New York

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Paris Arts & American Arms

Maj. T. L. Johnson’s Cartographic Mural on Governors Island

One of the best aspects of the inter-war construction of Governors Island is that the refinement of McKim Mead & White’s architecture is matched inside by a series of interior murals painted under the auspices of the WPA. These murals often veered towards the refreshingly jocular, as can be seen in the War of 1812 mural in Pershing Hall (a corner of which is captured here by photographer Andrew Moore). The mural by Major Tom Loftin Johnson (educated at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris) depicted here, however, is a map of the area under the purview of the Second Corps, U.S. Army headquartered at Governors Island; namely the states of New York, New Jersey, and Delaware, and the then-territory of Puerto Rico.

A new bookplate for the NYG&B

Fr. Guy Selvester reports on his resurrected Shouts in the Piazza blog that the great Marco Foppoli has designed a new bookplate for the New York Genealogical & Biographical Society. Mr. Foppoli is the most highly-regarded heraldic artist of our day, and the influence of the style of his mentor, the late Archbishop Bruno Heim, is apparent in his work.

Eric Seddon on Washington Irving

Alongside Miklos Banffy, Washington Irving is probably my favourite author. I have two sets of his complete works, and will obtain at least a third — my favourite printing of the complete Irving, in an excellent handy size — when I can find it for the right price. It is curious, but by no means suprising, that Irving’s genius is nearly forgotten today even though he was the first American to be an international superstar, famed on both sides of the Atlantic. He is mostly known only through his authorship of Rip van Winkel and The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, both of which works are rarely presented in their original written form, but almost always in shortened illustrated versions for schoolchildren from publishers convinced of their audience’s stupidity.

Irving is rarely in the limelight these days, but First Things Online recently published an informative article, “Washington Irving and the Specter of Cultural Continuity” by one Eric Seddon, that is well worth reading.

His first book, Dietrich Knickerbocker’s History of New York, capitalized on the amnesia of New Yorkers by a mix of biting satire and real history of the Dutch reign in Manhattan. The book is foundational to any study in American humor. It is wild, free, self-deprecatory, and merciless to the public figures of his day, and by turns lyrically funny, absurd, and reflective. Without it, we might wonder whether American humor, from Twain to the Marx brothers to Seinfeld, would have taken the particular shape it did.

When Americans, always prone to utopian daydreams, were in danger of taking themselves far too seriously, when the term “manifest destiny” was embryonic, Dietrich Knickerbocker rolled his bugged-out eyes, chuckled gruffly, and whispered into the ear of a young nation, “Remember thou art mortal.” […]

Irving’s two most famous stories are to be found in The Sketch Book, virtually bookending the text: “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” In “Rip Van Winkle,” Irving whimsically pointed out the hazards of the new Republic, that a once humble acceptance of life under monarchy could easily give way to arrogant corruption, vice, and the nauseating specter of being governed by village idiots with a gift for demagoguery. […]

The final warning of the book comes in the form of a Headless Horseman, who is either a real ghost of the Revolution or the town bully in disguise, and who targets, of all people, the schoolmaster (even small towns have their intelligentsia). Is it history chasing Icabod Crane, the puritanical teacher obsessed with stories of witch hunts, or just Brom Bones scaring him out of town? Irving doesn’t say, and perhaps our answers tell more about ourselves than about him.

Washington Irving spent his last days in Tarrytown, near the setting of his most famous story. He was a member of the local Episcopal Church, tried to revive the old Dutch festivities on St. Nicholas Day, and was moved to tears by singing the Gloria. In particular he loved to repeat the words “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, and good-will to men.” Though his era was in many ways a bigoted one, he resisted and thereby helped to shape a better future. One of his last revisions to Knickerbocker came late, removing the anti-Catholic references its youthful version contained. He was a man who had seen his share of specters, to be sure, but who didn’t believe they were the strongest reality.

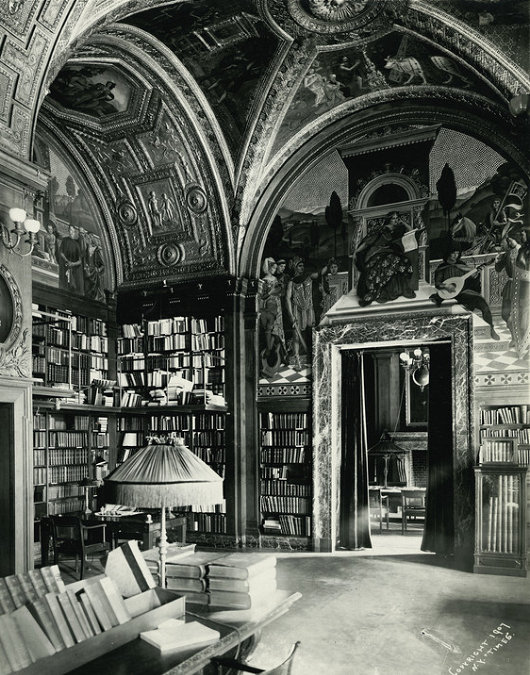

The Finest Library in All New York

Or is it in all the New World?

I do miss my two libraries in Manhattan, the Society Library on 79th Street and the Haskell Library at the French Institute on 60th. Neither of them, however, are fit to shine the boots of the library of the University Club on 54th & Fifth. Architecturally and artistically, it is undoubtedly the finest library in New York. But does it have an equal or a better in all the New World? The BN in BA certainly isn’t a competitor.

West End Collegiate Church

One of my good friends, who is amongst the most loyal denizens of this little corner of the web, found our post on St. Nicholas Collegiate Church of great interest because his son attended the Collegiate School, the oldest school in North America (founded in 1628, and formally incorporated ten years later). The Collegiate School is part of the same complex as the West End Collegiate Church on the corner of West End Avenue & 77th Street on the Upper West Side. The church & school buildings were designed by McKim Mead & White in a Dutch Renaissance Revival style, and handsomely executed.

One of my good friends, who is amongst the most loyal denizens of this little corner of the web, found our post on St. Nicholas Collegiate Church of great interest because his son attended the Collegiate School, the oldest school in North America (founded in 1628, and formally incorporated ten years later). The Collegiate School is part of the same complex as the West End Collegiate Church on the corner of West End Avenue & 77th Street on the Upper West Side. The church & school buildings were designed by McKim Mead & White in a Dutch Renaissance Revival style, and handsomely executed.

THE ARCHITECTS modelled the church after the seventeenth-century Vleeshal (meat market) of Haarlem in the Netherlands. The story goes that, during the Second World War, a handful of Collegiate grads serving together in the U.S. Army participated in the liberation of Haarlem, stumbled upon the Vleeshal and said “Hey, that’s our school!”

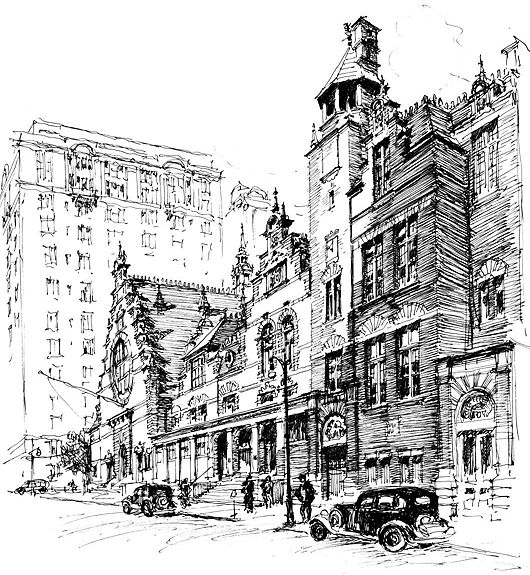

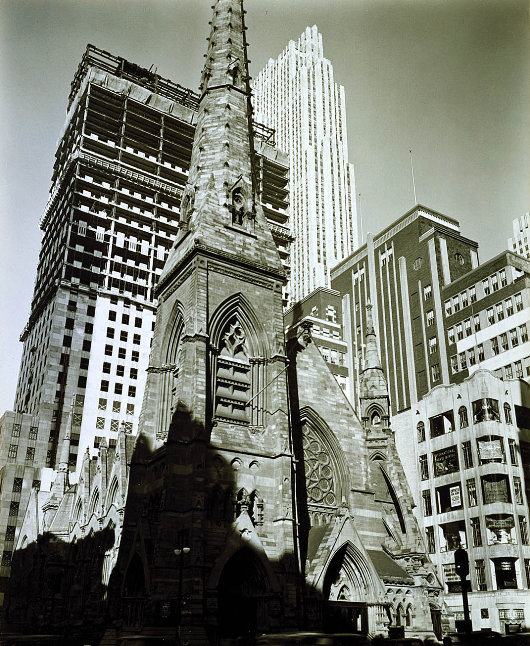

New York’s Dutch Cathedral

The Collegiate Church of St. Nicholas, Fifth Avenue

Dedicated a hundred-and-thirty-six years ago, the Collegiate Reformed Protestant Dutch Church of Saint Nicholas on the corner of Forty-eight Street & Fifth Avenue (photographed above by Berenice Abbott) was for many years regarded as the most eminent Protestant church in New York. The Collegiate Reformed Protestant Dutch Church is the oldest corporate body in what is now the United States, having been founded at the bottom of Manhattan in 1628 and receiving its royal charter from William & Mary in 1696. Now part of the Reformed Church of America, the Collegiate Reformed Protestant Dutch Church is actually a denomination within a denomination, and the remaining Collegiate Churches of New York tend to preach a sort of “Christianity Lite”. (The famous Norman Vincent Peale, author of The Power of Positive Thinking and one of the paragons of the “finding a religion that doesn’t interfere with your lifestyle” school of thought, was the pastor of Marble Collegiate Church at Twenty-ninth & Fifth, where Donald Trump is a member of the congregation).

Remembering the Seventh

It is entirely appropriate that November 11 — Armistice Day — both falls during the month of the Holy Souls and on the feast of St. Martin of Tours. It’s not unlikely that the souls in Purgatory added their voices to plead for peace that November of 1918, and St. Martin, who had himself been a Roman soldier, was no doubt leading the cause from Heaven. (Indeed, his father having been in the Imperial Horse Guards, St. Martin was born into a military family).

67th & Fifth

One of the most remarkable things about these photos from a 1956 Seventh Regiment ceremony are how traditional the buildings in the background are.

Diary

Nothing ever happens in New York, or at least nothing when compared to Edinburgh, London, or Paris; this is my perpetual complaint. But when it rains, it pours, and so it was last night. Not only was it press day, the busiest day of the month-long cycle of creating each issue of The New Criterion, but then the evening beheld both “A Festive Evening Celebrating the Mission of the von Hildebrand Project” at the University Club and “The Reception and Dinner to Present the Medal for Heraldic Achievement” at the Racquet & Tennis Club. The simultaneous events were organized by the Dietrich von Hildebrand Legacy Project and the Committee on Heraldry of the New York Genealogical & Biographical Society, respectively.

A rarely-assembled fun crowd was promised at the von Hildebrand event, but nor was the presentation of the G&B’s medal a common occurrence (there have been only three awarded to date) so I simply resolved that I would do my best to attend both. (more…)

The New York Central Building

The New York Central building once presided majestically over an equally elegant Park Avenue, which is cleverly directed through the building from the south, emerging through the double arches on the north side. Sadly, while the tower (now known as the Helmsley Building) still stands, the view of it has been marred since 1963 when the Pan Am building was built between it and Grand Central Terminal. When it opened, the Pan Am building was the largest commercial office building in the world, and it was certainly one of the least graceful. The 1960s and 70s were not kind to Park Avenue on either side of Grand Central, and many of the traditional-style buildings have been demolished or re-clad in glass.

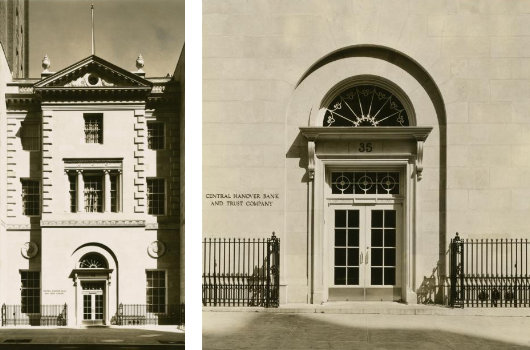

The Hanover Bank: A Classical Gem

No. 35, East Seventy-second Street

Passing by, as I sometimes do, the Chase branch bank at East 72nd St., I think to myself “There’s a fine establishment, in which I should keep my money”. The thought never jumps from theory to practice, however, as I am a patriot in everything but finance, and keep my florins safe with the Hongkong & Shanghai Bank instead. Nonetheless, it’s a handsome building, and the Central Hanover Bank & Trust Company should be commended for erecting it. Central Hanover merged with the Manufacturers Trust Company in 1961 to form Manufacturers Hanover (“Manny Hanny”), which was taken over by Chemical Bank in 1991, which was acquired by Chase Manhattan Bank in 1995, which merged with J.P. Morgan in 2000, and the consumer & commercial banking arm of J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. is now simply known as “Chase”.

While the original Chase National Bank was only formed in 1877, with all these mergers and acquisitions, “Chase” can now trace its lineage back to the foundation of the Bank of the Manhattan Company in 1799, the second oldest bank after the Bank of New York. But — would you believe it? — “Chase” is now headquartered not in the hallowed caverns of Wall Street but — wait for it — Chicago, Illinois!

Let Louis XVI Rest in Peace; A Funeral Mass in Manhattan

By PETER STEINFELS | The New York Times | July 17, 1989

They came not to praise the French Revolution but to bury it.

In the place of tricolor bunting, there were the black vestments of an old-fashioned Roman Catholic funeral Mass. Instead of fireworks, there were the flickering candles of a Manhattan church. Instead of the “Marseillaise,” there was the rise and fall of Gregorian chant.

They came not to praise the French Revolution but to bury it. In the place of tricolor bunting, there were the black vestments of an old-fashioned Roman Catholic funeral Mass. Instead of fireworks, there were the flickering candles of a Manhattan church. Instead of the “Marseillaise,” there was the rise and fall of Gregorian chant.

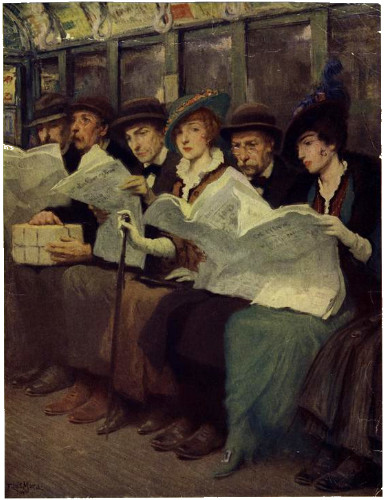

Subway riders, New York City, 1914

Francis Luis Mora, Subway riders, New York City, 1914

Print, 12½” x 9¼”

1914, New York Public Library

The Great Club Revolution

What with all this democracy things will never be the same

The Union Club |

By Cleveland Amory

American Heritage, December 1954, Vol. 6, Issue 1

In 1936 in New York City there occurred the 100th anniversary of the Union Club, oldest and most socially sacrosanct of New York’s gentlemen’s clubs. From all parts of this country and even from abroad there arrived, from lesser clubs, congratulatory messages, impressive gifts and particularly large offerings of floral tributes.

At the actual anniversary banquet, however, as so often happens in gentlemen’s clubs, there was, despite the dignity of the occasion, the severe speeches and the general sentimental atmosphere, a little over-drinking. And one member over-drank a little more than a little. Shortly before dessert he decided he had had enough, at least of the food, and he disappeared. Furthermore, he did not reappear.

Worried, some friends of his decided, after the banquet, to conduct a search. The faithful doorman in the hooded hallporter’s chair gave the news that no gentleman of that description had passed out, or rather by, him, and the friends redoubled their efforts. High and low they combed the missing member’s favorite haunts—the bar, the lounge, the card room, the billiard room, the locker room, the steam room, etc. One even tried, on an off-chance, the library. There, as usual, there was nothing but a seniority list of the Union’s ten oldest living members and a huge sign reading “SILENCE.”

Finally, in one of the upstairs bedrooms, they found the gentleman. He was lying on a bed, stretched out full length in his faultless white tie and tails, dead to this world.

A Rundbogenstil Library in New York

The handsome former Astor Library on Lafayette Street

One of my favorite buildings in all New York is the former Astor Library on Lafayette Street in Greenwich Village. Now the Public Theater, it is a superb example of the nineteenth-century German neo-romantic Rundbogenstil (“round-arch-style”) and one of the few remnants of that style in New York. The Astor Library was the legacy of John Jacob Astor, whose will provided for its establishment. Late in the nineteenth century, the Astor Library agreed to merge with the Lenox Library and the Tilden Trust to form the New York Public Library, one of the greatest libraries in the history of civilization. The building was bought by the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society who tore out the book stacks and used it as a processing station for needy newcomers. In 1965, the HIAS sold it on to a developer who planned to demolish it, but, through a massive civic effort, Joseph Papp and his New York Shakespeare Festival purchased the building and turned it into the Public Theater.

Hic mihi patria est

The Fourth of July, we are told, is a day for celebrating the love of one’s country. Robert Harrington and I were sitting around one evening when we decided to found a guerrilla group. First, it needed a name; Front pour la libération de notre terre sacrée Amérique (or the FLNTSA) was a runner-up but we settled on the Village Green Preservation Society. Frowning upon the camouflage fatigues of most groups of this nature, we decided that our uniform would consist of tweed jackets, flat caps, and balaclavas.

But as our conversation continued we discovered, to our chagrin, that though we thought we were both from the United States of America, we were actually from entirely different countries. Robbo’s country is the nicer, rather horsey part of New Jersey near Princeton, whereas my homeland is mostly the part of New York between the Hudson and the Sound. We discovered we were fighting for the preservation of entirely different Village Greens, and that ma terre sacrée Amérique was entirely different from sa terre sacrée Amérique.

This is one of the problems of a “country” as large as the United States. I love my country, but what do I care about Montana or Texas or Alaska? I wish them well, to be sure, but they hardly seem to have much to do with my country. I once started to read a scaremongering article about the growing Mexicanization of California but I had to put it down after a few paragraphs because it didn’t seem to be anything I had to worry about. If southern California secedes and tries to join Mexico, well good for them! I’ll send them a bottle of champagne and get back in my hammock.

In The Napoleon of Notting Hill, Chesterton wrote:

In that spirit, I present to you below a map of my country, from Sleepy Hollow in the north, to Governors Island in the south. It is a mere approximation, as the borders are both indefinite and ever-shifting. Though highly populated, it is a bit on the small side, and I think I agree with Chesterton that that’s a good thing.

Abomination

This act of willful cultural vandalism is noxious in the sight of both God and Man and is a complete and utter abomination. Whoever is responsible for this should be hanged, drawn, and quartered, and buried at a crossroads with a stake through his heart.

Observe the beauty of this building at the corner of Harrison & Penn in Williamsburg, Brooklyn: its classic composition, its complete vernacular ease. And look at the cheap, tawdry, wrongly-colored brick used to hide and ultimately destroy this ordinary gem.

How can the perpetrator of this act sleep at night? It boggles the mind…

From “A Suburban Country Place”

Claremont, at the end of Riverside Drive, near the tomb of General Grant, suggests in a rather humble way what these mansions were, and in a very magnificent way what their outlooks were. Others linger, desecrated, here and there, closely pressed by new-laid brick and stone. And away up at the extreme tip of Manhattan there are still a few quiet, shady places which may call themselves suburban in the old and honorable sense. But everywhere else around the outskirts of Manhattan the term has gained an unattractive, hybrid meaning. To speak it with pleasure, New-Yorkers must apply it to those remoter regions which can be reached only by a railway journey of considerable length. And then it is incorrectly applied, for a real suburban place is rural in aspect, but urban in convenience — private, green, and peaceful in itself, yet close in touch with the true self of the town. …

“A Suburban Country Place”

The Century Magazine,

May 1897

Glass-plating the Coliseum

1775 Broadway, formerly the home of Coliseum Books (which I believe got its name from the splendid columns ringing the first two floors, as well as from the nearby now-demolished New York Coliseum), is to be glass-plated and re-addressed as “3 Columbus Circle”. As John Massengale commented, “Because if there’s anything New York City needs it’s another glass-covered office building…”.

New Yorker Elected Mayor of London

Congratulations to that most-honoured son of the Empire State, Mr. Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson MP, more commonly known as Boris, on his election to the mayoralty of Greater London. Mr. Johnson was born on these sacred shores some forty-four years ago on a pleasant June day. Boris has politics in the blood as his father Stanley is a former Conservative MEP, but let us hope he does not take after his great-grandfather, Ali Kemal Bey, who made enough unfortunate decisions during his brief tenure as interior minister of the Ottoman Empire that he was knicked from the barber shop of the rather-smart Tokatlian Hotel in Constantinople and lynched shortly thereafter.

Strangely enough, this is not exactly the closest connection New York and London have ever had. Sir Gilbert Heathcote, 1st Baronet was Lord Mayor of London in 1710 while his brother Caleb Heathcote was Mayor of the City of New York, exhibiting how interconnected our transatlantic British world was in those days. Caleb Heathcote was also Lord of the Manor of Scarsdale, which is just five minutes north of here on the train. Created in 1703, Scarsdale was the last manor granted in the entire British Empire. There were about a dozen manorial lordships here in New York, bringing the proud heritage of feudalism to the New World. The Manor of Gardiner’s Island survives to this day as the only manor in America in which the land is still entirely owned by the descendants.

The bulk of manorial privileges (incorporating the pre-existing patroonships from the olden Dutch days) were, alas, abolished in the 1840s, with the final holdouts taken care of in some legislation of 1911, but the Lord of the Manor of Pelham was presented with a fatted calf each St. John’s Day from the City Council of New Rochelle (honoring the Huguenots’ agreement purchasing the land from the Pells) well into the twentieth century.

The Heathcote name survives, in Derbyshire I believe, but not in America. Caleb Heathcote married the daughter of Col. William Smith, Chief Justice of the Province of New York, but had only daughters.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories