Great Britain

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Return of the Warner!

Gerald Warner of Craigenmaddie, one of Britain’s greatest living journalists, now has a splendid blog over at the Daily Telegraph called Is It Just Me? I am sure you will all want to take a look at it. Already he has an appreciation of the recently deceased Franz Künstler, until his death the last living soldier of the Hapsburg army, a brief missive pointing out how terribly un-British the idea of a “Britishness Day” is, and a forthright post on the value of the stiff upper lip in times of crisis.

Gerald Warner of Craigenmaddie, one of Britain’s greatest living journalists, now has a splendid blog over at the Daily Telegraph called Is It Just Me? I am sure you will all want to take a look at it. Already he has an appreciation of the recently deceased Franz Künstler, until his death the last living soldier of the Hapsburg army, a brief missive pointing out how terribly un-British the idea of a “Britishness Day” is, and a forthright post on the value of the stiff upper lip in times of crisis.

Much of what Gerald says is, to sensible people, simply obvious. But one of the great dangers of our modern age is that what ought to be simply obvious is becoming less and less so due to deliberate obfuscation by the political and media classes. Gerald’s talent is that he tells you what’s what and that he manages to do it with a graceful alacrity, and often wit, that are a welcome — and, sadly, rare — treat. Go, read, enjoy!

Warneriana: Gerald Warner Axed | ‘The Mass of All Time answers that need’ | Martyrs of Spain, Pray for Us! | Warner on the Gotha

The Crown of Disenchantment

Over in Great Britain, the House of Commons recently passed the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Bill which, among other things, keeps the time limit on abortions at twenty-four weeks (in spite a hope that it would be lowered), authorizes the creation of “savior siblings (brothers and sisters deliberately created in a lab solely for their organs to be harvested for use by the already-born), and allows for the creation of animal-human hybrids. The British human rights activist James Mawdsley, famously jailed for over a year by the military junta in Burma, has asked opponents of the HFE Bill to sign a petition to Queen Elizabeth II imploring her to withhold the royal assent necessary for the Bill to become law.

Under the British constitution, a bill only becomes a law when it has received the assent of all three components of the British Parliament: the Commons, the Lords, and the Crown. The last time the Crown withheld consent was in 1708 when Queen Anne refused to sign the Scottish Militia Bill. Since that time, it has been an unspoken convention that should the Crown object to a piece of legislation, it should privately inform its ministers before the legislation is voted upon in order for it to be withdrawn, thus preventing the scandal of the Crown and the Commons appearing to be in disagreement. Despite this convention, however, the Crown still has the right to withhold consent, but merely neglects to exercise that right.

While the Crown has faded to near-irrelevance in the everyday workings of the British government, this was certainly not always the case, and the Crown has intervened in politics several times since Queen Anne’s refusal of assent in 1708. What follows are but a few twentieth-century examples.

In 1925, William Mackenzie King was Prime Minister of Canada with 99 Liberal MPs to the Conservative opposition’s 116. He was able to do this by forming a minority government with the support of the 24 MPs of the Progressive Party. A year later, Liberal MPs were implicated in a bribery scandal and so the Progressives having withdrawn their support for the minority government. As parliament debated a motion to censure the MPs involved, the Prime Minister asked Lord Byng, the Governor-General of Canada (and thus the direct representative of the Crown), to dissolve parliament and call a general election.

Lord Byng did not want it to appear that the Crown was allowing parliament to be dissolved in order to prevent the censure of government MPs and so used the royal prerogative and refused to call an election. The Conservatives, as the largest party in parliament (Lord Byng argued), should have a chance at forming a government instead. The Governor-General invited Arthur Meighen, leader of the Conservatives, to form a government instead, and Meighen agreed. This, in turn, infuriated not only the Liberals but also the Progressives, throwing the middle-man back into the Liberal camp. Meighen put his government up to a vote of confidence, lost it by one vote, and so resigned and asked the Governor-General to dissolve parliament and call an election, which Lord Byng duly did.

“I have to await the verdict of history to prove my having adopted a wrong course,” Lord Byng wrote, “and this I do with an easy conscience that, right or wrong, I have acted in the interests of Canada and implicated no one else in my decision.”

In 1931, when the Labour Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald submitted his resignation to the King, George V took the unprecedented step of asking MacDonald to form a national government with the support of Conservatives and Liberal Members of Parliament. MacDonald lasted as Prime Minister until 1935, but Great Britain would not be governed by a single-party government again until 1945.

More recently, the Crown controversially intervened in Australian politics in 1975. Gough Whitlam’s Labor government commanded a majority in the House of Representatives but the opposition coalition of the Liberals and the National Country Party held sway in the Senate. It is traditional in Westminster-style systems that if a money supply bill fails to pass, the government falls with it. The Senate refused to vote on the annual Budget, in hopes of provoking Whitlam into calling a new election. Whitlam stubbornly refused, and the impasse grew as the weeks passed and, with no budget approved, it looked like the government of Australia would not be able to meet its financial obligations for the year.

Finally, the Governor-General of Australia, Sir John Kerr, used the royal prerogative to dismiss Whitlam as Prime Minister, asked the opposition leader Malcolm Fraser to take the job. Fraser formed a caretaker government solely to pass the appropriations bill then immediately called a new election which his own Liberal/National Country coalition won handily.

Such royal interventions, however, are not limited to the English-speaking world. Belgium’s King Baudouin I, a Charismatic Catholic and friend of Francisco Franco, famously refused to give assent to a bill liberalizing the kingdom’s abortion laws. The Prime Minister, Wilfred Martens, simply had the King declared temporarily unable to reign and the Government signed the Bill in place of the King (as is provided in the Belgian Constitution). Two days later, the Government declared the King able to reign once more, and all was back to normal (except for the unborn children killed thereafter, of course).

One of the great benefits of a monarchy is this: that the Crown act as a source of authority, free from democratic accountability, who is capable of blocking any egregious acts which the government of the day may attempt. The HFE Bill is the perfect example of a bill the Crown ought to reject, for the benefit of all the kingdom, most especially the unborn. Yet we can reasonably assume that Elizabeth II will grant her assent to this travesty of law nonetheless, as the current occupant of the throne has (ironically) so thoroughly and woefully imbibed the democratic spirit that she knows not how to fulfill her purpose and duty as Queen. (It is important to note that in neither the King-Byng affair nor the Whitlam-Kerr affair was the Governor General acting on the orders of the actual person who was the Crown at the time, but rather on their dutiful instinct as the local incarnation thereof). It is disappointing to those who are unflinching in their attempts to defend the British Monarchy that the British Monarchy insists on participating in, and sometimes urging on, the very sort of wickedness which we look to the Crown to protect us from. Alas, so far we have looked in vain.

Which Scots conservatism?

FOR THOSE WHO haven’t been keeping up with Caledonian affairs, Scottish independence has been brought onto the agenda by the victory of the anti-unionist, pro-independence Scottish National Party in the general election for the Scottish Parliament last year. The SNP victory comes after about half a century of solid domination of Scottish politics by the Labour party (now in regional opposition in Edinburgh, but still in power at the British parliament in Westminster). Yet an important portion of the electorate, while willing to vote the SNP into power — or at least to vote Scottish Labour out of power — have proved more reticent when it comes to the actual matter of ending the 300-year union between England and Scotland. While the SNP is riding high in Holyrood (the seat of the Scottish Parliament), support for Scottish independence is at its lowest since the discovery of North Sea oil.

This may seem like something of a contradiction, but Scottish voters are just trying to make the best of a tricky situation. Labour have proved unpopular both for national reasons (the war in Iraq particularly and Tony Blair in general) and for local reasons (Scottish Labour’s mismanagement during ten years in power at Holyrood and the presumption the Labour clique have that they are Scotland’s natural rulers and how dare anyone think otherwise). Of the five parties in the Scottish Parliament, the Nationalists are the only purely Scottish party — with Labour, the Conservatives, the Liberal Democrats, and the Greens all having either superior (or in the Greens’ case, co-equal) bodies in London. The best way of kicking out Labour was to vote SNP, and enough Scots thought it was worthwhile this time around.

That the Nationalists are a broad-based party has proved a great advantage. Beyond the central issue of their proposal to make Scotland independent, the SNP’s policies are, roughly-speaking, pro-business center-left. At the same time, their student federation is officially socialist, and they receive a fair amount of conservative support because conservatives tend to of a somewhat nationalist strain — and because the Scottish Conservatives give the appearance that they are more than comfortable to simply sit in Holyrood, collect their parliamentary salaries, and twiddle their thumbs. The Conservatives have always been a London-centric party anyhow, and under David Cameron it has become even more clear that it is a rural conservative party which exists in the hope of placing respectable metropolitan liberals in power. Faced with the choice of three liberal parties — the SNP, the Lib Dems, and the Conservatives — and pseudo-socialist Labour, Scots have made a sensible decision by choosing the liberal party which cares most for Scotland: the Nationalists.

But what, again, of this divergence: a party in government for which independence is its foremost purpose and a people who still seem content on (in some shape or form) maintaining the Union? Some in the opposition parties have seen an opportunity in this contradiction and have called for a referendum on independence to be held now; independence would almost (but only almost) certainly be defeated. Wendy Alexander, the Scottish Labour leader, surprisingly lent her support this idea before being forced by her superiors in London to issue a “clarification” opposing the idea. Those who support the continued union between Scotland and England, Wales & Northern Ireland would be wise to push for a referendum at the nearest moment and pull the rug from beneath the independence lobby.

But is the Union worth preserving? Ought conservative Scots to support the continuation of the Union or a move to independence? A unionist conservative might claim that by our very nature as conservatives we ought to support the status-quo and be wary of such far-reaching radical ideas such as ending three centuries of union. To which, of course, the nationalist conservative replies by asking why Scotland should be ruled by a London-based government intent on social and cultural revolution and the overthrow of all tradition. To which the unionist conservative replies that an independent Scottish government is just as likely to be the enemy of all that is good and holy as the London government. And so on and so forth.

Right-thinking Scots who condescend to involve themselves in politics are currently divided between two political parties — the Scottish Nationalists and the Scottish Conservatives — and that this hampers the cause of tradition, order, and liberty in Scotland.

What, then, should be done? The Scottish Conservative party is an inherently flawed vehicle for the advancement of conservatism in Scotland. The party itself only dates to 1965; before then there was a loose association of unionist elected officials who ran under various banners — Liberal Unionist, Scottish Unionist, Progressive, Independent, National Liberal, etc. It was only in that year that the Scottish Unionist Association decided to become the Scottish Conservative & Unionist Party, the official Scottish branch of the (traditionally English) Conservative & Unionist party. The fortunes of the Scottish Conservatives have gone downhill ever since, and there is a very strong cultural bias (sometimes even hatred) of “the Tories” in general that hurts the Scottish party.

There are two main options at hand. The first is that the Scottish Conservatives completely divorce themselves from the English & Welsh party, undergo a complete “re-branding” and transformation. The Conservative name will have to be dumped and there must be a clear indication that the party’s officials are willing to put Scotland’s interest first and foremost both at Westminster and in Holyrood. The disadvantage is that any new identity will still be tarred with the Tory brush and be denigrated as English lackeys.

The second option is for the party simply to be dissolved and for unionist conservatives to join their nationalist conservative confrères in the Scottish Nationalist Party to form a united bloc of sensible people in the party. The disadvantage of this option is that the center-left leadership of the SNP will have an obvious advantage in being able to shut out any former Tories from party positions. The anti-Tory cultural bias is so strong that expulsion may even be considered.

Still, if the SNP wants to be both the party of the Scottish people and the party of Scottish government it would be wise to fulfill two tasks: wooing Scottish Conservatives and reacting to the electorate’s reticence towards full independence. Despite the SNP having 47 seats in Holyrood to the Conservatives’ 17, the Scottish Conservatives are believed to have a larger membership than the Nationalists. Feet on the ground are one of the more important factors in winning elections, and the end of the Scottish Conservative Party could shift a great number of party activists into the SNP camp. On the second point, polls show the Scots voting down independence but being nonetheless dissatisfied with the state of the Union. Rather than the current process of revisiting which powers are “reserved” (kept in London) and which are “devolved” (decided at Holyrood) every few years, it might be better to seek a new concept of union altogether, with the preponderance of governmental power shifted from Whitehall to Belfast, Edinburgh, Cardiff, and English MPs voting on English affairs at Westminster (though some have suggested creating a new English parliament).

The danger here is that any significant reappraisal of the constitutional framework of the Union at this moment might result in any or all of the following: 1) even more power for the government; 2) a step towards the total dissolution of the Union; 3) republican moves towards the abolition of the monarchy. Unionist conservatives ought to oppose all three and nationalist conservatives should at least join in opposing further centralization and the abolition of the Crown, both of which would result in removing any checks on the power of Britain’s political class.

Indeed, perhaps that is the cause around which conservatives of all stripes should unite: opposition to the political class which has seized control of almost all the major institutions of public life in Great Britain and which guards its power jealously. The current political class, which replaced a more multifaceted Establishment (consisting of the commercial class, aristocrats, bishops, do-gooding campaigners, skillful parliamentarians, trade unionists, and the British officer corps) consists almost wholly of boring people who are carbon copies of one another. The fact that no political party currently opposes this political class and its consensus is likely the reason why Britons are so apathetic and unlikely to vote in elections. Peter Hitchens has suggested the first thing that must happen for this situation to change is for the Conservative Party to self-destruct and cease to exist. There are still in Britain today many deeply-conservative people who nonetheless vote Labour (or Lib Dem or SNP) because they feel culturally obliged to, or because they have inherited the bias against the Conservatives. Hitchens posits that the existence of the Conservative Party and the cultural hatred of it are the only factors which keep Labour going as a single party. If the Conservatives collapse, then Labour is soon to follow it (in this hypothesis) and once these two deep-seated “brands” are destroyed, there is finally the possibility of a truly conservative political force emerging; union-wide, not just in Scotland.

[First published in Taki’s Magazine]

Norn Iron Unites

What issue could be so important that it unites Northern Ireland’s four main political parties? The leaders of the Democratic Unionist Party, Sinn Féin, the Social Democratic & Labour Party, and the Ulster Unionist Party (to name the parties, from largest to smallest in number of votes) have written to Westminster MPs urging them to oppose the extension of the 1967 Abortion Act to Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland was exempt from the Act legalizing abortion in Great Britain because at the time it had its own parliament handling regional issues. The six Irish counties that have remained in the Union are the most strongly anti-abortion part of the United Kingdom.

“Brideshead” Regurgitated

Well, the trailer for the film adaptation of Evelyn Waugh’s classic novel “Brideshead Revisited” is out, and the film is slated for a summer release here in the States. (Trailer | Official Site). Waugh fans can but lament that, whereas Waugh said the book was essentially about “the operation of divine grace”, the screenwriter of this adaptation openly admitted that the script “turns God into a villain”.

Rather than being bold and creating a genuine work of cinematic art to match the novel, they’ve decided to take the easy and conformist route and do a God-hating rompy flick. (Because we can’t have too many of those!). A shame, of course, but entirely predictable. Shall we at least have a look at the cast?

Cry God for Britain, Harry, and St. Aidan?

“St Aidan unites three of the countries by having lived there,” Dr. Bradley says, “and is, I believe, a better symbol for Britishness” [than the George, Andrew, and Patrick, the patrons of England, Scotland, and Ireland respectively].

“It’s like Billy Bragg says in his song ‘Take Down the Union Jack’ about Britain; ‘It’s not a proper country, it doesn’t have a patron saint’. Aidan was the sort of hybrid Briton that sums up the overlapping spiritual identities of Britain.

“He also makes a good patron saint of Britain because of his character. He was particularly humble and believed in talking directly to people. When he was given a horse by King Oswald of Northumbria, he immediately gave it away because he was worried that he would not be able to communicate properly.

“He was also not shy of reprimanding the mighty and powerful about their failings. He saw it as part of his job to remind secular rulers not to get above themselves. At a time when we are thinking about what makes Britishness, he had a sense of openness and diversity for his time that I think makes him a good candidate as the patron saint of Britain.”

Find out more in this article:

“Home-grown holy man” (The Independent, 23 April 2008)

On a somewhat similar note, here’s Aelianus (one of our favourite bloggers) writing on British Identity last September.

The Sad State of the Modern Newspaper

…and the heroism of an Anglo-Hungarian countess.

IT IS ONE OF THE more saddening facts of life that British newspapers have suffered an inexorable decline in the past few years. The great Times of London – once the most respected newspaper in the world – has been reduced to a boring mid-brow tabloid, the once-solid Scotsman idiotified and, again, tabloided, and of course the Daily Telegraph, which has gone from staunchly conservative (as in worldview) to merely Conservative (as in the tribe of Britons who prefer blue to red).

The Telegraph, like the Conservative party itself, doesn’t seem to know what it’s there for. It has at least remained a broadsheet; going tabloid would be a disaster and would probably be considered the last straw for all the die-hards for whom loyalty to one’s newspaper is a point of pride. And, to its credit, it finally seems to have realised the damage done by constant front-page photos of “Posh” and “Becks” and other “celebrity” partisans of the Anti-Culture, for they seem fewer and far between these days (as compared to a year or two ago, when they were frequent). The Telegraph‘s base are old folk who want a quality newspaper. They are loyal to the Tele and, despite its decline, would be too embarrassed to jump ship to the Guardian, which is written better but which nonetheless expones a nefarious ideology.

As for myself, the last straw came one morning in the Common Room of St. Salvator’s Hall when, flipping through the Telegraph, I reached the page which normally displays the Court Circular but found it missing, replaced by a curt statement advising that should I desire information about the activities of the Royal Family I should direct myself to http://www.royal.gov.uk. Outrageous! As it happens, this is not a permanent loss but rather an occasional one, as the editors at the Telegraph seem to decide whether or not to print the Court Circular each day on a whim. Fair enough, but I came to the realisation that the producers of the Telegraph are not aiming at me – the reasonably educated young man who seeks in his daily read a newspaper that is well-written, right-thinking, and properly presented – and so I have ceased to be a Telegraph regular.

What to read then? We have already dismissed the Times, the Scotsman, and the Guardian. The Daily Mail is always readable but arguably aimed at a different demographic; the Daily Mirror, bonkers; the Sun, no thank you!; the Financial Times is too boring, though the Weekend edition is actually worth buying most of the time; the Independent has a good layout for a tabloid, but is rather of a Lib-Dem persuasion; the Glasgow Herald is just rather dull and has only recently repented of its long-held anti-Catholicism. Not wanting to support the nefarious New York Times, enemy of Western civilization and the last word in liberal elitism, its wholly-owned subsidiary the International Herald-Tribune is ruled out. Which pretty much rules out every English language daily newspaper available in St Andrews.

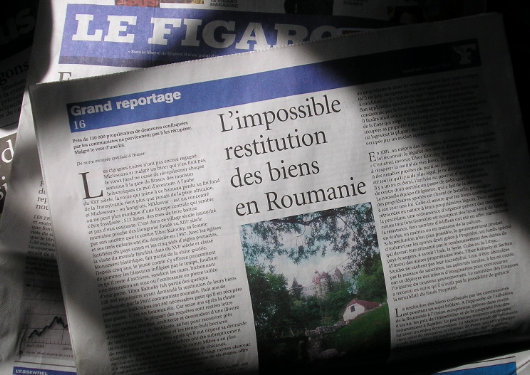

So, abandonné par ma langue, I have outsourced my daily read to the Continent (of all places!) and am now a partisan of Le Figaro. While by no means fluent in the language, I can comprehend written French with greater ability than I speak it. And while I still prefer the feel of a broadsheet, the Berliner size of Le Figaro has its advantages, being very easy to read in the confined space of my regular chair in the corner of the little coffee shop down the street. More importantly, I find it much more engaging mentally, which I put down to the fact that (not being a native or fluent French speaker) I am forced to read every word. Reading the Telegraph one unthinkingly only actually reads every third or so word; articles of particular interest excepted, naturally. The day’s Figaro usually arrives in the middle of the day or the afternoon, but I buy my paper in the morning so actually I’m usually reading the previous day’s Figaro. I don’t mind, it suits my current routine. (Mornings are for reading the newspaper in a coffee shop, afternoons are for reading books with a slow pint in the pub.)

So, abandonné par ma langue, I have outsourced my daily read to the Continent (of all places!) and am now a partisan of Le Figaro. While by no means fluent in the language, I can comprehend written French with greater ability than I speak it. And while I still prefer the feel of a broadsheet, the Berliner size of Le Figaro has its advantages, being very easy to read in the confined space of my regular chair in the corner of the little coffee shop down the street. More importantly, I find it much more engaging mentally, which I put down to the fact that (not being a native or fluent French speaker) I am forced to read every word. Reading the Telegraph one unthinkingly only actually reads every third or so word; articles of particular interest excepted, naturally. The day’s Figaro usually arrives in the middle of the day or the afternoon, but I buy my paper in the morning so actually I’m usually reading the previous day’s Figaro. I don’t mind, it suits my current routine. (Mornings are for reading the newspaper in a coffee shop, afternoons are for reading books with a slow pint in the pub.)

The chief deficit of reading a French newspaper is that naturally the news is oriented towards France, and thus I don’t get the usual transatlantic focus of the British papers (which can be an advantage as well as a deficit, I’ll concede). Nonetheless, it does happen to have articles of interest to any trad.

A few weeks ago, Le Figaro reported on the restitution of Romanian castles to their original, pre-Communist owners (‘L’impossible restitution des biens en Roumanie’, Le Figaro, 21 April 2006). The New York Sun rather amusingly and provincially headlined the story “Westchester Man To Take Possesion of Dracula’s Castle” — the New York Post characteristically used the headline “VLAD TIDINGS“. (FTD also reported on the restitution of Bran). When I wrote my previous post on the subject I was under the impression that Bran was one of the castles which would be restituted and then purchased back by the Romanian government, but most sources imply that this is not the case and Dominic von Habsburg (of North Salem, New York) will actually take possesion of the castle, I’m glad to hear.

This morning, then, I read in Le Figaro of the controversy surrounding a red star which remains on a Soviet war memorial in a small town in Hungary, a country which has banned all Communist and Nazi emblems (‘Hongrie: Le pasteur, la comtesse et l’étoile rouge’, Le Figaro, 6 May 2006). The local Protestant minister has been fighting to replace the red star, and has found an ally in Countess Jeanne-Marie Wenckheim-Dickens. The Countess, aged 70 and a descendant of Charles Dickens, returned to Hungary a few years ago after her husband died. The family had fled the country in 1944 just escaping the conquering Red Army. “I return home,” the Countess says (‘with a delicious British accent’, Le Figaro reports), “and what do I find? My castle transformed into an elementary school with, right in front of the gate, a red star! To me, this star is the Antichrist.”

The Countess funded the restoration of her former castle, now a school, and obtained permission from the town to live in the old presbytery, an ancillary building of the old castle. But when, in 2004, she proposed to mark the accession of Hungary to the European Union by replacing the red star on the monument with a European flag, the ex-Communists in the town hall told her she “should not be afraid of the red star, but of the Cross!” With fighting spirit, “I placed a large cross on my entryway,” the Countess says, “then I painted it gold so that the Mayor, whose window is opposite, can see it all the better.”

“Crosses? She can build a hundred of them!” the Mayor said. “It doesn’t disturb me!” But in return the Mayor had a house on what was the domain of the Wenckheim family renovated for the use of unemployed local gypsies. “It was clearly to annoy me,” the Countess said. “They thought the gypsies were going to make the area around the nearby church, built by my grandfather, filthy. But not at all! They respect the place, and I, I love their music very much.” The Countess also gives weekly catechism lessons to the local gypsies. In her window, she displays a letter to the people of the town inviting them to vote for the conservative Fidesz party. “In December,” the Countess continues, “before Christmas, I add little angels and holy pictures; they don’t like that much across the way, since they’re aimed at the town hall. Because I, too, have a star: but is the star of the Shepherd”.

The English Tower and Kavanagh Building

THE SAYING GOES that Argentines are all Italians who speak Spanish and want to be English, which is only just short of the truth. Whatever the quip’s verity, Argentina is a nation of the expatriated and for the centennial year of the 1810 May Revolution, the communities from each of the major mother countries — Spain, Italy, Germany, et cetera — built monuments in dedicated places both to commemorate the contributions their kinsman made to their adopted country as well as to celebrate peace and friendship between Argentina and the given motherland. The Plaza Italia, for example, lamentably bears a monument to the scoundrel Garibaldi, donated by the Italian community.

THE SAYING GOES that Argentines are all Italians who speak Spanish and want to be English, which is only just short of the truth. Whatever the quip’s verity, Argentina is a nation of the expatriated and for the centennial year of the 1810 May Revolution, the communities from each of the major mother countries — Spain, Italy, Germany, et cetera — built monuments in dedicated places both to commemorate the contributions their kinsman made to their adopted country as well as to celebrate peace and friendship between Argentina and the given motherland. The Plaza Italia, for example, lamentably bears a monument to the scoundrel Garibaldi, donated by the Italian community.

For their monumental contribution to the city of Buenos Aires, the English built a tower in the Edwardian style, rather cleverly as it was still the Edwardian period, and the depth of their cleverness was furthered by their naming it the English Tower (officially Torre de los Ingleses, or Tower of the English). Situated in the center of the Plaza Britannia (Britannia Square) at the junction of the San Martin and Libertador avenues, the Tower was designed by engineer Ambrose Poynter and built by Hopkins and Gardom completely (except for mortar) out of materials from England. Around the base are sculptural representations of the English rose, the Scottish thistle, the Welsh dragon, and the Irish shamrock. The dedication at the entrance to the Tower reads “Al Gran Pueblo Argentino. Los residentes británicos. Salud. 25 de mayo 1810-1910” or: “To the Great Argentine People, from the British residents: Salud. May 25, 1810-1910″. Towards the rear of the photo to the right you can see the Kavanagh building (Edificio Kavanagh).

The Kavanagh building is situated on the Plaza San Martin across the avenue from the Plaza Britannia. This 29-storey apartment building was designed by the firm of Sanchez, Lagos, and de la Torre, and was the tallest building in Latin America when built in 1936. The sharp art deco design on an angulated plot is said to resemble a ship at sea, and of course Buenos Aires is a port city — its residents are called porteños after all.

The Kavanagh is unquestionably my favorite ‘modern’ building in Buenos Aires, but then modern architecture has not been kind to the city, at least not in the post-war period (c.f. the National Library). The structures built in the 1950’s were only drab and dull whereas the 60’s and 70’s bore the ill fruits of the ‘lets see how many things we can do with concrete’ trend and tended towards the insidiously hideous rather than the mundane. But no matter however irritating these later obtrusions are, at least Buenos Aires still has the Kavanagh.

Despite the generations of immigration, investment, interbreeding, and cultural interchange, relations between Argentina and Great Britain were somewhat marred, shall we say, by the shameful attempt by the unhinged wing of the Argentine military to annex the Falklands and rename every geographical feature therein (seriously, I’ve seen the maps). When they were done renaming everything in the Falklands (or ‘Malvinas’ as they would have us believe) the craze apparently spread homewards to the capital. The Plaza Britannia was renamed the Plaza Fuerza Aerea Argentina (from Britannia Square to Argentine Air Force Square), while the Torre de los Ingleses was rechristneed the more ambiguous Torre Monumental. In an even more unfriendly move, the Memorial to the Fallen of the ‘Malvinas’ was built in Plaza San Martin facing the English Tower across the street. In the spirit of peace and friendship, especially regarding two countries which have such deep links as Britain and Argentina, the Memorial really ought to be removed and placed in some other suitable location in the city. Until that time, it remains the Plaza Britannia in my books, and as for the ‘Malvinas’, no such place exists.

The ‘Malvinas’ memorial viewed from the rear, with the English Tower across the Avenue.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories