Newspapers

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The life & death of The European

An idea before its time or the mad dream of a master swindler?

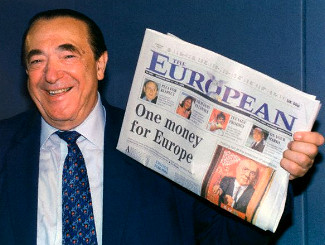

The inception of The European at the dawn of the 1990s was emblematic of the age. Triumphant scenes of joyful crowds tearing down the Berlin Wall in 1989 sparked exhilaration across the continent and the high spirits from the fall of the Iron Curtain were transformed into Euro-phoria as the ideal of a ‘United States of Europe’ now seemed a very real possibility. The media and publishing magnate Robert Maxwell vigorously supported ‘the European ideal’ and founded The European newspaper to act as a cheerleader for that ideal. Rolling from the printing presses within a year of the Wall’s fall, the newspaper had nonetheless folded by the time the Amsterdam Treaty was ratified in 1999 despite the continued growth in the size and power of European institutions. But the story of the rise and fall of Maxwell’s newspaper — the life and death of The European — is itself indicative of the strengths and weaknesses of the European project itself.

Robert Maxwell’s euro-enthusiasm might be explained by his transnational roots. “Captain Bob” (as Private Eye labeled him) was born Ján Ludvík Hoch in 1923 into a poor Jewish family in a small town in Carpathian Ruthenia — then in Czechoslovakia, now in the Ukraine — and escaped to Great Britain in 1940. He entered the British Army shortly thereafter as a private but his natural intelligence and gift for languages meant that by the war’s end he was a captain, having also been awarded the Military Cross for gallantry.

Using the many contacts he had made amongst the Allied occupation officials, Maxwell went into business as the British and American distributor for Springer Verlag, a German scientific publishing firm. In 1951, he went into publishing on his own when he purchased Pergamon Press, a textbook-printing subsidiary, from Springer Verlag, turning the company around and making handsome profits from the endeavour. A socialist, despite his business acumen, he was elected to the House of Commons in 1964 on the nomination of the Labour party, losing his seat six years later.

Through Pergamon Press, he gradually began accumulating media interests. He lost the battle to buy the News of the World to Australia’s Rupert Murdoch, who duly emerged as his arch-nemesis. By the middle of the 1980s, however, Maxwell owned the London-based Daily Mirror and Sunday Mirror, the Daily Record and the Sunday Mail (both Scottish), as well as other newspapers, a number of publishing houses, a record label, the Berlitz language schools, and half of MTV Europe, and the Oxford United Football Club.

But conventional newspapers, no matter how numerous, did not satisfy the massive ego which had become one of Maxwell’s most notorious characteristics. In June 1988, he began planning for a transnational, pan-European daily newspaper, The European, printed in colour with articles in English, French, and German. Maxwell was a keen proponent of European integration and saw the new title as a method of bridging the gap between Britain and the Continent, as well as hoping that it would act as a counterweight to the well-established American weeklies Time and Newsweek.

Maxwell brandishing issue No. 1 of The European

Maxwell’s ideal for the newspaper proved impossible to realize immediately, and when The European finally emerged on newsstands in May, 1990, it had been brought down in scope to an English-language weekly newspaper. The title emblazoned across the top — with an emblematic white dove hovering above the continent, a copy of the newspaper firmly clasped in its beak — the first copy of The European proclaimed it would bolster ‘the supporters of the integration of Europe’. Divided into three sections — the main news section, Business, and a tabloid-sized culture review named Élan — the paper made a bold use of colour long before most other broadsheets converted from black-and-white.

One million copies of the first issue were printed by Maxwell, with a guarantee to advertisers that the weekly would settle down in six months with a circulation of at least 225,000. Three months after the launch (July 1990), Maxwell claimed a circulation of 340,000 for his pet project, divided between 187,000 in Great Britain and 153,000 on the Continent. The first audited sales figure, however, came out in February 1991 with 226,000, below Maxwell’s promise to advertisers. That month, Maxwell replaced the founding editor, Ian Watson, with John Bryant, who had edited the acclaimed Sunday Correspondent during that newspaper’s brief existence.

As the sales figures continued to settle downwards, Maxwell grew less comfortable with realistic circulation estimates and he began a number of schemes aimed at driving up the numbers. That February, it was decided that ‘significantly different’ U.K. and overseas versions would be printed. In October 1991, just a few months later, Maxwell attempted to introduce an edition specific to North America, where officially 15,000 copies of the U.K. edition were sold each week. By the end of the month, however, the scheme was abandoned, and many of the hacks in The European‘s London headquarters were reduced to working a three-day week to cut corners, while some were made redundant outright.

The European aside, Maxwell’s empire was coming apart at the seams. High interest rates and a general recession were bad for business overall, but investigations had been launched into various dodgy business practices throughout Maxwell’s companies. Profits had been overstated while losses were hidden away. Money had been looted from corporate pension funds to prop up entities personally owned by Maxwell and to artificially inflate share prices. The London Metropolitan Police were even compiling a file on Maxwell’s war years, towards the aim of charging him with war crimes for killing at least one German civilian.

On November 5, 1991, Robert Maxwell disappeared from his super-yacht sailing off the Canary Islands, and his body was found floating in the Atlantic shortly afterward. Officially ruled an accidental drowning (the more imaginative claimed he was murdered), most assumed that “Captain Bob” had taken his own life rather than face the unravelling of his business empire and its supportive web of deceit. Maxwell was buried five days later on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, with Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir delivering the eulogy.

Ian Maxwell, the paper’s chief executive and son of the dead proprietor, announced to the assembled staff the true extent of his father’s crimes and their consequent impact for the newspaper, bursting into tears before making a quick exit from the newsroom. Not only were the various Maxwell operations suddenly and very seriously bankrupt, but it became apparent that Maxwell had continually fiddled with the newspaper’s circulation figures. “Rumour had it,” wrote one editor, Richard Holledge, “that copies were being burnt by that year’s particular brand of rioting French” outside the continental print site in Beauvais, and “[t]heir charred numbers were added enthusiastically to the figures”. “A better rumour,” bearing in mind Maxwell’s end, Holledge continued, “was that copies were shipped across the Channel, lost overboard and also added to the circulation”.

Bereft of its chief architect and founder, it was widely thought that The European would have to call it a day and cease operations. The remaining staff held a raucous Christmas party, presuming it would be the last undertaking of ‘Europe’s national newspaper’. But the party was far from over. Deputy editor Charles Garside, an old hand with experience in many a Fleet Street newsroom, bought the title and organised the staff, who worked without pay over the Christmas holiday in order to keep The European alive long enough until a suitable owner could be found. On one of the first weekends of 1992, Garside flew to Monte Carlo, returning the following Monday with new proprietors for The European: the famously reclusive Barclay brothers.

Identical twins, David and Frederick Barclay first made their money with a hotel they expanded into a chain and were not previously involved in the media. Under the Barclay regime and with Garside at the editorial helm, the aim was not so much to advance The European, as it was under the circulation-mad Maxwell, but to stabilise the title. With growth in sales in France, Germany, and Spain, the newspaper brought back Élan, its third section which had been suspended while the paper was losing £1 million a month. By the end of the year, the circulation appeared stable at 200,000.

As 1993 dragged on, however, the circulation dropped by at least 20,000. By August, fourteen members of staff were sacked and a plan was made to move The European into a more upmarket niche. A month later, Garside resigned and was replaced by the long-time managing editor Herbert Pearson. Pearson was immediately undermined when the Barclays’ managing director Greg MacLeod secretly prepared a magazine version of The European with a greater emphasis on features and analysis. The Barclay brothers, known for being hands-off proprietors, expressed little interest in the MacLeod project. MacLeod made his exit and Garside promptly returned as editor in June of 1994.

All continued as per usual until October 1996 when the Barclays appointed the former Sunday Times editor Andrew Neil as editor-in-chief of the Barclays’ three newspapers: The European and the two Scottish titles, The Scotsman and Scotland on Sunday, which they had bought a year before. Soon after, and surprisingly to the staff, Garside quit as European editor and Neil took over that responsibility too, with Herbert Pearson acting as the day-to-day head honcho. Andrew Neil brought new ideas to reinvigorate the paper but the perennial plan to turn upmarket finally materialized in 1997. The European was transformed into a high-end tabloid-sized colour magazine from June 1997 before it emerged in its final magazine form in March 1998.

But the Barclays were at the end of their tether. The European had lost £50 million since they took it over in 1992, and through the many trials and transformations its circulation failed to stabilise and continued its decline. By the middle of 1998, the Barclays threw in the towel and put The European, with Gerald Malone now at the editorial helm, up for sale. In September, it was announced that, unless a buyer was found, the paper would be wound down over the next ninety days. While there were hopes for an eleventh-hour savior in the form of Time Warner, and then Bloomberg, neither conglomerate made an offer. The final number of The European came out on December 14, 1998.

What then was the cause of The European‘s downfall? While it may seem strange that ‘Europe’s national newspaper’ faltered during the decade that witnessed the greatest leaps in European integration, the title was beset by such a multitude of problems from the very start that one might very well ask the question how it survived so long.

While undoubtedly the driving force behind The European, Robert Maxwell, with his erratic disposition, was a problem in and of himself. The unreliability of the paper’s circulation figures, actively fudged by ‘Captain Bob’, made advertisers think twice before investing part of their marketing budget. Maxwell’s problematic nature culminated in the massive financial scandal that rocked his empire, finalized by his mysterious death at sea. That the newspaper survived the death of its animating spirit so soon after its foundation is testament to the people who were determined to keep The European alive.

The commercial end of the newspaper’s operation was always a source of woe. Maxwell had been obsessed with newsstand circulation and so The European was one of the few newspapers that was actually more expensive to subscribe to than to buy from a newsagent — a factor which was unhelpful in building a loyal readership.

Starting a newspaper aimed at the middle-market at a time when that market is abandoning the printed media was doubtless an insolvable conundrum. The most obvious solution was to reorient the newspaper upmarket and find a suitable niche, but that too was already well taken care of by the Financial Times, the Economist, and the Wall Street Journal.

Distribution, meanwhile, was “an impenetrable mystery” according to Gerald Malone, the paper’s final editor. “I could never buy it in [the London Borough of] Wandsworth, but without fail found a copy in the village shop in Earlston, a tiny community in the Scottish Borders.”

Malone also claimed The European‘s staff was somewhat inconsistent in ardour. Mixed amongst the “hardworking young talent” and the “corps of professionals who brought the paper out through thick and thin” were “prima donnas” and “opinionated misfits past their sell-by date”. “In fact,” Malone wrote after the newspaper’s demise, “they were Fleet Street’s finest freeloaders: old-style fat-cats paid prodigious sums, in one case £75,000 for a three-day week”.

“One senior editor, who carped when I complained that the newsroom often resembled the aft deck of the Mary Celeste, resigned minutes before I could sack him, resenting my outrageous demand that he spend a bit more time in the office and forego long, boozy lunches fuelled with with Bulgarian wine.”

These practical problems aside, The European suffered a debilitating schizophrenia from birth. It claimed to be a European newspaper published in English but it was viewed more as a British newspaper reporting on European affairs. Maxwell’s stated aim (“Barking mad,” according to Malone) was to produce a newspaper for “the housewife in Toulouse”. But the Tolosanian housewife was already well catered for by the media of her own country, printed in her own language.

With institutional schizophrenia, a host of distribution problems, a staff of “freeloading prima donnas”, and the disappearance of its founder into the murky depths of the sea, it is indeed surprising that The European managed a good eight years in print. But besides all these there remained a never-solved existential dilemma at the heart of The European — “Europe’s national newspaper” — that it was impossible to be the national newspaper of a nation that doesn’t exist.

How a newspaper should look

The Sunday edition of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung has always been a handsome newspaper. I admired its appearance so much that it provided much of the inspiration for the look of the Mitre during my editorship of that august publication. The weekday FAZ was famously reactionary in forbidding the appearance of photographs or any colour on the front page, so the Sonntagszeitung was viewed as an opportunity to be a bit more colourful and a little more free, but still within a solid traditional design.

It saddened me to learn that the Monday-through-Thursday FAZ has given in to the Spirit of the Age and now allows not only colour on its front page but photographs there as well. It now looks like a fairly conventional German newspaper, rather than the king of German dailies.

I will miss the old black-and-white FAZ because for me it brings back memories of visits to Dr. Timmerman‘s flat in St Andrews. Sofie and I used to go over to the good professor’s place for German pancakes on Shrove Tuesday (or to listen to his giant old radio, or to simply enjoy good conversation with good wine) and he had a massive pile of Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitungs which I believe he only discarded at the end of the month.

Because the Frankfurter Allgemeine‘s front page is now a little less boring, the world in general is now a little less interesting.

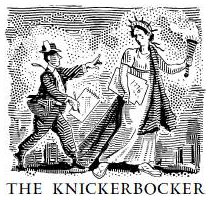

Herald-Tribune Drops Iconic ‘Dingbat’

Famous Emblem from 1886 is Dropped in Move to ‘Modernize’

The International Herald Tribune has unceremoniously dumped its unique 142-year-old nameplate logo, affectionately known as the “dingbat”. The graphic made its first appearance in the New York Tribune on April 10, 1866. The Tribune later merged with the New York Herald to become the New York Herald Tribune. The Herald had previously founded a separate European edition based in Paris. While the New York newspaper died in 1967, its weekly New York supplement survives as New York magazine and the Paris edition became the International Herald Tribune, jointly owned by the Whitney family and the New York Times. The Whitneys sold their stake to the Washington Post, which in turn ran the paper in alliance with the Times until 2002, when the New York Times Company became the sole proprietor of the IHT.

The International Herald Tribune has unceremoniously dumped its unique 142-year-old nameplate logo, affectionately known as the “dingbat”. The graphic made its first appearance in the New York Tribune on April 10, 1866. The Tribune later merged with the New York Herald to become the New York Herald Tribune. The Herald had previously founded a separate European edition based in Paris. While the New York newspaper died in 1967, its weekly New York supplement survives as New York magazine and the Paris edition became the International Herald Tribune, jointly owned by the Whitney family and the New York Times. The Whitneys sold their stake to the Washington Post, which in turn ran the paper in alliance with the Times until 2002, when the New York Times Company became the sole proprietor of the IHT.

The Paris-based newspaper’s executive editor Michael Oreskes said he hoped that dropping the dingbat would make the front page “cleaner, more modern, more streamlined”. Vanessa Whittall, the Herald Tribune‘s communications manager, meanwhile said “by removing the traditional ‘dingbat’ graphic between Herald and Tribune we have created a more contemporary and concise presentation that is consistent with our digital platforms.”

The New York Times Company has been beset with problems in recent years, with both profits and circulation falling; one Manhattan outlet reported seeing an 80% drop in sales of the Sunday New York Times. Shareholders have claimed that the general downturn for newspapers has only been exacerbated by Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, Jr.’s poor management. The decline of the Times has been mirrored in the IHT, which it now markets as its international edition.

Under the Times‘s control, the IHT has been seen to become more of a newspaper for Americans abroad than an American newspaper for an international audience. The blogger of “Think!: The blog for readers of the International Herald Tribune” questioned the prominence the paper devotes to American stories: “How a piece about baseball in the Netherlands (where I lived for three years) got more play directly next to an article about a cyclone in Burma that has killed around 100,000 people is a little hard to follow.”

Above, the traditional nameplate. Below, the ‘modern, streamlined’ nameplate.

The decision to remove the dingbat certainly has its critics. Juan Antonio Giner, the founder of a media consulting group and blogger at Innovationsinnewspapers said the move was “not a big revolution or a smart strategic decision for a dying newspaper”. Mr. Giner compared the management’s decision to “play with such a traditional, magnificent, beautiful, well-done logo” as “like moving the chairs on a sinking Titanic”.

The original dingbat, above, with the most recent incarnation below.

In “The Paper: The Life and Death of The New York Herald Tribune”, the definitive history of the deceased journal, Richard Kluger described the dingbat:

“in the middle of the crudely drawn tableau is a clock reading twelve minutes past six – no one knows why (conceivably it was the moment of Horace Greeley’s birth); to the left, Father Time sits in brooding contemplation of antiquity, represented by the ruin of a Greek temple, a man and his ox plowing, a caravan of six camels passing before two pyramids, and an hourglass; to the right, a sort of Americanized Joan of Arc, arms outstretched beneath a backwards-billowing Old Glory, welcomes modernity in the form of a chugging railroad train, factories with smoking chimneys, an updated plow, and an industrial cogwheel (over which the incautious heroine is about to trip); atop the clock, ready to take off into the boundless American future, is an eagle – all for no extra cost.”

“It was a baroque snapshot of time arrested,” Mr. Kluger continued, “an allegorical hieroglyph of the newspaper’s function to render history on the run”.

The deputy managing editor Robert Marino said of the dingbat, “I’m kind of sorry to see it go, but that’s progress.” Many of the Herald Tribune‘s readers will remain unconvinced.

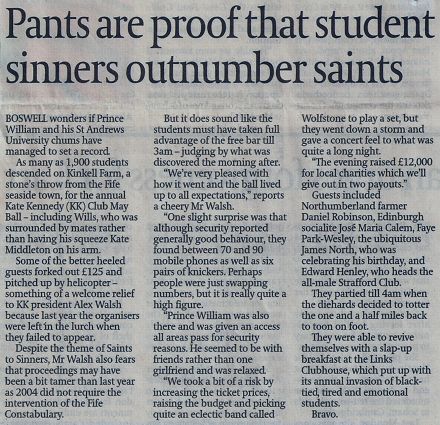

The Auld Scotsman

ONE THING WE greatly enjoyed about the Scotsman in its pre-tabloid days was that they often deemed St Andrews social events worthy of coverage in their august pages. It was a source of pride to see ‘the national newspaper’, a respectable broadsheet, covering events at the oldest university in the land (which we are proud to call our own). Naturally, once the conversion to tabloid size was complete, we were rarely heard of again, which was a little saddening. The Scotsman is not what it used to be —a beautiful, well-designed, informative respectable newspaper— but it still manages to print some thoroughly worthwhile articles which is more than can be said of any other Scottish daily. (One need only point out two articles by Prof. Haldane, c.f. here and here, recently posted on this site).

“…when the diehards decided to totter the one and a half miles back to toon on foot.” Sounds familiar.

Admittedly, most of the events covered were organised by the Kate Kennedy Club, which seems to take pride in the sheer vulgarity and tastelessness with which they advertise many of their events. (This is only slightly mitigated by their superb running of the annual Kate Kennedy Procession). Still, we enjoyed the Scotsman‘s coverage and wish it had continued. I only bought the Scotsman on occasion after the switch, but often gave the Common Room’s copy a browse when I lived in St. Salvator’s. (Its Sunday edition, Scotland on Sunday is worth buying for Gerald Warner alone).

Here are a few bits and pieces clipped from the Scotsman for your perusal:

‘Undampened spirits take the party indoors‘ / Lumsden Club garden party moved indoors on account of the rain. (I didn’t go).

‘High jinks and low cuts at Kate Kennedy’s‘ / This covered the Kate Kennedy Procession dinner which takes place at the Old Course Hotel on the evening following the procession. This particular year I was in attendance myself and recall commiserating with Michelle Romero, that charming daughter of Venezuela, about the troubled state of her native land. I was their with our favorite Dane, Sofie von Hauch, and my flatmate, a member of the KK who wishes to remain unnamed on this site. Will Lyons couldn’t make the dinner himself, so he sent ‘K‘ up instead, accompanied by ‘society photographer Z‘ whom I ran into while we were on our way out.

‘Maltesers set ball rolling for charity‘ / The 2004 Knights of Malta Ball, not covered by this website because it did not exist at the time. It was a good time, especially so because I had three friends over from the States. Yalie Adam Brenner was doing his semester abroad at St Andrews at the time, and fellow Old Thorntonian Clara de Soto popped over from Boston College for the weekend with her good friend Katie Cordtz of Atlanta. The four of us together with Michelle Romero and the aforementioned unnamed flatmate of mine piled into a cab and made the hour’s journey to Edinburgh for the soirée. Poor Adam, though. Towards the latter part of the evening Archie Crichton-Stuart, an exceptionally amusing Edinburgh student, and his friend Ramsay forced Adam to consume the significant remnants of a bottle of house red. It all went down swimmingly, but came back up on the cab ride back to Fife. Freddy McNair, who was recently nearly killed by an incompetent gurkha on a training ground, sat at the table next to ours, I recall. (Also, in the lower right-hand corner of the clipping you can spy the face of our good friend Ricky Demarco peering out from an unrelated article).

Previously: Another Broadsheet Bites the Dust

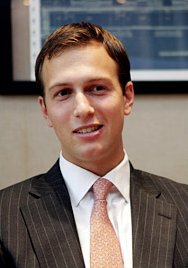

Can Kid Save This Sinking Ship?

25-Year-Old Buys the Salmon Siren of the Upper East Side

AN NYU LAW  student of just twenty-five years of age has purchased the majority stake in the New York Observer. Jared Kushner (right), son of the currently jailed big-time donor to the New Jersey Democrats Charles Kushner, bought the biggest-piece-of-the-pie off of publisher Arthur Carter, who founded the insouciant weekly printed on salmon-tinted paper back in 1988. No official word on how much money changed hands during the deal, though the Times cites “one person familiar with details of the sale” claiming the amount was nearly $10 million. Carter will maintain a significant say in the paper’s operations, and there are no plans to make any changes to the masthead as of the moment. Earlier in the year Robert de Niro was in talks to buy the Observer through his Tribeca Film Festival operation, but the negotiations fell through.

student of just twenty-five years of age has purchased the majority stake in the New York Observer. Jared Kushner (right), son of the currently jailed big-time donor to the New Jersey Democrats Charles Kushner, bought the biggest-piece-of-the-pie off of publisher Arthur Carter, who founded the insouciant weekly printed on salmon-tinted paper back in 1988. No official word on how much money changed hands during the deal, though the Times cites “one person familiar with details of the sale” claiming the amount was nearly $10 million. Carter will maintain a significant say in the paper’s operations, and there are no plans to make any changes to the masthead as of the moment. Earlier in the year Robert de Niro was in talks to buy the Observer through his Tribeca Film Festival operation, but the negotiations fell through.

The Observer, with a small-but-influential circulation of 55,000, has undergone a miniature transformation recently with the hopes of turning around the current losses of about $2 million a year. The most noticeable of these changes came in May when the paper trimmed over an inch in width, moving from six front-page columns to five and giving it a taller, more narrow appearance. While the thinner size saves on rising newsprint costs it also means diminished space for advertising, and the newspaper lost its easy, leisurely feel, also moving from two sections to one. The Observer has also increased the volume of its internet operations on Observer.com, some might say at the expense of the quality of the printed edition. The new owner, however, will take a back seat in the content of the newspaper while concentrating on improving the bottom line, citing the Observer‘s strong brand despite its current financial woes.

Kushner’s father, a well-known New Jersey real estate developer, was sentenced to a jail term last year after being found guilty of tax evasion, and is well-known for a number of other stunts which do not bear repeating on, er, family-friendly sites such as this. The younger Kushner himself has given over $100,000 to various (Democratic) political outfits since 1992, when he was a mere eleven years of age.

I used to read the Observer often (though not regularly) because it had the most style of all the New York newspapers. While its flighty spirit meant it lacked a certain depth, it still had zing and usually at least a handful of interesting articles each week. The quality of the content began slipping, however, and when I came home to New York I bought one copy while waiting for the train in Grand Central, was completely dissatisfied like the new size and feel, and decided to give it up. I will always have a certain fondness for the Observer though; in the age when Gannett-style corporate monotony is king, it has managed to maintain a certain classic swankiness (epitomised in its reporter-and-skyline emblem) and for that we can be grateful.

The Sad State of the Modern Newspaper

…and the heroism of an Anglo-Hungarian countess.

IT IS ONE OF THE more saddening facts of life that British newspapers have suffered an inexorable decline in the past few years. The great Times of London – once the most respected newspaper in the world – has been reduced to a boring mid-brow tabloid, the once-solid Scotsman idiotified and, again, tabloided, and of course the Daily Telegraph, which has gone from staunchly conservative (as in worldview) to merely Conservative (as in the tribe of Britons who prefer blue to red).

The Telegraph, like the Conservative party itself, doesn’t seem to know what it’s there for. It has at least remained a broadsheet; going tabloid would be a disaster and would probably be considered the last straw for all the die-hards for whom loyalty to one’s newspaper is a point of pride. And, to its credit, it finally seems to have realised the damage done by constant front-page photos of “Posh” and “Becks” and other “celebrity” partisans of the Anti-Culture, for they seem fewer and far between these days (as compared to a year or two ago, when they were frequent). The Telegraph‘s base are old folk who want a quality newspaper. They are loyal to the Tele and, despite its decline, would be too embarrassed to jump ship to the Guardian, which is written better but which nonetheless expones a nefarious ideology.

As for myself, the last straw came one morning in the Common Room of St. Salvator’s Hall when, flipping through the Telegraph, I reached the page which normally displays the Court Circular but found it missing, replaced by a curt statement advising that should I desire information about the activities of the Royal Family I should direct myself to http://www.royal.gov.uk. Outrageous! As it happens, this is not a permanent loss but rather an occasional one, as the editors at the Telegraph seem to decide whether or not to print the Court Circular each day on a whim. Fair enough, but I came to the realisation that the producers of the Telegraph are not aiming at me – the reasonably educated young man who seeks in his daily read a newspaper that is well-written, right-thinking, and properly presented – and so I have ceased to be a Telegraph regular.

What to read then? We have already dismissed the Times, the Scotsman, and the Guardian. The Daily Mail is always readable but arguably aimed at a different demographic; the Daily Mirror, bonkers; the Sun, no thank you!; the Financial Times is too boring, though the Weekend edition is actually worth buying most of the time; the Independent has a good layout for a tabloid, but is rather of a Lib-Dem persuasion; the Glasgow Herald is just rather dull and has only recently repented of its long-held anti-Catholicism. Not wanting to support the nefarious New York Times, enemy of Western civilization and the last word in liberal elitism, its wholly-owned subsidiary the International Herald-Tribune is ruled out. Which pretty much rules out every English language daily newspaper available in St Andrews.

So, abandonné par ma langue, I have outsourced my daily read to the Continent (of all places!) and am now a partisan of Le Figaro. While by no means fluent in the language, I can comprehend written French with greater ability than I speak it. And while I still prefer the feel of a broadsheet, the Berliner size of Le Figaro has its advantages, being very easy to read in the confined space of my regular chair in the corner of the little coffee shop down the street. More importantly, I find it much more engaging mentally, which I put down to the fact that (not being a native or fluent French speaker) I am forced to read every word. Reading the Telegraph one unthinkingly only actually reads every third or so word; articles of particular interest excepted, naturally. The day’s Figaro usually arrives in the middle of the day or the afternoon, but I buy my paper in the morning so actually I’m usually reading the previous day’s Figaro. I don’t mind, it suits my current routine. (Mornings are for reading the newspaper in a coffee shop, afternoons are for reading books with a slow pint in the pub.)

So, abandonné par ma langue, I have outsourced my daily read to the Continent (of all places!) and am now a partisan of Le Figaro. While by no means fluent in the language, I can comprehend written French with greater ability than I speak it. And while I still prefer the feel of a broadsheet, the Berliner size of Le Figaro has its advantages, being very easy to read in the confined space of my regular chair in the corner of the little coffee shop down the street. More importantly, I find it much more engaging mentally, which I put down to the fact that (not being a native or fluent French speaker) I am forced to read every word. Reading the Telegraph one unthinkingly only actually reads every third or so word; articles of particular interest excepted, naturally. The day’s Figaro usually arrives in the middle of the day or the afternoon, but I buy my paper in the morning so actually I’m usually reading the previous day’s Figaro. I don’t mind, it suits my current routine. (Mornings are for reading the newspaper in a coffee shop, afternoons are for reading books with a slow pint in the pub.)

The chief deficit of reading a French newspaper is that naturally the news is oriented towards France, and thus I don’t get the usual transatlantic focus of the British papers (which can be an advantage as well as a deficit, I’ll concede). Nonetheless, it does happen to have articles of interest to any trad.

A few weeks ago, Le Figaro reported on the restitution of Romanian castles to their original, pre-Communist owners (‘L’impossible restitution des biens en Roumanie’, Le Figaro, 21 April 2006). The New York Sun rather amusingly and provincially headlined the story “Westchester Man To Take Possesion of Dracula’s Castle” — the New York Post characteristically used the headline “VLAD TIDINGS“. (FTD also reported on the restitution of Bran). When I wrote my previous post on the subject I was under the impression that Bran was one of the castles which would be restituted and then purchased back by the Romanian government, but most sources imply that this is not the case and Dominic von Habsburg (of North Salem, New York) will actually take possesion of the castle, I’m glad to hear.

This morning, then, I read in Le Figaro of the controversy surrounding a red star which remains on a Soviet war memorial in a small town in Hungary, a country which has banned all Communist and Nazi emblems (‘Hongrie: Le pasteur, la comtesse et l’étoile rouge’, Le Figaro, 6 May 2006). The local Protestant minister has been fighting to replace the red star, and has found an ally in Countess Jeanne-Marie Wenckheim-Dickens. The Countess, aged 70 and a descendant of Charles Dickens, returned to Hungary a few years ago after her husband died. The family had fled the country in 1944 just escaping the conquering Red Army. “I return home,” the Countess says (‘with a delicious British accent’, Le Figaro reports), “and what do I find? My castle transformed into an elementary school with, right in front of the gate, a red star! To me, this star is the Antichrist.”

The Countess funded the restoration of her former castle, now a school, and obtained permission from the town to live in the old presbytery, an ancillary building of the old castle. But when, in 2004, she proposed to mark the accession of Hungary to the European Union by replacing the red star on the monument with a European flag, the ex-Communists in the town hall told her she “should not be afraid of the red star, but of the Cross!” With fighting spirit, “I placed a large cross on my entryway,” the Countess says, “then I painted it gold so that the Mayor, whose window is opposite, can see it all the better.”

“Crosses? She can build a hundred of them!” the Mayor said. “It doesn’t disturb me!” But in return the Mayor had a house on what was the domain of the Wenckheim family renovated for the use of unemployed local gypsies. “It was clearly to annoy me,” the Countess said. “They thought the gypsies were going to make the area around the nearby church, built by my grandfather, filthy. But not at all! They respect the place, and I, I love their music very much.” The Countess also gives weekly catechism lessons to the local gypsies. In her window, she displays a letter to the people of the town inviting them to vote for the conservative Fidesz party. “In December,” the Countess continues, “before Christmas, I add little angels and holy pictures; they don’t like that much across the way, since they’re aimed at the town hall. Because I, too, have a star: but is the star of the Shepherd”.

Grande Journalerie

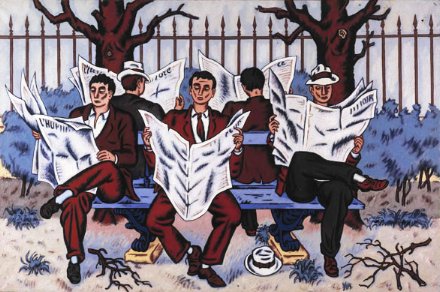

Jean Hélion, Grande Journalerie

Oil on canvas, 51″ x 76″

Robert Miller Gallery, New York

A Bit of Sun

My ownly major aesthetic gripe against the Sun is the layout of the front page of their Friday second section, currently titled ‘Arts+’. (The ‘plus’ presumably refers to the inclusion of the Sports pages towards the end). Below at left is Section II as it appeared in the September 2-4 edition. The sans-serif font is just a tad too Gannett for a publication as esteemed as the Sun. To the right and below it I have placed two proposals for a reform of the Section II front page, both of which, I believe, are much more in keeping with the general aesthetic and demeanor of the rest of the New York Sun.

Which Way Forward for the Sun?

Marty Browne, a loyal reader from Queens, has brought to my attention that a hooplah has taken place in a few media outlets recently concerning our beloved New York Sun. Essentially, two memos written by Robert Messenger, deputy managing editor of the Sun, were somehow leaked to Gawker, Gotham’s flitty rumor mill, and posted on May 11, 2005.

The two memos deal with the state of the Sun at the moment and highlights some concerns over its long-term future, suggesting something of a ‘back to basics’ course for the three-year old conservative broadsheet. Our friend Mr. Browne was concerned enough to write a letter to the editor cautioning against changing our beloved Sun, bar adding a few more voices from the old right (advice which should be heeded). But having read the memo, I think it offers a frank analysis of the paper today and productive suggestions for the direction it should go in.

The two memos deal with the state of the Sun at the moment and highlights some concerns over its long-term future, suggesting something of a ‘back to basics’ course for the three-year old conservative broadsheet. Our friend Mr. Browne was concerned enough to write a letter to the editor cautioning against changing our beloved Sun, bar adding a few more voices from the old right (advice which should be heeded). But having read the memo, I think it offers a frank analysis of the paper today and productive suggestions for the direction it should go in.

Essentially, what the Sun has to do is decide what it will be. It would be excellent if New York could have a general interest conservative broadsheet newspaper. However, given the overwhelmingly liberal market, I doubt the city’s ability to support such an endeavour; a luxury we sadly cannot afford.

In the mad media market of Manhattan, the most reliable option for the Sun is not as a general interest paper, a more financially-precarious model, but instead to find a niche in which to solidly rest. The weekly New York Observer, only born in the nineties, has a niche which gives it a fairly firm foundation provided it continues to serve it well, and the Sun should take note of that.

Thus the niche market is the way to go. What niche though? In my opinion, the New York Sun should be three things: 1) Conservative, 2) High-brow, 3) Metropolitan.

1) The Conservative Newspaper: The right-minded mustn’t just give up and concede New York as legitimately 100% liberal. This simply would not reflect reality, and the Sun must continue to provide a conservative voice on a higher scale than the populist New York Post.

2) The High-Brow Newspaper: Arts & Letters is already the most flourishing section and long may it continue. James Gardner on great on Architecture and I am absolutely loyal to the architectural historian Francis Morrone’s ‘Abroad in New York’ column every Monday. The Editorial and Opinion sections provide good sound argument and discussion, but could do with expansion.

3) The Metropolitan Newspaper: Of course it must continue to be an intrinsically New York paper. Coverage of the civic, political, and social sides of the city are essentially. This department has been pretty solid and consistent, and should only be augmented.

Should the New York Sun aim to be the conservative, high-brow, metropolitan newspaper, I believe it will be a winning formula, and set the newspaper well along on path towards becoming a great New York institution, if it isn’t one already.

(Continue reading for my thoughts on a few of Mr. Messenger’s points.)

Taki on the Sun

In this week’s Spectator, the ‘poor little Greek boy’ Taki informs us of a feud between the Dorothy Parker Society and the F. Scott Fitzgerald Society. Apparently the DPS invited the FSFS to a big to-do at the Algonquin and the FSFS didn’t even respond. “I get all this info from my favourite Big Bagel paper, the Sun, or the Sharon, as I call it, because of the line it follows where Israel is concerned.” I love the Sun, and I’m very glad Taki has discovered our favorite New York daily. He continues:

Benchley, like Parker, was a founding member of the Algonquin round table, and was known to have spilled more booze than F. Scott ever downed. Unlike the latter, he could hold it. Emerging once from the Waldorf Astoria, he commanded a doorman to get him a taxi. ‘How dare you, Sir,’ came the answer. ‘I am a United States admiral.’ ‘Well, in that case,’ said the well-oiled Benchley, ‘get me a battleship.’

Moving along…

I have not read his book, which is coming out sometime next year, but press reports have it that he was delighted by what he discovered. His accounts apparently have no condescending references to the kitsch or to materialism, which so many of us Europeans refer to every time we write about or mention America. That’s because he went to places like Cooperstown, New York, where the baseball hall of fame museum is located, or to Pennsylvania, among the Amish. (Not much materialism among that lot, that’s for sure.) And a poignant moment, when he is accosted by a Michigan policeman and told to stop loitering and to keep moving — BHL is relieving himself in a field — and he informs the cop that he’s a Frenchman and that he’s following Tocqueville’s footsteps, which results in a pleasant conversation.

Yes, Americans are nice people who want to be nice and do not understand why the Europeans hate them so. Our own Paul Johnson explained it all some weeks ago when he said that, if he were younger, he’d move to the land of plenty. Sure, manners are not an American strong point, nor is its taste for music and movies. But the natives are friendly, vulgar and nice, which is a lot more than I can say for some of us from the old continent.

I seem to have misplaced or thrown out (shudder!) the Speccie with Paul Johnson’s salient words urging and young people with talent in Britain to move to America, but if I do find it, I shall post his words of hope.

Dingbat Through the Ages

Newsdesigner.com has an interesting post enlightening us to the history of the ‘dingbat’, the vignette which can be found atop the International Herald Tribune.

The design first originated in the nameplate (also called, varyingly, the ‘masthead’, ‘banner’, or ‘flag’) of the New-York Tribune. The Tribune became the New York Herald Tribune, which my Aunt Naomi informs me was a very good newspaper while it lasted. The NYHT died in 1966, being merged into the ill-fated New York World Journal Tribune (aka the Widget) which only produced a few numbers before labor troubles killed it too.

The Herald Tribune, however, has two remnants which still exist today: the Paris edition (now the IHT) which continued under the auspices of the New York Times and the Washington Post, now solely owned by the Times; and New York magazine, which started out as a weekly supplement to the Herald Tribune.

Huzzah for the Sun

What?!? You still don’t read the New York Sun? Well you’re a fool then. I used to think the Daily Telegraph was the greatest newspaper in the English-speaking world, but now I think it’s got to be the New York Sun. It’s the quality hometown newspaper for the greatest town that ever was.

Almost like comparing the City of New York to the New York Times, the Sun is more colorful, less pretentious, loves America, and is a million times more interesting. The only way the Times is more like New York than the Sun is that the Times is so big you can never get through all of it at once.

Almost like comparing the City of New York to the New York Times, the Sun is more colorful, less pretentious, loves America, and is a million times more interesting. The only way the Times is more like New York than the Sun is that the Times is so big you can never get through all of it at once.

In yesterday’s Sun there was a fascinating profile of ‘the Rev’ (photo below), the men’s room attendant in the 21 Club. It was absolutely fascinating to find out about a gem of a man such as he. Reading the Times is arduous and depressing, whilst reading the Sun is informative and pleasing.

Purchasing an online subscription to the Sun was the wisest investment I think I’ve ever made. And economical as well at a mere $16.50 per quarter (with free 4-week trial period), allowing me to cancel for the quarter of the year I can actually buy the paper edition. Most satisfying.

Another Broadsheet Bites the Dust

The Scotsman has given in to the current Fleet Street mania and become a tabloid. The newspaper had experimented with the tabloid size for its Saturday edition and then just a few days ago converted the weekday editions as well.

For my fellow Americans in the audience, a little explanation. Going tab is all the rage amongst respectable newspapers in Britain over the past year. The ancient Times of London comes in both broadsheet and tabloid format. The Independent was the first broadsheet to publish both a broadsheet and tabloid edition, and then decided to become a permanent tabloid. The Guardian, to my knowledge, has kept out of the tabloid fray, and the venerable Daily Telegraph remains commited to broadsheetism.

The benefits of publishing in tabloid size are that the newspaper is easier to handle and read. Financially, however, it means page size, and thus potential advertising space, is reduced by half.

I am not a fan of this tabloid revolution. I fantasize periodically about the Mitre being published in broadsheet format instead of A4. Perhaps my anti-tabloidism is culturally ingrained. After all, we Anglophones are used to the formula of broadsheet = trustworthy. This formula is not true, for example, in France, where the two main respectable newspapers, le Figaro and le Monde, are printed in a format slightly smaller than the standard US/UK tabloid.

Nonetheless, one of the aspects of broadsheets that I enjoy is that they aren’t easy to read on subways and whatnot. It’s best to sit down in a comfortable chair in a well-lit location and peruse the goings-on and thoughts of New York, the nation, and the world in the New York Sun than to get tiny bits of news in a “convenient” format.

Pensées des Journaux

TODAY I WAS wondering how many daily newspapers there actually are in New York. I thought I knew all the English ones, the Spanish ones, and that there were a few Chinese ones as well. So my vague idea was somewhere around seven or eight.

After turning to the Encyclopedia of New York and the internet, by my count there are thirty-five dailies in New York, printed in nine different languages!

Eighteen English, five Chinese, three Korean, three Spanish, two Greek, one Italian, one Polish, one Russian, and one Ukrainian. That’s a very large number of newspapers for one city to sustain, though it ought to be remembered many of the language papers are purchased widely in other areas. Still, I wonder if Tokyo, Mexico, Seoul, Sao Paolo, Mumbai, and the other megacities out there have as many daily newspapers.

The eighteen English dailies by founding date are: (more…)

Quoth the Sun: ‘It Shines For All’

Have I ever mentioned how much I enjoy the New York Sun? It’s wonderful to come home to the Great Metropolis and read a broadsheet that doesn’t come off as sanctimonious and elitist (ahem, überliberal New York Times). I’m beginning to think the Sun may even be better than the Daily Telegraph. After all, I don’t believe I’ve ever seen any articles about ‘Posh and Becks’ in the New York Sun.

Like the Mitre, I dare say, it has a layout that is both contemporary and traditional. (There’s also a definite 1920’s aura to the Sun). And most unlike the Times, it is succint, taking up only twenty-two pages to the Times‘s one-hundred and sixteen. Mind you, I’d be the last to complain if it expanded in size. In fact, it could do to grow to perhaps thirty-something pages. But as our old headmaster used to say, to write, you have to be pompous. You have to believe others ought to be reading what you write. And at one-hundred-sixteen pages daily that means the New York Times is one of the most pompous newspapers around. No shocker there.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Amsterdam November 26, 2024

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories