Northern Ireland

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Articles of Note: 24.II.2021

• It is almost certain that we will never know who the actual winner of the 2020 presidential election was: the methods of fraud which might have been deployed are by their very nature ephemeral. Anton is right in that the best summary of the irregularities is from the U.S.-based Swedish academic Claes Ryn: How the 2020 Election Could Have Been Stolen. Ryn’s academic work is always an insightful read so his take here is worthwhile.

• I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: the Frenchman Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is always worth reading and always brings something to the table. P.E.G. argues the pre-Trumpers, anti-Trumpers, and never-Trumpers on the American centre-right need to recognise the reasons why Trump became a political phenomenon in the first place: Why Establishment Conservatives Still Miss the Point of Trump.

• One of the best books on urbanism in the Cusackian library is Allan Jacobs’s Great Streets. The expert work with its illustrative maps, diagrams, and line drawings is now a quarter-century old and on this anniversary Theo Mackey Pollack examines What Makes a Great Street.

• A new book argues that our vision of Northern Ireland as a corrupt and gerrymandered statelet from its birth in 1921 until the imposition of direct rule in 1972 is largely a myth. The editors Patrick J Roche and Brian Barton take to the pages of the once-great Irish Times to offer A Unionist History of Northern Ireland. It’s… an interesting perspective that will doubtless provoke a debate, but colour me sceptical.

Four Reasons Rodden and Rossi are Wrong on Northern Ireland

Economics alone will not join what history has rent asunder

Academics John Rodden and John Rossi have an interesting but poorly argued piece in the normally-quite-good American Conservative “asking” the question of whether Brexit could unite Ireland at last. While ostensibly they merely posit the question, they lay out an unintended-consequences scenario for Irish political unity coming about.

If Brexit goes “wrong” then the imposition of a hard border in Ireland will drive Northern Ireland’s Protestant/Unionist community into the arms of the Republic. If there’s no hard border, then Northern Ireland and the Republic will progress down a path of natural economic integration while, Rodden and Rossi argue, “economic divergence from Britain with no hard border will show northerners that their long-term interests now lie with Dublin”.

There are some obvious problems with the Rodden/Rossi scenario.

First, the EU’s customs and economic union has already applied to Northern Ireland and the Republic for decades now and yet Northern Ireland is not economically integrated into the Republic. Of goods that leave Northern Ireland, the rest of the UK is still the strongest destination: In 2016 £10.5 billion of goods left NI for Great Britain, compared to £2.7 billion to the Republic.

True, Ulster is more vulnerable in that a bigger chunk of their exports head south of the border than the Republic’s exports head north of it. But after decades of trade barriers being torn down by the EU these two economies remain very much distinct.

Second, Rodden and Rossi fall into the trap of economic determinist thinking. The roots of Republic of Ireland/Northern Ireland divide are not economic. Ireland’s six north-easterly counties were excluded from the Irish Free State in 1921 because of the tribal fears of those counties’ Protestant/Unionist majorities of being powerless in a state that would have an overwhelming Catholic/Nationalist majority. Some of these fears were well-reasoned and considered, others were wildly irrational and bigoted.

The important thing to realise is that the divide between Nationalists and Unionists is not formed on the basis of economic arguments, though either side can deploy economic arguments in their favour. It is simply not the case that a significant chunk of Northern Ireland’s Protestant Unionist community are going to wake up some day soon and think “Well, I’ve always liked our Union Jacks, Orange marches, and devotion to the Queen but Northern Ireland might be able to achieve a 2.3% better rate of growth if we join the Republic so I’ll run up the tricolour and paint my curbside green, white, and orange”.

Third, as Rodden and Rossi confusingly point out, the coming demographic majority Catholics will achieve in Northern Ireland does not automatically equate to all-Ireland unity: An astonishingly large proportion of Northern Irish Catholics wish to maintain links to the United Kingdom. They will continue to vote for Sinn Féin and the SDLP in elections because these parties are viewed as those who vie to look after their community’s interests. But that does not necessarily mean they want to cut all ties to the UK or sign up for a 32-county unitary republic.

“Ah!,” they say. “But hard Brexit!” This is the fourth point why Rodden and Rossi are wrong. They argue that a hard Brexit would necessitate a hard border with the imposition of frontier infrastructure, tolls, taxes, etc. Rodden and Rossi claim that “[t]he only workable plan for Brexit that will prevent a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic is for the north to stay in the EU customs area despite Brexit.”

This is simply not true. By now almost everyone has conceded, including civil servants in both London and Dublin, that even in the event of a No Deal Brexit (which has pretty much been ruled out) the technology already exists to provide a fairly seamless border. The few companies whose cross-border trade would fall into the relevant categories could be checked not at the border but electronically. While anti-Brexiteers spent months arguing that this was an impossible pipe dream, the number of researchers, customs agents, civil servants, and others who point out that the technology exists and has been used in similar scenarios for years is now so voluminous as to render the argument irrelevant.

(Rodden and Rossi are also entirely incorrect in claiming that Northern Ireland has adopted “quite restrictive” laws on “abortion and gay rights”. In fact, Northern Ireland’s post-1998 democratically elected representatives have mostly decided against taking action to change existing laws on these subjects even though they have been altered or repealed in England, Wales, and Scotland.)

There are other problems with the Rodden/Rossi economic determinist case for a united Ireland. For one thing, there is an economic determinist argument against it. The Republic of Ireland is a relatively prosperous country, though obviously not without its problems. Though romanticism and patriotism have deep roots, the Republic’s taxpayer base might balk at taking on the highly subsidy-reliant Northern Irish economy, even if only with a mind to transitioning it to a more free-market scenario.

Furthermore, sources in the Irish Defence Forces are quick to express their anguish at the army’s much diminished capacity even to carry out its existing commitments with the United Nations. Northern Ireland separating from the United Kingdom and joining the Republic would almost certainly spark a revival of violence amongst a minority of the province’s loyalists. Are voters in the Republic really that keen to take on an economic and counter-terrorist burden?

All this may sound a bit Cassandra-like, especially coming from a writer with traditional “Up Dev” Fianna Fáil sympathies, but these are all factors that need to be considered and which significantly inhibit the likelihood (completely separate from the wisdom) of Irish political unity in the near future.

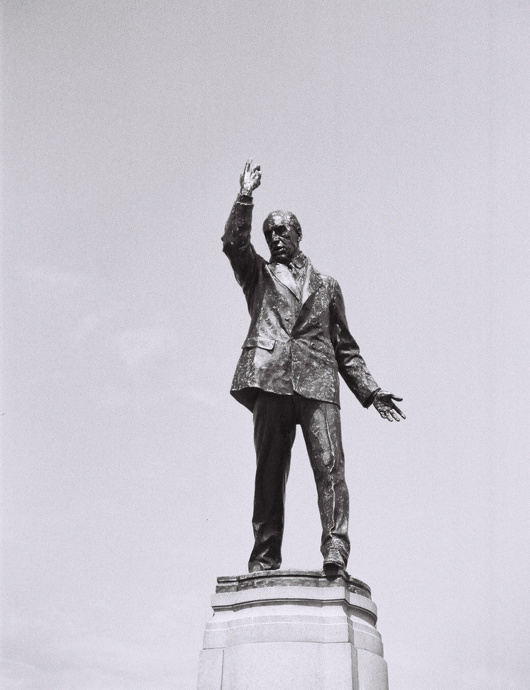

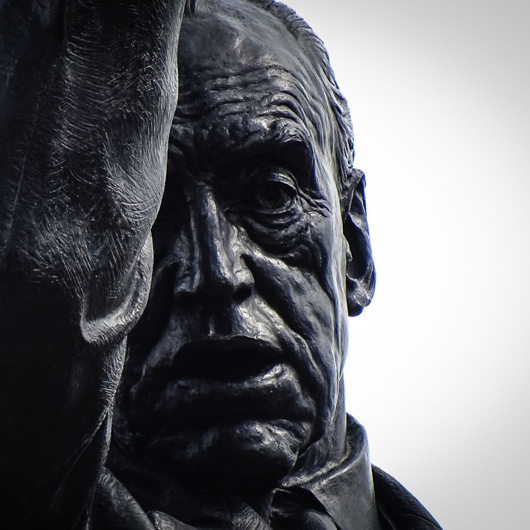

Carson at Stormont

Few statues in Ireland are as dramatic as that of Edward Carson at Stormont. The unionist leader is depicted in amidst an oratorical flourish, doubtless in one of his speeches to mass meetings condemning home rule.

In the 1910s as the rebirth of an Irish parliament looked more likely, Carson took up the cause of fighting home rule on behalf of Ireland’s large Protestant minority who feared Catholic domination. When the anti-home rulers realised the cause was losing, they retreated from Irish unionism to Ulster unionism. If home rule was to be granted, Ulster must be exempted. In the end this meant home rule was granted to a parliament covering two-thirds of the Irish province of Ulster — six counties that would henceforth be known as Northern Ireland.

“His larger than life-size statue,” one historian wrote, “erected in his own lifetime in front of the Northern Ireland parliament at Stormont, symbolizes the widely held perception that Northern Ireland is Carson’s creation.”

This is of course the great irony, given that Edward Carson was a Dublin boy through and through. While instrumental in ensuring northeastern Ireland’s exemption from an Irish parliament, Carson actually had little to do with the entity thereby created. When offered the premiership of Northern Ireland he declined it on the grounds of having no real connection with the place.

Craig, not Carson, is the true father of Northern Ireland; he imbued the new statelet with a sense of bigotry and tribal hatred that Carson lacked. The Dubliner urged Ulster’s new leaders to treat the province’s Catholics well.

“We used to say that we could not trust an Irish parliament in Dublin to do justice to the Protestant minority,” Carson said. “Let us take care that that reproach can no longer be made against your parliament, and from the outset let them see that the Catholic minority have nothing to fear from a Protestant majority.”

Alas, it became apparent to Carson that discrimination and inequality were becoming in-built within Northern Ireland’s government, from the Parliament at Stormont down to the lowest forms of local government. He confided to a Catholic friend in London that rather than being an integral part of the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland was turning into “a second-class dominion”.

After partition Carson was created a British judge and accordingly ennobled. (Disappointingly the plaque on his Dublin birthplace next to Conradh na Gaeilge refers to him by the incorrect style of ‘Lord Edward Carson’.) He settled at Clever Court near Minster-in-Thanet, Kent, and never lived in his native Ireland again.

Nonetheless he was held in awe and reverence by the Protestant Unionists of Ulster, who commissioned the striking statue by Leonard Stanford Merrifield that stands in front of Parliament Buildings, Stormont — now home to the Northern Ireland Assembly. It was unveiled by Craig, by then ennobled as Lord Craigavon, while Carson was alive and present in July 1932, joined by a crowd of 40,000 well-wishers.

Carson died in 1935 and was given the rare honour of a state funeral. HMS Broke brought his Union-Jack-draped coffin back to Ireland — albeit to Belfast — and he was interred in the Anglican Cathedral of St Anne. Northern Ireland claimed him even in his final burial: soil from each of its six counties was scattered on his coffin when laid to rest in the tomb.

Still his statue stands at Stormont, gesturing stridently as if to challenge an entire province — a province he by his own description had little to do with. Calls for it to be removed emanate occasionally from typically boring quarters and have so far been rebuffed — wisely. Carson, unlike many of those who cherished his memory, was an honourable man, and it is a pity it took so long for the Protestants of Ulster to heed the advice of their confrère from Dublin.

Flags, Northern Ireland, and the Union

Flags have been in the news of late, perhaps as a late hangover of the disruptive protests over Belfast City Council’s decision to fly the Union Jack from Belfast City Hall only on the United Kingdom’s designated flag-flying days. Ironically, this would have brought the Six Counties further in line with normal British practice, but disgruntled unionists viewed it as a diminution of “their” flag and a bit of a fracas ensued with the once-traditional death threats and intimidation returning.

The BBC raised the issue of how Scottish independence might affect the Union Jack. (Pedants only refer to the British flag as the “Union flag”, but the Flag Institute points out both terms are perfectly acceptable). Scottish independence would have no automatic effect on the flag whatsoever, but it has provoked a round of speculation over what changes, if any, should be made to the Union flag.

Then Richard Haass, the American diplomat charged with chairing the inter-party talks on unresolved issues in the Six Counties, waded into matters vexillological when he wrote to party leaders seeking their views on the possibility of a new flag for Northern Ireland. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories