India

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Rashtrapati Bhavan

Debates rage in the trad community as to whether, in the context of India, it is more sound to support the Congress Party or to take some relief in the policies of Mr Modi and his Indian People’s Party (curiously always known in English as the BJP).

Presented with the choice of left-leaning instability with Congress or Hindutva-oriented instability with the BJP, one recalls Hofrat Kissinger’s comment about the Iran-Iraq War: “Isn’t it a shame they can’t both lose?”

But the recent visit to India of my fellow New Yorker, His Excellency the President of the United States, necessitated his calling in to one of the grandest residences of any head of state the world over: Rashtrapati Bhavan, the residence of the President of India.

Originally called Viceroy’s House, it was designed by Lutyens as the palace of one of the most powerful men on the face of the planet: the Viceroy of India.

But the building of this magnificent structure was an imperial swansong. Opened in 1931, just sixteen years later the subcontinent was partitioned, the Indian Empire and its Viceroy abolished. The Union of India took its place, with a Governor General instead of a Viceroy.

In 1950, this too was abolished as the Union became a republic, and the office of governor general was given a republican whitewash and renamed as President of India.

This head of state is not elected by the voters of the world’s largest democracy except indirectly through a combined college of the national parliament and the state legislative assemblies. Like a governor general, he does have some power but the real force lies in the prime minister — today Mr Modi.

Nevertheless, this building reflects the glory, power, and influence of one of the greatest nations of the earth.

Gandhi in Fascist Rome

Returning home to India from the second London Round Table Conference in 1931, the genial Indian nationalist leader Mr Gandhi decided to call in on that most ancient, venerable, and eternal city of Rome. He accepted the invitation to stay as a guest of the aviation pioneer (and later fascist senator) General Maurizio Moris and, purporting to be of something of a spiritual aficianado, hoped to be granted an audience with the Holy Father. Gandhi had by then adopted an unwavering costume of sandals and homespun which was thought unsuitable for the papal court, and Pius XI — in many ways a wise man — decided against the Indian’s request. Mussolini, however, was less fussy and granted the “Mahatma” a private audience on the very evening of his arrival.

In some ways they were similar: Gandhi and Mussolini shared a gift for the theatrical as well as an unshakeable self-belief. Mussolini fancied himself the leader of his people, despite the King above him, and Gandhi thought likewise of himself despite the entire apparatus of the Raj standing apart from and above him. Gandhi, however, never stooped to the level of the buffoon, unlike his Italian friend, and (even after independence) wisely abjured himself from ever taking on the actual responsibilities of government and state office. (more…)

An Organic Simplicity in School Design

Shriram Junior High School, Mawana, India

Deependra Prashad, the chairman of the Indian branch of the International Network for Traditional Building, Architecture, and Urbanism (INTBAU) has won the Indian Building Congress Award for Excellence in the Built Environment for his design of the Shriram Junior High School in Mawana, U.P. The small primary school was commissioned by the sugar company which owns the industrial campus on which the school sits. Managers were concerned that workers were sending their children to schools further away from the site, and so began a non-profit school arm to breathe new life into the old school. This included a new building designed by Deependra Prashad. (more…)

The Khan Market

“One of the happier moments in what has begun to feel like a long life (for I have now lived through three dekaenneateric cycles), was in the Khan Market at New Delhi,” writes the columnist David Warren.

This was some time ago. There was a bookstore in that market (perhaps there still?) and I am happy as a simile in a bookstore. It was before the Indian economy had turned, in merry cartwheels of Vedic Thatcherism — before the Khan Market had become one of the world’s most expensive retail locations. In those days it was merely well-appointed, and (for India) almost provocatively clean.

It was something about the condition of the light, and the cool air (a late winter afternoon); the understated display of all goods; the polite modesty of both salesmen and customers; the gorgeousness of Delhi ladies in their saris. I felt for a moment that I was in Utopia, and that this was its corner market.

The Oriental Club

Stratford House, London

JUST STEPS AWAY  from Oxford Street, one of London’s busiest thoroughfares, rests a quiet little street called Stratford Place probably familiar only to Tanganyikans or Batswana seeking counsel from their countries’ high commissions. At the termination of the dead-end street sit the stately quarters of the Oriental Club: Stratford House. The club was founded in 1824, as British involvement and influence in both India and the Orient was waxing rapidly. General Sir John Malcolm, sometime Ambassador of His Britannic Majesty to the Court of the Peacock Throne (which is to say, Persia), coordinated the founding committee and advertised a club which would draw its members from “noblemen and gentlemen associated with the administration of our Eastern empire, or who have travelled or resided in Asia, at St. Helena, in Egypt, at the Cape of Good Hope, the Mauritius, or at Constantinople.” (more…)

from Oxford Street, one of London’s busiest thoroughfares, rests a quiet little street called Stratford Place probably familiar only to Tanganyikans or Batswana seeking counsel from their countries’ high commissions. At the termination of the dead-end street sit the stately quarters of the Oriental Club: Stratford House. The club was founded in 1824, as British involvement and influence in both India and the Orient was waxing rapidly. General Sir John Malcolm, sometime Ambassador of His Britannic Majesty to the Court of the Peacock Throne (which is to say, Persia), coordinated the founding committee and advertised a club which would draw its members from “noblemen and gentlemen associated with the administration of our Eastern empire, or who have travelled or resided in Asia, at St. Helena, in Egypt, at the Cape of Good Hope, the Mauritius, or at Constantinople.” (more…)

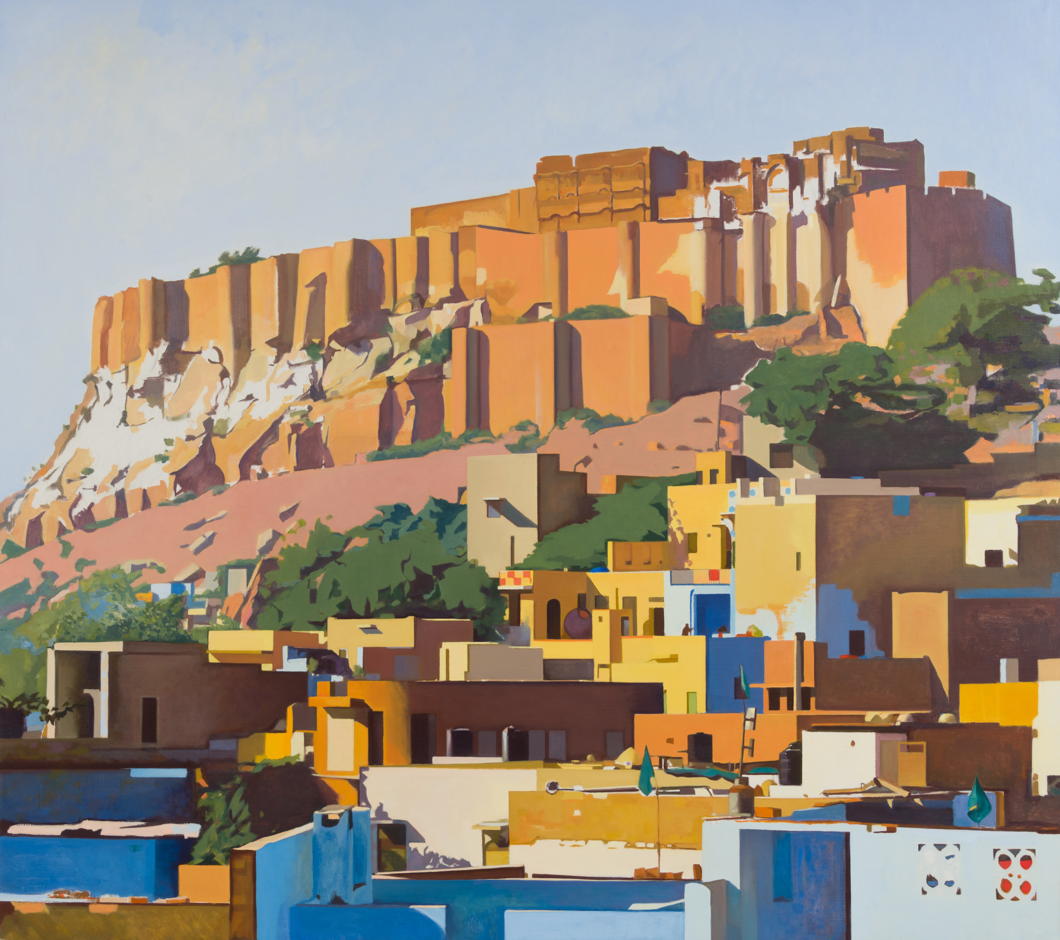

Alexander McCall Smith & the Sisters of Jaipur

The Scottish writer Alexander McCall Smith — noted for the fact that his books are actually a pleasure to read — pens a letter to readers every few months. In the latest letter, he mentions that he recently attended the Jaipur Literary Festival in Rajasthan’s famous “Pink City”:

But the visit to Jaipur was not all literary festival. My wife and I paid a visit to the Mother Theresa Home in the city, which was, as you can imagine, a very moving experience. Over two hundred residents, most of them with nowhere else to go, no possessions, and no money, are looked after by some seven sisters. These sisters are tireless – completely tireless – and give their lives over to the living care of these abandoned people.

At a time when the Catholic Church is coming under severe criticism for its failures (which have been, understandably, very much in the news), we should perhaps remember the extraordinary work of people such as the nuns of this community, who have done so much to bring love into the lives of those who have nothing and who would otherwise die alone and uncared for. I cannot tell you how moved I was by what I saw and by my conversation with the nuns.

An apposite reminder.

If you haven’t yet read Prof. McCall Smith’s 44 Scotland Street series, I suggest you float down to your nearest bookseller and purchase the first installation (handily titled 44 Scotland Street) today. They are a procession of delightful stories surrounding a number of fictional characters in an Edinburgh townhouse, and if you’re familiar with the capital city, you might just come a cross the occasional non-fictional friend interspersed amongst the creations of McCall Smith’s mind.

H.H. the Maharaja of Patiala

Lieutenant-General His Highness Farzand-i-Khas-i-Daulat-i-Inglishia, Mansur-i-Zaman, Amir ul-Umara, Maharajadhiraja Raj Rajeshwar, 108 Sri Maharaja-i-Rajgan, Maharaja Sir Bhupinder Singh, Mahendra Bahadur, Yadu Vansha Vatans Bhatti Kul Bushan, Maharaja of Patiala, Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of India, Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire, Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order, Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire, Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St. Gregory the Great, Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Dannebrog, Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer, Grand Cross of the Order of Charles III, Grand Cross of the Legion d’Honneur, Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Sts. Maurice & Lazarus, Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown of Italy, Grand Cross of the Order of the White Lion, Grand Cordon of the Order of the Nile, Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold, ascended to the throne of Patiala in 1900. A keen cricketer, the Maharaja captained the 1911 Indian cricket tour of England, and played in twenty-seven games of cricket at first-class level between 1915 and 1937. Indeed, for the 1926-27 season he played for the MCC itself. (more…)

Rabbiting on…

Readers might be interested in a new blog called Rabbiting On, by one V. Narayan Swami from Madras in the ancient land of India. Incidentally, the city council of Madras (known as the Chennai Corporation) is reputed to be the oldest municipal body in the Commonwealth of Nations outside the British Isles, its charter being granted by King James II (c.f. here & here) in 1687. The governor of Madras at that time was one Elihu Yale, who was subsequently removed in a corruption scandal and later became the patron of an academy in Connecticut which know proudly bears his name.

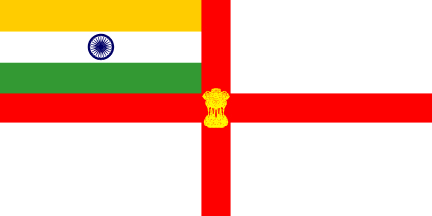

St. George Guards India’s Fleet Once More

In a return to tradition, the old Indian naval ensign is reinstated.

AFTER AN EXPERIMENT with an allegedly more ‘indigenous’ design, India’s traditional naval ensign has been restored, and so the Cross of St George once again snaps from the sterns of the Union’s warships. The old Indian Naval Ensign dated to 1950, when the Indian Union became a republic, three years after achieving dominion status as a wholly self-governing member of the British Commonwealth. The Royal Indian Navy had flown the unaltered White Ensign but with the changeover to a republic it was decided to simply exchange the Union jack in the canton with the national flag of India, retaining the red St. George’s cross on a white field. (more…)

Queens College

Queens College in Benares, India. Has a rather haunted feel to it in this photo.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Waarburg October 2, 2024

- A Prize for the General September 23, 2024

- Articles of Note: 17 September 2024 September 17, 2024

- Equality September 16, 2024

- Rough Notes of Kinderhook September 13, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories