Military

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

A Christmas Gift from the Governor

Just in time for Christmas: some excellent news for the Knickerbocker Greys.

Her Excellency the Governor of the great Empire State of New York has signed into law a requirement that this venerable Manhattan cadet corps be allowed to remain in its quarters at the old Seventh Regiment Armory (as The New York Sun reports).

Over recent years the Park Avenue Conservancy has restored the building — a gem of American architecture and interior design — but also effectively expelled the military units still based at the Armory.

The Greys managed to hold out in their “800-square-foot broom closet” (as the New York Post described it) but the Conservancy moved to evict the youth group in 2022. The Greys have fought the eviction in court.

In June a bipartisan bill guaranteeing the Knickerbocker Greys “access and use for permanent headquarters” of the Armory “for the purposes of programming during periods which are not periods of civil or military emergency” passed in the State Assembly and Senate but has only now been signed into law.

The hope is this new legislation will persuade the Conservancy to drop their eviction proceedings which the Greys have been challenging.

Season’s Greetings from the Seventh

Alas, the Seventh Regiment Mess is no more, though we had a few family Christmas-time (and other) celebrations there in its final years.

Happy days when Linda MacGregor was at the helm of it.

A Prize for the General

France’s Top Military-Literary Prize Awarded to François Lecointre

IT SHOULD surprise no-one that the French Army awards an annual prize for military literature. Since 1995, the Prix littéraire de l’Armée de terre – Erwan Bergot is awarded every year for “a contemporary work of French literature that demonstrates active commitment, of a true culture of audacity in service to the collective whole” and is named in memory of the paratrooper officer, writer, and journalist Erwan Bergot (1930-1993).

This year’s prize has been awarded to Gen. François Lecointre, the former Chief of the Defence Staff who now serves as the Chancellor of the Légion d’honneur.

This year’s prize has been awarded to Gen. François Lecointre, the former Chief of the Defence Staff who now serves as the Chancellor of the Légion d’honneur.

A graduate of Saint-Cyr, Lecointre’s book Entre Guerres (Between Wars) relays his long service to France in the land forces, including operations in Central Africa, Rwanda, Bosnia, the First Gulf War, and elsewhere.

As a young captain in Bosnia, Lecointre was concerned when his company lost radio contact with the French UNPROFOR observation post on Vrbana bridge early on the morning of 27 May 1995. When he went himself to investigate, Captain Lecointre discovered that Bosnian Serb soldiers in captured French uniforms had seized the post and taken French soldiers hostage.

Lecointre immediately informed Paris, where President Jacques Chirac circumvented the UN chain of command in Bosnia by allowing soldiers under Lecointre’s command to retake the post on the northern end of the bridge with a bayonet charge that overran the Serb-held bunker. Vrbana bridge is believed to have been the last bayonet charge of any French military operation to date.

General Pierre Schill, Chief of the Army Staff, awarded his comrade-in-arms the Prix Erwan Burgot this weekend. The prize includes a monetary award of €3,000 which Gen. Lecointre has donated to the association Terre Fraternité that provides support to France’s wounded soldiers and their families.

Entre Guerres had already won the Prix Jacques-de-Fouchier awarded by the Académie française earlier this year. (Above: Gen. Lecointre with the académicien, lawyer, and writer François Sureau.)

The Erwan Burgot prize’s jury was chaired by Gen. Schill and included the son and widow of Erwarn Burgot, alongside Col. Loïc de Kermabon, Col. Noê-Noël Uchida, the journalist and writer Guillemette de Sairigné, literary figure Laurence Viénot, Général de Division Jean Maurin, Général de Brigade Gilles Haberey, prix Goncourt winning novelist Andreï Makine, writer Christine Clerc, former head army medic Dr Nicolas Zeller, journalist Jean-René Van Der Plaetsen, Professor Arnaud Teyssier, and the historian François Broche.

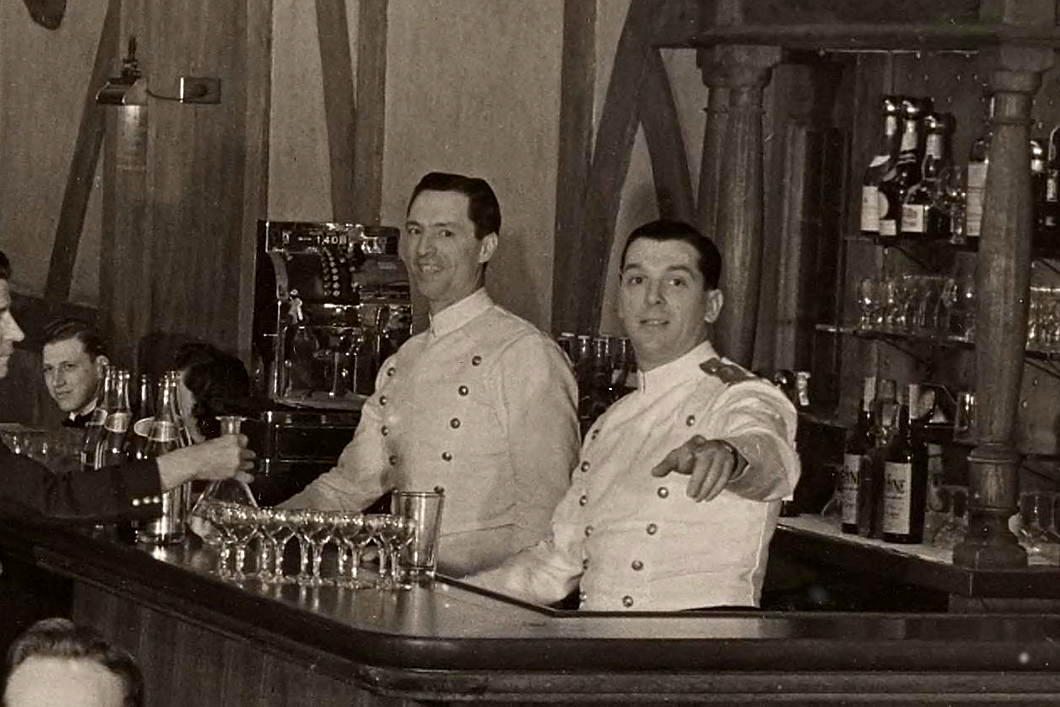

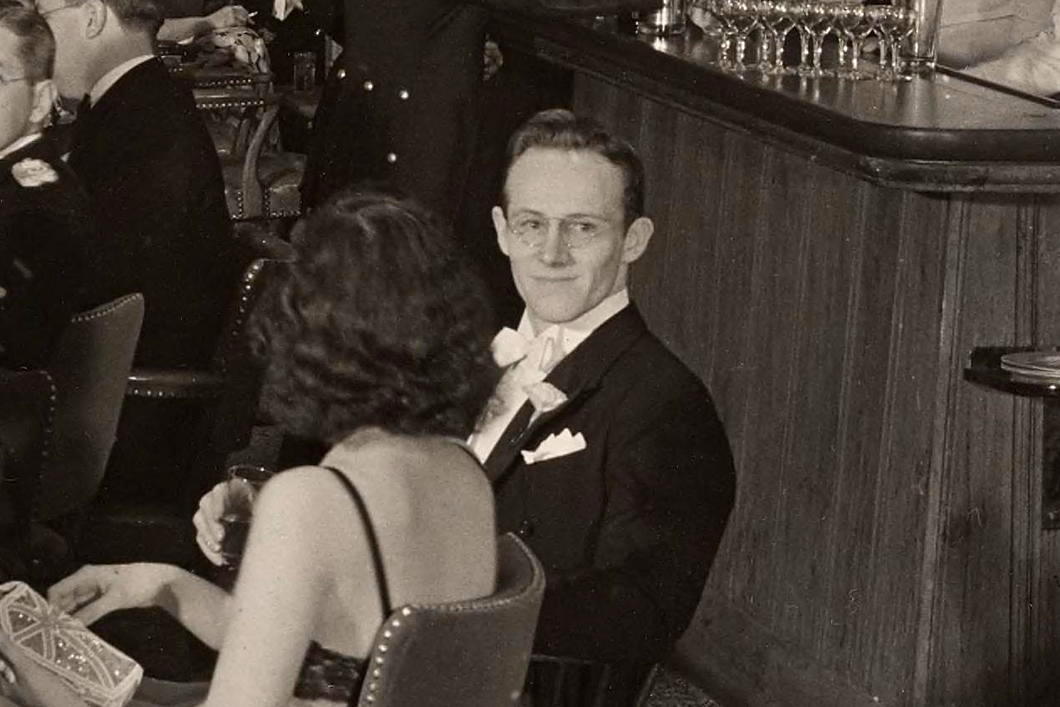

Messing About in Old New York

In the collections of the New-York Historical Society there is a photograph deposited amidst the archives of the Seventh Regiment Gazette.

The scene is the Appleton Mess of the Seventh Regiment Armory on Park Avenue, where Company B of the “Silk-Stocking Regiment” was celebrating its one-hundred-and-thirty-fourth birthday.

It was May 1940. The other side of the Atlantic Ocean, British troops were evacuating from Norway, sparking the debate in the House of Commons that would lead to Winston Churchill being appointed Prime Minister.

But on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, all was still peaceful and calm.

With a packed calendar of events, the social life of B Company was as much of a whirl as any other in the Seventh Regiment.

“The members of the Second Company greeted the onrushing spring with a cocktail party and dance on the afternoon of February 11th,” the Gazette reported. “The time-stained rafters of the Veterans Room echoed back as melodious a medley of sweet, swing, and hot as these old ears have heard in many a year.”

“The spaghetti lovers are still meeting down at Tosca’s on Tuesdays,” the Gazette continued. “All members who drop in on this crowd are warned beforehand to eat fast and keep an eye on their plate. A darting fork awaits all unwatched portions and men have been known to sit down to a full dish of Italian cable only to arise half famished.”

Company B’s Entertainment Committee also found time for a Supper Dance at the end of March that year: “When Charley Botts heard ‘In The Mood’ he gathered up the jitterbugs and sent them scampering around in a breathless Big Apple, much to the delight of the wiser and unbruised amongst us who resisted his wiles.”

“Several of the more energetic members closed the evening by visiting that well-known late spot, the Kit-Kat Club, and are now offering mortgages on the family homestead to settle future bills.”

All the faces, the mode of dress — it’s a picture of a vanished New York, a year and a half before the attack on Pearl Harbor. (Incidentally, December 7, 1941 was also the day Col. Cusack — aka ‘Uncle Matt’ — was baptised.)

On another level, it looks just like the Seventh Regiment Mess I knew from my childhood, when it was in the firm but welcoming hands of Linda MacGregor.

The building has been restored physically but since the military was kicked out it is a beautiful but lifeless hulk, preserved as if in formaldehyde and reduced to being a mere “venue”.

Sic transit gloria mundi.

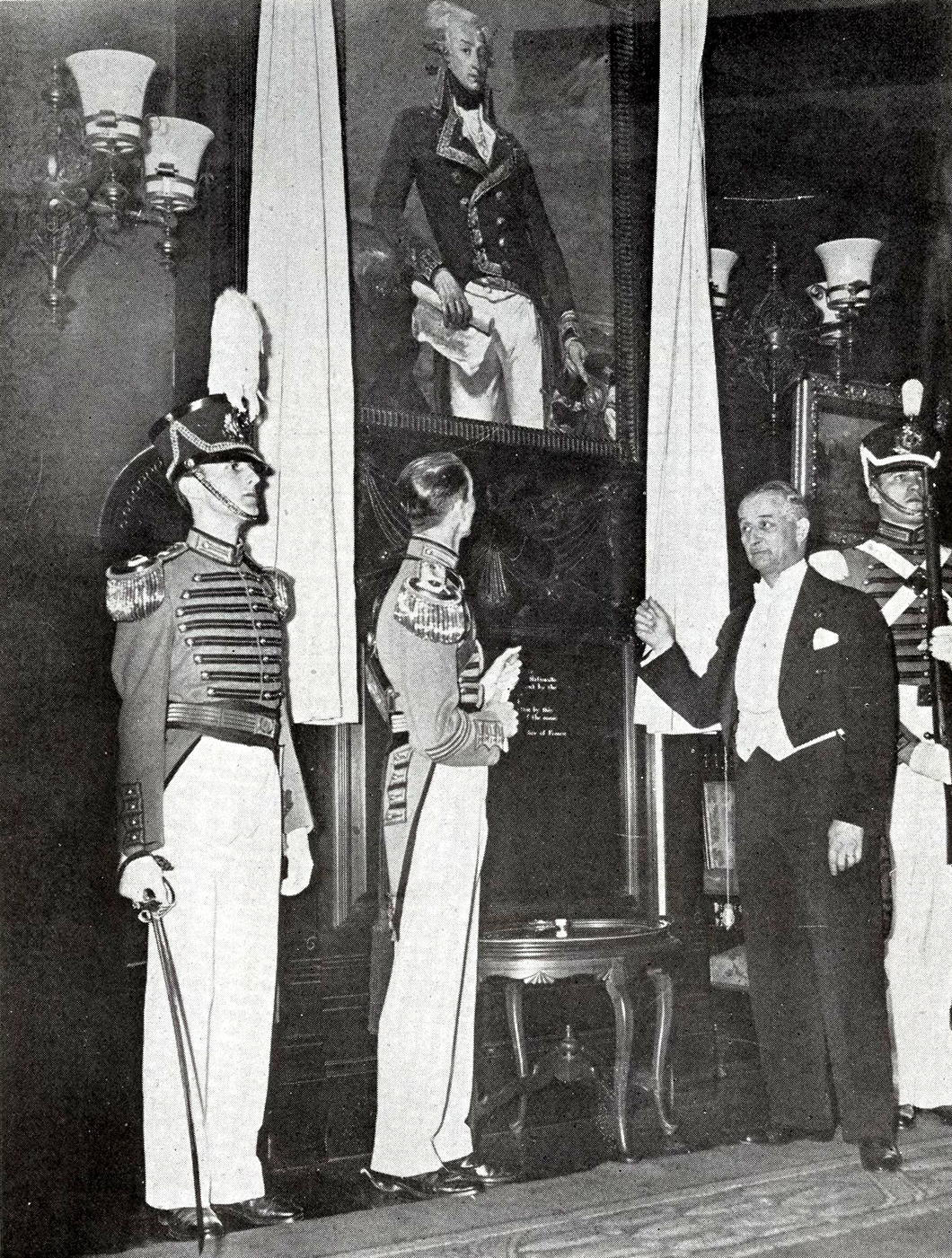

Lafayette at the Seventh

For the first century or so in the history of the United States, there was no more popular Frenchman in America than the Marquis de Lafayette. This nobleman of the Auvergne was an officer in the King’s Musketeers aged 14 and was purchased a captaincy in the Dragoons as a wedding present aged 18 in 1775. Within a year the rebel faction in North America had sent Silas Deane of Groton to Paris as an agent to negotiate support from the French sovereign, but Paris acted cautiously at first.

Lafayette — a young aristocratic freemason and liberal with a head full of Enlightenment ideas — escaped to America in secret and was commissioned a major-general on George Washington’s staff in the last of his teenage years.

Given his relative youth, Lafayette inevitably turned out to be the final survivor of the generals of the Continental Army, and his 1824 trip to the United States solidified his popularity. He visited each of the twenty-four states in the Union at the time, including New York where the predecessor of the Seventh Regiment named itself the National Guards in honour of the Garde nationale Lafayette commanded in France.

This was the first instance of an American militia unit taking the name National Guard, which in 1903 was extended to all of state militia units which could be called upon for federal service.

In honour of this connection and on the centenary of Lafayette’s 1834 death, the French Republic presented the Seventh Regiment with a copy of Joseph-Désiré Court’s portrait of the general that hangs in the 1792 Room of the Palace of Versailles. The Seventh set this in the wall of the Colonel’s Reception Room in their Armory, facing a copy of Peale’s portrait of General Washington.

The privilege of unveiling the portrait went to André Lefebvre de Laboulaye, the French Ambassador to the United States, who was given the honour of a full dress review of the Seventh Regiment on Friday 12 April 1935 before a crowd of three thousand in the Amory’s expansive massive drill hall.

Also present at the occasion was his son François, who eventually in 1977 stepped into his late father’s former role as French Ambassador to the United States. His Beirut-born grandson Stanislas served as French Ambassador to Russia 2006-2008 before being appointed to the Holy See until 2012. In April 2019, Stanislas de Laboulaye was put in charge of raising funds for the rebuilding of Notre-Dame following the fire that devastated the cathedral.

The Irishman at Yorktown

General Charles O’Hara and the Surrender of Lord Cornwallis

Today marks two-hundred-and-forty-one years since the British general Lord Cornwallis surrendered to a joint Rebel-French force at Yorktown in Virginia — perhaps the most embarrassing British defeat until the Fall of Singapore to the Japanese more than a century and a half later.

Every American schoolboy, or indeed any visitor to the United States Capitol, is familiar with John Trumbull’s oil painting of the scene at Yorktown.

Somewhat pitifully, Lord Cornwallis pled ill health and did not attend the formal ceremony of surrender.

Instead, he sent his adjutant to act on his behalf: a wily character by the name of General Charles O’Hara.

O’Hara had soldiering in his blood, being the illegitimate son of a Portuguese woman and Field Marshal the Rt Hon James O’Hara, 2nd Baron Tyrawley and 1st Baron Kilmaine. The elder O’Hara was the sometime envoy-extraordinary to the King of Portugal, where he made the acquaintance of the woman who bore him one of at least three of his sons-born-the-other-side-of-the-blanket.

Lord Tyrawley looked after his son, sending him to Westminster School before buying him an army commission and keeping him close by in the Coldstream Guards which the father commanded himself.

Young Charles was at one point sent on assignment to Senegal commanding a corps of African army convicts which, reading between the lines, may have been a punishing demotion.

He soon regained his command with the Guards though and was sent to America where the royal troops were fighting against a surprisingly cohesive force of rebel English colonists.

Despite being surrounded by numerous American loyalists, O’Hara tended to distrust the colonists and viewed them with suspicion, tarring them all with the brush of rebellion openly practiced only by a distinct (but ultimately successful) minority.

He was wounded at the Battle of Guildford Court House in March 1781, and by the Siege of Yorktown had been promoted to Cornwallis’s second-in-command. (more…)

US Army Chief in London

General James C. McConville, Chief of Staff of the United States Army, dropped into London this week to meet with General Sir Patrick Sanders, who will take over as his British opposite number (Chief of the General Staff) later this year.

Both are the head of their countries’ respective armies and subordinate to overall defence chiefs, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in the US and the Chief of the Defence Staff here in the United Kingdom.

General McConville was welcomed to the official Army Headquarters at Horse Guards, Whitehall, by the Major General Commanding the Household Division, Maj. Gen. Chris Ghika.

A contingent from the Coldstream Guards and the Band of the Irish Guards put together a ceremonial display and Gen. McConville took the salute.

Gen. McConville will also deliver the Kermit Roosevelt Lecture at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst this week.

The general’s visit provided a chance to show off the US Army’s new service uniform — modelled on the popular old pinks and greens.

This provides a much welcome alternative to the Dress Blues which, to my mind, make soldiers look like glorified policemen.

As I wrote when discussing similar changes in Peru, it’s not turning the clock back: it’s choosing a better future.

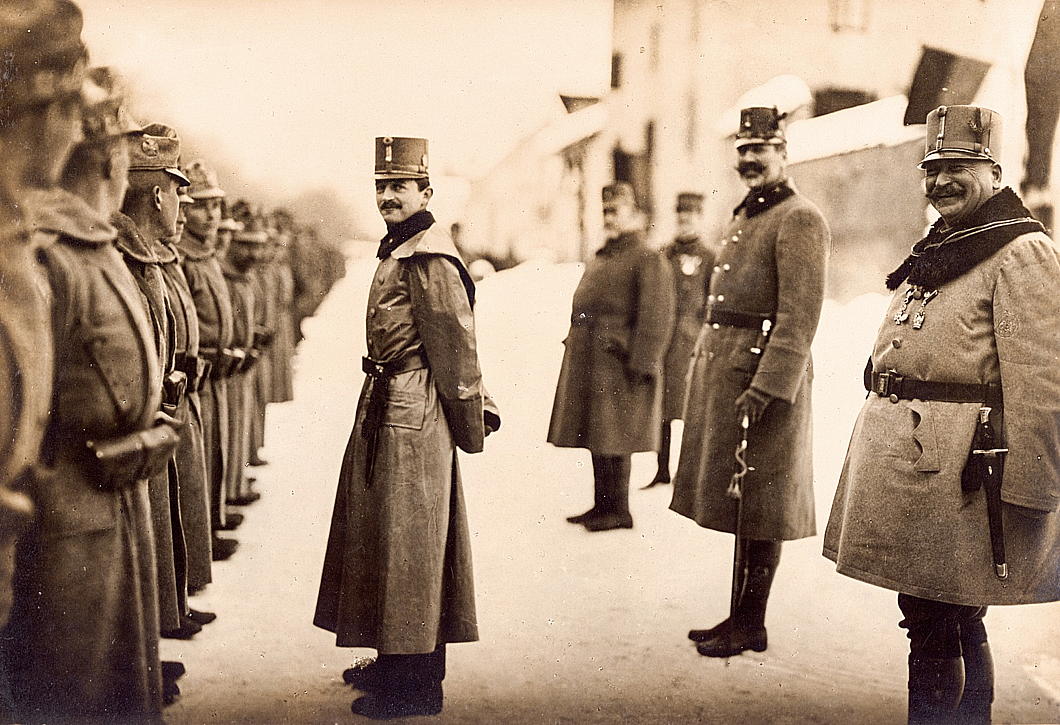

The Saints are Glad

I love this photo of Blessed Charles — here still the heir to the throne — inspecting Austro-Hungarian troops in the Südtirol in 1916.

On the far right of the photograph, Gen. Franz (Ferenc) Rohr von Denta, commander of the Royal Hungarian Army, beams with a massive grin. He looks like a bit of a character.

Next to him is Archduke Eugen, the last Hapsburg to serve as Hoch- und Deutschmeister of the Teutonic Order, which in 1929 was transformed into a priestly religious order.

Franz Joseph would die just months after this photograph was taken.

His grand-nephew and successor Charles would be the last Emperor of Austria, Apostolic King of Hungary, and King of Bohemia — amongst the myriad other titles — to reign (so far).

Hammerstein’s Four Types

Speaking to a friend the other day, I mentioned this quotation which is often incorrectly attributed to Rommel (including by me).

The actual source of these words is Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord, a four-star general of the German army, who described the four types of officer and their place along the axes of being 1) either clever or stupid, and 2) either hardworking or lazy.

There are clever, hardworking, stupid, and lazy officers. Usually two characteristics are combined.

Some are clever and hardworking; their place is the General Staff.

The next ones are stupid and lazy; they make up ninety percent of every army and are suited to routine duties.

Anyone who is both clever and lazy is qualified for the highest leadership duties, because he possesses the mental clarity and strength of nerve necessary for difficult decisions.

One must beware of anyone who is both stupid and hardworking; he must not be entrusted with any responsibility because he will always only cause damage.”

I am sure the experience of many would confirm that Hammerstein’s typology is also applicable in the civilian world.

Hammerstein was a brave man, who unsuccessfully attempted to see President Hindenburg personally in the hopes he would intervene to stop the massacre on the Night of Long Knives.

His friend and regimental comrade General Kurt von Schleicher, the last Chancellor of Germany before Hitler’s appointment, was among those murdered on the evening and Hammerstein defied army orders by attempting to attend Schleicher’s funeral only to be stopped by the SS.

His friend and regimental comrade General Kurt von Schleicher, the last Chancellor of Germany before Hitler’s appointment, was among those murdered on the evening and Hammerstein defied army orders by attempting to attend Schleicher’s funeral only to be stopped by the SS.

Nonetheless, his reputation and skill ensured he was given command during the war, although Hitler later personally dismissed him for his opposition to national socialism.

As Hammerstein was dying of cancer in 1943 he told the art historian Udo von Alvensleben-Wittenmoor: “I am ashamed to have belonged to an army that witnessed and tolerated so many crimes”.

His family refused to allow Hammerstein to be buried with a military funeral as it would have meant his remains being draped in the swastika flag.

Despite being a conservative Protestant nobleman of the old school, two of his five children ended up as communists, though his youngest son became a Protestant theologian.

Portsmouth Pachyderm

Leach (centre) on being made cadet captain at the Royal Australian Naval College in 1944

A delightful episode is relayed in the Daily Telegraph’s obituary of the late Vice-Admiral David Leach of the Royal Australian Navy.

Leach was the last RAN Chief of Naval Staff to have served in the Second World War but the incident in question dates from the 1950s when he was at the gunnery school in Whale Island in Portsmouth Harbour here in England:

In 1955 he was the course officer for a class of sub-lieutenants who decided to have some fun on their last morning parade, on April 1, by bringing a circus elephant on to the island. The duty officer, warned of the elephant’s approach by the bridge sentry, thought that his leg was being pulled and gave the order to let the pachyderm proceed.

Subsequently the class marched on to the parade ground with the elephant in their midst, surmounted by a mahout dressed as a sub-lieutenant. The beast, being well-trained, picked up the band’s marching step nicely, but Captain “Bunjey” Rutherford, the saluting officer in command of Whale Island, was not amused.

Leach had not been party to the April Fool’s joke, but later that morning, when he took the class results to the captain, he had placed Sub-Lieutenant L E Fant at the top. Rutherford was still not amused, demanding “Fant? Fant? Who’s this feller, Fant?” When the news reached the Admiralty, the Second Sea Lord took a personal interest and called Rutherford to announce, somewhat unkindly: “This is a trunk call.”

R.I.P.

Inside Governors Island

This intriguing little island in New York Harbour has always held something of a fascination for me — viz. articles previous on the subject. Aside from its interesting history there is the matter of the complete lack of foresight in ending its military use as well as the failure to imagine a future use suitable to its history and, if the word is not hyperbole, majesty.

Gothamist recently featured a new peek inside some of the abandoned buildings on Governors Island, a mere selection of which are reproduced here. (more…)

“Get me ze Führer!”

Stereotypes of Nazi generals in British war films

“The reason for my uniform being a slightly different colour to yours

is never explained.”

The British are, of course, obsessed with the Nazis. There are many reasons for this, amongst which we must include the large number of really quite good war films produced during the 1950s and 1960s.

For some indiscernible reason these movies have the virtue of being eternally rewatchable and many a cloudy Saturday afternoon has been occupied by Sink the Bismarck!, Where Eagles Dare, or The Colditz Story.

The genre also deploys with a remarkable regularity a number of familiar tropes of ze Germans which the above clip from a British comedy sketch programme (introduced to me by the indomitable Jack Smith) aptly mocks.

The French Way of War

I’ve  been reading Lartéguy recently so was intrigued to hear of another French writer formed by his military experience, Pierre Schoendoerffer (right).

been reading Lartéguy recently so was intrigued to hear of another French writer formed by his military experience, Pierre Schoendoerffer (right).

In a tweet, the cigarette-smoking Helen Andrews shared an article called What a 1963 Novel Tells Us About the French Army, Mission Command, and the Romance of the Indochina War.

I dislike the romanticism surrounding the magnificent losers vs. ugly victors dichotomy – a magnificent victory is infinitely preferably to both. Hence why my natural Jacobite sympathies are highly qualified by complete and utter disdain for Charlie’s unwillingness to see the task through. (An easy judgement when made from centuries of hindsight, I’ll concede.)

Anyhow, I sent the article to The Major and he proffered this reply:

I was going to say something snide about the French army but to be quite honest I have thought for some time that it is rather better than ours [Ed.: the British]. Their officers are tougher, harder, and more professional than ours – those I encountered professionally certainly were. They are also not infected by the political correctness which is wrecking/has wrecked our army (among other factors).

The distinction between the colonial army and the large conscript army at home is valid. It was the conscript army which was defeated in 1870, 1914, and 1940… not the colonial army to which the modern French army now looks.

It is also true that the US Army don’t do Mission Command well. The Marines on the other hand…

Meanwhile back in the States the prolific Ken Burns has done an eighteen-hour documentary on the Vietnam conflict which allegedly ignores all the scholarly input of the past two decades. Nevermind, we just regret it won’t feature the late great Shelby Foote, who (in Burns’s ‘The Civil War’) spoke with such assurance you imagined he was there.

South African VCs in the Russian Civil War

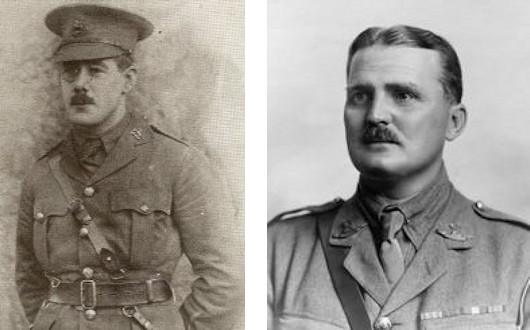

The South African contribution to the Russian Civil War is not very well known, nor particularly well researched by historians of the period. Several South African officers who found themselves in Europe by the time of the armistice ending the Great War volunteered to serve in Russia fighting the Bolsheviks — either with the Allied force there or with the White forces themselves.

Among the South African volunteers were two winners of the Victoria Cross — Major Oswald Reid (above, left) of Johannesburg, and Lt Col John Sherwood-Kelly (above, right) from the Eastern Cape.

The South African aviation pioneer K R van der Spuy — who ended up a major general — managed to serve from the early days of 1914 all through the First World War. His engine failed in Russia, however, and he was taken prisoner after a forced landing in Bolshevik-held territory. The Soviets released him from imprisonment in 1920.

As Cdr W M Bisset wrote elsewhere: “Despite the harshness of the Russian winter and the growing prowess of the Red Army, South African officers were able to make a valuable contribution to the operations of the Allied and White Armies which is well illustrated by the important posts which they held and the awards they received.”

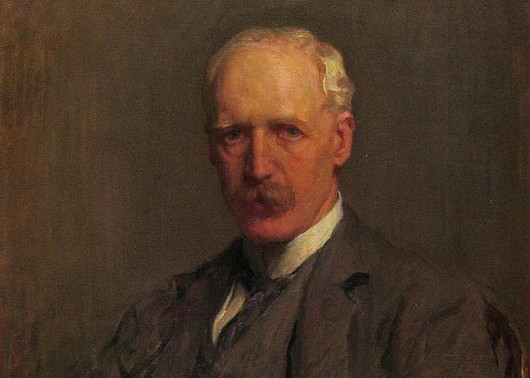

Colonel Moore

Senator Colonel Maurice George Moore, Companion of the Order of the Bath, is an understudied figure from that remarkable period of rapid transformation in Ireland’s political history. While certainly far from typical, Colonel Moore’s experience reflects the changing age rather well.

He was born in 1854 at Moore Hall in Co. Mayo where his family — English settlers who had converted to Catholicism — made their home. His father, George Henry Moore, was known as a kind landowner, and when his horse Coranna won the Chester Gold Cup during the height of the Great Famine, the £17,000 winnings were spent on giving each tenant a cow and importing thousands of tons of grain to relieve their hunger. During this dark period, not a single family was evicted from the Moore lands for non-payment of rent, and not a single Moore tenant died of hunger.

Younger son Maurice was educated locally before heading off to Sandhurst and was commissioned a lieutenant in the Connaught Rangers in 1874. The Ninth Xhosa War brought him to South Africa for the first time, also seeing action during the Anglo-Zulu War not much later. Promoted to captain in 1882 and major in 1893 it was the great Boer War (1899–1902) which transformed Moore’s entire world.

As a field commander Moore was highly regarded and proved himself capable at the Battles of Ladysmith, Colenso, Spioen Kop, and Vaal Krantz. His conduct in combat notwithstanding, Moore was appalled by the atrocities committed by his own side against the Boer civilian population — women and children herded into concentration camps where many starved to death while, just beyond the barbed-wire fences, British troops were exceptionally well provisioned. One wonders what effect the stories of the Great Hunger that took place just a few years before his own birth may have had on witnessing these horrible and frighteningly avoidable horrors.

With the Boers finally defeated, Moore ended up a colonel and was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath in honour of his achievements. In South Africa he became fluent in the Irish language having started to learn it from soldiers under his command. Back home in Ireland, Col Moore became active in promoting the study of Irish language and history, whether at evening schools on his family’s estates or in joining Conradh na Gaeilge and supporting compulsory Irish at the National University.

When Óglaigh na hÉireann — the Irish Volunteers (now Ireland’s defence force) — was founded in 1913 his military experience was judged useful and he was appointed to its provisional committee. He opposed Redmond’s takeover bid a year later but nonetheless followed him into the National Volunteers when the split did occur, the Redmondites putting themselves at the disposal of the British forces during the Great War. Colonel Moore’s final break with the constitutional nationalist leader came after the Easter Rising, and he joined Sinn Féin the following year. In 1918 his son Ulick was killed in action during the German’s spring offensive.

Given  Col. Moore’s long experience in South Africa, Dail Éireann appointed him the secret Irish envoy to that country. With the creation of Seanad Éireann in 1922, Col. Moore was appointed a senator and began his legislative career which continued the entirety of the Free State Senate’s existence.

Col. Moore’s long experience in South Africa, Dail Éireann appointed him the secret Irish envoy to that country. With the creation of Seanad Éireann in 1922, Col. Moore was appointed a senator and began his legislative career which continued the entirety of the Free State Senate’s existence.

Starting out in Cosgrave’s ruling Cumann na nGaedheal party, Senator Moore quickly began to oppose the government policy. The Boundary Agreement late in 1925 provoked his defection to the new Clann Éireann (or People’s Party) when it was founded early on in 1926. Just two months later, in March 1926, de Valera founded Fianna Fáil which took on what little momentum Clann Éireann had. Once Dev’s efforts proved their worth at the ballot box in 1928, with voters electing eight Fianna Fáil senators, Col Moore sat with the party in Leinster House.

In 1932, the voters put Fianna Fáil in power for the first of many times and de Valera began his reshaping of the Irish state, culminating in the 1937 Constitution of Ireland that has stood the test of time. Significantly, Ireland is the only successor state to have emerged from the First World War to have preserved its constitutional democracy, and much of this is due to Dev’s instinctive conservative republicanism. When the Constitution came into effect in 1937, An Taoiseach appointed Col Moore to the newly constituted Seanad, and he continued to serve as a Senator up until his death in 1939.

Marinus Willett

In one of the galleries of the Metropolitan Museum’s American wing, behind the Tuckahoe-marble façade of the old Assay Office (moved here from Wall Street), hangs this portrait of Col. Marinus Willett of the Continental Army’s 5th New York Regiment.

Born in 1740, the second of thirteen children, Willett attended King’s College before being commissioned a lieutenant in a New York provincial regiment during the Seven Years’ War (or French and Indian War as it’s known more locally). (more…)

Past and Future Meet in Peru’s Navy

Lima’s Latest Warship Boasts Four Masts and Full Rigging

Today the Peruvian Navy’s newest ship, the BAP Unión, returns to its home port of Callao after an 8,900-mile tour at sea that took in eight countries over 98 days. But though commissioned earlier this year by then-President Ollanta Humala, the Unión isn’t some grey-painted stealth frigate but a four-masted, steel-hulled, full-rigged barque. Named after a corvette that saw action in the War of the Pacific, the Unión was laid down at Callao’s SIMA shipworks in 2010, launched in 2014, and was commissioned this past January as the primary training vessel of the Peruvian fleet.

The unimaginative might be surprised that such old-school ships are being used to train modern sailors, but the Unión’s Commander Roberto Vargas is unambiguous.

“On modern warships, working with computers and satellites all the time, we forget that we have to learn the essentials of sailing,” Commander Vargas told the Miami Herald.

“On a ship like the Unión, these cadets learn leadership, they learn cooperation, they learn group spirit. It’s impossible to work alone with these big sails — you have to work with other people. And most of the basics, like navigation and oceanography, are the same.”

Many other Latin American countries use tall ships as naval training vessels. Argentina’s ARA Libertad was the subject of an attempted seizure by foreign vulture funds seeking payments on debts defaulted upon in 2002.

While most date from the 1960s (Colombia’s Gloria), ’70s (Ecuador’s Guayas; Venezuela’s Simón Bolívar), or ’80s (Mexico’s Cuauhtémoc), Chile’s Esemeralda was launched in 1946. The grande dame of them all is Uruguay’s schooner the Capitán Miranda, launched in 1930 but docked since 2013 awaiting decisions on upgrades.

One analyst notes that even two-hundred years later the old imperial connections are still thriving in the strong Spanish influence on many of these ships:

The Peruvian state-controlled shipyard SIMA (Servicios Industriales de la Marina) constructed the Union in its shipyard in the port of Callao, but the Spanish company CYPSA Ingenieros Navales cooperated in the vessel’s structural design.

As for other ships, many were constructed by Spanish companies. For example Colombia’s Gloria, Ecuador’s Guayas, Mexico’s Cuauhtemoc, and Venezuelan’s Simon Bolivar were all manufactured by Astilleros Celaya S.A., while Chile’s Esmeralda was obtained from the Spanish government which constructed it at the Echevarrieta y Larrinaga shipyard in Cadiz.

One exception to the rule is Brazil’s Cisne Branco, which was constructed by the Dutch company Damen Shipyard.

Given the return to tradition in Peru’s army that we had previously reported on, it’s a pleasure to see this continuing in the country’s navy. Peru continues to show the world that another future is possible.

Entering the old harbour of Havana, Cuba.

Above and below, decked out for commissioning in Callao.

President Humala at the commissioning ceremony.

Best Foot Forward in Peru

A return to tradition for the Peruvian armed forces

One of the results of Peruvian voters electing the left-wing nationalist Lt Col Ollanta Humala as the president of their republic in 2011 has been a renewal of the traditions of the country’s armed forces – under this Excelentísimo Señor Presidente there has been a return to a much more traditional style of military uniform. A long decline in standards only accelerated during the first presidency of the liberal Alan García (1985-1990) who altered the Changing of the Guard at the Government Palace, while his populist successor Alberto Fujimori had the more pressing task of defeating an insurgency to turn his attention to such matters.

It’s often alleged that cultural trends in the Americas have long been riven by a conflict between one tendency favoruing European influences against another which favours national or indigenous inspiration. This dichotomy seems false, as the Americas are at their best when they take the finest in the European tradition and develop it in a new way with the addition of more local flavours.

In the nineteenth century, however, the European was in the ascendant, and particularly in South American militaries which relied upon European advisors to update and train their armed forces. Countries like Colombia and Chile imported Prussian advisors, which has given their militaries a Teutonic air to this day (viz. Colombia’s pickelhaube and Chile’s parada militar).

In Peru, however, it was the French who were brought in to bring the army up to speed, and that lasting influence is obvious from the uniforms seen here at a recent passing-out ceremony at the Escuela Militar de Chorrillos attended by the President. No pickelhaube here, the kepi reigns supreme.

It’s not turning the clock back: it’s choosing a different future. (more…)

Some Aspects of the Fall of the Fourth Republic

(Only interesting, I’m afraid, to those reasonably acquainted with the situation of France in May 1958)

• The French-Algerian instigators of the military rebellion led by Salan didn’t know what to make of him when he was first appointed to Algeria so they decided, just to be on the safe side, to assassinate him on his first day on the job. Salan survived the bazooka attack on his office but his ADC was killed. The general later became the only socialist freemason to lead a right-wing terror group (the OAS).

• Once the Algiers rebellion commenced and travel between Algeria and metropolitan France was cut, many supporting figures made their way across the Mediterranean by whatever means at hand. Soustelle managed to escape his police guards and get to Algiers via a secretly chartered Swiss plane, but the more romantically inclined Roger Frey — later Minister of the Interior — first tried to get to Algiers on the actor Errol Flynn’s yacht. It didn’t pan out, and instead he was forced to hire the boat of an English ex-naval officer turned smuggler.

• The man in charge of wiretapping French telephones was unsure which side would emerge on top so cautiously refrained from giving the government the full picture of the information his wiretaps revealed.

• When Corsica was seized by the rebels, Moch, the Interior Minister, decided to send in the elite of the police force, the CRS. He was afraid, however, that military transport planes would fly them directly to Algeria, so he was forced to commission Air France planes instead. Upon landing in Corsica, the entire CRS contingent was met by the rebel parachute regiment and immediately defected to the rebellion.

• So widespread was the reluctance to support the government against the military rebels that even the meteorologists send false warnings of storms in the Mediterranean in the hopes of keeping the French Navy from moving against the rebels in Algiers.

• The air force was particularly keen for de Gaulle to take power, and took to flying planes in a Cross of Lorraine formation, as well as sending troop transport planes to Algeria in case they would be needed to invade mainland France.

• Regional military commanders in France varied in their loyalty to the government and sympathy for the rebels. One commander is alleged to have told the regional prefect “M. le Préfet, I am not here to defend your préfecture, but to take it.” Other prefects warned the cabinet that any orders for the police to arrest those suspected of aiding the rebellion might result in the prefects instead being arrested themselves.

• The government had sometimes ordered firemen to unleash their water hoses against rioters in the past. As popular support for the cabinet faded away, the head of the fire brigade felt compelled to inform ministers that his men would not take part in any anti-riot measures but would merely put out any fires that erupted. “And,” he said, referring to the home of France’s National Assembly, “in the Palais Bourbon, they wouldn’t bother.”

• As Philip Williams reports in his article “How the Fourth Republic Died”:

At that night’s cabinet Pleven summed up: “We are the legal government, but what do we govern? The Minister for Algeria cannot enter Algeria. The Minister for the Sahara cannot go to the Sahara. The Minister of Information can only censor the press. The Minister of the Interior has no control over the police. The Minister of Defence is not obeyed by the army.” Said a left-wing Gaullist in the Assembly, “You are not abandoning power — it has abandoned you.”

The Impetuosity of Youth

From the Flickr feed of South Africa’s Etienne du Plessis:

These pictures were taken 2 October 1964: I was the pilot [writes Quentin Mouton]. The pictures are original and not ‘touched up’. The ‘Pongos’ (Army types) were on a route march from Langebaan by the sea to Saldanha. The previous night in the pub one of them had said: “Julle dink julle kan laag vlieg maar julle sal my nooit laat lê nie!” (You think you can fly low, but you will never make me hit the deck). Hullo!!!

I went to look for them on the beach in the morning and was alone for the one picture. I was pulling up to avoid them. In the afternoon I had a formation with me and you can see the other a/c behind me. (piloted by van Zyl, Kempen, and Perold).

A friend by the name of Leon Schnetler (one of the pongos) took the pics. The guy that said “Jy sal my nie laat lê nie!” said afterwards that he was saying to himself as I approached: “Ek sal nie lê nie, ek sal nie lê nie” (I wont go down, I wont go down) and when I had passed he found himself flat on the ground.

Memories from the past.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

- American Exuberant February 10, 2025

- Crux Alba Journal Launch February 10, 2025

- The Year in Film: 2024 February 10, 2025

- Articles of Note: 27 January 2025 January 27, 2025

Most Recent Comments

- on When an American aristocrat meets a European Grand Duke

- on The Year in Film: 2024

- on Jesuit Gothic

- on The Borough Synagogue

- on No. 82, Eaton Square

- on Christ Church

- on The Last Will and Testament of Louis XVI

- on Amsterdam

- on Season’s Greetings from the Seventh

- on Season’s Greetings from the Seventh

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories