1999/2000. Aside from Au Pays des Soviets & Le Sceptre, the only other French editions I have are L’Île Noire and Le Lotus bleu. (more…)

The Principality of South Africa

“… or some such thing.”

History has shown that good ideas often come from the humblest of sources. One such example, though regrettably one of a suggestion not put into practice, was a proposal submitted by D. M. Perceval, the humble clerk of the Advisory Council of the Cape of Good Hope colony in 1827 to his higher-ups in the Colonial Office in London. Perceval wrote to request an official seal for the British colony at the end of Africa, but he went a step further with his fairly normal request, extraordinarily suggesting that “the opportunity might be taken to erect [the Cape of Good Hope] into the Principality of South Africa, or some such thing, for the present name is really too absurd for the whole country.”

The title “Prince of South Africa” would have been part of the British Crown, and presumably available as a courtesy title for offspring, just as the eldest son is often (such as now) created Prince of Wales. Would the second son then be “Prince of South Africa”, or would the title stay with the Sovereign? “By the grace of God, King of Great Britain & Ireland, Emperor of India, Prince of South Africa, &c.” It does have a nice ring to it. (more…)

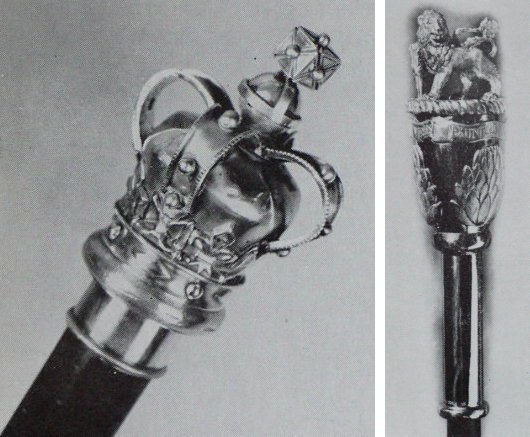

Black Rod — Swart Roede

In my post on the 1947 Royal Visit to Cape Town, I mentioned just in passing the title of the Draer van Swart Roede — or the Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod, as he is known in English. Well, here is the Black Rod itself. The original South African Black Rod (left) dates from the Parliament of the Cape of Good Hope and was adopted as the Black Rod of the Union Parliament when South Africa was unified in 1910. After the abolition of the monarchy in 1961, a new Black Rod (right) was commissioned which featured protea flowers topped with the Lion crest from the South African coat of arms.

Black Rod (the person, not the staff) was the Senate’s equivalent of the House of Assembly’s sergeant-at-arms (ampswag). The first Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod in history was appointed in 1350 and the position still exists today in the British Parliament of today. Black Rod is sergeant-of-arms of the House of Lords, as well as Keeper of the Doors. The Usher’s best-known role is having the doors of the House of Commons ceremonially slammed in his face when he acts as the Crown’s messenger during each State Opening of Parliament, a ritual derived from the 1642 attempt of Charles I to arrest five members of parliament.

In South Africa, die Swart Roede traditionally wore wore a black two- or three-pointed cocked hat, a black cut-away tunic, knee breeches, silk stockings and silver-buckled shoes, but this costume of office has undergone a process of modernisation since the 1950s. After the vast expansion of the electorate in 1994 and introduction of an interim constitution, Black Rod’s title was officially shortened to “Usher of the Black Rod” to make it “gender-neutral”. (Regrettably, the Canadian Senate has also mimicked this innovation, though it is often unofficially ignored.) When a new, permanent constitution was enacted in 1997, the Senate was replaced by the National Council of Provinces as the upper house of parliament. A new Black Rod (the staff, not the person) was introduced in 2005, but is of such a garish design that it is best left uncommented upon.

The Band-leader & the Sergeant-Major

I came across these two characters in the Castle in Cape Town, the oldest building in South Africa and still home to the Cape Town Highlanders and Cape Garrison Artillery.

A Good Day in Cape Town

The South African Royal Family’s 1947 visit to “Die Moederstad”

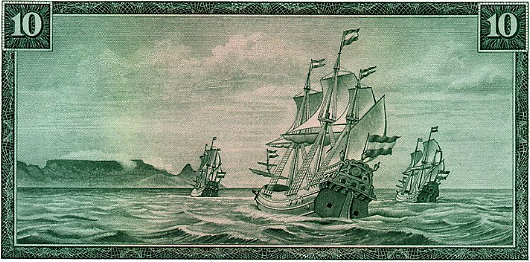

SOUTH AFRICA IS a nation that took a long time birthing, from the first steps van Riebeeck took on the sands of Table Bay in 1652, through the tumult of the native wars, the tremendous conflict between Briton & Boer, and ultimately what was hoped would be the final reconciliation in Union of South Africa — 1910. In that year, young Prince Albert of York & of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha was just fifteen years of age, and South Africa became a dominion just weeks after his father became King George V.

Albert was the second son of a second son, so at the time of his birth (and for most of his early life) it was never expected that he would one day be King of Great Britain, Emperor of India. It was his brother’s abdication that thrust poor Bertie, as he was always known to his loved ones, upon the throne imperial. It was a cold December day in 1936 that the heralds of the Court of St. James proclaimed him George VI.

By his nature, the King was a quiet and reserved man, partly because of the stammer that impeded his speech. George VI was happiest among his family, and they accompanied him in 1947 on a long voyage aboard HMS Vanguard, to his far-off kingdom on the other side of the world, where the two oceans meet. It was the first time a reigning monarch has set foot on South African soil, and Capetonians waited in earnest anticipation to see their sovereign. How appropriate that this happy city — moederstad, or “mother-city”, of all South Africa — would be the first to receive him. (more…)

The Goerke House, Lüderitz

THE FAMILIAR PHRASE has a person in difficult circumstances being “between a rock and a hard place”. The Namibian town of Lüderitz is stuck between the dry sands of the desert and salt water of the South Atlantic — this is the only country whose drinking water is 100% recycled. Life in this almost-pleasant German colonial outpost on the most inhospitable coast in the world has always been something of a difficulty, but the allure of diamonds has at least made it profitable. One such adventurer who came from afar and made his fortune in this outer limit of the Teutonic domains was one Hans Goerke. (more…)

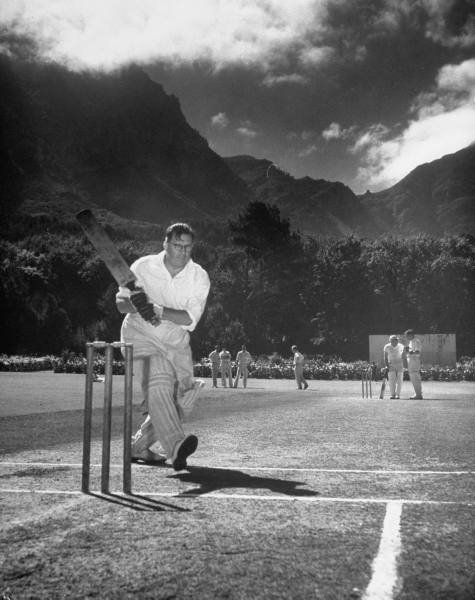

Minister van krieket

The Minister of the Interior, Mr. Theophilus Ebenhaezer Dönges, practises his swing while playing for the National Party cricket team.

The Huguenot Monument, Franschhoek

AMONG THE MANY peoples who, through the various vicissitudes of history, have found their home in South Africa are the Huguenots, or French Protestants. These people have always had a certain fascination for me, having being born so close to New Rochelle, the city in the New World founded by Huguenot refugees. The city’s public high school is a rather stately French neo-gothic chateau in the middle of Huguenot Park.

My own alma mater — a smaller private school in New Rochelle — counted Huguenot descendants among its first students and there was at least one remaining in my own school days. Street names such as Flandreau, Faneuil, and Coligni betray the French heritage of the city’s founders, and Trinity Church still has the old communion table brought over from La Rochelle. (more…)

The eternal specter of the National Party

Above: Irish journalist Fergal Keane interviews a poor black South African.

This recent general election in South Africa marked the first time since 1910 — the year the country was unified as an independent dominion — that voters weren’t given the option of voting for the Nationalists. The party was founded in time for the 1914 election, and first entered government in coalition with the Labour party in 1924, but their most famous victory was in the general election of 1948. It was then that they won an outright majority and introduced the ideology of apartheid. The famous Brazilian counter-revolutionary Dr. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira was of the opinion that South Africa had been in the process of developing a genuinely feudal society until the introduction of apartheid put a full-stop to this evolution.

Evil and heretical though apartheid was, such are the wounded and fearful hearts of men that it won for the National Party each successive general election until the introduction of universal suffrage in 1994. Admittedly, a large proportion of the Nationalist vote was not necessarily a vote for apartheid but instead a vote against communism. Soviet-backed communist subversion escalated sharply throughout Africa in the 1950s, especially as Nelson Mandela launched his internal coup taking over the previously broad-based & non-violent African National Congress and transforming that body into an officially and openly Soviet-aligned group with a terrorist wing whose activities rightly landed him in jail.

With the end of apartheid, the Nationalists had to contend with a universal adult electorate of every South African over eighteen years of age. In 1989, the last election under apartheid, over 2,000,000 whites, 261,000 coloureds (mixed-race people), and 154,000 Indians took advantage of their right to vote. In 1994, meanwhile, over 19.5 million voted. Most interestingly, the votes of the (mostly Afrikaans-speaking) coloured population — whose right to vote was taken away by the Nationalists in the 1950s before being quasi-reintroduced in 1984 — turned around and voted for the National Party en masse, out of fear for the behemoth of the black-dominated ANC.

The party still came second in the 1994 election with 20% of the vote — a respectable result considering the massive media push supporting Mandela & the ANC. But the National Party refused to take advantage of their showing. Under their supremely naïve leader, F. W. de Klerk, instead of forming a noticeable opposition to the ANC behemoth and thus laying the foundations for a robust tradition of antagonistic government and opposition debating eachother, the Nationalists did the worse thing imagineable and actually joined the government (as did the leaders of the black-conservative Inkatha Freedom Party). Had the Nationalists & Inkatha joined forces then as a united multi-racial moderate conservative opposition to the ANC, South Africa’s democracy would be in a much healthier state than it is today. Instead, they chose the gravy train and the voters have punished them in every subsequent election.

For their sins of opportunism, the Nationalists were rightly abandoned by voters and eventually the party dissolved itself and more-or-lessed merged into the ANC they had spent decades proclaiming the dangers of. Marthinus van Schalkwyk, the last leader of the Nationalists, is today an ANC member and cabinet minister. (Here I must concede that he is actually quite a capable minister and was a very sound conservationist as Minister for the Environment; his current portfolio is Tourism).

So April 2009 was the first general election since the dissolution of the National Party. F. W. de Klerk cast his vote in front of the news cameras and refused to divulge which of the parties got his vote, except that it was for an opposition party. Nonetheless, there were a number of eccentric parties which positioned themselves as new-born versions of the Nationalists. One, founded by a known charlatan and fraudster, actually claimed the name “National Party” and was quite multi-racial in its composition with a broadly populist agenda. Another, the “National Alliance“, was a primarily coloured group based in the Northern Cape. Both, however, used variants of the sun logo employed by the old Nationalists. How did they do? Well, rather predictably, convincing voters to back a party whose two best-known polices are first, apartheid, and second, sucking up to the ANC, was not an easy task. Both parties of a neo-Nat persuasion failed miserably, and I think it’s safe to say we’ll hear little of them again.

Still, the National Party’s forty-six straight years in power obviously impacted the history of this country, and their legacy lurks like a specter in the back of the minds of many. Eccentrics who try to resurrect this dead corpse, however, will swiftly be relegated to the cabinet of curiosities.

« Kampusquote »

Many college newspapers have their “overheard” sections, in which they give a selection of amusing or stupid things said around town. Our paper, Die Matie, has “Kampusquote”, the latest installment of which featured this nugget:

“Just make sure you don’t mix your white and black clothes!”

Alright, it sounds better in Afrikaans. Another favourite of mine was:

— Student upon learning that the head of the Music Conservatory is rotated amongst the conservatory’s departmental chairs

Zuma’s Day

“PRAETORIA PHILADELPHIA” — Pretoria of Brotherly Love — was the formal name for the paramount of South Africa’s three capital cities. Pretoria, the jacarandastad, is home to the Executive; Cape Town, die moederstad, is home to the Parliament, and Bloemfontein, the “City of Roses”, is home to the High Court of Appeal. While the politics of government take place in Cape Town, its actual administration takes place in Pretoria, and all that flows forth from the stately Union Buildings that preside over the city from atop Meintjieskop. The Uniegebou is composed of two wings that come together in a semicircular amphiteatre, symbolizing the coming-together of Briton & Boer in the Union of South Africa. Designed by Sir Herbert Baker, Lutyens’ lieutenant in the building of New Delhi, some believe it to be his finest work.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories