Rhodesia

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

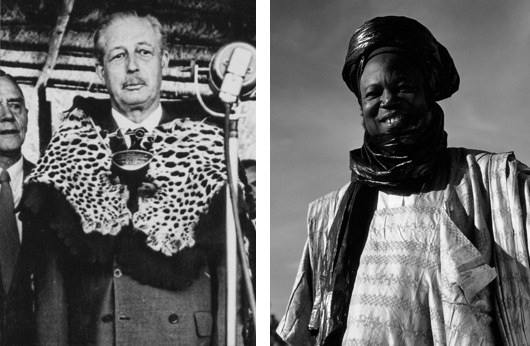

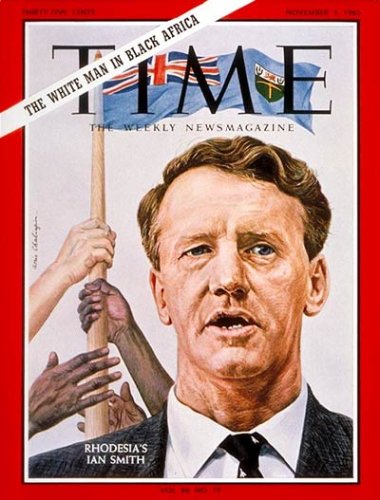

Supermac and the Sarduana

Macmillan’s Attitude to Class and Race in the Late Empire

Left: Harold Macmillan touring Africa in 1960; Right: Sir Ahmadu Bello, the Sarduana of Sokoto.

Staying over with some Kenyan friends in Wiltshire the other day, the old observation came up that, after the war, the officers settled in Kenya while the sergeants went to Rhodesia. While some of the leading lights of UDI had, in fact, been officers — Ian Smith an obvious case — it’s interesting to note that most of them came from humble backgrounds.

“Smithie” was born well-off in Rhodesia but his father had been a butcher’s son who went out to Africa and made good. Clifford Dupont, the first president of the Rhodesian republic, was born in London of poor East End Huguenot stock. His father had done well in the rag trade and got his son to Cambridge; Clifford became an artillery officer before emigrating to Africa.

Rhodesian Prime Minister Roy Welensky’s father was a Russian Jewish horse smuggler who married a ninth-generation Afrikaner. Roy was the couple’s thirteenth son, and left school at 14 to work on the railways and found success through the trade union movement.

Harold Macmillan, meanwhile, was a Guards officer and Old Etonian who had studied at Oxford. His famous ‘Wind of Change’ speech was just part of the British prime minister’s grand tour of Africa. “Supermac” started in Nigeria, where — unlike in some other parts of the continent — much of the native aristocracy had been preserved and coopted throughout colonial rule.

Proving Orwell’s observation that the English are the most class-ridden nation on earth, the PM felt comfortable amongst black African patricians in a way he couldn’t amongst members of the ruling white African elite from humble backgrounds.

In one of the ICBH’s oral history group discussions, Perry Worsthorne relates:

Somebody at some point has to mention, in any discussion of British politics, snobbery and class. I remember travelling and reporting on the ‘Wind of Change’ speech. We went to stay on the last bit, just before going on to Salisbury, was it the Sardauna of Sokoto who was he the premier of the Northern Nigerian region. Macmillan talked to us after he had seen him, he was flying on to Welensky the next day.

Macmillan used to have a sundowner with the correspondents covering his trip, and over whisky and sodas he told us how much more at home he felt with the Sardauna, who reminded him of the Duke of Argyll – ‘a kind of black highland chieftain’ – than he would feel in Salisbury as the guest of a former railwayman, Sir Roy Welensky. Snobbery, pure snobbery.

The British metropole was always ready to make racial distinctions and discriminate accordingly, yet it still tended to look upon outright racism with an air of disdain, as something slightly unsporting (or worse: foreign).

In the imperial periphery, racial attitudes amongst whites often differed greatly from Britain. This was most obviously so in South Africa, which for all intents and purposes embarked upon a radical revolutionary rejection of the British model of governance from 1948 with the implementation of apartheid. Rhodesia, needless to say, was another exception, if arguably more mild. “How different it would all have been,” Worsthorne somewhat patronisingly wondered, “if Ian Smith had been a gentleman.”

Meanwhile Nigeria’s Sir Ahmadu Bello — the Sarduana of Sokoto — was a statesman of cautious action, and his refusal to become Nigerian prime minister upon independence (he preferred sticking to his existing role as the powerful premier of the northern province) sadly deprived the federal state of the wisdom and experience which may have prevented its later descent into disarray. He was murdered by Major Nzeogwu during the 1966 coup d’état.

Differences of race or class aside, it’s telling that both the white low-born railwayman Welensky and the black patrician Bello ended up as knights of the realm.

“Events did not choose the terrorists; powerful white people did.”

Helen Andrews on Zimbabwe

Robert Mugabe leading Ian Smith into the Zimbabwean parliament, 1980.

It is rare to find journalism as informed and insightful as this piece on Zimbabwe by Helen Andrews in National Review. In the aftermath of Mugabe’s clumsy downfall and his succession by a powerful apparatchik and experienced political operator, Helen explores the Rhodesian crisis and attempts to answer the question: could it really have gone any other way?

Any idea that liberal reform on the part of the Rhodesian state could have saved it is a non-starter, because the anti-imperialists were implacable and — I do not know a gentle way to put this — they were quite happy to lie. I do not mean just the professional liars of the Soviet propaganda shop, or the pundits who lazily referred to the Rhodesian system as “apartheid,” or the guerrillas who told Shona villagers that ZANU had successfully dynamited the Kariba Dam, or the foreign journalist who scattered candy around a garbage bin and captioned the resulting photo “Starving children searching for food in Salisbury.” Ralph Bunche had a doctorate from Harvard, a Nobel Peace Prize, and a co-author credit on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and when it came to imperialism, he lied.

“Colonial authorities like the noted Englishman, Lord Lugard, doubt that the African race, whether in Africa or America, can develop capability for self-government.” When I first read that in Bunche’s 1936 pamphlet “A World View of Race,” I felt a lurking suspicion that I had read a sentence of Lord Lugard’s beginning with the very words “The method of their progress toward self-government lies…” I had. His next words are “along the same path as that of Europeans.” Even making allowances for CTRL-F’s not having been invented yet, Bunche’s remark is plain slander. With Harvard Ph.D.s pulling stunts like this, it is hard to summon much indignation at a garden-variety diplomatic lie like the U.N. claim, by which sanctions were justified, that Rhodesia had committed an act of aggression by maintaining its status quo.

She does go a little easy on Smith, who despite his many strengths was just as willing to play fast and easy with the truth. (He was a politician, after all.) But then as we are so used to hearing that Smithie was a little Hitler it’s a welcome restorative.

When I moved to South Africa, I did so at least in part because I wanted to see it before it became “the next Zimbabwe”. Having come back, I was impressed by the relative robustness of many of its institutions, and the certain robustness of many of its people. Rather than a Zimbabwe-style collapse, South Africa seemed destined for a slow, ungainly descent into perpetual malaise.

The recent ascent of Cyril Ramaphosa – who on behalf of the ANC ran rings round the NP negotiators during the transition talks of the early ’90s – gives hope to many. I’m too cautious to be optimistic, but Mr Ramaphosa is clever, intelligent, skilful, and more likelier to keep the unions on side.

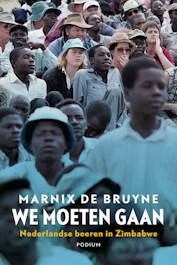

The Dutch in Rhodesia

…and why they stayed there.

Journalist Marnix de Bruyne has shed new light on the post-war wave of Dutch immigration to Rhodesia with his new book, We moeten gaan. Nederlandse boeren in Zimbabwe (‘We Must Go: Dutch Farmers in Zimbabwe’).

Journalist Marnix de Bruyne has shed new light on the post-war wave of Dutch immigration to Rhodesia with his new book, We moeten gaan. Nederlandse boeren in Zimbabwe (‘We Must Go: Dutch Farmers in Zimbabwe’).

Why did so many people emigrate from the Netherlands in the fifties? Why did hundreds of them choose to settle in what was then called Rhodesia, today’s Zimbabwe? And why did so many of them stay after 1965, when the country was led by a white-minority regime, faced an international boycott and was engulfed in a bloody guerrilla war?

De Bruyne attempted to answer these questions through a recent seminar at Leiden University’s African Studies Centre. The university has rather handily made a recording of the seminar available online.

Daar’s ook ’n interview (in Nederlands) met Mnr de Bruyne in Mare, die koerant van die Universiteit Leiden.

(Dave: hierdie post is vir jy!)

Olympic Teams of Yesteryear

The vanished lands and failed alliances of the Modern Olympiad

THE GAMES OF THE Modern Olympiad are events which are meant to bring the peoples of the world together in peace and harmony and all those good and heartening things, but from the very beginning they have gotten bogged down in the petty particularities of rival nations, which altogether makes them rather more fun and interesting, if perhaps a touch less high-minded. The story of the ancient gathering’s revival in 1896 through the efforts of Pierre Frédy, Baron de Coubertin is well-known. Athletes from at least fourteen countries participated in those first modern games in Athens over a century ago, though the concept of national teams was not introduced until the 1906 games (the Intercalated Games, which have since been de-recognised by the IOC). But since those first games towards the end of the nineteenth century, the fortunes of many lands have waxed and waned, and likewise the spirit of unity amongst various peoples vied with the spirit of distinctiveness. Here, then, are but a small sample of Olympic teams which once vied for gold but which can no longer be found among the Olympic competitors of today. (more…)

The Prime Minister & His Wife

The Rt Hon Ian Douglas Smith & Mrs Smith, at home in Salisbury, Rhodesia.

Theodore Dalrymple on Rhodesia

The young black doctors who earned the same salary as we whites could not achieve the same standard of living for a very simple reason: they had an immense number of social obligations to fulfill. They were expected to provide for an ever expanding circle of family members (some of whom may have invested in their education) and people from their village, tribe and province. An income that allowed a white to live like a lord because of a lack of such obligations scarcely raised a black above the level of his family. […]

It is easy to see why a civil service, controlled and manned in its upper reaches by whites could remain efficient and uncorrupt but could not long do so when manned by Africans who were suppose to follow the same rules and procedures. The same is true, of course, of every other administrative activity, public or private. The thick network of social obligations explains why, while it would have been out of the question to bribe most Rhodesian bureaucrats, yet in only a few years it would have been out of the question not to try to bribe most Zimbabwean ones, whose relatives would have condemned them for failing to obtain on their behalf all the advantages their official opportunities might provide. Thus do they very same tasks in the very same offices carried out by people of different cultural and social backgrounds result in very different outcomes.

Viewed in this light, African nationalism was a struggle for power and privilege as it was for freedom, though it co-opted the language of freedom for obvious political advantage.

The Mandarins and the Masses

“We Live in Hope”

Ian Smith, the Grand Old Man of Africa, Speaks

Here is an interesting nine-minute-long clip from a documentary on Ian Smith, the former Prime Minister of Rhodesia, featuring the Hon. Mr. Smith himself, now eighty-eight years of age, as well as Kathy Olds, a landowner, and Ernest Mtunzi, a former aide to ZAPU leader Joshua Nkomo.

“What we believed in was responsible majority rule, as opposed to irresponsible majority rule and I stand by that,” Mr. Smith tells the interviewer. “I think it is important that before you give a person the vote you ensure that his roots go down, that he’s part of the whole structure of the country.”

“Smith is an African,” Ernest Mtunzi says. “He understands the African mentality. […] Smith was being realistic. If you give people something before they’re ready, they’re going to mess it up. And that has happened.”

“Africa is a continent which is subject to a great deal of friction and argument and change,” Smith concludes. “That’s part of the world generally but more so Africa than anywhere else. So because of that we live in hope. We think that the people they in the end will say we’ve had enough.”

“In the interest of our people and of other people this part of the world, let’s work together. […] Let’s just accept that we are all part of Africa, all part of the world. Let’s all work together and the more we can get people to accept that philosophy I think the greater the hope for the whole world.”

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

- American Exuberant February 10, 2025

- Crux Alba Journal Launch February 10, 2025

- The Year in Film: 2024 February 10, 2025

- Articles of Note: 27 January 2025 January 27, 2025

Most Recent Comments

- on When an American aristocrat meets a European Grand Duke

- on The Year in Film: 2024

- on Jesuit Gothic

- on The Borough Synagogue

- on No. 82, Eaton Square

- on Christ Church

- on The Last Will and Testament of Louis XVI

- on Amsterdam

- on Season’s Greetings from the Seventh

- on Season’s Greetings from the Seventh

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories