Politics

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Vote AR

The lush and verdant tree formed in the shape of the Netherlands grows from deep roots spelling out ‘AR’, the name of the main Protestant party — once led by Abraham Kuyper.

As Kamps and Voerman point out in their book on posters from the Dutch Christian-democratic tradition (in print / online), this poster is a “rather complicated allegorical representation”.

Equality

I find that they’re not true without looking further than myself. I don’t deserve a share in governing a hen-roost, much less a nation. Nor do most people — all the people who believe advertisements, and think in catchwords, and spread rumours. The real reason for democracy is just the reverse. Mankind is so fallen that no man can be trusted with unchecked power over his fellows. Aristotle said that some people were only fit to be slaves. I do not contradict him. But I reject slavery because I see no men fit to be masters.

This introduces a view of equality rather different from that in which we have been trained. I do not think that equality is one of those things (like wisdom or happiness) which are good simply in themselves and for their own sakes. I think it is in the same class as medicine, which is good because we are ill, or clothes which are good because we are no longer innocent. I don’t think the old authority in kings, priests, husbands, or fathers, and the old obedience in subjects, laymen, wives, and sons, was in itself a degrading or evil thing at all. I think it was intrinsically as good and beautiful as the nakedness of Adam and Eve. It was rightly taken away because men became bad and abused it. To attempt to restore it now would be the same error as that of the Nudists. Legal and economic equality are absolutely necessary remedies for the Fall, and protection against cruelty.

But medicine is not good. There is no spiritual sustenance in flat equality. It is a dim recognition of this fact which makes much of our political propaganda sound so thin. We are trying to be enraptured by something which is merely the negative condition of the good life. And that is why the imagination of people is so easily captured by appeals to the craving for inequality, whether in a romantic form of films about loyal courtiers or in the brutal form of Nazi ideology. The tempter always works on some real weakness in our own system of values: offers food to some need which we have starved.

When equality is treated not as a medicine or a safety-gadget but as an ideal we begin to breed that stunted and envious sort of mind which hates all superiority. That mind is the special disease of democracy, as cruelty and servility are the special diseases of privileged societies. It will kill us all if it grows unchecked. The man who cannot conceive a joyful and loyal obedience on the one hand, nor an unembarrassed and noble acceptance of that obedience on the other, the man who has never even wanted to kneel or to bow, is a prosaic barbarian. But it would be wicked folly to restore these old inequalities on the legal or external plane. Their proper place is elsewhere.

We must wear clothes since the Fall. Yes, but inside, under what Milton called “these troublesome disguises,” we want the naked body, that is, the real body, to be alive. We want it, on proper occasions, to appear: in the marriage-chamber, in the public privacy of a men’s bathing-place, and (of course) when any medical or other emergency demands. In the same way, under the necessary outer covering of legal equality, the whole hierarchical dance and harmony of our deep and joyously accepted spiritual inequalities should be alive. It is there, of course, in our life as Christians: there, as laymen, we can obey — all the more because the priest has no authority over us on the political level. It is there in our relation to parents and teachers — all the more because it is now a willed and wholly spiritual reverence. It should be there also in marriage.

This last point needs a little plain speaking. Men have so horribly abused their power over women in the past that to wives, of all people, equality is in danger of appearing as an ideal. But Mrs. Naomi Mitchison has laid her finger on the real point. Have as much equality as’ you please — the more the better — in our marriage laws: but at some level consent to inequality, nay, delight in inequality, is an erotic necessity. Mrs. Mitchison speaks of women so fostered on a defiant idea of equality that the mere sensation of the male embrace rouses an undercurrent of resentment. Marriages are thus shipwrecked. This is the tragi-comedy of the modern woman; taught by Freud to consider the act of love the most important thing in life, and then inhibited by feminism from that internal surrender which alone can make it a complete emotional success. Merely for the sake of her own erotic pleasure, to go no further, some degree of obedience and humility seems to be (normally) necessary on the woman’s part.

The error here has been to assimilate all forms of affection to that special form we call friendship. It indeed does imply equality. But it is quite different from the various loves within the same household. Friends are not primarily absorbed in each other. It is when we are doing things together that friendship springs up— painting, sailing ships, praying, philosophising, fighting shoulder to shoulder. Friends work in the same direction. Lovers look at each other: that is, in opposite directions. To transfer bodily all that belongs to one relationship into the other is blundering.

We Britons should rejoice that we have contrived to reach much legal democracy (we still need more of the economic) without losing our ceremonial Monarchy. For there, right in the midst of our lives, is that which satisfies the craving for inequality, and acts as a permanent reminder that medicine is not food. Hence a man’s reaction to Monarchy is a kind of test. Monarchy can easily be “debunked”; but watch the faces, mark well the accents, of the debunkers. These are the men whose tap-root in Eden has been cut: whom no rumour of the polyphony, the dance, can reach — men to whom pebbles laid in a row are more beautiful than an arch. Yet even if they desire mere equality they cannot reach it. Where men are forbidden to honour a king they honour millionaires, athletes, or film-stars instead: even famous prostitutes or gangsters. For spiritual nature, like bodily nature, will be served; deny it food and it will gobble poison.

And that is why this whole question is of practical importance. Every intrusion of the spirit that says “I’m as good as you” into our personal and spiritual life is to be resisted just as jealously as every intrusion of bureaucracy or privilege into our politics. Hierarchy within can alone preserve egalitarianism without. Romantic attacks on democracy will come again. We shall never be safe unless we already understand in our hearts all that the anti-democrats can say, and have provided for it better than they. Human nature will not permanently endure flat equality if it is extended from its proper political field into the more real, more concrete fields within. Let us wear equality; but let us undress every night.

Articles of Note: 13 March 2024

My then-flatmate was getting married the next day and much pottering-about sorting things was required but the idiosyncratic beauty of this building captured my imagination — part Norman, part Moorish. I was almost insulted that I hadn’t come across it in any of my bookish explorations.

The historian Edmund Harris covers Chideock in his lusciously illustrated post on Recusancy in Dorset and the ‘other tradition’ of Catholic church-building.

■ Generations ago it was said that the three institutions no British politician dared offend were the trade unions, the Catholic Church, and the Brigade of Guards. In 2020s Britain there is only one caste which must always be obeyed: the ageing, moneyed homeowners.

Not only do these “NIMBYs” (“Not In My Back Yard”) jealously guard their freeholds, they do whatever they can to prevent more houses being built to guard the value of their prize possessions, vastly inflated by a combination of lacklustre housebuilding and irresponsible leap in migration. As old people vote and young people don’t — and when they do, vote badly — few sensible people can find a way out of this quagmire.

It might be worth looking to the Mediterranean, where Tal Alster tells us How Israel turned urban homeowners into YIMBYs.

■ It’s disappointingly rare to see intelligent outsiders give a considered impression of the current state of play in the Netherlands — that’s Mother Holland for us New Yorkers. Too often commentators in English are either rash cheerleaders for the hard right or bien-pensant liberals eager to castigate and chastise. Both rush to judgement.

What a rare diversion then to read Christopher Caldwell — the only thinking neo-con? — attempt to explore and explain the success of Geert Wilders in the recent Dutch elections.

■ One in ten of Lusitania’s inhabitants are now immigrants, and this discounts those — many from Brazil and other former parts of the once-world-spanning Portuguese empire — who have managed to acquire citizenship through various routes.

Ukrainian number-plates are now frequently be seen on the roads of Lisbon, as far in Europe as you can get from Big Bad Uncle Vlad.

Vasco Queirós asks: Who is Portugal for?

■ Speaking of world-spanning empires, in true andrewcusackdotcom fashion, we haven’t had enough of the Dutch — but we have had enough of their wicked wayward heresies.

Historian Charles H. Parker explores the legacies of Calvinism in the Dutch empire.

■ The City of New York itself is the best journalism school there is. Jimmy Breslin dropped out of LIU after two years, eventually taking up his pen. Pete Hamill left school at fifteen, apprenticed as a sheet metal worker, and joined the navy.

William Deresiewicz argues that a dose of working-class realism can save journalism from groupthink.

■ The New Yorker tells us how a Manchester barkeep found and saved a lost (ostensible) masterpiece of interwar British literature.

■ Our inestimable friend Dr Harshan Kumarasingham explores David Torrance’s history of the first Labour government on its hundredth anniversary.

■ And finally, one for nous les normandes (ok, ok, celto-normandes): Canada’s National Treasure David Warren briefly muses that the Norman infusion greatly refined Anglo-Saxon to give us the superior English tongue we speak today.

De Gaulle on the Market

It forces people to stretch themselves, it gives a bonus to the best, it encourages you to surpass others and to surpass yourself.

But, at the same time, it creates injustices, it establishes monopolies, it favours cheaters.

So don’t be blind to the market. You should not imagine that it will solve every problem on its own.

The market is not above the nation and the state. It is the nation, it is the state which must oversee the market. »

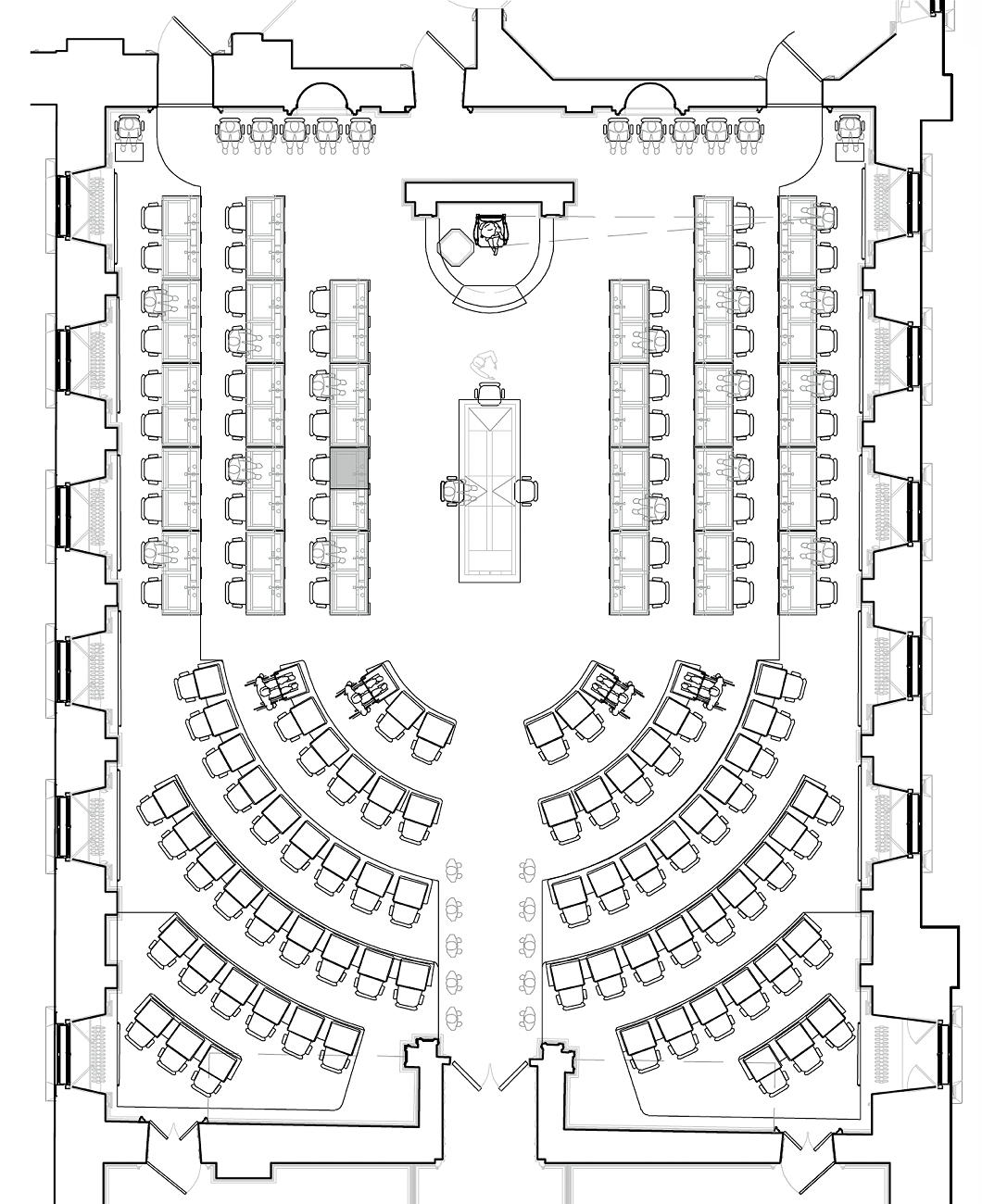

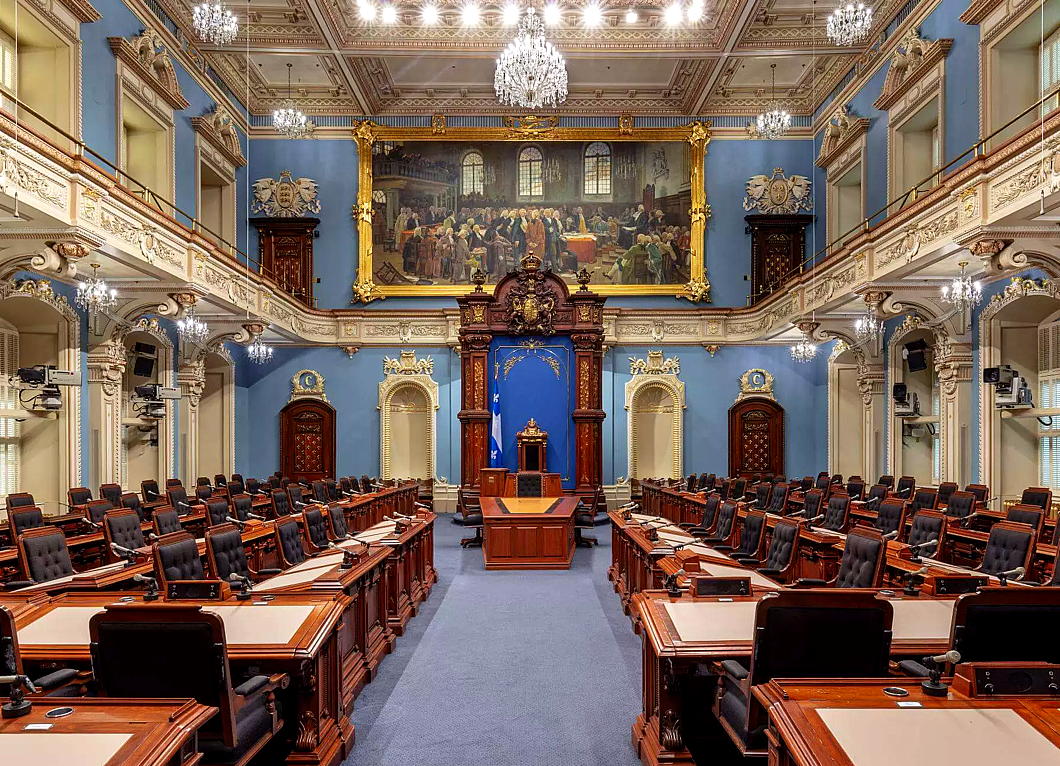

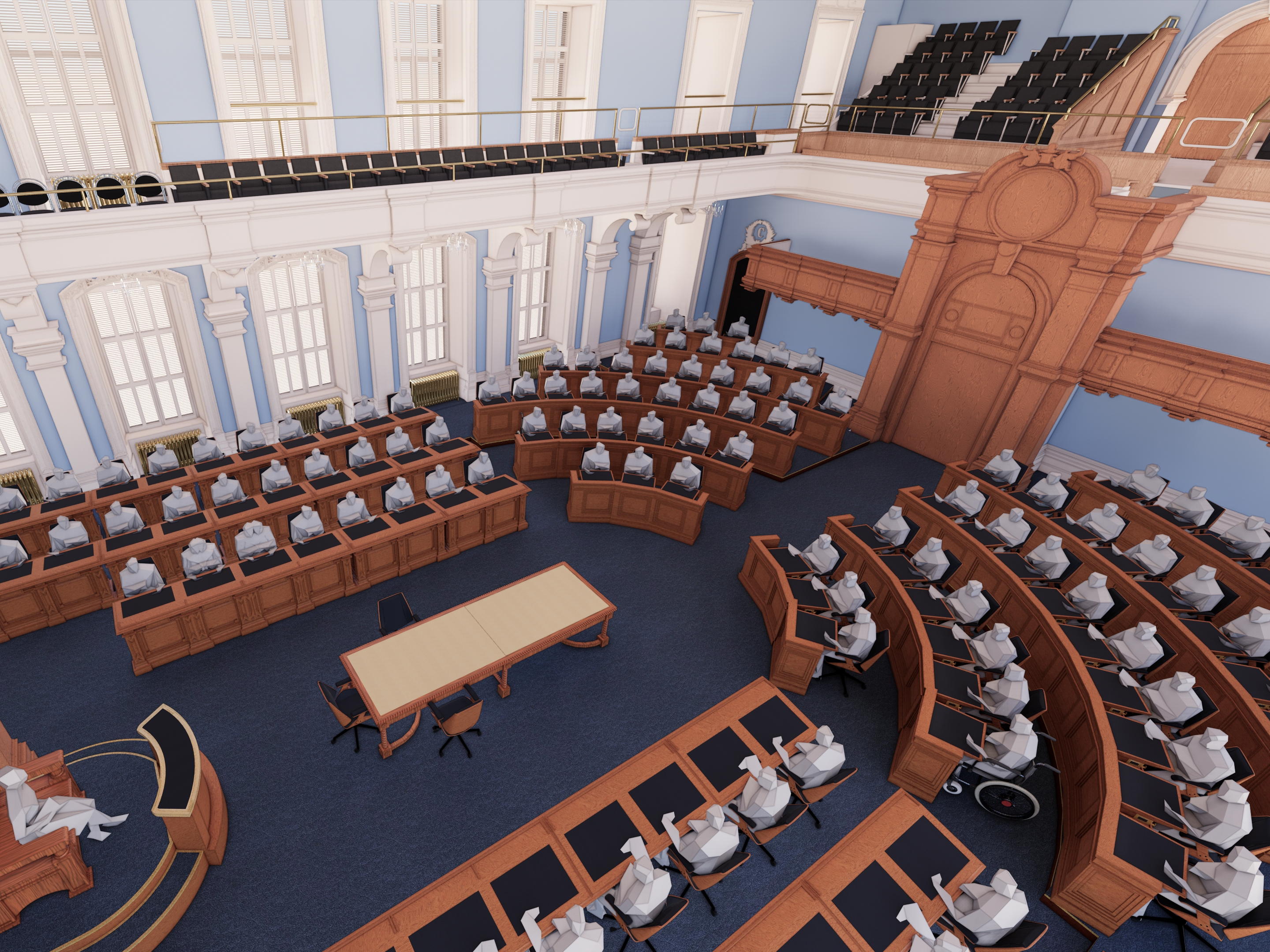

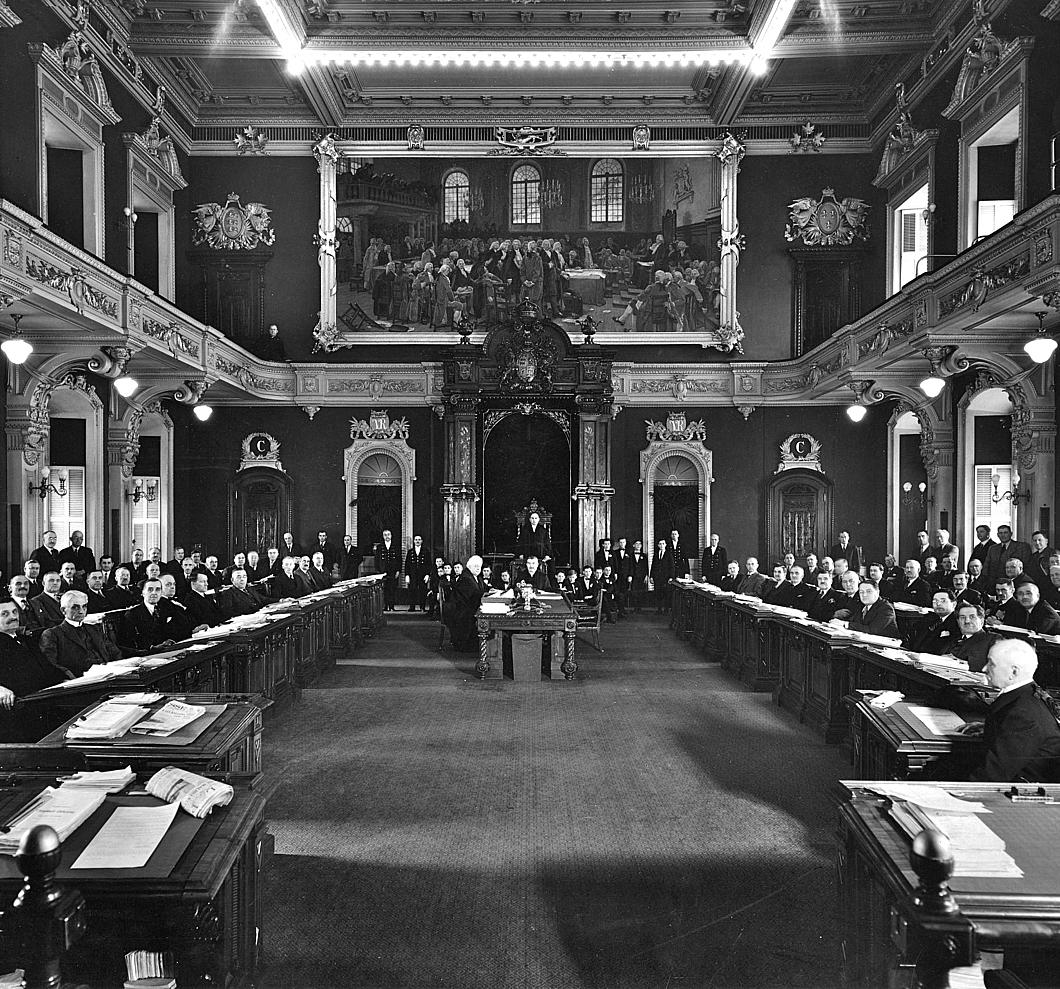

Horseshoe for Quebec’s Salon bleu

Refit will change seating plan in Quebec’s parliament chamber

An upcoming renovation to the Hôtel du parlement in Quebec City will also bring a change in the seating plan of the Assembly’s parliamentary chamber. Deputés agreed a moderate alteration to the current Westminster-style seating plan: a horseshoe shape will replace the crowded back two rows of desks with a curved arrangement.

The original clerks’ table designed by the building’s architect, Eugène-Étienne Taché, in 1886 will also be returned to centre-stage in the Salon bleu (formerly the Salon vert) of Quebec’s National Assembly. The room is also, I believe, the only parliamentary chamber to feature in a film by Alfred Hitchcock.

Renovations are scheduled to begin in January of next year, when deputés will start convening in the Salon rouge that formerly housed Quebec’s Legislative Council, abolished in 1968. (Quebec was the last Canadian province to abolish the upper house of its parliament.)

“The Salon bleu has a strong symbolic value for the Quebec nation,” claims Éric Montigny, professor of political science at Laval University (founded 1663).

“We must respect this tradition and evolve in a very, very gradual manner,” Professor Montigny told the Journal de Québec. “A parliament is not trivial.”

The Assembly numbered only sixty-five members when Taché’s edifice was completed in 1886, while today 125 deputés have to fit into the parliamentary chamber.

The new arrangement would make room for as many as 130 legislators, plus the Président in the speaker’s chair. It will also allow for a good number of the historic desks in the chamber to be retained.

Other potential arrangements were considered and rejected, including introducing a half-moon hemicycle akin to Paris, Washington, and other republican legislatures.

Prof Montigny dismissed claims that semicircular arrangements lead to more collaborative dialogue and constructive work between government and opposition parties:

“It’s an argument that is raised regularly, but I don’t know of any studies that will support this theory.”

The most significant change to the chamber in recent years was the removal of the crucifix from above the président’s chair, first installed in 1936 by the giant of Quebec politics, premier Maurice Duplessis.

That crucifix, and its 1982 replacement, were removed in 2019 and are now displayed as historical artefacts in an ancillary part of the parliament building.

[NDLR: I wrote about the crucifix back in 2008.]

The horseshoe seating plan seems a happy compromise: Westminster-style parliaments — even those that are unicameral like Quebec’s — are honest about the antagonism between government and opposition, and the horseshoe preserves the antiphonal arrangement conducive to this, while rounding it off with a curve at the end.

For my part, I will be happy to see the removal of the arbitrary trapezoid of the modern clerks’ table (below) and its replacement by its historic predecessor.

30 mai 1968

The events of May 1968 have been fetishised by the romantic radical left but ended in the triumph of the popular democratic right. Battered by two world wars, France had enjoyed an unprecedented rise in living standards since 1945 — especially among the poorest and most hard-working — and a new generation untouched by the horrors of war and occupation had risen to adulthood (in age if not in maturity). The ranks of the middle class swelled as more and more people enjoyed the material benefits of an increasingly consumerised society, while those left behind shared the same aspirations of moving on up.

Like any decadent bourgeois cause, the spark of the May events was neither high principle nor addressing deep injustice but rather more base impulses: male university students at Nanterre were upset they were restricted from visiting female dormitories (and that female students were restricted from visiting theirs). The ensuing events involved utopian manifestos, barricades in the streets, workers taking over their factories, a day-long general strike and several longer walkouts across the country.

The French love nothing more than a good scrap, especially when it’s their fellow Frenchmen they’re fighting against. Working-class police beat up middle-class radicals but for much of the month both sides made sure to finish in time for participants on either side to make it home before the Métro shut for the evening. But workers’ strikes meant everyday life was being disrupted, not just the studies of university students. When concessions from Prime Minister Georges Pompidou failed to calm the situation there were fears that the far-left might attempt a violent overthrow of the state.

De Gaulle himself, having left most affairs in Pompidou’s hands, finally came down from his parnassian heights to take charge but then suddenly disappeared: the government was unaware of the head of state’s location for several tense hours.

It turned out the General had flown to the French army in Germany, ostensibly to seek reassurance that it would back the Fifth Republic if called upon to defend the constitution. De Gaulle is said to have greeted General Massu, commander of the French forces in West Germany, “So, Massu — still an asshole?” “Oui, mon général,” Massu replied. “Still an asshole, still a Gaullist.”

The morning of 30 May 1968, the unions led hundreds of thousands of workers through the streets of Paris chanting “Adieu, de Gaulle!” The police kept calm, but the capital was tense and there was a sense that things were getting out of hand. Pompidou convinced de Gaulle the Republic needed to assert itself.

Threatened by a radicalised minority, de Gaulle called upon the confidence of the ordinary people of France. At 4:30 he spoke on the radio briefly, announcing that he was calling for fresh elections to parliament and asserting he was staying put and that “the Republic will not abdicate”.

Before the General even spoke some his supporters (organised by the ever-capable Jacques Foccart) were already on the avenues but the short four-minute broadcast inspired teeming masses onto the streets of central Paris, marching down the Champs-Élysées in support of de Gaulle.

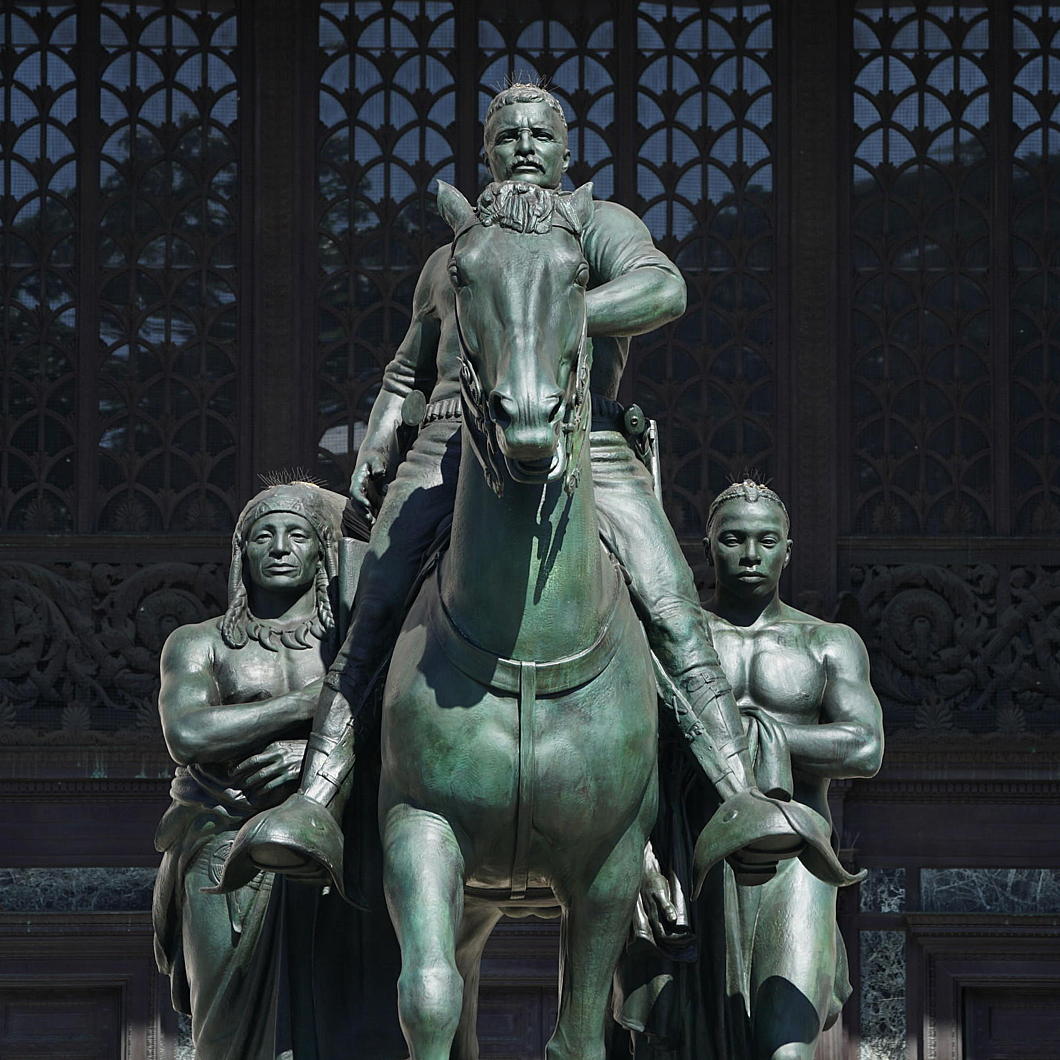

Theodore Roosevelt

The ancient heresy of iconoclasm claimed a new victim this week: The statue of Theodore Roosevelt which graced the Manhattan memorial dedicated to him at the American Museum of Natural History has been removed at a cost of two million dollars.

The sculpture had attracted the ire of protestors who objected to the inclusion of a Native American and an African by the side of twenty-sixth President of the United States and sometime Governor of New York, which they claimed glorified colonialism and racism.

While the American Museum of Natural History is a private institution, it sits on land owned by the City, and the statue was paid for by the State.

The statue was doomed in June of last year when the New York City Public Design Commission voted unanimously to rip Teddy down.

As the New York Post put it, “He’s going on a rough ride!”

The statue was severed in two this week, with the top half removed and the bottom half following shortly after.

It will be shipped to the Badlands of North Dakota to be displayed as an object in a museum under construction there. (more…)

Problems and Solutions

There are in some periods problems to which no solutions exist.”

Fifth Republic Britain

An Anglo-Gaullist Reading Round-up

While I’m a big Adenauer fan there’s little doubt that de Gaulle was the greatest European statesman of the twentieth century and an historical figure of such a position will always be the subject of interest.

Both Jonathan Fenby’s 2010 book The General: Charles de Gaulle and the France He Saved and Dr Sudhir Hazareesingh’s 2012 In the Shadow of the General: Modern France and the Myth of de Gaulle received wide notice, but neither as much as Julian Jackson’s 2019 A Certain Idea of France: The Life of Charles de Gaulle.

Jackson’s work is indeed magisterial and Lord Sumption’s praise of it as “the best biography of de Gaulle in any language” is only just an exaggeration. (For a strong bibliography of works on the general, see the appendix of Charles Williams’s 1993 The Last Great Frenchman: A Life of General de Gaulle.)

Study of the life and contradictions of de Gaulle is always worthwhile, but many spy a Gaullist moment in the Tory party’s refreshingly surprising turn away from ideological liberalism towards a more pragmatic conservatism under Boris Johnson.

Painting Johnson as Britain’s first Gaullist prime minister would be a stretch, but there is certainly some crossover: nationalist, economically interventionist, focused on national sovereignty and national exceptionalism.

■ Eliot Wilson pointed out this summer that Boris has always been difficult to classify in ideological terms.

■ Speccie political editor James Forsyth wrote in The Times that Boris the Gaullist puts action over ideas. Just before the party conference Forsyth also predicted the PM’s speech would be “in line with his recent Gaullist turn”.

■ QMUL’s Nick Barlow explores the parallels between de Gaulle’s Fifth Republic and Boris’s style of government.

■ Meanwhile Aris Roussinos argues that de Gaulle was always right in vetoing British entry into the EEC, and that true-blue FBPE types should welcome Brexit as advancing the cause of European integration.

■ Dean Godson (New Statesman) says that Defence Secretary Ben Wallace is pursuing “almost Gaullist trajectory for future British policy”.

■ When asked (on GB News) where he sits on the political spectrum, national treasure Peter Hitchens expressed his surprise that the Gaullist combination of “strong defence, patriotism, a strong welfare state, and national independence” isn’t more common in British politics.

■ ‘Bagehot’, the political column in The Economist, put it that the man who rebuilt post-war France has some important lessons for Britain’s prime minister: What Boris could learn from de Gaulle.

■ The American Conservative embarrassingly illustrated a piece on Europe’s Gaullist Revival with a picture of General Kœnig. (Always check the képi — as a brigadier general, de Gaulle only had two stars!)

■ Mike Bird discerned some Anglo-Gaullism in a pile of recent newspaper headlines.

■ As long ago as 2017 — what a world away that was! — Prospect argued in a somewhat rambling piece that the Brexiteers were Britain’s new Gaullists.

■ Honourable mention: Frederick Studemann chides Churchill and dumps de Gaulle, saying Boris should model himself on Bismarck and make for a Prussian Brexit.

But, for all this, when New Labour bigwig John McTernan suggested that Boris is not a Churchill but a de Gaulle, the great Julian Jackson himself pointed out there are still great differences between the PM and le général.

All the same, I’m welcoming our Anglo-Gaullist future with open arms.

Articles of Note: 24.II.2021

• It is almost certain that we will never know who the actual winner of the 2020 presidential election was: the methods of fraud which might have been deployed are by their very nature ephemeral. Anton is right in that the best summary of the irregularities is from the U.S.-based Swedish academic Claes Ryn: How the 2020 Election Could Have Been Stolen. Ryn’s academic work is always an insightful read so his take here is worthwhile.

• I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: the Frenchman Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is always worth reading and always brings something to the table. P.E.G. argues the pre-Trumpers, anti-Trumpers, and never-Trumpers on the American centre-right need to recognise the reasons why Trump became a political phenomenon in the first place: Why Establishment Conservatives Still Miss the Point of Trump.

• One of the best books on urbanism in the Cusackian library is Allan Jacobs’s Great Streets. The expert work with its illustrative maps, diagrams, and line drawings is now a quarter-century old and on this anniversary Theo Mackey Pollack examines What Makes a Great Street.

• A new book argues that our vision of Northern Ireland as a corrupt and gerrymandered statelet from its birth in 1921 until the imposition of direct rule in 1972 is largely a myth. The editors Patrick J Roche and Brian Barton take to the pages of the once-great Irish Times to offer A Unionist History of Northern Ireland. It’s… an interesting perspective that will doubtless provoke a debate, but colour me sceptical.

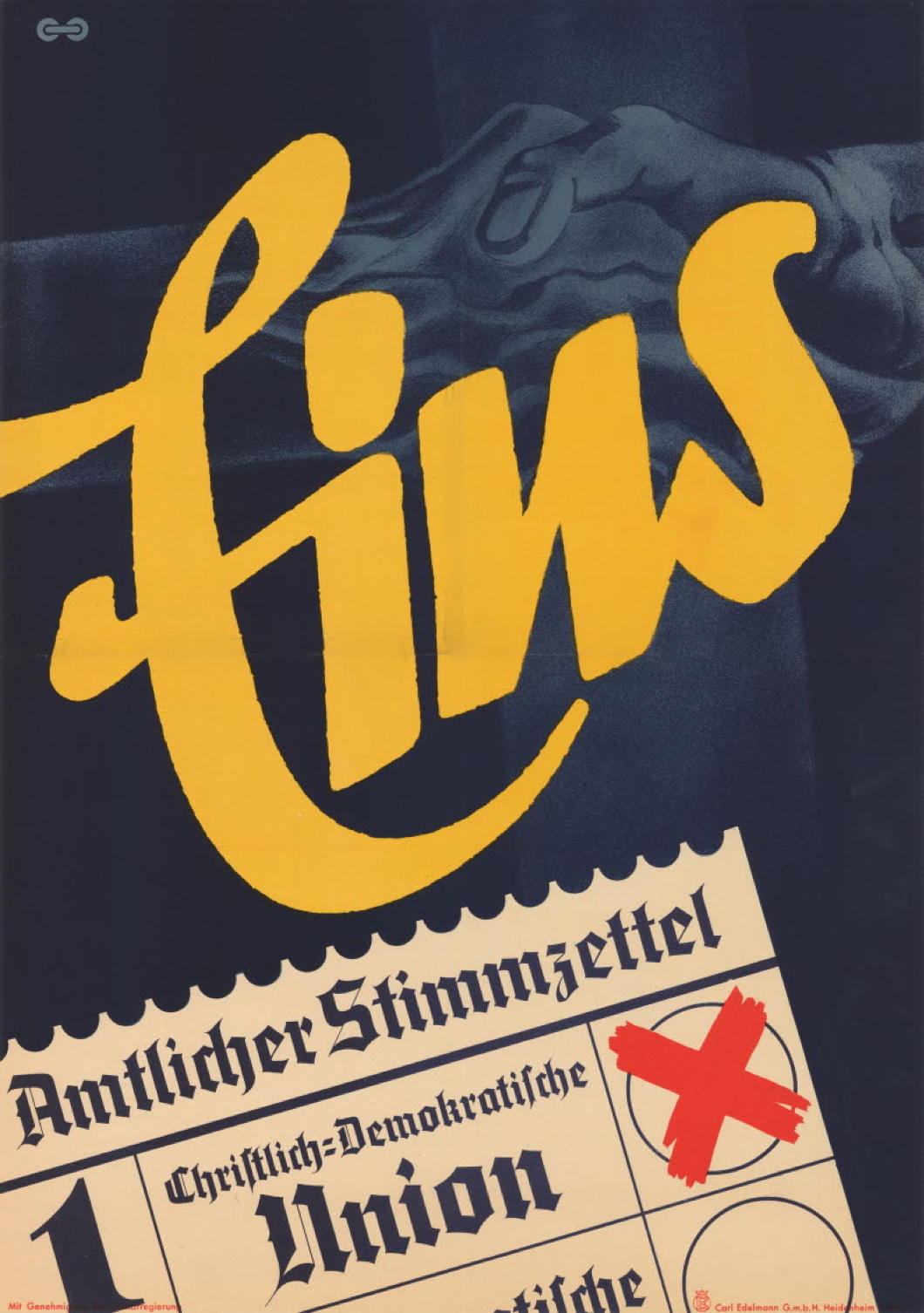

CDU @ 75

Last week was the seventy-fifth anniversary of the foundation of Germany’s Christian Democratic Union, one of the most successful democratic political parties in postwar Europe.

Indeed, under Adenauer the CDU was one of the institutions which transformed relations between the peoples of Europe and started the process of integration which, alas, has not aged well.

Nonetheless, here are some election posters from the early years of the CDU — plus one from the 1980s. (more…)

Observations

All those interested in the history of the workers’ struggle would have enjoyed a letter to the editor printed in last week’s Observer.

Floreat Etona, left and right

Alex Renton is correct when he points out that the 20 old Etonian MPs currently sitting are all Tories, but this is far from usually the case (“Our educational apartheid laid bare”, Books, New Review). The first OE to be elected a Labour MP was in 1923, and the party consistently had OE representation on its benches from then all the way to 2010. Even Clement Attlee’s transformative postwar Labour government included two old Etonians: Hugh Dalton as chancellor of the exchequer and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence as India secretary.

Andrew Cusack (Conservative, non-OE)

London SE1

Of course, no one actually reads the Observer, so it went entirely unnoticed.

I have acquired a dangerously successful rate of my pedantic missives being printed in periodicals. The editors of the Irish Times, Times Literary Supplement, Catholic Herald, and even the Tablet have all been guilty of lapses in judgement in this regard.

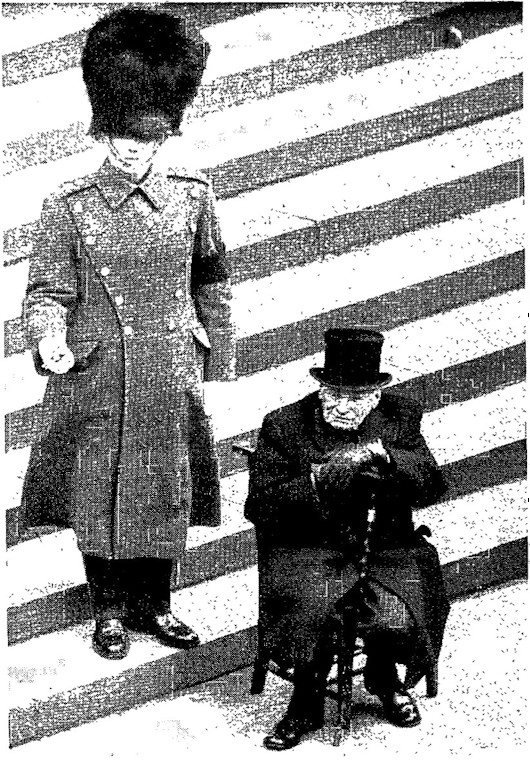

The Steps of the Throne

Who may sit on the steps of the throne in the House of Lords?

Much was made of the Prime Minister’s decision to sit in the House of Lords when they were going through stages of the bill to invoke Article 50 last year. Theresa May had the right to sit on the steps of the throne in the Lords chamber by virtue of being sworn to the Privy Council, as all holders of the four Great Offices of State are (and usually their opposition Shadows as well).

But who else is granted the privilege of lodging their posterior in such a prominent locale?

The Companion to the Standing Orders and Guide to the Proceedings of the House of Lords provides some guidance:

1.59 The following may sit on the steps of the Throne:

· members of the House of Lords in receipt of a writ of summons, including those who have not taken their seat or the oath and those who have leave of absence;

· members of the House of Lords who are disqualified from sitting or voting in the House as Members of the European Parliament or as holders of disqualifying judicial office;

· hereditary peers who were formerly members of the House and who were excluded from the House by the House of Lords Act 1999;

· the eldest child (which includes an adopted child) of a member of the House (or the eldest son where the right was exercised before 27 March 2000);

· peers of Ireland;

· diocesan bishops of the Church of England who do not yet have seats in the House of Lords;

· retired bishops who have had seats in the House of Lords;

· Privy Counsellors;

· Clerk of the Crown in Chancery;

· Black Rod and his Deputy;

· the Dean of Westminster.

The Earl Attlee

At Chartwell one weekend in Churchill’s presence, Sir John Rodgers made the mistake of referring to Clement Attlee, wartime deputy prime minister and postwar prime minister, as “silly old Attlee”. Churchill was having none of it.

“Mr Attlee is a great patriot,” he said. “Don’t you dare call him ‘silly old Attlee’ at Chartwell or you won’t be invited again.”

The leader of the Conservative party and the leader of the Labour party were obvious political rivals but developed a great bond by their shared experience in the cross-party War Cabinet.

En route to a dinner party the other night I happened to run into Attlee’s greatgrandson (an old friend) on the upper deck of the 414 bus. It reminded me of this photo (above) printed in the Observer. When the great bulldog went on to his eternal reward in 1965, the incredibly frail Earl Attlee insisted on attending the state funeral in St Paul’s Cathedral. Though younger, he only managed to outlive him by two years.

Attlee had been raised to the House of Lords (where he spoke against Britain joining the EEC) in 1956 and, rather appropriately, he chose as the motto for his coat of arms Labor vincit omnia — Labour conquers all.

Fillon: Which Right?

A Rémondian Analysis of the French Presidential Candidate

One of the most significant contributions of the historian and political scientist René Rémond was his theory regarding the tendencies of the French right wing. He contended that, broadly speaking, there are three right wings in France: legitimist, bonapartist, and orleanist. These terms are not bound by their historic use, but rather (Rémond argued) serve as useful guides to understanding French conservatism today.

Gaullism, for example, with both its populism and its reliance on the authority of a charismatic leader, is classified as bonapartist. Social conservatism, meanwhile, with its affinity for the Church and for tradition, comes in under legitimism. And economic liberalism — the bourgeois supremacy of the markets — is orleanist.

What to make of the current presidential candidate of the French right, M François Fillon? The Québécois website Dessinons les élections (“Let’s draw the elections”) sought to apply a Rémondian analysis of Monsieur Fillon in one of its weekly cartoons (by Frédéric Mérand & Anne-Laure Mahé).

Their conclusions are as follows:

Legitimism: 60%

– social conservatism

– Christian values

– order and traditionOrleanism: 30%

– economic liberalismBonapartism: 20%

– a sense of the State

– idea of the providential man with reference to de Gaulle

Of course, many now think that, due to the usual scandals, Fillon is yesterday’s man and that Macron is the man of the hour. The two are chalk and cheese. Fillon is the family man from the country, loves hunting, and clings to the values of the Church. Macron is a socialist énarque and investment banker who married one of his school teachers (twenty-four years his senior).

The elephant in the room: Madame Le Pen. The leader of the Front national will, there is almost no doubt, top the first round of the election but then, in the second round, will have to face whichever other candidate gains the next highest number of votes. Whoever that candidate is will almost certainly gain all the anti-frontiste votes and be propelled to victory and the Elysée.

At the moment, it looks like the second candidate will only have to win around 22 per cent of the vote in order to effectively gain the presidency. Such a low level of actual support is one of the things the 1962 changes to the constitution sought to prevent, but when faced with an FN candidate as in 2002 or (presumably) this year the two-round system fails to prevent this.

As usual, the conservatives are calling for change and the progressives arguing for stasis, but it remains to be seen which option France will choose.

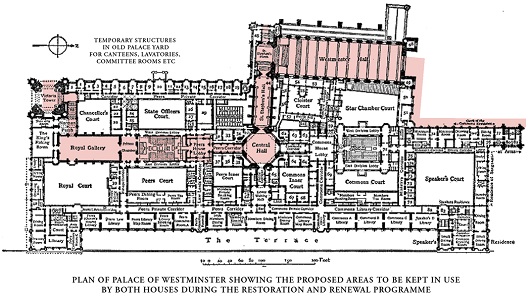

The Delarue Proposal for Parliament

Peers & MPs could still convene in the Palace during renovations

The Royal Gallery set up for temporary use as the House of Lords chamber

Credit: Anthony Delarue Associates

MPs are kicking up a fuss about the controversial proposals to shut down the entire Palace of Westminster for perhaps as long as eight or nine years. (Previously mentioned here.) The building is completely structurally sound, and on solid foundations, but the accumulation of mechanical, electrical, and technological systems over the course of the past 150 years has created a confused mess within the walls of the palace. Electrical lines compete with fibre-optic cables, telephone wires, not to mention various heating and cooling pipes, and even some lingering telegraph wires. No one’s quite sure what is what and all of it is getting older. Even just accessing it to figure out what to do requires taking the building apart — removing wood panelling, drilling through walls, etc.

Parliamentary authorities commissioned management consultants from Deloitte to come up with a number of options on how to tackle this problem, but in their Independent Options Appraisal they treated this merely as an ordinary engineering job, rather than recognising the Palace as one of the most important places in British history both medieval and modern and, importantly, one still in constant daily use.

The Joint Committee formed of members of both the Lords and Commons perhaps unsurprisingly endorsed the option Deloitte claimed was the quickest and cheapest: that the Lords, Commons, and everyone else be chucked out of the Palace entirely and that temporary accommodation be found nearby.

Further investigation by respected former minister Shailesh Vara MP suggested that Deloitte had failed to take into account that any VAT costs on this major project go back into the Treasury anyhow, and that there was a failure to account for the loss of revenue if the Lords are moved into the government-owned Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre nearby. The QE2 is a profit-making venue popular with private clients, after all, and deploying it towards full-time legislative use will mean another significant loss for the Treasury. Meanwhile, in the courtyard of Richmond House on Whitehall, £59 million would be spent on building a new chamber for the House of Commons. This would be a permanent ‘legacy’ structure even though once the renovations to the Palace are complete there would be no use for it whatsoever.

The architect Anthony Delarue, having been taken on a tour of the Palace’s working underbelly by the engineers from the Restoration and Renewal programme, came up with an alternative proposal. Looking at the structure of the House of Lords chamber and the adjacent Royal Gallery, he realised that these two rooms could be maintained and occupied, with temporary services (electricity, heating, etc.) run from external sources. This would allow the renovation team to shut down the Palace’s systems entirely and re-do them completely, while the spaces in mind would still be able to be put to use. The Commons could then meet in the Lords chamber (as the wartime precedent suggested) and the Lords could meet in the Royal Gallery. Or indeed vice versa depending on the wishes of both Houses.

The advantages of this are no need for taking up the QE2 conference centre (with consequent loss of revenue for the Treasury) and no need to waste tens of millions on a temporary-but-permanent Commons chamber in the courtyard of Richmond House. In addition, both houses would be allowed to maintain their presence in the Palace of Westminster, in accommodation suitable to the traditions of the “Mother of Parliaments”.

Of course, the Restoration and Renewal programme ran a “high level review” of Delarue’s proposals and pooh-poohed the whole idea, amazingly claiming that it would probably cost £900 million more than the Deloitte option the Joint Committee preferred. Anthony Delarue has now written some comments responding to this review, pointing out that it relies on outrageously pessimistic estimates of timing, assumptions that are beyond the worst-case scenarios of project management.

MPs were expected to debate the matter last month, but the campaign organised by Sir Edward Leigh MP and Shailesh Vara MP has found considerable support among other Members of Parliament and it is believed the powers that be are looking for a delay. The Government have promised a free vote on the issue when it comes up for debate, which may very well be before the end of February.

● Anthony Delarue Proposal

● Deloitte Independent Options Appraisal

● Joint Committee Report

● High Level Review of Delarue Proposal

● Anthony Delarue Response to High Level Review

Credit: Anthony Delarue Associates

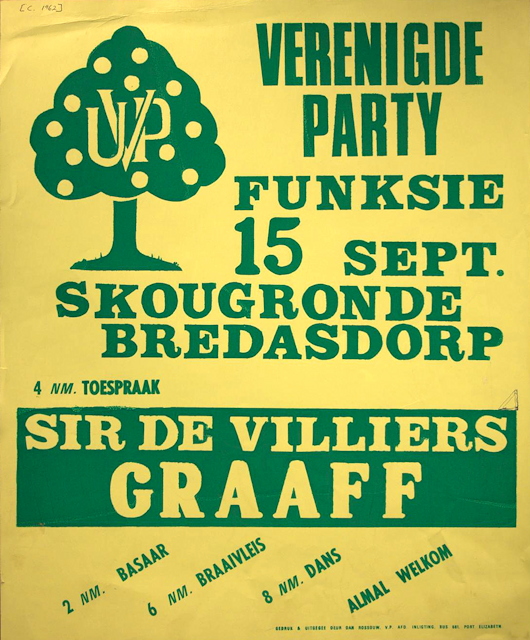

Party in the Overberg

Alongside a bazaar, a braai, and dancing, a speech by Sir De Villiers Graaff is the selling point of this poster advertising a United Party (Verenigde Party) get-together in the beautiful Overberg region of the Cape.

“Sir Div” was the inheritor of one of only twelve South African baronetcies and led his party from 1956 until 1977 when it merged with the Democratic Party of verligte ex-Nationalists to form a new entity.

The broadly centrist party had lost power to the republican Nats (creators of apartheid) in 1948, and suffered splits that led to the creation of the Liberal Party and the United Federal Party in 1953, the National Conservative Party in 1954, and the Progressive Party in 1959.

The party’s emblem was a happy little citrus tree.

Nick and Miriam

The Lib Dems are justifiably an unpopular lot, but their obvious defects aside one can find time to love a bare few of their number.

Sir Ming — sorry, Lord Campbell of Pittenweem now — will always be my favourite Liberal leader: captain of the Scotland team at the 1966 British Empire & Commonwealth Games, Chancellor of the University of St Andrews, as well as my MP when I lived in the Kingdom of Fife.

The prize for favourite unsuccessful Liberal candidate goes to my former tutor, the arch-monarchist Rt Rev Dr Ian C Bradley, who contested Sevenoaks for the Liberals at the February 1974 general elections. (Incidentally, the seat was later contested by Tim Stanley for the Labourites in 2005.)

But I also have to confess I’ve always rather liked Nick Clegg. While the overwhelming majority of politicians are mediocre, he enjoys the élan of a continental mediocrity rather than a more English strain. In fact, Nick Clegg’s incredibly boring and voter-friendly English name disguises a polychromatic background. On his father’s side he is descended from the Engelhardts (a Russian noble family of Baltic-German ancestry) and is indeed a distant cousin of Count Michael Ignatieff, leader 2009-2011 of Canada’s Liberal Party, while his mother is a Hollander of the Dutch East Indies. No surprise then that Clegg claims fluency in French, Dutch, German, and Spanish. What a waste he was as DPM: he would’ve made a decent Foreign Secretary.

I suppose as an inveterate cosmopolitan myself I must subconsciously find some strange affinity with this ex-leader of the Lib Dems. But chatting with my friend Roland the other day we decided that really the best thing about Clegg is not the man himself but his spectacular wife.

Being stylish, beautiful, Spanish, and Catholic, Miriam González Durántez manages to combine many wonderful and desirable qualities. She is also very obviously in charge. “Oh, Nicky darling, you are agnostic? How cute. The children are being raised Catholic.” And she looks great in Liberal yellow — not a colour every woman can pull off.

If the Lib Dems are looking to increase their vote-share and return to former prominence they could do worse than making Miriam leader. But then — with the exception of Leeds North West with its Chestertonian pro-life real-ale-and-trams-obsessed Lib Dem MP — this is a party unlikely to ever capture the Cusackian vote.

The End of Liberalism

Viktor Orban on the end of the liberal age and the threat to Europe

In a speech to supporters at the Fidesz party’s fourteenth annual Kötcse picnic, the Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán has claimed that the refugee crisis is a portent of the end of “the era of liberal babble”. The current “identity crisis” of liberalism, Orbán argued, presented both “huge risk” and “a new opportunity” to return to Christian and communal identities.

Mr Orbán said that the dominant liberal ideology had weakened Europe while preserving its wealth. “The most dangerous combination known in history is to be both rich and weak,” he argued. “It is only a matter of time before someone comes along, notices your weakness, and takes what you have.”

“The liberal philosophy is a result of a Europe which is weak and which also wants to protect its wealth; but if Europe is weak, it cannot protect this wealth.”

Mr Orbán also attacked the liberal imperialism of military intervention, asserting it has been based on fundamental hypocrisy and simplistic Manichean thinking: (more…)

The Legacy of 1916

The commemoration of the 1916 rebellion takes place at Arbour Hill prison, where the earthly remains of the executed leaders of the Easter Rising were laid in a pit by the British military authorities. Some of the rebellion’s leaders who did not face the firing squad, most prominently Éamon de Valera and Countess Markievicz, founded Fianna Fáil ten years later in 1926.

Micheál Martin’s address is presented here without comment.

Every state should take time to commemorate and celebrate the people and events of their founding. This commemoration is organised by Fianna Fáil the Republican Party, but we come here as Irish men and women to fulfil our responsibilities to the great generation of 1916.

After 97 years their deeds resonate even more than ever. They saw an Ireland which should not accept limits on its future. They committed everything to the vision of a country with the right to shape its own destiny.

As we quickly approach the centenary of the Rising no one can doubt that the Irish people see the men and women of 1916 as noble and courageous. No one can question their central place in our history. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Articles of Note: 27 January 2025 January 27, 2025

- Spooks’ Crown January 23, 2025

- Jesuit Gothic January 23, 2025

- Christ Church December 29, 2024

- A Christmas Gift from the Governor December 24, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories