Interesting Things Elsewhere

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Articles of Note: 27 January 2025

Recently we welcomed the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, Cardinal Pizzaballa, to London on a visit of several days. He has what must be one of the most difficult jobs in the world, caring for Latin-rite Christians and their neighbours in Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Cyprus, and I think possibly the Sinai as well.

We first met in Jerusalem in 2023, so catching up with him for a second (and then third!) time to hear about the situation in the Holy Land was illuminating, if a bit depressing.

At First Things, Cole Aronson meets the Patriarch and explores his unique and demanding role.

■ The Pantheon in Paris, where secular heroes are entombed either physically or symbolically, presents one of the most intriguing aspects of France’s civil religion.

On the eightieth anniversary of the liberation of Strasbourg, President Macron announced that the academic, army officer, and father of the Annales school of historians Marc Bloch would be elevated to the Pantheon.

In the American Conservative, Luke Nicastro explores France’s newest hero.

■ Along with Frankfurt and Potsdam, Budapest has undergone one of the most comprehensive programmes of urban repair in recent years.

The Financial Times’s architecture critic Edwin Heathcote reports informatively, despite his simplistic conceptual error of slagging off rebuilding as reaction.

I’ll say it again: it’s not turning the clock back — it’s choosing a better future.

■ Candlemas is fast approaching but there’s still a few days left before the Christmas season ends properly.

The old-school Irish Protestant ‘Laudable Practice’ provides an excellent critique of a First Things piece: Old High Christmas Cheer, or Why the Oxford Movement Did Not Save Christmas.

Much good came from the Oxford Movement, but there is a tendency today to underestimate the levels and layers of cultural continuity in England across the centuries.

Laudable gets this right, pointing to how the Georgians celebrated Christmas. Nicholas Orme has written on how the feast of the Incarnation was kept in mediaeval England.

■ Finally, Lord Sumption peeks into the world of espionage in the Middle Ages.

Articles of Note: 12 December 2024

Luttwak first came to my attention when, about 10 or 11 years old, I was given a copy of Coup d’État: A Practical Handbook (I think one of the many I received from my relation Henry, R.I.P.). He has been interesting at every turn I have had to read him or his thoughts ever since.

Santi Ruiz of Statecraft has released a delicious new interview with Luttwak.

“Coups had been very common until about two years after the book was published, and then stopped,” Luttwak contends. “The reason is that authorities everywhere reverse-engineered the book. The book was published in English, and it was immediately translated into about 13 languages. It went all over the place. I think what happened is that people learned to reverse engineer.”

He relates the story of Gen. Oufkir’s attempted coup against Hassan II of Morocco: “Oufkir bled to death, and he did so over a copy of my book.”

Luttwak’s explanation of the Islamic Republic of Iran’s manipulation of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to assert racial dominance over the Arabs is sharp.

■ Ever since school days, we are Argentinophiles. The Financial Times, of all people, has a helpful “long read” examining the surprising successes of President Javier Milei.

■ Dr Katherine Bayford writes on the rift that doomed the American Confederacy.

■ Dan Hitchens reviews the film ‘Conclave’.

■ Niall Gooch is always reliable on railways. He compares Britain’s rail woes with the experience of our continental neighbours and concludes that we are still in for difficulties:

Culture is just so hard to prod in a positive direction; people get stuck in their ways, and find it hard to move the assumptions and perspectives which dominate beyond the station forecourt. Yet, shifting the dial isn’t impossible, if the will is there, and this is yet another arena in which British offerings can improve.

■ The prospective — all though not yet assured — loss of London’s Smithfields Market is a portent of doom for the metropolis, Sebastian Milbank prophesies.

One day, I believe, we will have to reclaim London for England, and create an economics of human flourishing rather than of usurious speculation and rent-seeking.

He is right, of course, and I think this will happen, but the English are slow movers and our political class is pretty immured from the ideas and thinking going on below.

The emerging consensus hasn’t yet reached up to those actually making decisions, and it may be five or ten years before it does. Much more damage can be done in the mean time.

■ “Turning back the clock is proverbially impossible in history,” Wessie du Toit writes, “but apparently not in architecture.” An exploration of the architectural ambitions of Viktor Orban.

■ We are well into the preparatory tide of Advent. The ever-estimable Eleanor Parker reminds of Conditor Alme Siderum, one of the office hymns of this season.

Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

Caro had been a Nieman Fellow at Harvard studying urban planning and land use when he came up with the idea for the book. He thought it would take him nine months, but extensive research and over five-hundred in-person interviews meant it took eight years to complete.

Caro then started working on his study of Lyndon Baines Johnson, the first volume of which emerged in 1982 and the fifth (and final?) one he is still working on. (At the end of the fourth, LBJ had just become president.)

But where does he write? Christopher Bonanos of New York magazine finds out:

It’s an ageless space, one where it could be last week or 1950 inside, matter-of-fact and utilitarian. A couple of bookcases, a plywood work surface, corkboard with outlines tacked up, an old brass lamp, an underworked laptop for emails, a Smith-Corona typewriter. The desk chair is hard wood with no cushion. There’s a saltshaker next to the pencil cup for when Ina brings a sandwich out at midday. The desk has a big half-moon cutout, same as the one back in New York, so he can rest his weight on his forearms and ease his bad back. That arrangement was recommended by Janet Travell, the doctor who grew famous for prescribing John F. Kennedy his Boston rocker. She, with Ina, is a dedicatee of The Power Broker.

He bought the prefab shack, he says, from a place in Riverhead for $2,300, after a contractor quoted him a comically overstuffed Hamptons price to build one. “Thirty years, and it’s never leaked,” he says. This particular shed was a floor sample, bought because he wanted it delivered right away. The business’s owner demurred. “So I said the following thing, which is always the magic words with people who work: ‘I can’t lose the days.’ She gets up, sort of pads back around the corner, and I hear her calling someone … and she comes back and she says, ‘You can have it tomorrow.’”

Does he write out here every day? “Pretty much every day.” Weekends too? “Yeah.” Does he go out much while he’s on the East End? “We have two friends who live south of the highway, and I said to Ina, aside from them, I’m not going this year.” There are other writer friends nearby in Sag Harbor, and they get together, but at this age, Caro admits a little sadly, they’re thinning out. He’ll be 89 this fall.

■ George Grant is a still-underappreciated giant of political thinking in the English-speaking world. He is too little known outside his native Canada, which he sought to defend from the undue overwhelming influence of its sparkling and glamourous southern neighbour. Next year marks the sixtieth anniversary of his Lament for a Nation.

Of all people, a research fellow at Communist China’s Institute for the Marxist Study of Religion — George Dunn — has written a thoughtful introductory overview of Grant’s life and thinking: George Grant and Conservative Social Democracy in Compact.

■ Katja Hoyer mused on an overlapping theme in a recent Berliner Zeitung column which she has helpfully presented in English as well:

A diplomat close to the SPD recently told me that he couldn’t understand why working-class people in particular voted for the AfD. Things weren’t so bad for them, after all. I didn’t bother pointing out that rampant inflation, high energy prices and rising rents have had a hugely detrimental effect on the living standards of people with low and middle incomes because his analysis completely misses the point.

Germany’s working-class voters, Katja argues, feel forgotten by the parties founded to represent them.

■ Since the fall of the Berlin Wall — and earlier in Angledom — political conservatism has effectively been taken over by economic liberalism.

This has denied the centre-right from learning from and deploying useful experience from outside liberalism, with the wisdom of figures as varied as Benjamin Disraeli, Giorgio La Pira, Charles de Gaulle, and Thomas Playford essentially ignored or sidelined.

Kit Kowol’s new book Blue Jerusalem: British Conservatism, Winston Churchill, and the Second World War explores the visionary side of wartime Conservatism. Dr Francis Young offers his take on Tory utopias in The Critic.

■ From a similar era, Andrew Ehrhardt writes at Engelsberg Ideas on Ernest Bevin and the moral-spiritual dimension of British foreign policy.

■ Our friend Samuel Rubinstein has studied at Oxford, Leiden, and the Sorbonne — technically the oldest universities in their three respective countries (although we all know that Leuven is in fact the doyen of Netherlandish academies).

Sam offers an incredibly interesting comparison of the experiences of these three institutions in a humble essay on his Odyssean education:

I arrived in Leiden, armed with my phrase-book, with some ambitions of learning Dutch. The first blow came at the Starbucks in the train station, when the barista answered my Ik wil graag in English without hesitating. The second came the following day when I tried again, at a different café – only this time it seemed that the barista (Spanish? Italian?) didn’t know much Dutch either: even the natives were placing their orders in English. So I gave up – save one hobby, reading Huizinga in the original. I got myself an attractive coffee-table edition of Herfsttij and managed a page or so a day, strenuously piecing it together from my English, German, and smattering of Old English. I still haven’t the faintest idea how to pronounce any of it.

■ And finally, those of us who love Transylvania will enjoy Toby Guise’s summary of the Fifth Transylvanian Book Festival in The New Criterion.

Articles of Note: 17 September 2024

31½ in. x 59 in.; (link)

The Lebanese banker, writer, journalist, and politician Michel Chiha postulated that Beirut was “the axis of a three-pronged propeller: Africa, Asia and Europe”.

The city’s current airport was inaugurated in 1954, towards the height of its golden years.

In L’Orient-Le Jour, Lyana Alameddine and Soulayma Mardam-Bey report on how Beirut Airport’s story reflects the highs and lows of Lebanon’s history. (Aussi en français.)

■ Another one bites the dust: this time it’s London’s Evening Standard — traditionally the most London of London’s daily newspapers — which recently announced it will move to a single weekly printed edition.

In its heyday there were several editions per day, with “West End Final” on rare occasions topped up by a “News Extra” edition.

Stuart Kuttner, a veteran of the Standard, wrote a beautiful paean to the paper published in the Press Gazette.

■ Samuel Rubinstein shows how historians’ war of words over the legacy of the British Empire tells us more about the moral battles of today than shedding actual light on the past.

■ Wessie du Toit explores the curious columnar classicism persistent across the full spectrum of South African architecture.

■ With union presidents speaking at America’s Republic party convention, Senator Josh Hawley explores the promise of pro-labour conservatism.

■ Also at the increasingly indispensible Compact, Pablo Touzon explores how the Argentine left created Javier Milei.

■ Closer to home, Guy Dampier argues that Britain’s public services, housing, and infrastructure have reached their migration breaking point and the new Government has zero solutions.

■ Meanwhile, five hundred academics have signed a joint letter urging the Labour government not to scrap university free speech laws as the Education Secretary announced they will do.

11½ in. x 16½ in.; (link)

Articles of Note: 20 May 2024

British right-liberals are sometimes accused of yearning for “Singapore-on-Thames” but they would, for example, recoil from the state-backed housebuilding that Singapore relies on.

The indomitable Lola Salem visited the flourishing Straits state.

“In everyday life,” she writes, “the state endeavours to demonstrate its relevance and ensure citizens feel that they have a stake in what is achieved in their name.”

But the foundation of Singapore’s undeniable strengths is “a complex tapestry of trade-offs that Western leaders wilfully or inadvertently ignore.”

■ Romania is a delight to visit, but I have only been to Transylvania which is somehow another category entirely. A bit like if you’ve been to Britain, but only (“only”) Scotland.

Christopher Brunet says that Romanians themselves tell foreigners to visit Transylvania and avoid their own capital city. He decided to do the opposite and spent a month as a boulevardier in Bucharest.

Brunet reports back that Romania is quietly doing great.

■ Without meaning to damn with faint praise, David Warren is one of the great Canadians of our age. I long felt an almost spiritual connection to him but, though we have never met in person, I assuaged myself that we were at least infrequent correspondents.

One day I went to check when was the last email I had from him only to be surprised to find that I had never, in fact, corresponded with him at all. So I wrote to him and told him this, which provoked a reply saying that he too had assumed we had written to one another several times. Two mastodons bellowing across primieval swamps, or the Atlantic ocean, or the Canadian border when I was still in New York.

Amongst David’s many accomplishments was the foundation and editorship of The Idler (1985-1993), the greatest Canadian magazine ever printed. Canada generously shovels endless cash at its literary efforts in the hope of producing something homegrown that can survive the onslaught of popular culture from its peaceful neighbours to the south.

Despite critical acclaim and obvious excellence, The Idler’s unfashionable conservatism meant that it never had access to the largesse distributed by the Canada Council for the Arts. As that body funded 96 different publications, David branded The Idler as “Canada’s 97th best literary magazine”.

David writes about his experience editing the review that described its ideal reader as “a sprightly, octogenarian spinster with a drinking problem, and an ability to conceal it”.

19¾ in. x 26 in.; (link)

■ Edinburgh was the site of the second-most venerable legislature in the English-speaking world, and it is worth wending a wander into Old Parliament Hall — one of the city’s three parliament buildings.

We’re all familiar with the way the House of Commons sits, having inherited the antiphonal seating of the old Chapel Royal of St Stephen in the Palace of Westminster.

At Old Edinburgh Reborn, Dr Robert Sproul-Cran has penned a very thorough examination of how seating was arranged in the Estaits of the Realm, the Scots parliament of old.

■ It would take a heart of stone not to be amused by the life and times of King Zog of Albania. He may have been a vulgar gangster but he had a certain flair, and one appreciates the imaginative even when it is self-aggrandising.

Daniel Marc Janes reviews a new book about the Illyrian potentate.

(And if you haven’t read the Albanian writer Ismail Kadare, you should.)

■ The sheer freakishness of American campus life is as fascinating as it is alarming.

The universities of the United States are some of the most influential factors of social control in the world, and whatever weird innovations you experience in your professional or public life worldwide today are usually explained by something that was going on at Yale or Stanford five or ten years before.

Ginevra Davis has written a sad chronicle of Stanford University’s war against social life. They even let an artificial lake go dry to stop people enjoying it!

■ What is more satisfying than the brilliant self-taught amateur who outshines the experts?

John Steele Gordon writes about the great astronomer E.E. Barnard.

■ A new documentary film about South Korea’s founding father, Rob York reports, has led to a newfound appreciation of the much-maligned Syngman Rhee.

■ I am a fan of the neglected postwar American conservative thinker Peter Viereck, and of course everyone is a fan of Metternich. (Viereck was previously mentioned here in January thanks to Samuel Rubinstein.)

Hamilton Craig covers both figures in his suggestion of how Yoram Hazony’s “NatCon” conferences can learn from Austria’s greatest chancellor.

■ I recently wrote about Telephone Kiosk No. 2, but Clive Aslet does it better.

■ Mary Harrington claims that conservatism is dead and the future belongs to right-wing progressives like Bukele.

■ Whoever Pimlico Journal is says we need to stop valorising dead centrist Tories.

■ And it turns out that the role of Patriarch of Constantinople is actually an arms-length Langley job. (Caveat emptor.)

30⅓ in. x 22½ in.; (link)

Articles of Note: 13 March 2024

My then-flatmate was getting married the next day and much pottering-about sorting things was required but the idiosyncratic beauty of this building captured my imagination — part Norman, part Moorish. I was almost insulted that I hadn’t come across it in any of my bookish explorations.

The historian Edmund Harris covers Chideock in his lusciously illustrated post on Recusancy in Dorset and the ‘other tradition’ of Catholic church-building.

■ Generations ago it was said that the three institutions no British politician dared offend were the trade unions, the Catholic Church, and the Brigade of Guards. In 2020s Britain there is only one caste which must always be obeyed: the ageing, moneyed homeowners.

Not only do these “NIMBYs” (“Not In My Back Yard”) jealously guard their freeholds, they do whatever they can to prevent more houses being built to guard the value of their prize possessions, vastly inflated by a combination of lacklustre housebuilding and irresponsible leap in migration. As old people vote and young people don’t — and when they do, vote badly — few sensible people can find a way out of this quagmire.

It might be worth looking to the Mediterranean, where Tal Alster tells us How Israel turned urban homeowners into YIMBYs.

■ It’s disappointingly rare to see intelligent outsiders give a considered impression of the current state of play in the Netherlands — that’s Mother Holland for us New Yorkers. Too often commentators in English are either rash cheerleaders for the hard right or bien-pensant liberals eager to castigate and chastise. Both rush to judgement.

What a rare diversion then to read Christopher Caldwell — the only thinking neo-con? — attempt to explore and explain the success of Geert Wilders in the recent Dutch elections.

■ One in ten of Lusitania’s inhabitants are now immigrants, and this discounts those — many from Brazil and other former parts of the once-world-spanning Portuguese empire — who have managed to acquire citizenship through various routes.

Ukrainian number-plates are now frequently be seen on the roads of Lisbon, as far in Europe as you can get from Big Bad Uncle Vlad.

Vasco Queirós asks: Who is Portugal for?

■ Speaking of world-spanning empires, in true andrewcusackdotcom fashion, we haven’t had enough of the Dutch — but we have had enough of their wicked wayward heresies.

Historian Charles H. Parker explores the legacies of Calvinism in the Dutch empire.

■ The City of New York itself is the best journalism school there is. Jimmy Breslin dropped out of LIU after two years, eventually taking up his pen. Pete Hamill left school at fifteen, apprenticed as a sheet metal worker, and joined the navy.

William Deresiewicz argues that a dose of working-class realism can save journalism from groupthink.

■ The New Yorker tells us how a Manchester barkeep found and saved a lost (ostensible) masterpiece of interwar British literature.

■ Our inestimable friend Dr Harshan Kumarasingham explores David Torrance’s history of the first Labour government on its hundredth anniversary.

■ And finally, one for nous les normandes (ok, ok, celto-normandes): Canada’s National Treasure David Warren briefly muses that the Norman infusion greatly refined Anglo-Saxon to give us the superior English tongue we speak today.

Articles of Note: 29 January 2024

A lively Doubleyoo-Ess once took me to lunch at the New Club and, in whispered tones, pointed out a gentleman sitting at another table.

“He is the world’s leading expert on the Scots tongue,” my friend explained.

“But he was excommunicated by all the other experts on Scots when he pointed out that eighty per cent of Scots words are interchangeable with Northumbrian English.”

Scots is fascinating for its closeness to English and its distinction. Those who’ve had the pleasure of tarrying awhile in the Netherlandic world (whether in Europe, the Cape of Good Hope, or elsewhere) can detect the odd affinities to Dutch and Afrikaans — reminding you that the North Sea was once a highway, not a barrier.

Luka Ivan Jukic has written an enlightening exploration of how and why Scotland lost its tongue.

Jukic contends there are no signs of revival, which I dispute. There is a much increased interest in the use of Scots, but it feels contrived and falls somewhat flat. If you take a look at the Scots column in The National newspaper, it comes across as the ravings of a kook something akin to Anglish.

■ Amongst the many of Scotland’s joys is the pleasure of just looking at its buildings.

Witold Rybczynski pleads “Give us something to look at!” in his account of why ornament matters in architecture.

■ The New York Post — founded by Alexander Hamilton in 1801 and thus the Empire State’s oldest and most venerable newspaper — reports that the world’s oldest and most venerable forest has been discovered right in the heart of the Catskill Mountains.

This is one of the most beautiful places in America, especially when the leaves begin to turn in autumn, and features widely in the old stories transcribed by Washington Irving and others.

The name of the Catskills is believed to be from the catamounts that used to roam the woods and bergs when our Dutch forefathers of old first arrived in the valley of the Hudson. Our earliest record of it is on a map by Nicolaes Visscher père from 1656 — and pleasingly the local magazine retains the old spelling in its name of Kaatskill Life.

This fossilised forest within the Catskills is believed to date from 385 million years ago (for those who doubt the Ussher chronology — and we remain open-minded ourselves) and was discovered at the bottom of an old quarry.

■ As a precocious teenager I remember a visit to the maritime museum in Rochefort on France’s Atlantic coast that included a fascinating display of the intricacies and accomplishments of global shipping, housed in the long old ropeworks that kept France’s navy afloat in the era of sail.

It’s all been kicking off in the Red Sea, which inspired Wessie du Toit to write that the shipping container is an uncanny symbol of modern life

■ Some people claim there is no life outside of NW3, but as much a fan of Hampstead as I am, my first loyalty in London neighbourhoods is firmly lodged in Southwark. (Pimlico is high on the list, too.)

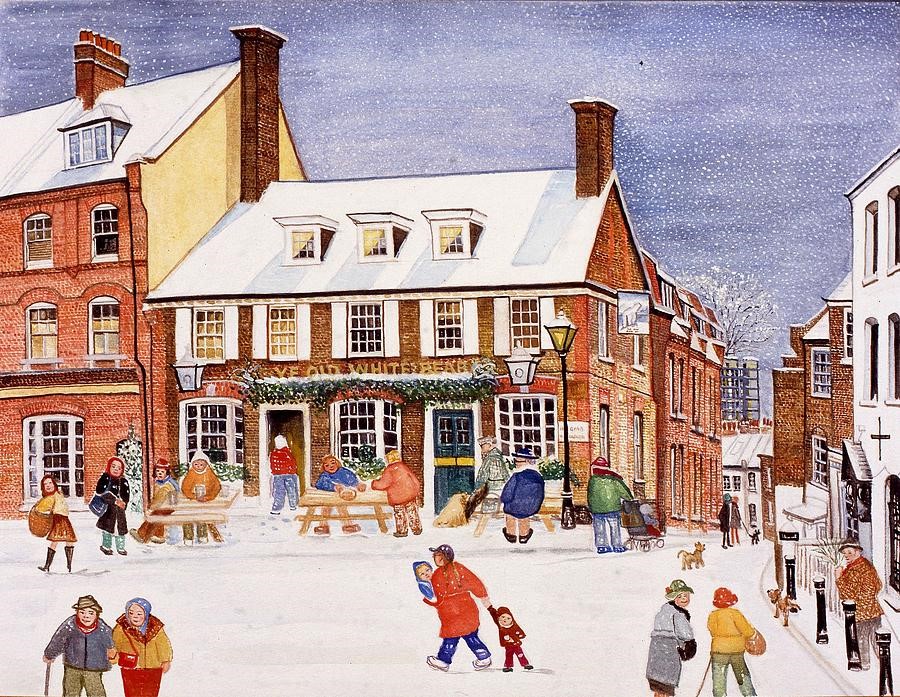

Many will pine for those precious late summer afternoons idly dawdling on the Heath, but Hampstead in winter has its distinct pleasures. For me, it’s curdling up with a pile of books beside the coal fire in the Old White Bear.

In the Christmas issue of The Oldie, Peter York wrote about the rise and fall of arty Hampstead.

■ One of our Hampstead mates is originally a West Country man and now finds himself even further west, studying law in California.

For a New Yorker, California is The Great Other. If not quite a rival, then certainly something we are always being compared against.

Naturally, one looks down on California, but also with a certain envy. If ever America had a golden moment when imperial might was combined with the simple goodness of life, it must have been coastal California from the 1930s to 1960s — with a hint of survival into the 1980s.

California’s decline is evident to all, though its power and influence is still vast (as the iPhone in your pocket proves). The Manhattan Institute recently devoted an entire issue to the question of Can California Be Golden Again?

I haven’t had a chance to read much of it, but I did enjoy Jordan McGillis’s article on how San Diego retains many of the qualities that once made California the envy of the world.

■ Peter Viereck ranks amongst the names of slightly neglected thinkers in the agora of American conservatism. Reading him always brings some insight, but I never knew much about the man himself.

Samuel Rubinstein supplies a fascinating account of the man and his thinking in Peter Viereck: Psychoanalyst of Nazism.

■ National treasure Peter Hitchens has spent his life hating the ogre Ted Heath, destroyer of worlds. I will never forgive him for what he did to England’s ancient counties and boroughs.

But Hitchens the Heath Hater, with his typically thoughtful approach, offers a reconsideration of the man.

■ All politics is local: Fred de Fossard writes about how EU-obsessed Lib Dems are ruining Bath rather than guarding one of the most precious jewels of English cities.

■ We leave you with this six-colour lithograph from the Pretoria-based artist Nina Torr entitled ‘Here we go again’ (an edition of thirty, available from the Artists’ Press):

Articles of Note: 6 January 2024

■ I had the great privilege of studying French Algeria under the knowledgeable and congenial Dr Stephen Tyre of St Andrews University and the country continues to exude an interest. The Algerian detective novelist Yasmina Khadra — nom de plume of the army officer Mohammed Moulessehoul — has attracted notice in Angledom since being translated from the Gallic into our vulgar tongue.

Recently the columnist Matthew Parris visited Algeria for leisurely purposes and reports on the experience.

■ While you’re at the Spectator, of course by now you should have already studied my lament for the excessive strength of widely available beers — provoked by the news that Sam Smith’s Brewery have increased the alcohol level of their trusty and reliable Alpine Lager.

■ This week Elijah Granet of the Legal Style Blog shared this numismatic gem. It makes one realise quite how dull our coin designs are these days. I don’t see why we shouldn’t have an updated version of this for our currently reigning Charles.

■ Meanwhile Chris Akers of Investors Chronicle and the Financial Times has gone on retreat to Scotland’s ancient abbey of Pluscarden and written up the experience for the FT. As he settled into the monastic rhythm, Chris found he was unwinding more than he ever has on any tropical beach.

Pluscarden is Britain’s only monastic community now in its original abbey, the building having been preserved — albeit greatly damaged until it was restarted in 1948. The older Buckfast is also on its original site but was entirely razed by 1800 or so and rebuilt from the 1900s onwards. (Pluscarden also has an excellent monastic shop.)

■ An entirely different and more disappointing form of retreat in Scottish religion is the (Presbyterian) state kirk’s decision to withdraw from tons of their smaller churches. St Monans is one of the mediæval gems of Fife, overlooking the harbour of the eponymous saint’s village since the fourteenth century, and built on the site of an earlier place of worship.

Cllr Sean Dillon pointed out the East Neuk is to lose six churches — some of which have been in the Kirk’s hands since they were confiscated at the Reformation, including St Monans.

John Lloyd, also of the FT, reported on this last summer and spoke to my old church history tutor, the Rev Dr Ian C. Bradley. More on the closures in the Courier and Fife Today.

What a dream it would be for a charitable trust to buy St Monans and to restore it to its appearance circa 1500 or so, available as a place of worship and as a living demonstration of Scotland’s rich and polychromatic culture that was so tragically destroyed in the sixteenth century. You could open with a Carver Mass conducted by Sir James MacMillan.

■ And finally, on the last day of MMXXIII, the architect Conor Lynch reports in from Connemara with this scene of idyllic bliss:

Anglo-Gaullist Reading Update

The latest round of news or commentary of Gaullist content or interest:

Mercator: Charles de Gaulle: a wise ruler of France

Financial Times: France invokes the golden age of de Gaulle

Politico: Why all French politicians are Gaullists

Variety: Cliché-Ridden ‘De Gaulle’ is Unworthy of Its Iconic Subject

Articles of Note: 3.II.2022

“Lebanese money was worth more and there was more to eat when militias were fighting each other in the streets of Beirut 40 years ago than there is today.”

One of the great ironies of Lebanon’s current decline (Fernandez points out) is that, as destructive as the Civil War was, the country’s hopes were finally crushed by bankers and politicians rather than warlords.

— A bumper from The European Conservative: Tim Stanley says “Stay away from politics!” (I couldn’t agree less: we need brighter people involved!)

■ Idealists in Europe refusing to bow to reality have provided false hope to countries that have no real prospect of becoming members of NATO or the EU.

Damir Marusic muses on the Ukraine in How Not to Bend the Arc of History.

■ I ran into my friend João at a dinner party last night and he described the very existence of Brazil as “the greatest thing Portugal ever did”.

In 2018, Americas Quarterly claimed the now-deceased Olavo de Carvalho was the most important voice in Brazil’s then-incoming government (even though he didn’t live there).

More bizarrely fascinating is Nick Burns’s 2019 article on Bruno Tolentino, Carvalho, Ernesto Araújo, and the origins of the new Brazilian right.

Brazil’s foreign minister “penned an eyebrow-raising article for Bloomberg in which he blamed Ludwig Wittgenstein for Brazil’s debility on the world stage”.

If you’ve never lived in Latin America (I claim to have been at least partly educated there) you will never really understand quite how different it is.

■ When Algeria became independent, President Ben Bella had spent so long in French prisons that he had almost forgotten his Arabic.

One million French Algerians left within months, as American diplomats in Paris and Algiers at the time recall.

French Algerians “not only controlled the whole private sector, they had all the top government positions, and more importantly, they filled all the minor positions. The guy who read the gas meter in the utility company was a Frenchman. The women who worked the switchboard in the telephone company were all French. So the economy just came to a screeching halt.”

— Ex Africa semper aliquid novi: A new documentary (watchable online) explores Algeria under Vichy while another looks at Jacques Foccart, de Gaulle’s “Mister Africa”.

■ I am not much of a “Substack” aficionado, but I have recently given in and signed up to receive The Postliberal Order in my inbox. It’s penned by the quadrivirate of Vermeule, Deneen, Pappin, and Pecknold — all of whom have become household names in Cusackistan.

Patrick Deneen’s latest contribution on emerging postliberalism amidst the political persuasions of his students is worth a read.

Fifth Republic Britain

An Anglo-Gaullist Reading Round-up

While I’m a big Adenauer fan there’s little doubt that de Gaulle was the greatest European statesman of the twentieth century and an historical figure of such a position will always be the subject of interest.

Both Jonathan Fenby’s 2010 book The General: Charles de Gaulle and the France He Saved and Dr Sudhir Hazareesingh’s 2012 In the Shadow of the General: Modern France and the Myth of de Gaulle received wide notice, but neither as much as Julian Jackson’s 2019 A Certain Idea of France: The Life of Charles de Gaulle.

Jackson’s work is indeed magisterial and Lord Sumption’s praise of it as “the best biography of de Gaulle in any language” is only just an exaggeration. (For a strong bibliography of works on the general, see the appendix of Charles Williams’s 1993 The Last Great Frenchman: A Life of General de Gaulle.)

Study of the life and contradictions of de Gaulle is always worthwhile, but many spy a Gaullist moment in the Tory party’s refreshingly surprising turn away from ideological liberalism towards a more pragmatic conservatism under Boris Johnson.

Painting Johnson as Britain’s first Gaullist prime minister would be a stretch, but there is certainly some crossover: nationalist, economically interventionist, focused on national sovereignty and national exceptionalism.

■ Eliot Wilson pointed out this summer that Boris has always been difficult to classify in ideological terms.

■ Speccie political editor James Forsyth wrote in The Times that Boris the Gaullist puts action over ideas. Just before the party conference Forsyth also predicted the PM’s speech would be “in line with his recent Gaullist turn”.

■ QMUL’s Nick Barlow explores the parallels between de Gaulle’s Fifth Republic and Boris’s style of government.

■ Meanwhile Aris Roussinos argues that de Gaulle was always right in vetoing British entry into the EEC, and that true-blue FBPE types should welcome Brexit as advancing the cause of European integration.

■ Dean Godson (New Statesman) says that Defence Secretary Ben Wallace is pursuing “almost Gaullist trajectory for future British policy”.

■ When asked (on GB News) where he sits on the political spectrum, national treasure Peter Hitchens expressed his surprise that the Gaullist combination of “strong defence, patriotism, a strong welfare state, and national independence” isn’t more common in British politics.

■ ‘Bagehot’, the political column in The Economist, put it that the man who rebuilt post-war France has some important lessons for Britain’s prime minister: What Boris could learn from de Gaulle.

■ The American Conservative embarrassingly illustrated a piece on Europe’s Gaullist Revival with a picture of General Kœnig. (Always check the képi — as a brigadier general, de Gaulle only had two stars!)

■ Mike Bird discerned some Anglo-Gaullism in a pile of recent newspaper headlines.

■ As long ago as 2017 — what a world away that was! — Prospect argued in a somewhat rambling piece that the Brexiteers were Britain’s new Gaullists.

■ Honourable mention: Frederick Studemann chides Churchill and dumps de Gaulle, saying Boris should model himself on Bismarck and make for a Prussian Brexit.

But, for all this, when New Labour bigwig John McTernan suggested that Boris is not a Churchill but a de Gaulle, the great Julian Jackson himself pointed out there are still great differences between the PM and le général.

All the same, I’m welcoming our Anglo-Gaullist future with open arms.

Articles of Note: 24.II.2021

• It is almost certain that we will never know who the actual winner of the 2020 presidential election was: the methods of fraud which might have been deployed are by their very nature ephemeral. Anton is right in that the best summary of the irregularities is from the U.S.-based Swedish academic Claes Ryn: How the 2020 Election Could Have Been Stolen. Ryn’s academic work is always an insightful read so his take here is worthwhile.

• I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: the Frenchman Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is always worth reading and always brings something to the table. P.E.G. argues the pre-Trumpers, anti-Trumpers, and never-Trumpers on the American centre-right need to recognise the reasons why Trump became a political phenomenon in the first place: Why Establishment Conservatives Still Miss the Point of Trump.

• One of the best books on urbanism in the Cusackian library is Allan Jacobs’s Great Streets. The expert work with its illustrative maps, diagrams, and line drawings is now a quarter-century old and on this anniversary Theo Mackey Pollack examines What Makes a Great Street.

• A new book argues that our vision of Northern Ireland as a corrupt and gerrymandered statelet from its birth in 1921 until the imposition of direct rule in 1972 is largely a myth. The editors Patrick J Roche and Brian Barton take to the pages of the once-great Irish Times to offer A Unionist History of Northern Ireland. It’s… an interesting perspective that will doubtless provoke a debate, but colour me sceptical.

Articles of Note: 15.I.2021

• Autumn and winter are a time for ghouls and ghosts and eery tales. At Boodle’s for dinner two or three years ago I sat next to the wife of a friend and exchanged favourite writers. I gave her the ‘Transylvanian Tolstoy’ Miklos Banffy, in exchange for which she introduced me to the English writer M.R. James — whose work I’ve immensely enjoyed diving into. The inestimable Niall Gooch writes about Christmas, Ghosts, and M.R. James, as well as pointing to Aris Roussinos on how Britons’ love for ghostly tales is a sign of (little-c) conservatism.

• There can be few figures in English history more ridiculous than Sir Oswald Mosley. But the Conservative MP who became a Labour government minister and then British fascist führer-in-waiting was also forceful in his condemnation of the savagery unleashed by the Black-and-Tans. In 1952 a local newspaper in Ireland announced that Sir Oswald and Lady Mosley “charmed with Ireland, its people, the tempo of its life, and its scenery” had taken up residence at Clonfert Palace in Co. Galway. “Sir Oswald,” the paper noted with amazing restraint, “was the former leader of a political movement in England.” Maurice Walsh presents us with the history of Mosley in Ireland.

• The death of the late Lord Sacks, Britain’s former Chief Rabbi, was the subject of much lament. Rabbi Sacks was obviously no Catholic, but his intellect, frankness, and generosity were much appreciated by Christians. Sohrab Ahmari, one of the editors at New York’s most ancient and venerable daily newspaper, offers a Catholic tribute to Jonathan Sacks.

• “Education, Education, Education” has become a mantra in the past quarter-century and while there is a point there’s also a certain error of mistaking the means to an end for the end itself. After all, in the 1930s Germany was the most and highest educated country in the world. At Tablet, probably America’s best Jewish magazine, Ashley K. Fernandes explores why so many doctors became Nazis.

• Fifty years ago the great people of the state of New York rejected both the Republican incumbent and a Democratic challenger to elect the third-party Conservative candidate James Buckley as the Empire State’s senator in Washington. At National Review Jack Fowler tells the gleeful story of the unique circumstances that brought about this victory for Knickerbocker Toryism and how Mr Buckley went to the Senate.

Articles of Note: 23.XI.2020

• France’s Year of de Gaulle has marked the fiftieth anniversary of his death earlier this month and what would have been the general’s one-hundred-and-thirtieth birthday yesterday. Julien Nourian has put together a Weberian analysis of the general and his charismatic mystique.

• President Trump is a very different kind of leader to de Gaulle, and his chances of continuing in the White House are not looking great at the moment. (Our head of legal in New York thinks he’s still got a chance, however.)

Regardless of who will be inaugurated in January of next year, Trump managed to win the highest proportion of minority votes of any Republican candidate since 1960 (when the GOP choice was a member of the NAACP). Meanwhile, Trump lost votes among old, white, well-to-do men.

What is the future of American political conservatism? Ben Hachten points out It’s Not Your Father’s GOP.

New England poli-sci professor Darel E. Paul explores The Future of Conservative Populism, pointing out the big increase in the Hispanic vote for Trump — especially Hispanics living in Texas along the Mexican border.

• In Britain, Ferdie Rous says the Conservative party is having difficulty reconciling the business wing of the party with our rural roots, but suggests that The writings of Lewis and Tolkien embody conservative environmentalism.

Meanwhile David Skelton asserts It was working class voters who delivered this majority – and Johnson must not abandon them now.

• Here in London we’re still in the middle of the second lockdown. Instead of following the science, governments around the world are implementing the exact opposite of effective measures to combat the pandemic. It’s The Greatest Scandal of Our Lifetime according to R.J. Quinn.

• We can always do a with a dose of Metternich and Wolfram Siemann’s 900-page doorstop has provided a chance for many to analyse the master diplomat. Ferdinand Mount examines The Prime Minister of the World.

• And finally, the Museum of Literature Ireland features an online exhibition on the American writer, speaker, reformer, and statesman Frederick Douglass’s visit to Ireland 175 years ago. (Available as Gaeilge too.)

Articles of Note: 5.II.2020

• Some enthusiasts like to go bird-watching, but James Panero of The New Criterion likes to go house-watching. “[O]ur country is fertile ground for good house-watching. Fine examples, of just about any style of any period, abound. What stories they tell if only we listened to their calls.”

• Psephologists are still extrapolating ideas and conclusions from the results of December’s general election here in the UK that handed Boris Johnson a handy majority. One of the most important analyses comes from the philosopher John Gray in the New Statesman: Why the Left Keeps Losing.

• For years, EU leaders have insisted that Brexit would be a disaster for Britain, leaving your country hopelessly isolated, Alexander von Schoenburg, the editor of Europe’s highest-selling newspaper, reports from Berlin. “According to the relentless propaganda of the pro-EU cause, Europe would forge ahead on the global stage, ever more united, while the UK would slide into insularity and decline. But that narrative is starting to look like a delusion.”

• British liberals have created a Europe of their imagination, Ed West writes at UnHerd. But how closely does it resemble reality?

• As the founder of the Anglo-Gaullist Working Group I often ask myself “What would de Gaulle do?” James Pinkerton (the American Conservative) argues that when it comes to Afghanistan, the great Frenchman would advise President Trump to stand his Deep State antagonists down and bring the troops home.

• For centuries Spain faced a perfect storm of enemies that fostered an anti-historical legacy of lies collectively known as the Black Legend. In the University Bookman, Alberto M. Fernandez reviews the surprise Spanish best-seller written by a woman who, according to one newspaper, “has liberated thousands of ideological hostages from a national cancer”.

Articles of Note: 11.XII.2019

• The 1930s Oxford social anthropologist J.D. Unwin studied five thousand years of human existence and discovered you can either have a high level of cultural achievement or widespread sexual freedom but never both. Kirk Durston explores why sexual morality may be far more important than you ever thought.

• America’s secular liberalism isn’t secular at all: it is merely the latest stage in the adaptation of an inevitably deracinated Protestantism, Patrick Deneen argues.

• René Rémond’s model of France’s three right wings — Legitimist, Bonapartist, and Orleanist — is breaking down because, Luke Nicastro argues, Emmanuel Macron is co-opting both Orleanists and Gaullists into his electoral family.

• And finally, a historic note, it’s been more than a quarter-century since the late Anthony Lejeune went on A Tour of New York’s Clubland.

Articles of Note: 22.XI.2019

• In Spiked, James Heartfield urges us to spurn Labour’s counsel and instead stop apologising for the past.

• Michael Brendan Dougherty in National Review wonders if Republican Missouri senator Josh Hawley might be the next Daniel Patrick Moynihan.

• Why would an Eton- and Oxford-educated man assert he ‘supports’ Aston Villa, a football team based in a slum in Birmingham, a city with which he has no connection? Theodore Dalrymple ponders David Cameron’s Big Lie at Law & Liberty.

• At the American Conservative, Rod Dreher ponders the radicalism of today’s left and whether its religious fervour to deny scientific realities like biological sex is driving Trump-hating lefties to back the Donald for president.

• And, for a decent long read, politics professor Daniel E. Burns examines how critics and defenders of liberalism often argue past one another:

It refers, on the one hand, to a set of political practices, and on the other hand, to a political theory that purports to explain those practices. Defenders of liberalism are thinking first and foremost about liberal political practice, which they (almost all) defend by drawing selectively on liberal theory. Critics of liberalism are thinking first and foremost about liberal political theory, which they (almost all) attack by pointing selectively to liberal practice.

In National Affairs, it’s a question of Liberal Practice v. Liberal Theory.

Around

“By contrast, Hungary’s 100,000 Jews—a larger presence relative to the country’s population of 8 million—walk unmolested to synagogue in traditional Jewish costume and hold street fairs with minimal security presence.” The Real Modern Anti-Semitism

No American writer has wielded such influence, John Rossi writes. So why is he so little known today? The Strange Death of H.L. Mencken

Damon Searl on Uwe Johnson: The Hardest Book I’ve Ever Translated.

Then there are the mythical and miraculous islands of the medieval Atlantic

120 years after the Spanish-American War, here are five books to help you better understand American imperialism.

The always-worth-reading Michael Brendan Dougherty explores what the Catholic traditionalists of the 1960s and 1970s were thinking. (More people, however, are talking about his look at Francis’s record as pope.)

In Manhattan, John Massengale suggests there are better ways to get around town.

Argentina’s most beloved bibliophile Alberto Manguel on the great books that are now lost to history.

In Hungary, like everywhere else, people are marrying later, with demographic consequences. Or is this changing? The country is not just experiencing a fertility spike, Lyman Stone reports. Hungary is winding back the clock on much of the fertility and family-structure transition that demographers have long considered inevitable. Is Hungary Experiencing a Policy-Induced Baby Boom?

Speaking of which, from the same author, what about Poland’s Baby Bump?

Meanwhile in New England, an entitled Harvard academic pulls rank on the mother and child living in an affordable unit in their apartment building in a telling tale of class and hierarchy in America.

The Epiphany 6 January 2016

Architectural historian Gavin Stamp argues that if Rhodes really was such a vicious baddie as his opponents claim, why stop with just removing his statue?

South African academic and Rhodes scholar R. W. Johnson has compared the campaign to remove Rhodes statues to ISIL’s destruction of antiquities in the Middle East while clerical commentator Fr Alexander Lucie-Smith recalls the damnatio memoriae.

Most interesting perhaps is the treatment of Rhodes not in the ivory towers of Oxford or Cape Town but in the land that once bore his name. Rhodes’s grave still lies in a prominent spot in the Motopos, but even President Robert Mugabe is against exhuming him.

From the Telegraph:

The last time that a call was made for the grave in the Matopos to be exhumed, Middleton Nyoni, then Town Clerk of Bulawayo, offered a telling response. “It is the Taliban who destroy history – and I am not a Taliban,” he declared. “After Rhodes’s grave, who is next?”

When Rhodesia became Zimbabwe in 1980, the city fathers of Bulawayo shifted Rhodes’s statue from the town centre to the town museum, while covering up the plaque commemorating his indaba with the chiefs of the Matabele. But in 2010 the city council voted to uncover the plaque while last year the Zimbabwean playwright Cont Mhlanga provocatively suggested returning Bulawayo’s statue of Rhodes to its former place of prominence.

U.C.T. has dumped Rhodes – though he remains elsewhere on Table Mountain – and his statue is still at Oriel… for now.

– This time last year, Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry asked if the Christian revival was starting in France. My pilgrimage to Chartres provided me with evidence that the faith across the Channel is deep, strong, and growing.

Now, looking forward to the year ahead, P.E.G. notes that Catholic France used to be old and rural — now it is young and urban: “In the major cities, all the churches are full on Sunday morning, something unthinkable even 10 years ago.”

– Former CIA agent Philip Giraldi visits Russia for the first time.

— All across the world, evidence shows that poverty is dropping dramatically. Why then, Fraser Nelson asks, is it so hard to believe?

Bicycle polo at the Wellington Monument in the Phoenix Park, 1938.

What You Should Read

Three recommendations and some honourable mentions

Over at ISI’s Intercollegiate Review, there’s a post by Joseph Cunningham suggesting eight publications you should be reading. In September I came up with a handful of suggestions of what blogs or websites readers ought to take note of, particularly if they exist in the Catholic/traditionalist/conservative realm so difficult to sum up in a single word or term.

Of course, most of what you should be reading is by dead people (suggestions of who I proffered herein, including some actually alive), but while Chesterton described tradition as the democracy of the dead we would be remiss to carry forth in ignorance of the living.

Publications wise, then, what is the well-read gent, or lady, reading? I’ve judged this question by what I’ve managed to persuade/force/intimidate my friends into subscribing to or buying, as well as by my own habits.

This fortnightly review is one of the last places where long-form essays are still the norm. One of the adventures of starting to read a piece in the LRB is that one has no idea whether it will continue for two of the Review’s large pages, or six, or maybe more. In addition to intellectual essays it also contains occasional reporting from Patrick Cockburn, arguably the best journalist reporting on the Middle East today. (You can read my review of Cockburn’s latest book over at Quadrapheme.)

Is it left-wing? Unquestionably. But if you’re only reading what you already agree with, you’re missing the point. Your principles should be strong enough to face challenges, or to be informed by them, and the ability to separate the wheat from the chaff is the most necessary task for any thinking person.

This American monthly came in for a lot of flak from a lot of conservative intellectuals for propagating and defending the neo-con support for the Iraq War, but the Daily Telegraph’s description of The New Criterion as ‘America’s leading review of the arts and intellectual life’ remains true to this day. (Disclosure: I was an editor at TNC from 2006-2008.) Feature articles are informative and expanding, the book reviews provide a good guide for reading, and art-wise I’ve always admired the clean prose of James Panero’s Gallery chronicle.

In recent months New Criterion readers have had the privilege of learning about the Jesuit linguist Albert Jamme’s hatred for sleep — “I hate my bed because it keeps me from my texts!” — and a Duke of Mantua’s expensive interest in female dwarves while last year they published the Quaker pacifist classical scholar Sarah Ruden on the darker side of Mandela’s government. Worth reading every month.

Founded in 1957 by Russell Kirk — the greatest St Andrean of the twentieth century — Modern Age is an academic journal which Wikipedia describes as ‘traditionalist, localist, against most military interventions,’ as well as critical of neo-conservatism and generally sympathetic to religious orthodoxy.

Its archive over the past sixty years provides articles and essays of great value by Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn, Virgil Nemoianu, Lee Congdon, Pierre Manent, and others. Take, for example, Lee Congdon on ‘Conservatism, Christianity, and the Revitalization of Europe’.

A rewarding, more scholarly read, with footnotes that will lead you elsewhere.

These three will prove worthwhile reading for any intellectual of sound principles, but are there any other honourable mentions?

My weekly workplace reads are The Spectator and The Economist which are useful for keeping tabs on things in general.

I have to admit I do read Monocle every month. While it’s aimed at wealthy jetsetters rather than our own constituency of cosmopolitan conservatives living in genteel poverty the magazine nonetheless combines an exacting stylistic excellence with an admirably broad focus.

First Things I would read every month but it doesn’t seem to be available anywhere in London except by subscription.

Two or three times a year I pick up The Art Newspaper, another superbly put-together periodical. Fr Christopher Colven of St James, Spanish Place, writes for it often, as it happens.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Articles of Note: 27 January 2025 January 27, 2025

- Spooks’ Crown January 23, 2025

- Jesuit Gothic January 23, 2025

- Christ Church December 29, 2024

- A Christmas Gift from the Governor December 24, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories