Paris

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

30 mai 1968

The events of May 1968 have been fetishised by the romantic radical left but ended in the triumph of the popular democratic right. Battered by two world wars, France had enjoyed an unprecedented rise in living standards since 1945 — especially among the poorest and most hard-working — and a new generation untouched by the horrors of war and occupation had risen to adulthood (in age if not in maturity). The ranks of the middle class swelled as more and more people enjoyed the material benefits of an increasingly consumerised society, while those left behind shared the same aspirations of moving on up.

Like any decadent bourgeois cause, the spark of the May events was neither high principle nor addressing deep injustice but rather more base impulses: male university students at Nanterre were upset they were restricted from visiting female dormitories (and that female students were restricted from visiting theirs). The ensuing events involved utopian manifestos, barricades in the streets, workers taking over their factories, a day-long general strike and several longer walkouts across the country.

The French love nothing more than a good scrap, especially when it’s their fellow Frenchmen they’re fighting against. Working-class police beat up middle-class radicals but for much of the month both sides made sure to finish in time for participants on either side to make it home before the Métro shut for the evening. But workers’ strikes meant everyday life was being disrupted, not just the studies of university students. When concessions from Prime Minister Georges Pompidou failed to calm the situation there were fears that the far-left might attempt a violent overthrow of the state.

De Gaulle himself, having left most affairs in Pompidou’s hands, finally came down from his parnassian heights to take charge but then suddenly disappeared: the government was unaware of the head of state’s location for several tense hours.

It turned out the General had flown to the French army in Germany, ostensibly to seek reassurance that it would back the Fifth Republic if called upon to defend the constitution. De Gaulle is said to have greeted General Massu, commander of the French forces in West Germany, “So, Massu — still an asshole?” “Oui, mon général,” Massu replied. “Still an asshole, still a Gaullist.”

The morning of 30 May 1968, the unions led hundreds of thousands of workers through the streets of Paris chanting “Adieu, de Gaulle!” The police kept calm, but the capital was tense and there was a sense that things were getting out of hand. Pompidou convinced de Gaulle the Republic needed to assert itself.

Threatened by a radicalised minority, de Gaulle called upon the confidence of the ordinary people of France. At 4:30 he spoke on the radio briefly, announcing that he was calling for fresh elections to parliament and asserting he was staying put and that “the Republic will not abdicate”.

Before the General even spoke some his supporters (organised by the ever-capable Jacques Foccart) were already on the avenues but the short four-minute broadcast inspired teeming masses onto the streets of central Paris, marching down the Champs-Élysées in support of de Gaulle.

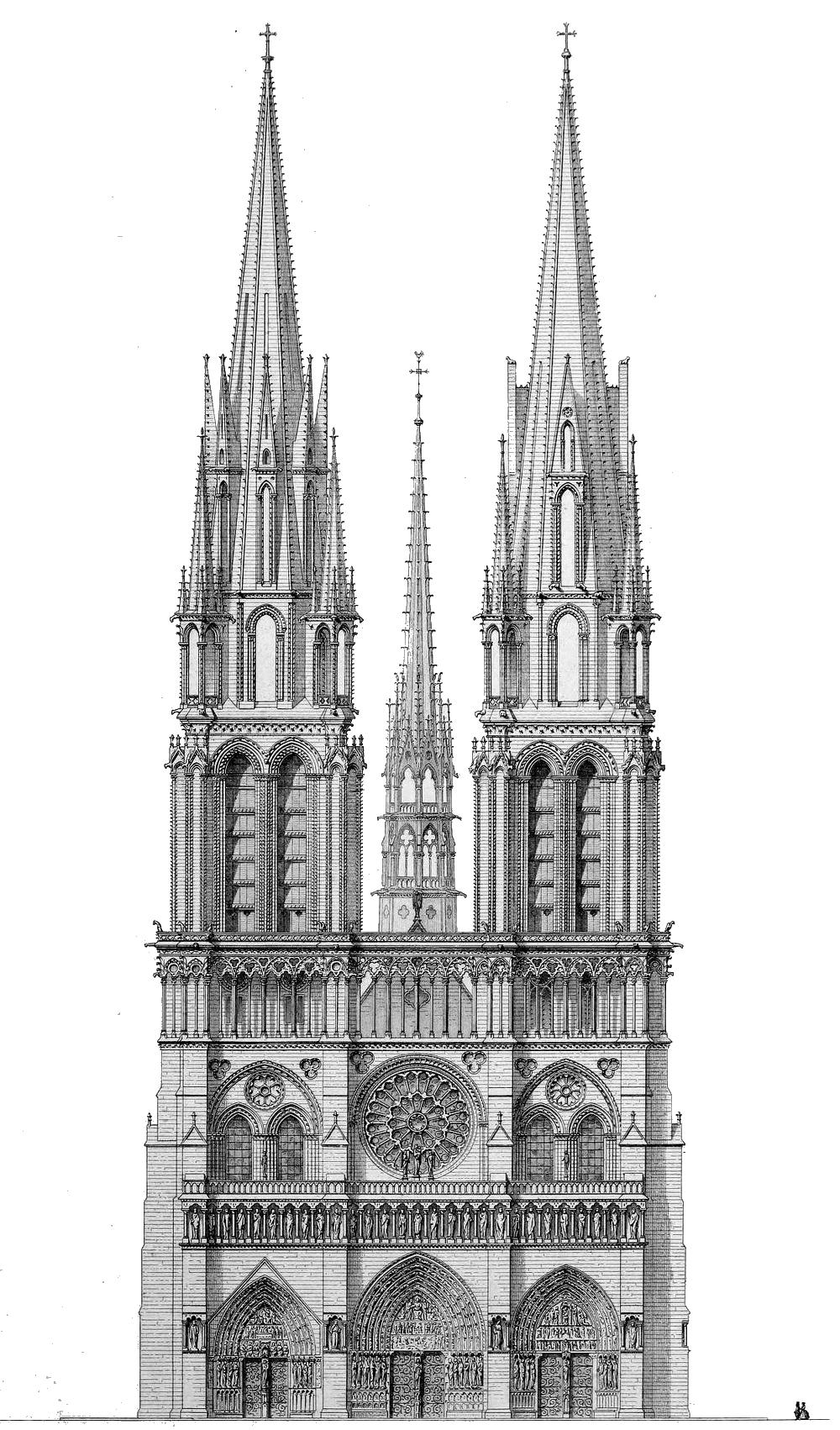

Notre-Dame de Paris

Eugène Viollet-le-Duc

1844

Haussmanhattan

Paris and New York are two cities radically different in design and character, but they are smashed together in this little project from architect Luis Fernandes.

‘Haussmanhattan’ is a portmanteau of Baron Haussmann, the Prefect of the Seine whose reconfiguration of the French capital made it the Paris we know today, and Manhattan, the most renowned of New York City’s five boroughs.

Haussmann’s plan of broad boulevards and radial avenues is a far cry from the artless Commissioners’ Plan of 1811 which created the unforgiving city blocks that colonised the entire island of Manhattan ad infinitum.

The contrast only makes the pick-and-mix Fernandes has confected all the more fun/ridiculous/interesting.

The slums of the Louvre

We are so used to the now-familiar image of the palais du Louvre — with its central wing and flanking arms wide open to the Jardin des Tuileries — that it’s easy to forget just how recent a creation this ensemble is. The palace began as a square chateau expanding upon the site of the medieval citadel. The Tuileries it eventually stretched towards was then an entirely separate palace. In-between the Louvre and the Tuileries was a whole neighbourhood of buildings, streets, alleyways, and squares.

Henri IV built the grande galerie on the banks of the Seine connecting the Old Louvre to the Tuileries by 1610, but the Louvre we know today really only came together under Napoleon III in the 1850s.

Until that point, a slum was built right up to the walls of the Palace, and even within the old courtyard. Balzac, predicting that one day all this would be cleared, noted the slum with amusement as “one of those protests against common sense that Frenchmen love to make”. (more…)

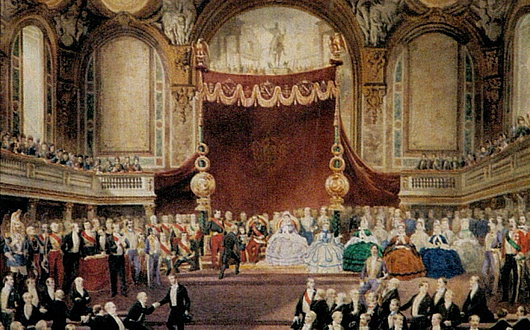

Evolution of a Napoleonic Parliament

The Salle des états in the Palais du Louvre

Among the numerous rituals of the ordinary visitor’s pilgrimage to Paris — trip up the Eiffel Tower, lunch at a tourist-trap café — braving the teeming hordes in the Louvre to view da Vinci’s ‘Mona Lisa’ ranks near the top. What very few of the camera-toting hordes realise is that they are shuffling through the room that once housed France’s parliament. The history of the Palais du Louvre is long, exceptional, and varied.

Originally built as a stern castle in the 1190s, the Louvre’s secure reputation led Louis IX to house the royal treasury there from the mid-thirteenth century. Charles V enlarged it in the fifteenth century to become a royal residence, while François Ier brought the grandeur of the Renaissance to the Louvre — as well as acquiring ‘La Gioconda’. In 1793, amidst the revolutionary tumult, part of the palace was opened to the public as the Musée du Louvre, but the Louvre has always housed a variety of institutions — the Ministry of Finance didn’t move out until 1983.

Napoleon III took as his official residence the Tuileries Palace which the Louvre was slowly enlarged towards over the centuries to incorporate. The Emperor needed a parliament chamber close at hand so he could easily address joint sittings of the Senate and the Corps législatif (as the lower house was called during the Second Empire) which opened the parliamentary year. By doing so at his residence, the Bonaparte emperor was following the example left by his kingly Bourbon predecessor Louis XVIII. (more…)

France Marches for Marriage

Led by a provocative comedian, a gay atheist, and a socialist teacher, protest against same-sex marriage draws one million

As many as a million protesters descended upon Paris from every corner of France today to demonstrate their opposition to the Socialist government’s plans to introduce same-sex civil marriage. The Prefecture of Police estimates at least 380,000 participated in the three marches from different starting points that converged at the Champs de Mars in front of the Eiffel Tower. Organisers, however, set up counting stations and claim that, by 7:30pm tonight, over one million protestors had joined the march.

Volunteers charted more than eight hundred vehicles to bring protestors to Paris, while six TGV high-speed trains were reserved for demonstrators. “Had the conditions for chartering trains not been as stringent,” an organiser told Le Figaro “the number could easily have been double.”

“In the freezing cold,” Le Figaro reports, “young, old, and families with children were trying to keep warm waving thousands of pink flags to the jerky rhythm of techno music.”

The entire workforce of the Directorate of Public Order & Traffic was called out to handle the massive demonstration, which forced a Paris Saint-Germain football match to be brought forward. Police believed it would be impossible to secure the area around the Parc des Princes stadium when hundreds of thousands of protesters were expected in the centre of the French capital.

The protest today was organised by the eccentric comedian Frigide Barjot, founder of the Collectif pour l’humanité durable, joined by gay atheist Xavier Bongibault of the association Plus gay sans mariage (“More Gay Without Marriage”), and Laurence Tcheng of La gauche pour le mariage républicaine (“The Left for Republican Marriage”).

The unlike troika claim to have launched “a guerrilla war” against the current Socialist Party government’s proposed same-sex civil marriage legislation. Avoiding the mainstream media, ‘Team Barjot’ went direct to supporters through social media such as Facebook and Twitter, and, countering the government’s branding of same-sex civil marriage as “Mariage pour tous”, named their protest “Le Manif Pour Tous” (‘The Protest for All’), asserting that all children have a right to a mother and father.

If opinion polls are to be believed, the campaign against the proposed law seems to be changing perceptions. From 2000 to 2011, polls showed a steady rise in support for same-sex marriage. In 2012, this percentage began to decline; support for allowing same-sex couples to adopt also fell. Meanwhile, polls claim that 69% prefer same-sex marriage be put to a referendum. (more…)

A Place in Paris

With a view over the Place des Victoires

If you’re in the market for a little place in Paris, centrally located, Knight Frank has got just the thing for you. Admittedly, it’s only a wing of a larger hôtel particulier on the Rue Vide-Gousset, but it has an enviable view over the Place des Victoires. Mind you, I’ve always been of two minds about the Place des Victoires. I’m not particularly a fan of Louis XIV, whose somewhat silly equestrian statue presides foppishly over the centre of the circus: I’ve always blamed him for the French Revolution, failing to heed Margaret Mary Alacoque’s warnings and all that. But the statue’s only been there since 1828, so perhaps it can be replaced with something better in a suitably classical style. (more…)

The Architecture of Immaturity

Have you ever come across the French Ministry of Culture on the Rue Saint-Honoré? It’s a perfect example of the architecture of immaturity. The government ministry was formerly strewn across nineteen different sites throughout Paris. The decision was made to consolidate their offices in one place, and the suitably central location near the Palais Royal was chosen.

The main building on the site is a handsome building from the late nineteenth-century or at the latest 1900s, with a modern 1960s office building stuck behind it. The Ministère chose architect Francis Soler to “unify” the buildings into one. At first, this was meant to be done solely through an interior reorganisation, but Soler decided to add a strange grille to the façade. (more…)

Nobility and Dignity at the Café Valois

Farewell, O good old days! Farewell, O affable visage of the proprietor and smiling and respectful reception of the waiters! Farewell, O solemn entries of the Café Valois’ dignified customs, which people were curious to see. Such was the case with the Knight Commander Odoard de La Fere’s arrival.

At exactly noon, the canon of the Palais-Royal heralded his arrival. He would appear on the threshold and pause for a moment to sweep the salon with an affable and self-assured gaze as someone eager to practice a longtime custom. His right hand pressing firmly on the white and blue porcelain handle of his cane, he threw his old faded brown cape over his shoulder with a swing of his left hand. No one ever snickered at this, since not even the most elegant mantle with golden fleur-de-lys embroidery was ever thrown back with a more distinguished movement.

In 1789 the former steward of the Prince of Conti ran the Café Valois; it was rather devoid of political colour and local flavor at that time.

Among the frequenters of the place, standing out by his noble manners, stately demeanor and wooden leg, was the Chevalier de Lautrec. He was from the second line of that family, an old brigadier of the king’s army, a Knight of Malta, of Saint Louis, of Saint Maurice and of Saint Lazare.

The Chevalier de Lautrec was a middle-aged man who lived a modest, though very dignified life on his small pension. Though he rarely appeared in society, he could be seen most often at the Palais Royal and the Café Valois. He was a very cultured mind and an assiduous reader of all the newspapers.

Deprived of his pension overnight, it was never known what the Chevalier de Lautrec lived on at a time when it was so difficult to live, and so easy to die. But here we have something that sheds at least a dim light on this mystery.

One morning after finishing a very modest breakfast in the Café Valois, as was his custom, the Chevalier de Lautrec rose from his table, chatted with all naturalness with the proprietress, who stood behind a counter, bid good-day to the master of the café with a slight gesture of the eyes, and walked out majestically saying nothing about the bill. (more…)

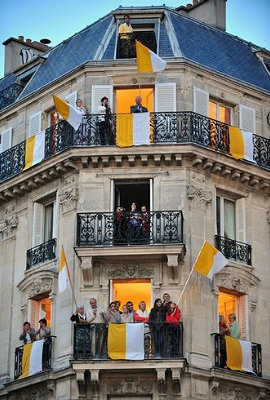

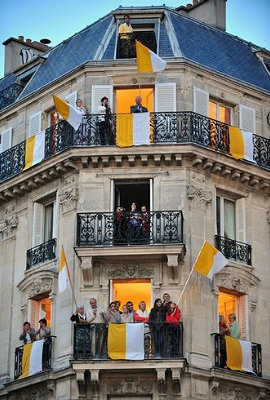

Le Pape à Paris

While Benedict XVI is currently in the headlines for his visit to the Holy Land, here is a translation into French by Béatrice Bohly of my piece on Benedict’s visit to Paris last year.

La devise de la ville de Paris, Fluctuat nec mergitur est parfaitement appropriée: « Battue par les flots, elle ne sombre pas ». Difficile de trouver des mots plus aptes à décrire la barque de Pierre, dont le Saint-Père, le pape, a passé ces deux jours dans la capitale française. Depuis des temps immémoriaux, la France a été considérée comme « la fille aînée de l’Eglise », son siège de primauté de Lyon ayant été établi au cours du deuxième siècle et Clovis, son premier roi chrétien, ayant reçu le baptême en 498. Mais à côté de 1.500 ans de christianisme, au cours des deux derniers siècles, la France, a également servi de fonds baptismaux à la révolution et à la rupture – dans l’esprit-même de ce premier “non serviam” (phrase attribuée à Lucifer, refusant de servir Dieu, ndt) .

La devise de la ville de Paris, Fluctuat nec mergitur est parfaitement appropriée: « Battue par les flots, elle ne sombre pas ». Difficile de trouver des mots plus aptes à décrire la barque de Pierre, dont le Saint-Père, le pape, a passé ces deux jours dans la capitale française. Depuis des temps immémoriaux, la France a été considérée comme « la fille aînée de l’Eglise », son siège de primauté de Lyon ayant été établi au cours du deuxième siècle et Clovis, son premier roi chrétien, ayant reçu le baptême en 498. Mais à côté de 1.500 ans de christianisme, au cours des deux derniers siècles, la France, a également servi de fonds baptismaux à la révolution et à la rupture – dans l’esprit-même de ce premier “non serviam” (phrase attribuée à Lucifer, refusant de servir Dieu, ndt) .

Ce fut le penseur français Charles Maurras – lui-même non-catholique jusqu’à la fin de sa vie – qui a conçu de la notion que (depuis la révolution) il n’y avait pas une France mais deux : le pays réel et le le pays légal. La vraie France, catholique et droite, contre la France officielle, irreligieuse et artificielle. Tout comme Maurras différenciait les deux visions de la France, nous, dans le monde d’expression anglaise, savons que l’Angleterre est vraiment un pays catholique qui souffre d’un interregnum de quatre-siècle (de même que l’Ecosse, et l’Irlande, et l’Amérique, et le Canada, et l’Australie…). Nous aimons nos patries mais nous savons qu’elles ne sont pas vraiment elles-mêmes – elles ne reflètent pas vraiment cette idée de leur essence – jusqu’à ce qu’elles jouissent de la plénitude de la communion chrétienne.

The Pope in Paris

Benedict XVI brings a message of love & hope to the City of Light

It is wholly appropriate that the motto of the city of Paris is Fluctuat nec mergitur: “Tossed by waves, she does not sink”. It would be hard to find better words to describe the Barque of Peter, whose Holy Father the Pope has spent the past two days in the French capital. From time immemorial, France has been described as “the eldest daughter of the Church”, its primatial see of Lyons established in the second century and Clovis, its first Christian king, receiving baptism in 498. But alongside the 1,500 years of Christianity, France has, for the past two centuries, also been a font of revolution and disruption — the very spirit of that first “non serviam“.

It is wholly appropriate that the motto of the city of Paris is Fluctuat nec mergitur: “Tossed by waves, she does not sink”. It would be hard to find better words to describe the Barque of Peter, whose Holy Father the Pope has spent the past two days in the French capital. From time immemorial, France has been described as “the eldest daughter of the Church”, its primatial see of Lyons established in the second century and Clovis, its first Christian king, receiving baptism in 498. But alongside the 1,500 years of Christianity, France has, for the past two centuries, also been a font of revolution and disruption — the very spirit of that first “non serviam“.

It was the French thinker Charles Maurras — not himself a Catholic until the very end of his life — who conceived of the notion that (since the Revolution) there was not one France but two: le pays réel and le pays legal; The real France, Catholic and true, versus the official France, irreligious and contrived. Just as Maurras differentiated the two visions of France, we in the English-speaking world know that England is truly a Catholic country that is suffering from a four-century interregnum (and so with Scotland, and Ireland, and America, and Canada, and Australia…). We love our homes but we know they are not truly themselves — they do not truly reflect that idea of their essence — until they enjoy the fullness of Christian communion.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories