Other Modern

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The Other Modern in Jewish Amsterdam

Jacobus Baars’ Synagoge Oost, Linnaeus Street

There were few places where architecture’s competing forms of modernism overlapped more than the Netherlands in the 1920s. Traditionalists like Kropholler, De Stijl’s Oud, Rationalists like van der Vlugt and Duiker, and the versatile Dudok built alongside the work of the capital’s eponymous ‘Amsterdam school’ style.

The influence of the great Dutch architect Pierre Cuypers — Holland’s Pugin — might be inferred as the progenitors of the Amsterdam school (De Klerk, van der Mey, and Kramer) all studied or worked in the firm of Cuypers’ nephew Eduard.

The Dutch capital’s take on the brick expressionism originated among its Hanseatic neighbours but was sufficiently distinct to merit its own name. Architect Jacobus Baars (1886-1956) deployed the style to great effect in the work he did for Amsterdam’s then-flourishing Jewish community.

Baars designed the 1928 Synagoge Oost (East Synagogue) on Linnaeusstraat (Linnaeus Street) in the Transvaalbuurt neighbourhood that was developed in the first decades of the twentieth century.

Dutch sympathies in the then-still-recent Anglo-Boer War are obvious from the naming of local streets and squares (and, indeed, the district) after Afrikaner places, battles, and statesmen.

The architect placed the building at an angle so that the entrance could face on to Linnaeusstraat while the holy ark containing the Torah scrolls faced Jerusalem, skilfully filling in the rest of the site with clergy and school structures ancillary to the sanctuary and congregation. (more…)

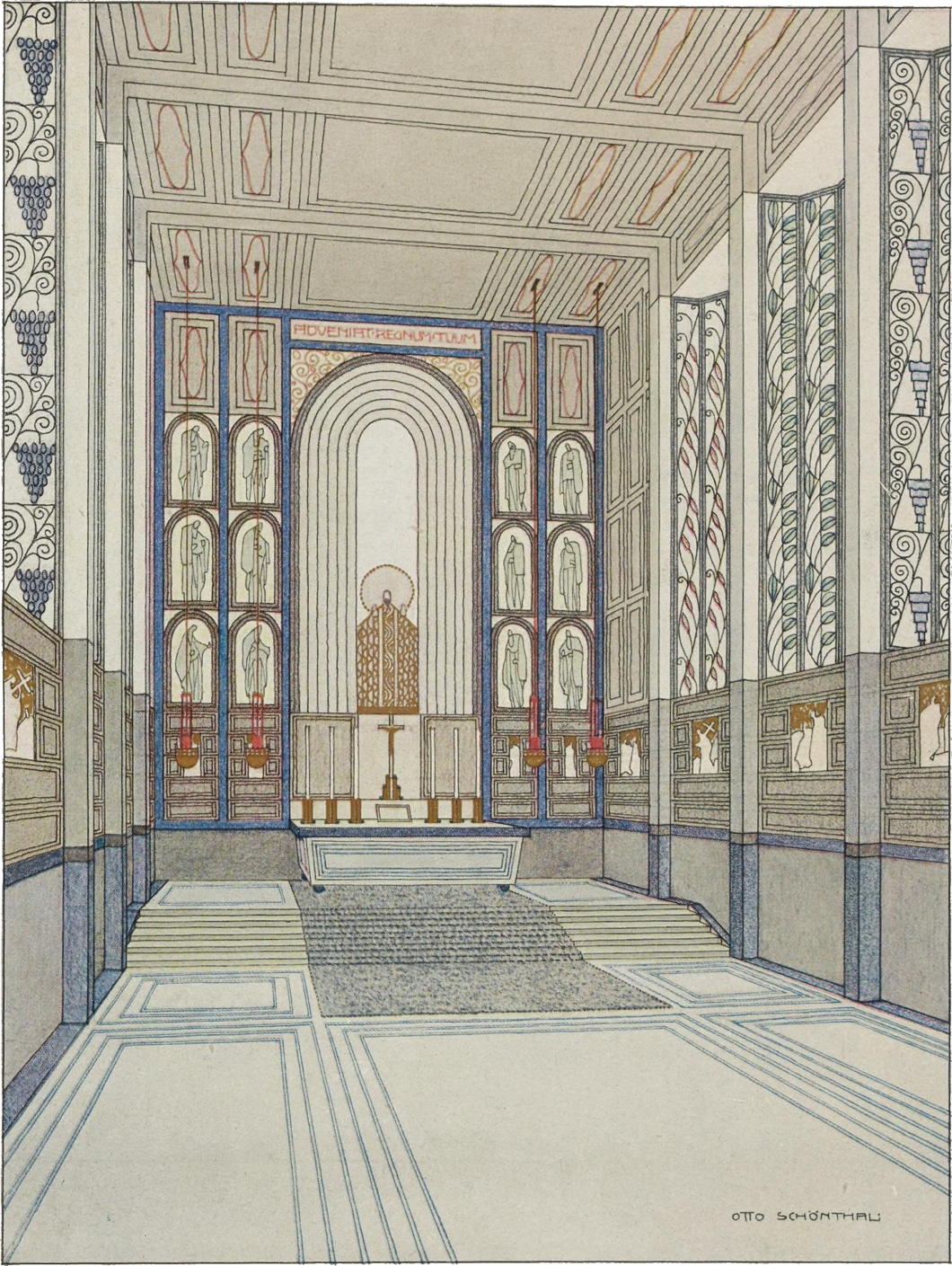

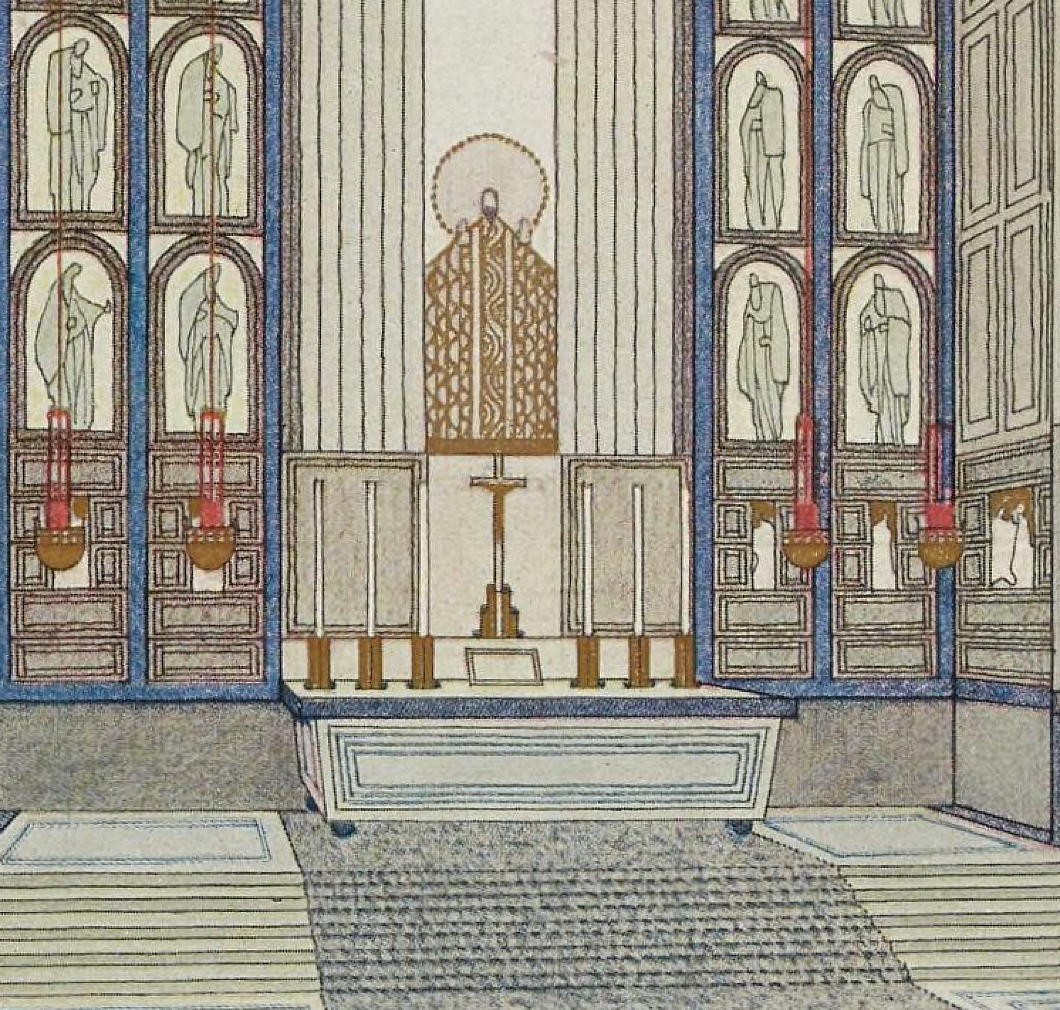

The Other Modern: Otto Schöntal

The Viennese architect Otto Schöntal was a student of Otto Wagner at the Academy of Fine Arts and exhibited this project for a Schloßkapelle in the periodical Moderne Bauformen in 1908.

It combines a simplicity of form with greater complexity in its decoration but like the work of many of the more mid-ranking architects of the Secession it comes across as a bit rigid and angular despite a certain freeness in its design.

F.X. Velarde: Forgotten & Found

Many of the architects of the “other modern” in architecture were forgotten or at least neglected once the craft moved in a more avant-garde direction.

The British Expressionist architect F.X. Velarde who produced a number of Catholic churches in and around Liverpool in the interwar period and beyond is the subject of a new book from Dominic Wilkinson and Andrew Crompton.

There will be a free online lecture tomorrow on ‘The Churches of F. X. Velarde’ given by Mr Wilkinson, Principal Lecturer in Architecture Liverpool John Moores University. Further details are available here.

The book is available from Liverpool University Press with a 25% discount through the Twentieth Century Society. (more…)

The ‘Other Modern’ in Portugal

Guarda, Portugal; 1939–1942

[A] core aspiration can be discerned that runs through the entire [architectural] output of the “Estado Novo”, particularly from the second half of the 1930s. It is a catchphrase, never defined with absolute clarity and therefore tested by approximation, trial and error: the demand for a national modern style, a construction style that was at the same time contemporary and suited to the locality and/or specificity of the country. This agenda accommodated various formulations, depending on the evolution of the regime itself, the type of public building in question, the place for which it was intended, the profile of the people responsible for its appraisal and the margin granted to the architect-designer. […]

Salazarism never upheld anachronism or the practice of an archaeological type of architecture. It did not reject modernity entirely, but disliked disaggregating, standardising, stateless foreignness, embodied in its view by the architectural abstractionist internationalism (dubbed “boxes”). An alternative modernity was thus aspired to and achieved; far from being an exclusive diktat of the state, this idea of an alternative modernity pervaded the discourses of the timid specialist press, the opinions generally expressed by the civil society and the dilemmas of the architects themselves.

RIHA Journal 133, 15 July 2016

See also: The Other Modern

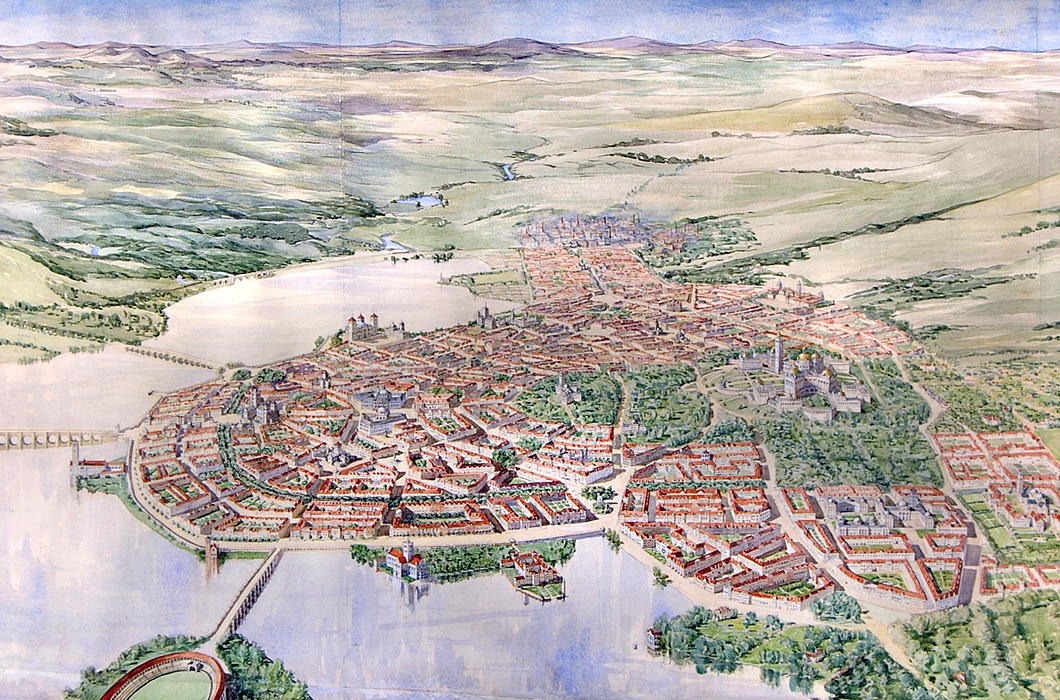

The most beautiful city never built

Ernest Gimson’s Canberra

Whenever I’m in in Westminster Cathedral, I feel obliged to nip in to and say a prayer in the chapel dedicated to St Andrew. The apostle is my patron many times over: in addition to being my name-saint, he is the patron of the university, the town, and the country in which I spent four luxurious years. His is one of the most finely decorated chapels in the cathedral, and boasts a beautiful mosaic depiction of the ‘Auld Grey Toun’ above the arms of the donor, the 4th Marquess of Bute. (His father, the eccentric 3rd Marquess, had been Lord Rector of the University of St Andrews.)

Stumbling upon the genial Cathedral Historian, Patrick Rogers, the other day, he shared with me that the stalls and kneelers in St Andrew’s Chapel are widely considered the finest works of arts-and-crafts furniture design in all of Great Britain. They are the creation of a man I had never heard of: the craftsman, designer, and architect Ernest Gimson.

An unfamiliar name is always a potential new avenue of knowledge down which to saunter, and so it proved with Ernest Gimson. His talent at furniture is undoubted but, given my obsession with architecture, it was instead that field of his expertise which particularly drew me in. It was then that I discovered his submission for the 1911-1912 Australian Federal Capital Competition.

The British colonies in Australia federated in 1901, and the dispute between Sydney and Melbourne as to which would be the capital of the youthful nation was settled by agreeing to build a new planned city within New South Wales (the state Sydney is in) but not more than 200 miles from Melbourne.

Ten years later, an international competition was announced to determine the design for this new capital being created ex nihilo on the banks of the Molonglo river, which was given the name of Canberra.

Of the 137 entries received, many of them were very handsome, but some of them were frankly awful. Rather than have a team of architects, artists, or urbanists choose the winning design, the Minister for Home Affairs, Mr King O’Malley, was the sole decision-maker.

He eventually chose the plan submitted by the Chicago architect Walter Burley Griffin, awarding a second prize to Eliel Saarinen of Finland, with third prize going to Alfred Agache of Paris.

The design I would have chosen, however, was Ernest Gimson’s.

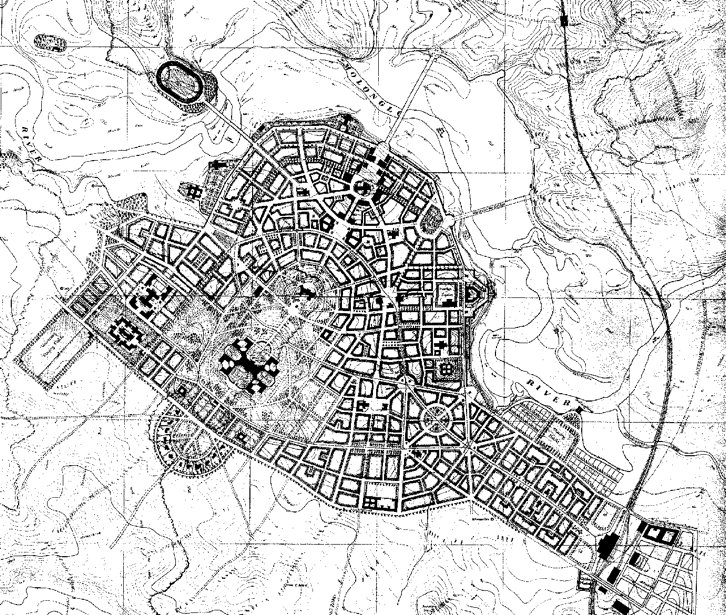

Gimson designed a compact capital city of 25,000 inhabitants that would be able to support itself based on neighbouring farms and small-scale industry.

The city is entirely concentrated along the south bank of an artificial lake and centred on a wooded park containing Kurrajong Hill and Camp Hill, with the streets of the city radiating down from there toward the lakeside.

Kurrajong Hill, with its dominating position over the city, was selected for the Houses of Parliament, with eight departmental buildings surrounding it on a lower terrace.

Official residences for the Governor-General and Prime Minister are located nearby, each with six acres of private grounds.

The State Hall is located atop the adjacent, slightly lower, Camp Hill, with the Printing Office and Mint located at either side, where the park ends.

North-west of Kurrajong is the City Hall, flanked by the Courts of Justice, with its main entrance facing towards the central park.

On a small hill nearby is the University, its double-domed central block surrounded again by ancillary buildings on a lower terrace. Playing fields are allotted nearby.

The market is located on the east side “with a covered arcade for the stalls enclosing an open square”, alongside a market house and technical colleges.

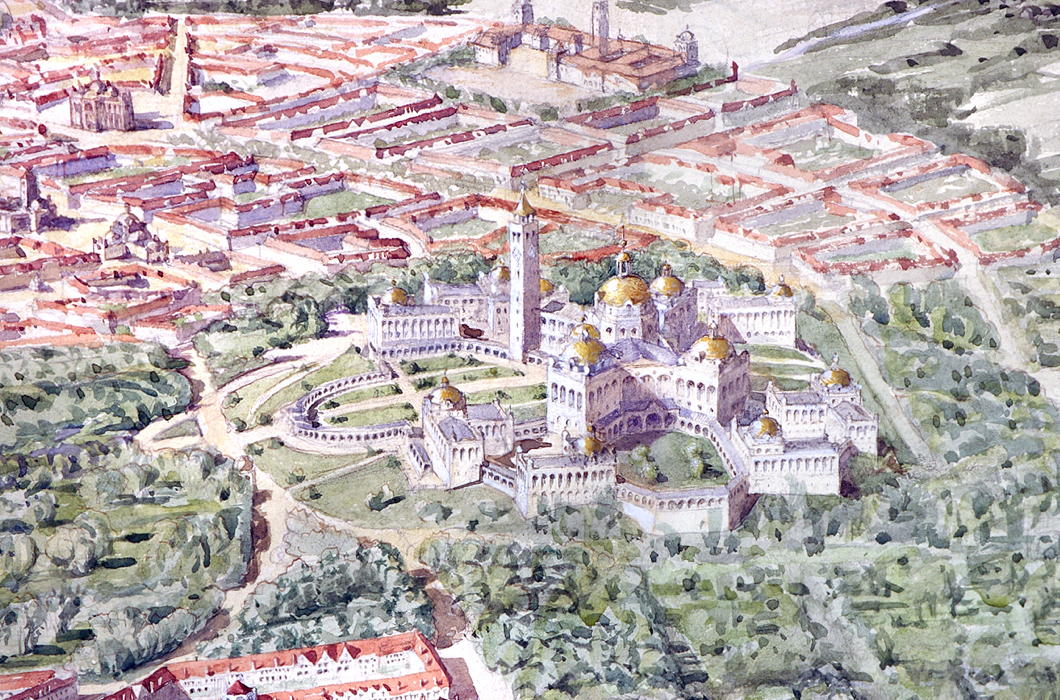

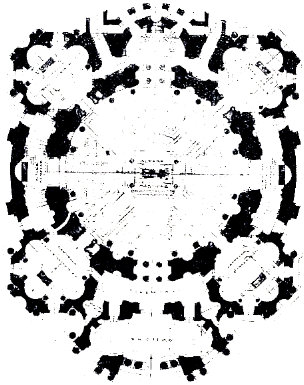

The Cathedral rises from the center of the city proper and forms an axis with the State Hall on Camp Hill and the Houses of Parliament atop Kurrajong.

At the near-midpoint of the street connecting the Cathedral to the State Hall, a public square is flanked by a National Art Gallery and Library. Around the Cathedral itself are the National Theatre and the General Post Office.

A stadium is located on the north side of the lake, connected to the city by a bridge, and further provision is made for siting barracks, gas works, a power station, cattle market, and other necessities.

Buildings would chiefly be faced in a light-coloured local stone which gives the plan, deeply influenced by tradition, both a brightness and a more vernacular feel.

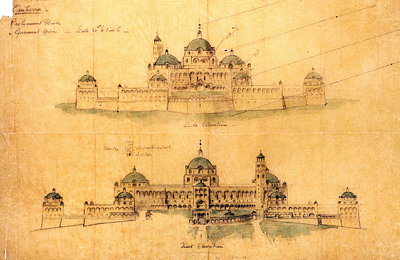

To discuss the design of the buildings is tricky: this proposal is an initial plan and, had it been selected, the architect would have had more time to then further refine what he was proposing.

The Houses of Parliament, with their eccentric X-footprint, are a curious conglomeration and not quite right. There seem to be a surfeit of towers that look too similar to one other.

But the Cathedral — my favourite part of Gimson’s plan — is a magnificent creation with an assertive central crossing tower that doubtless would become the visual focus of the city.

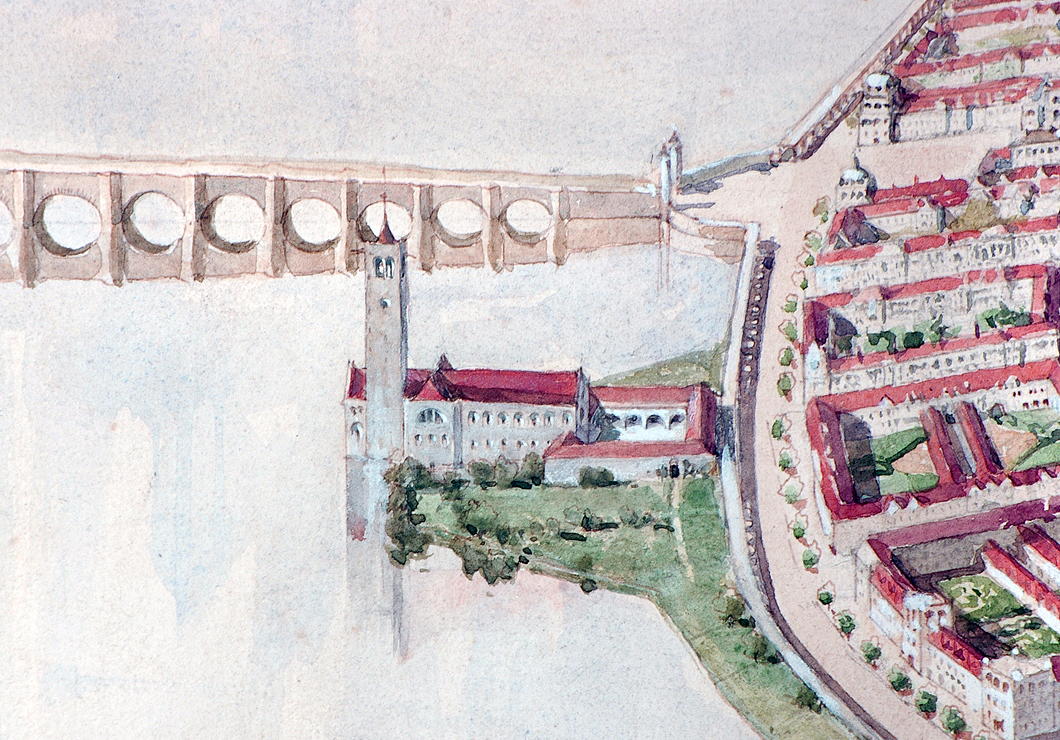

The embankment, with its long, generous, 20-foot-deep arcade providing “sheltered walk in hot and wet weather”, is both picturesque and useful.

“While screening in some measure the near part of the lake from the ground floor windows of the houses opposite,” the arcade, Gimson notes, “would enhance rather than diminish, the interest of the wider views.”

Indeed, it provides a useful transition point from lakeside to the rise of the buildings.

The architect’s layout of streets, public spaces, and important buildings, meanwhile, shows the influence of the aesthetic principles of the Austrian urbanist Camillo Sitte, now unjustly neglected since being contemptuously derided by Le Corbusier and other leading modernists.

Gimson’s Canberra is an unpretentious city: its lack of grandeur is what most likely secured its rejection by the fathers of the young and vigorous nation, who were keen to impress. Burley Griffin provided them with a plan redolent of modernity and progress, but marred by fading modishness.

The Gimson plan would have provided Australia a beautiful modern capital city with a design deeply rooted in tradition, and with appropriate consideration of locality and climate. One can imagine that, as the course of history continued, ‘Old Canberra’ would have formed a handsome and much-loved heart of an ever-growing city.

The humane, natural traditionalism of Gimson’s Canberra would have made it much more popular with ordinary people than the sprawling, overly spacious modern city that Canberra is today. Still, it provides a model that urbanists of the future should be mindful of and take inspiration from.

The Other Modern in Madrid

Miguel Fisac’s Church of Espíritu Santo, Madrid

It might be difficult for some to imagine that the architect of the pagoda-like Laboratorios Jorba outside Madrid was an accomplished classicist, but, like many modern architects, Miguel Fisac began his career with more traditional works. His very first commission as an individual was to design a church for Spain’s Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (Higher Council of Scientific Research). The CISC had only been founded in 1939 and was originally housed in existing structures around Madrid. The Church of the Holy Spirit (constructed 1942–1947) was the first newly built structure for the research council, and the fact that it was an ecclesiastic building “eloquently expresses the spirit of commitment between religion and science that animated the new project” (according to the Fundacion Fisac). Around the corner from the Church of the Holy Spirit, the main headquarters of the CISC was designed by Fisac. (more…)

Politigården

The Police Headquarters, Copenhagen

One of the pleasures of the recent hit Danish television series Forbrydelsen (released in the UK as ‘The Killing’) is the occasional view it provides of Copenhagen’s police headquarters.

Politigården (lit. police-yard) is in a restrained Scandinavian modern classicism and was designed by Hack Kampmann.

It was constructed from 1918 to 1922 but Knapmann died in 1920, and his role as chief architect was assumed by his son Hans Jørgen Kampmann (whose brother Christian was also an architect).

The interior hints towards a variety of styles from Renaissance to Baroque and Art Deco, while the building rises around a large central circular courtyard roughly the same diameter as the Pantheon in Rome.

Some architectural historians consider Politigården the last neoclassical public building in northern Europe (so far, that is). (more…)

The Modern Baroque: Brasini in Parioli

The Church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary

GOOD ARCHITECTURE requires a combination of willpower, taste, and resources. This nexus used to occur quite often; instances from the Renaissance and the long nineteenth century come most easily to mind. A late twilight of this combination is found in the magnum opus of the Italian architect Armando Brasini: the Church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Rome’s swish Parioli neighbourhood.

The  church, a modern expression of the Baroque, has somewhat curious and disjointed origins. Every age has left its imprint on Rome in one way or another: the Rome of the Republic, the Rome of the Empire, the Rome of the Popes, the Rome of the Liberals, the Rome of the Fascists, the Rome of the Italian Republic. In the 1900s, it was realised that the Church had not made a significant contribution to the great architecture of Rome for some time. Worse: the more significant structures of the past century were mostly built by the government of the Sardinian kingdom that conquered Rome and gave itself the fanciful, if geographically correct, name of ‘Italy’. A new church was needed, on a monumental scale, to be the age’s contribution to the great churches of Rome. Originally, the church was to be dedicated to St. James the Greater, but as preparations increased for the International Marian Year of 1924, it was decided the cult of the Immaculate Heart of Mary would take precedence instead. (more…)

church, a modern expression of the Baroque, has somewhat curious and disjointed origins. Every age has left its imprint on Rome in one way or another: the Rome of the Republic, the Rome of the Empire, the Rome of the Popes, the Rome of the Liberals, the Rome of the Fascists, the Rome of the Italian Republic. In the 1900s, it was realised that the Church had not made a significant contribution to the great architecture of Rome for some time. Worse: the more significant structures of the past century were mostly built by the government of the Sardinian kingdom that conquered Rome and gave itself the fanciful, if geographically correct, name of ‘Italy’. A new church was needed, on a monumental scale, to be the age’s contribution to the great churches of Rome. Originally, the church was to be dedicated to St. James the Greater, but as preparations increased for the International Marian Year of 1924, it was decided the cult of the Immaculate Heart of Mary would take precedence instead. (more…)

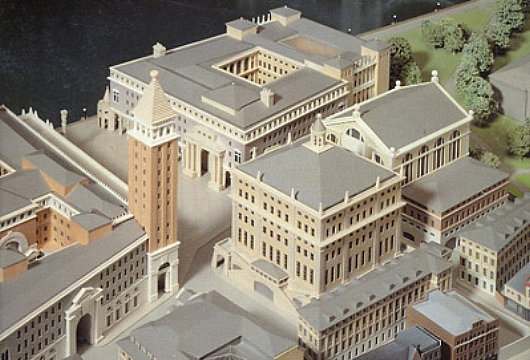

London Bridge City: The Neo-Venetian Scorned

JOHN SIMPSON AND Partners  are one of the most prominent firms promoting classical architecture and urban design in Great Britain. They are perhaps most widely known for the work they did on the Queen’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace, as well as for the rejected scheme to redevelop Paternoster Square next to St. Paul’s Cathedral. Contemporary to their ultimately unsuccessful Paternoster Square bid was another ambitious scheme, Phase Two of the London Bridge City development. For Phase Two, Simpson composed a miniature Venice-on-the-Thames complete with Piazza San Marco and ersatz campanile. There seems, however, to be something just a bit un-English about the whole project. There are numerous examples of Ruskinian Venetian buildings throughout Britain, and indeed the Commonwealth, but an entire complex of Anglo-Neo-Venetian seems a bit over-the-top. Still, one can’t deny preferring a touch of Simpson’s over-the-top Venetian to the glass-plated boredom developers usually offer the public.

are one of the most prominent firms promoting classical architecture and urban design in Great Britain. They are perhaps most widely known for the work they did on the Queen’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace, as well as for the rejected scheme to redevelop Paternoster Square next to St. Paul’s Cathedral. Contemporary to their ultimately unsuccessful Paternoster Square bid was another ambitious scheme, Phase Two of the London Bridge City development. For Phase Two, Simpson composed a miniature Venice-on-the-Thames complete with Piazza San Marco and ersatz campanile. There seems, however, to be something just a bit un-English about the whole project. There are numerous examples of Ruskinian Venetian buildings throughout Britain, and indeed the Commonwealth, but an entire complex of Anglo-Neo-Venetian seems a bit over-the-top. Still, one can’t deny preferring a touch of Simpson’s over-the-top Venetian to the glass-plated boredom developers usually offer the public.

London Bridge City, Phase Two was proposed in the aftermath of the hugely popular speech by Prince Charles in which he condemned a planned modernist addition to the National Gallery as a “monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend”. A bit of a donnybrook erupted between the architectural elite on the one hand (supporting the carbuncle) and the public on the other (supporting the Prince of Wales) and many a property developer was caught in the rhetorical crossfire. LBC’s backers decided, as an act of pragmatism, to come up with three radically different schemes in different styles and present them for consideration. (more…)

The Parliament of the Venerable Island

Geoffrey Bawa’s Sri Lankan Parliament at Kotte

CEYLON IS AN ancient island whose history spans the epochs of human existence: palaeontologists estimate it has been inhabited for over 34,000 years. A series of ancient and medieval native kingdoms have ruled this island over the centuries before foreigners from abroad decided to enter the game. The Portuguese were the first Europeans to stake a claim here, followed by the Dutch Republic. And, yes, as with almost every place of intrigue and tradition, even Ceylon belonged to the Hapsburgs at one point: from 1580 to 1640. Native kingdoms persisted nonetheless, even while European powers bickered over their own portions of the island.

It was in 1815 that the Chiefs of the Kandyan Kingdom agreed to depose their own monarch, Sri Vikrama Rajasinha, and place George III of the House of Hanover on the throne. Ceylon was united at last, and — after the end of the Kandyan Wars — the island enjoyed relative peace and prosperity during one-hundred-and-thirty-three years of British rule.

In 1948, the British granted independence to the Dominion of Ceylon. The island continued as an independent constitutional monarchy for much longer than its neighbours India and Pakistan. The rudiments of a two-party system emerged, with the United National Party bringing together the conservative, traditional element in political society, while the Freedom Party advocated non-revolutionary socialism.

The population of Ceylon, however, are a complete hodgepodge of ethnicities. The largest group are the Sinhalese, a Buddhist people constituting over 70% of the population. But at the northern end of the island, the Tamil people were dominant, even though these were split between “Ceylonian” Tamils native to the island and “Indian” or “Plantation” Tamils brought during British rule to work the large plantations. Then there are the Moors, a multiracial Muslim community of primarily Arab and Malay descent. And, of course, there are the famous Burgher people, descendants of the island’s Portuguese, Dutch, and English mixed with Sinhalese, Tamil, and Creole.

Democratically elected politicans replaced English (the intercommunal lingua franca) with Sinhala (the language of the Sinhalese majority) as the official language, abolished the Senate, severed appeal to the Privy Council and, in 1970, abolished the monarchy. The Dominion of Ceylon was renamed the Republic of Sri Lanka — the name literally means “Venerable Island”. Left-wing nationalists continually stoked tensions with the country’s conservatives, traditional elite, and minorities, and provoked right-wing reactions. Aside from the left-right divide, Tamil extremists began an anti-Sinhalese terror campaign that increased the oppression of the Tamil people and strengthened the country’s divisions. In short, it all became a mess. (more…)

The Other Modern

An Architecture of Continuity:

Luis Moya Blanco’s Universidad Laboral de Gijón

In 1944, an undersecretary of Francoist Spain’s Ministry of Labour visited the city of Gijón to attend the funerals of a group of miners killed in a mine collapse. After the solemn rites took place, Turiño Carlos Pinilla met with a group of locals filled with concern for the offspring of the dead workers. All they asked of the bureaucrat was an orphanage; what they ended up with ten years later was a magnificent palace of charity, almost a city unto itself and the largest building in Spain: the Universidad Laboral de Gijón.

An example of Catholic social teaching (which upholds the essential dignity of work and the working man), the “labor university” was founded as a secondary-level institution to teach vocational and technical skills to the children of Spain’s working class. At over 2,900,000 sq. ft. of space, it is more than double the size of the great Royal Monastery and Palace of El Escorial built by Phillip II in the sixteenth century, and was accompanied by over 380 acres of farmland.

The goal was to accommodate 1,000 students (eventually doubling) from the age of 12 to 16, with residences, school facilities, industrial workshops, working farmland, athletic facilities, and sporting fields. The educational aspect and leadership of the Laboral was entrusted to the Jesuits, while the Poor Clares also had a convent on the premises, performing various household tasks and caring for the girls as their particular charism. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories