Scotland

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The Spott Estate, Dunbar

HERE IS A lordly demesne! In East Lothian, thirty-one miles from the centre of Edinburgh and three from the Royal Burgh of Dunbar, sits the Spott House and estate, now on the market from Knight Frank. The property is a whopping 2,463 acres in total, including 1,779 acres of arable land, 214 of pasture, and 356 acres of woodland. The estate has more than quadrupled in size in the past decade, under the ownership of the Danish-born Lars Foghsgaard, who bought just 600 acres in the year 2000.

As The Times wrote of Mr. Foghsgaard, “Clad in tweed jacket, plus fours and Hunter wellingtons, with several brace of partridge in his hand and his labrador at his side, he looks the very image of the country gentleman as he strides though his East Lothian estate.”

“The previous owner was very involved in the land,” Mr. Foghsgaard told the Times. “I am not a farmer, so I employed a farm manager: it’s crucial to have the necessary skills and connections in the area to do the job well, and as a foreigner I did not have those.” But the Dane does enjoy seeing the workings of the farm. “When I walk the dog, I always pass through the cowshed, where we have lambs being born each day — it’s such a joy to see.” (more…)

Preservation is Not Enough

A Proposal for Enhancement

IT IS COMMONLY said of St Andrews that it is a place of beauty. This is often a compliment to its natural setting, with open skies arcing over the reaches of the bay, and ancient rock and cliff yielding to the changing rhythms of the waves. At the same time visitors are generally struck by the pleasing combination of natural and built environments: the ruined grandeur of the Cathedral and Priory standing bare to the elements; crowstep-gabled cottages gathered in against the wind; the broad thoroughfares interlinked with narrow cobbled lanes; and the church towers etched against the sky. There is also the scholarly dignity of Deans Court, the quizzical posture of the Roundel, the charm of the courtyards to the south of South Street, the sad ruination of Blackfriars juxtaposed with the aspiring frontage of Madras College, and other evocative sights besides.

Here and there within the midst of all of this stands, physically, historically, and socially, the University. Its contributions to the architectural distinction of the old town are obvious enough. They are, principally, the harmonious South Street complex of St Mary’s College (1593-41) to the west, Parliament Hall (1612-43) to the north, and the Library extension (1889-1959) – now the Psychology wing – to the east; and the North Street set of the Collegiate Church of St Salvator, Gate Tower and tenement (1450-60), and beyond it the west block (1683-90) containing the Hebdomadar’s Room, and to the east and north the College buildings (1829-31 and 1845-6, respectively). There are other smaller and oft-reworked jewels associated within the University: St John’s House in South Street (15th, 17th, 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries), St Leonard’s Chapel (remodelled c. 1512), and the ‘Admirable Crichton’s House’ (16th century), but the principal architectural benefactions of the University to the town are the North and South Street college complexes. I have not mentioned the Younger Graduation Hall (1923-9) and the Student Union (1972) and prefer to leave it for readers to determine what might be said of these.

It could hardly have passed unnoticed that the list of contributions dates mostly from the late middle-ages to the nineteenth century, and this fact raises two questions: first, whether in the second half of the twentieth century the University was sufficiently attentive to its role as principal architectural patron; and second, how it might now hope to enhance the built environment of St Andrews. (more…)

The Daisy Wheel

Among the most well-known works of modern Scottish design, besides the ‘Clootie Dumpling’ of the Scottish National Party, there is the logo of the Royal Bank of Scotland: the Daisy Wheel. Now one of the most well-known financial brands in the world, the Royal Bank of Scotland was founded in Edinburgh in 1727, thirty-two years after its rival, the Bank of Scotland. (The Bank of Scotland, as it happens, was founded by an Englishman, John Holland — just as the Bank of England was founded by a Scot, Sir William Paterson).

The Scottish Parliament had declared in 1689 that King James VII had, by his absence, forfeited the throne, and handed the Crown to his Dutch rival William of Orange, who had already seized the throne in England. The House of Hanover succeeded to the throne of the new United Kingdom which had been created in 1707, but the Bank of Scotland was suspected of harbouring Jacobite sympathies. The London government was keen to help out Scottish merchants loyal to the Hanoverians and so, in 1727, King George granted a royal charter to the new Royal Bank of Scotland. (more…)

The East Neuk of Fife

THE  EAST NEUK of Fife is one of my favourite little corners of the globe, in what is definitely my favourite country in the world. Here are a set of almost unspoilt little fishing villages with a quite localised architectural style that makes them instantly recognisable. The name of this little regionlet signifies its location as the east ‘nook’ of the Kingdom of Fife, that juts out into the North Sea.

EAST NEUK of Fife is one of my favourite little corners of the globe, in what is definitely my favourite country in the world. Here are a set of almost unspoilt little fishing villages with a quite localised architectural style that makes them instantly recognisable. The name of this little regionlet signifies its location as the east ‘nook’ of the Kingdom of Fife, that juts out into the North Sea.

Those concerned for this part of the world might be interested in signing up for the East Neuk of Fife Preservation Society, which has completed admirable work all over the East Neuk, and is currently considering the restoration of the gatehouse of Pittenweem Priory.

Interesting Things Elsewhere

Benedict and Britain

The papal visit began in Scotland, and the smaller setting (Scotland has just five million people, fewer than London alone) proved a wiser starting point of the pontiff’s trip to Great Britain. “Would the first day have been the success it was if it had taken place in England?” asked William Oddie. “Would the papal chemistry have worked so soon in London, that vast and engulfing megalopolis, if the reception by Her Majesty had taken place in the impersonal splendours of Buckingham palace rather than in that ancient architectural wonder Holyrood house (whose very stones are a testimony to its Catholic origins) and if the Popemobile ride through the streets afterwards had been down the Mall?”

Damian Thompson has argued that the papal visit has proved a triumph for Benedict and a humiliation for the secular-humanist crowd. The Daily Telegraph blogs editor and Catholic Herald editor-in-chief says that the Pope’s natural shyness has worked to his advantage, while the former Spectator editor Dominic Lawson argued in the Independent that Benedict’s unpolitical nature gives him a popular appeal.

The volume and biliousness of the media’s campaign against Benedict XVI has actually backfired and turned the lukewarm into pope-welcomers (like Kate Hoey MP, reports Christina Odone). Another blogger reported the influence a television programme produced by the gay activist and sometime paedophilia sympathiser Peter Tatchell that was broadcast just before the Pope’s arrival:

‘Are you going tomorrow?’ I asked. ‘Yes, I am,’ she replied. ‘I wasn’t going to at first, because it’s a long day, but when I saw that rubbish last night on the telly, I changed my mind. I’m don’t care if I die there; I’m going.’

Meanwhile Mark Dowd, another homosexual, was determined to be even-handed in his documentary “Benedict: Trials of a Pope”, and his broadcast was well-received. The filmmaker wrote in the Catholic Herald “when you have to make a one-hour programme on one of the most clever and gifted people on the planet you have to look behind the headlines and the angry rants on the blogosphere. In short, you have to do justice to the man as best as you can.”

Hilary White had a chat with barrister and Catholic Union chairman Jamie Bogle, who argued that the visit has taken the wind out of the sails of Benedict’s enemies.

“Jamie also pointed out that the protesters were having a bit of fun with the numbers,” Hilary writes. “A friend in Vancouver said that 25,000 turned out for the demonstration. The National Secular Society said it was ‘between 10 and 12,000’. But Jamie told me he had spoken with some of the cops present, and they said it was no more than 2,000.”

It was like a scene from 1984

Atheist Brendan O’Neill reported being disturbed by the anti-papal demonstrators, reporting that there is “a sharp authoritarian edge” to the radical pope-haters. “Things turned ugly outside Downing Street when Terry Sanderson of the National Secular Society branded the pope an ‘enemy of the state’, giving rise to the cacophonous chant: ‘GO HOME POPE, GO HOME POPE.’ It was like a scene from 1984. I have been on many a radical demo that has challenged the branding of some group or individual as ‘enemies of the state’; but this is the first radical demo I’ve been on where the protesters themselves demanded the silencing and even expulsion from Britain of someone they decreed to be an ‘enemy of the state’. Even one-time ‘enemies of the state’ – the so-called queers and the old left – were using that criminalising phrase, that piece of political demonology, to chastise the pope. It was the world turned utterly upside down.”read more

Also: The campaigners against the pope’s visit have more in common with the fanatical Inquisitors of old than with Enlightened liberal humanists, says Frank Furedi.

The conservative case for rail

File this one under “things we always knew and are glad someone agrees”: the dissident conservative fortnightly The American Conservative presents a symposium of articles about getting the USA back on the rails. William Lind attempts to destroy the myth of public-transport-hating conservatives while attacking the rampant subsidisation of federal highways. Former Milwaukee mayor John Norquist says the Right shouldn’t surrender the cities to the Left. Glen Bottoms does the numbers on the return to rail and tries to figure out how much it will cost. Finally, John Robert Smith argues that there’s still some life in America’s Main Streets. Christopher Leinberger discusses how private development can fund public infrastructure. read more

The Thomist constitution

St. Thomas Aquinas, the “Dumb Ox”, stated that “all should take some share in the government: for this form of constitution ensures peace among the people, commends itself to all, and is most enduring”. Aelianus muses on a Thomistic view of government, explores the pros and cons of monarchy, aristocracy, democracy, and ponders the political position of the family in society. read more

Swedish under threat in Finland

Swedish was historically the language of Finland’s nobility and intelligentsia, as well as of the country’s ethnic Swedish minority — Finland’s first president and greatest hero, Field Marshal Mannerheim, could barely even speak Finnish. But while the Scandinavian land is still officially bilingual in education and government, the 5.5% of the population who are Swedish-Finns is increasingly viewed as “the world’s most pampered minority”. read more

The Südtirol success story

Amid the warnings of doom and gloom ahead for the Italian economy, one province has almost full employment and a healthy economy, not to mention a governor who has ruled for over twenty years. “We are living in the promised land,” — Südtirol. read more

The Highest Order in the Land

The Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle

In  accordance with tradition, knights are appointed to the Order of the Thistle on the feast of Scotland’s patron saint, the Apostle Andrew, but they are not formally installed until the following summer when the Queen is in residence at the Palace of Holyroodhouse. And so this past July, the ‘Thistle Service’ took place at St. Giles’, the High Kirk of Edinburgh, and two new knights were inducted into Scotland’s highest honour and most exalted order of chivalry.

accordance with tradition, knights are appointed to the Order of the Thistle on the feast of Scotland’s patron saint, the Apostle Andrew, but they are not formally installed until the following summer when the Queen is in residence at the Palace of Holyroodhouse. And so this past July, the ‘Thistle Service’ took place at St. Giles’, the High Kirk of Edinburgh, and two new knights were inducted into Scotland’s highest honour and most exalted order of chivalry.

The knights, dames, and officers, dressed in their flowing velvet mantles of green along with their hats and collars, gather across Parliament Square in the Library of the Society of Writers to Her Majesty’s Signet (Scotland’s professional body of solicitors), part of the Parliament House complex that long ago housed the kingdom’s legislature, and is now home to her courts. In Parliament Square itself, the Royal Company of Archers (the Queen’s Body Guard for Scotland) forms a guard of honour and is accompanied by the band of the Royal Regiment of Scotland. (more…)

dot Scot

Since  the decision by ICANN, the mysterious council of elders whose nomenclatory dominion spans, it seems, the entirety of the “world wide web”, to designate .cat as the “sponsored Top-Level Domain” of the Catalonian linguistic and cultural community, much speculation has arisen in various sub-statal lands throughout the world about future TLDs. In our favoured realm of Scotland, a campaign has arisen for .scot to be designated the TLD for Scotland. While I wholeheartedly support the campaign for a Scottish TLD, I have already expressed my reservations about the increasing size (not number) of TLDs. The traditional country-code TLDs are all two-letter combinations, and any new TLDs representing geographic entities ought to stick to this restraint.

the decision by ICANN, the mysterious council of elders whose nomenclatory dominion spans, it seems, the entirety of the “world wide web”, to designate .cat as the “sponsored Top-Level Domain” of the Catalonian linguistic and cultural community, much speculation has arisen in various sub-statal lands throughout the world about future TLDs. In our favoured realm of Scotland, a campaign has arisen for .scot to be designated the TLD for Scotland. While I wholeheartedly support the campaign for a Scottish TLD, I have already expressed my reservations about the increasing size (not number) of TLDs. The traditional country-code TLDs are all two-letter combinations, and any new TLDs representing geographic entities ought to stick to this restraint.

But then what would Scotland’s top-level domain be? .sl is taken by Sierra Leone, while .sc belongs to the Seychelles, and .st to São Tomé. We might hark back to the Gaelic with .al for Alba, except that it’s already occupied by Albania. Ah! Caledonia! How about .cd? Nope, that belongs to the Congo. Blast. It might be necessary to go to three letters then, which brings us either to .sco or .sct. Neither look all that attractive, though .sco has the advantage of being pronounceable. Actually, .sco is quite imaginable, when spoken: parliament.gov.sco, fifeherald.sco, glenfiddich.sco. It just doesn’t look right. .scot looks better, but the rhyming nature of “dot scot” is irritating to say aloud.

I do wish they’d make .gb available again. I’d much rather be a “gee-bee” than a “yoo-kay”. Great Britain is a natural entity, after all, whereas the United Kingdom is a government construct. Perhaps if the Union is re-negotiated, we might move from .uk to .gb, just as .yu was changed to .cs when Yugoslavia was renamed Serbia & Montenegro. (The two split not long afterwards, and went for .rs and .me).

With four letters, at least .scot is not the longest proposed top-level domain. Some ninny thinks there should be a .quebec — how cumbersome! .qu would be much better, and one can just imagine the Québécois pronouncing it. Other British proposals include .eng for England and .cym for Wales. “Norn Iron” loses out, as .ni belongs to Nicaragua, but .ul or .uls are conceivable for Ulster. Perhaps the Vatican could dole out .sre — Sancta Romana Ecclesia — for ecclesiastical domains.

Modern Scottish Architecture

Sydney Mitchell’s Royal Bank of Scotland, Kyle of Lochalsh

Among the surprisingly large pool of under-appreciated Scottish architects is Arthur George Sydney Mitchell. His Edinbornian works include Well Court in Dean Village, Ramsay Gardens in the Old Town, and his restoration of the Mercat Cross on the Royal Mile. Sydney Mitchell also did a number of branch commissions for the Commercial Bank of Scotland (which in 1959 merged with the National Bank to form the National Commercial Bank, which in turn merged into the Royal Bank of Scotland in 1979). (more…)

Alexander Stoddart: “An Elite for All”

Scotland’s national newspaper interviews Scotland’s national sculptor

By SUSAN MANSFIELD

The Scotsman | 22 November 2008

ALEXANDER STODDART welcomes me into his studio, and into the 19th century. “It hasn’t gone away, you see,” he says, brightly. “The 19th century is not a period in time, it’s a state of mind.”

Indeed, if one could visit the workshop of one of the great monumentalists of a century ago, it might look a lot like this: plaster casts in various stages of assembly; imperious figures missing limbs or, occasionally, a head; bags of clay which until recently were a working model of physicist James Clerk Maxwell.

Stoddart is Scotland’s premier neo-classical sculptor, the man who made the figures of Adam Smith and David Hume for Edinburgh’s Royal Mile, Robert Burns for Kilmarnock, the beautiful Robert Louis Stevenson memorial on the capital’s Corstorphine Road. He’s 49, but looks boyish, with his sandy hair and dusty lab coat cut off at the elbows. He is a man of swift, enthusiastic intelligence, rarely still, and almost never silent.

Despite once being dismissed by the Scottish Arts Council as “backward-looking, historicist and not reflecting contemporary trends”, Stoddart is busy. Around us are the plastercasts of past commissions: immense allegorical figures for the £6 million Millennium Arch in Atlanta, Georgia; religious commissions for a mysterious private client who has her own chapel “somewhere in North Britain”; parts of 70ft frieze for Buckingham Palace. A bust of Pope John Paul II for a Chicago seminary.

Soon they will be joined by James Clerk Maxwell, whose statue, commissioned by the Royal Society of Edinburgh, will be unveiled on Tuesday at the East End of Edinburgh’s George Street. Stoddart is thrilled to be sharing a street with 19th-century sculptural greats like John Steel’s Thomas Chalmers. “It’s the greatest honour to be anywhere near the company of Steel.”

And he is ready and waiting for the next question, the one about relevance. (more…)

A Palace on Princes Street

The North British & Mercantile Insurance Company, No. 64 Princes Street

PRINCES STREET IS the thoroughfare of the nation, and its sad decline during the second half of the twentieth century and only partial comeback since then are reflective of Scotland itself. The architects of Edinburgh’s New Town had no idea that Princes Street would evolve into a commercial avenue, and the street was originally laid out as a handsome row of Georgian townhouses, built between 1765 and 1800, facing Princes Street Gardens and the Old Town above behind them.

Almost immediately the mercantile and social nature of the street began to assert itself, with shops and traders setting themselves up in the converted basements and ground floors of townhouses. The New Club showed up at No. 86 Princes Street in 1837, coming from previous premises in St. Andrew’s Square and before that Shakespeare Square (where the former G.P.O. now stands).

As the Victorian era progressed, more and more of the Georgian townhouses were demolished and replaced with new buildings in the varying styles of age. It was just two years after Victoria’s death that an old company built a new headquarters in a brimming Edwardian baroque: the North British and Mercantile Insurance Company. (more…)

Our Cardinal Strikes Again

Cardinal O’Brien, Scottish Primate, Preaches at Newly Ordained Priest’s First Mass in the Extraordinary Form at St. Mary’s Cathedral Edinburgh

Keith Patrick O’Brien, the Primate of Scotland and Cardinal Archbishop of St Andrews & Edinburgh, this weekend preached at the first mass offered by the recently ordained Fr. Simon Harkins of the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter. The mass was offered in the Cardinal’s own Cathedral of St. Mary in Edinburgh, Fr. Harkins’s own home town. The Very Rev. Fr Josef Bisig FSSP and the Very Rev. Fr. Franz-Karl Banauch FSSP assisted, and monks from the Transalpine Redemptorists of Papa Stronsay (who provided these photos) were also present, in addition to a number of diocesan priests.

I’ve spent the past eight years of my life divided between three (arch-) dioceses and I have to admit that Cardinal O’Brien is still the one I feel the greatest affection for. He’s an affable, uncomplicated fellow, and can be relied upon to defend what’s right in the media — unquestionably one of the best prelates in Britain today.

“I find him a much more approachable figure than other Scots prelates,” writes Damian Thompson, “less inclined to stand on his dignity despite (or perhaps because of) his red hat. I met him once at a party to relaunch the Scottish Catholic Observer, to whom he’s been a good friend; he didn’t sweep in surrounded by flunkeys, but hung around chatting in ordinary priest’s dress, reminding me a bit of Basil Hume in that respect.”

As it happens, I’m head of Cardinal O’Brien’s fan club on Facebook, which I encourage any Facebook users out there to join.

God bless our cardinal, and many congratulations to Fr. Hawkins! (more…)

The Presiding Officer’s Gown

While the  Westminster Parliament has a Speaker, the Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh has a “Presiding Officer” — a rather dull title if you ask me. The auld Estaits of Parliament abolished in 1707 were headed by the Lord Chancellor of Scotland, an office which fell into abeyance shortly after the Act of Union.

Westminster Parliament has a Speaker, the Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh has a “Presiding Officer” — a rather dull title if you ask me. The auld Estaits of Parliament abolished in 1707 were headed by the Lord Chancellor of Scotland, an office which fell into abeyance shortly after the Act of Union.

When the “Scottish Parliament” was refounded in 1997, the first man to hold the new job of Presiding Officer was Sir David Steel (the Rt. Hon. the Lord Steel of Aikwood), the despicable creature who as an MP introduced legal abortion to the United Kingdom in 1967, and who has inexplicably and disgracefully been created a Knight of the Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle, the highest honour in the land (the Scottish equivalent of England’s Garter).

Anyhow, the St Andrews Fund for Scots Heraldry decided to commemorate the hosting of the Heraldic & Genealogical Congress in Scotland by commissioning a ceremonial gown for the Presiding Officer of the Scottish Parliament, who lacked one at the time. This rather handsome creation was presented to George Reid, the holder of the office at that time, during 27th International Congress of Genealogical and Heraldic Sciences held at St Andrews in 2006. Unfortunately I can find no evidence that this well-executed gown has ever been used. (more…)

A New Scots Town in the Highlands

The 20th Earl of Moray teams up with Miami-based firm Duany Plater-Zyberk to plant a New Town of 10,000 inhabitants outside Inverness

BELEIVE IT OR not, Inverness is one of the fastest-growing cities in Europe, and a local landowner, the 20th Earl of Moray, has teamed up with Duany Plater-Zyberk, an American firm known for its traditional architecture and urbanist ideas, to help create a sustainable new town of 10,000 inhabitants near the “Capital of the Highlands”. Tornagrain will rest on a 200-hectare (500-acre) site on the A96 corridor between Inverness and Nairn. Much of the recent growth in the Highlands has been poorly managed, raising concerns of suburban sprawl and poor land management. Moray Estates, the land holding company of the Earl of Moray (pronounced ‘Murry’) has decided to take the lead by planning a new town in the best tradition of Scottish architecture and urban development. (more…)

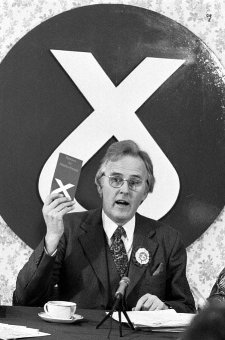

The Clootie Dumpling

IT IS A DESIGN masterstroke, combining simplicity and ease of recognition with layers of symbolism. The emblem of the Scottish National Party is just one single line that descends, turns around, and crosses itself, but while remaining uncomplicated manages to evoke the Saltire (Scotland’s flag), the thistle (Scotland’s flower), and — the pudding which has given the logo its nickname — the clootie dumpling, a Scots specialty. And yet, despite its ubiquity, there is surprisingly little to be found online about the history of the SNP’s clootie dumpling.

IT IS A DESIGN masterstroke, combining simplicity and ease of recognition with layers of symbolism. The emblem of the Scottish National Party is just one single line that descends, turns around, and crosses itself, but while remaining uncomplicated manages to evoke the Saltire (Scotland’s flag), the thistle (Scotland’s flower), and — the pudding which has given the logo its nickname — the clootie dumpling, a Scots specialty. And yet, despite its ubiquity, there is surprisingly little to be found online about the history of the SNP’s clootie dumpling.

The emblem was commissioned by William Wolfe (right) in 1962 for the parliamentary by-election in which he was standing as the Scottish Nationalist candidate. The party had typically employed a lion rampant as its symbol, which Wolfe thought too complex, and got Julian Gibb (in his own words, “scarcely out of childhood”) to design the brilliantly simple logo. “A political visionary with an eye for iconography,” according to Gibb, Wolfe used the emblem in the unsuccessful by-election campaign and a year later successfully proposed it to the party for adoption as the party emblem.

“The adoption of a geometric logotype is a bold act for a political organisation, especially a nationalist one, with the swastika a not too distant memory,” writes Gibb. “But the inner logic of the thing was persuasive. Forbye imagined allusions to saltire, thistle, and clootie dumpling, there was perhaps something irresistible about virile angularity supported on swelling curvature, implying among other things that in this outfit, the mechanistic depended on the organic. At one end of the scale of application it was devised to be hastily slapped on walls with a furtively loaded brush (the aerosol age had yet to come) and a quick flick of the wrist – no skill required. Try doing that with the lion rampant.” (more…)

‘Love over Parliament House’

Persuant to our discussion regarding Scotland’s three parliament buildings, Scots Law News reports that the Caledonian scribe Alexander McCall Smith has been called to the Scots bar.

Scotland’s Three Parliaments

All of Them More Beautiful than the Current Parliament Building

IT IS ONE OF those curious aspects of Edinburgh: its multiplicity of parliament buildings. The Estaits of Parliament, as they were known in the old days — consisting of the three estates of prelates, lairds, and burghers — first met in the Great Hall of Edinburgh Castle in 1140, though the first gathering of which we have primary source material was at Kirkliston in 1235, during the reign of Alexander II. The body led a somewhat peripatetic existence, meeting wherever was convenient, and even met for a year in St Andrews, where the building which housed it is still known as Parliament Hall. Indeed, that august edifice is home to the proceedings of the Union Debating Society, where the germinal gasbags of Scotland, and indeed of all three kingdoms, first enter the fray of political discourse.

In 1997, nearly three-hundred years after the Parliament was abolished, it was decided to bring it back, albeit in much reduced form. Great were the rumours and discussions about what effect the return of legislative power might have on the country, and Edinboronians pondered where the body might be housed. There were obvious choices, and less obvious choices, but in the end the Westminster government decided to go for the choice that hadn’t been suggested at all and built one of the most heinous offences against the sensibilities of taste that the land has ever seen. And so, the fact is that Scotland has three beautiful parliament buildings, none of which it uses. (more…)

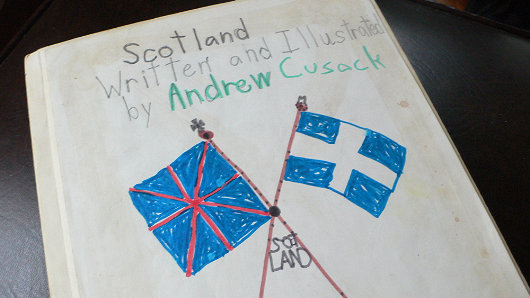

Scotland

Written and illustrated by Andrew Cusack (at 7 years of age)

Were I to review this book, I would say it is riddled with inaccuracies and depicts a stereotypical Hollywood version of Scotland far-removed from reality. But then, it was written in 1991 by a seven-year-old (yours truly), which is already eighteen years ago now. The ultimate schoolboy error is that I was apparently incapable at age 7 of producing a vexillologically accurate reproduction of the Saltire. My incorrect version of the Scottish appears like the old Greek flag, a white cross extended across a blue field. (See the correct flag here). (more…)

Stoddart’s Ode to Ossian

The Queen’s Sculptor Plans Great Literary Monument in the West of Scotland

Word reaches me that Alexander Stoddart, the Queen’s Sculptor in Ordinary for Scotland, has dreamed up a massive monument to Ossian. “For fifteen years Stoddart has planned ‘a national Ossianic monument’ on the west coast of Scotland,” writes Ian Jack in The Guardian. “The scale is immense. Stoddart wants a great amphitheatre cut into the rock with Ossian’s dead son, Oscar, also cut from rock, prone on his shield on the amphitheatre’s floor.” The project would be the biggest literary monument in the world, surpassing the Scott Monument on Princes Street in Edinburgh. It could be the project of a lifetime for Stoddart.

“He says a lot of people are keen, including Scottish government ministers, landowners and historians, and that a site has been identified in Morvern and a preliminary survey completed by the engineers Ove Arup. There is also environmental opposition: the kind of people, according to Stoddart, who will ‘always find two mating ptarmigan no matter where we choose’ and haven’t taken into account Schopenhauer’s view that ‘the sound of nature is the sound of perpetual screaming’. It may account for the two death threats he says he has received.”

“The Ossian poems, especially ‘Fingal’, took Europe by storm,” the journalist continues, “and gave it a new notion of the savage and sublime. A cave on Staffa became ‘Fingal’s Cave’. Goethe incorporated Ossian into The Sorrows of Young Werther and Schubert used passages of Goethe’s translation in his lieder. By Stoddart’s estimate, nothing, not even the work of Burns, has made a larger Scottish contribution to European culture. Ossian established the Scottish wilderness as a destination for Europe’s earliest tourists. Also, by ennobling Celtic antiquity, it changed Scotland’s sense of itself.”

The traditional style of Alexander Stoddart, an avowed neo-classicist, has provoked foaming at the mouth in the rather dull arts establishment, but his works — such as the David Hume statue on the Royal Mile and the frieze on the Sackler Library at Oxford — have proven popular. Scotland’s greatest living sculptor has completed a bust of Scotland’s greatest living composer, James Macmillan, as well as of Britain’s greatest living philosopher Roger Scruton. (The old-school lefty Tony Benn — another living national institution — is the subject of a Stoddard bust as well).

“The paradox is that, by revering and understanding abandoned traditions, [Stoddart] has emerged as one of the most original artists in Britain: a stranger to his times.”

The End of India Street

Photograph by Dave Henniker.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Waarburg October 2, 2024

- A Prize for the General September 23, 2024

- Articles of Note: 17 September 2024 September 17, 2024

- Equality September 16, 2024

- Rough Notes of Kinderhook September 13, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories