Great Britain

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Sir John Soane

Sir John Soane still looms over the intervening centuries of architecture and design in Great Britain, but I’ve never actually known what he looked like. Apparently this is him, in an 1804 portrait by William Owen.

Everyone’s been to his house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, but Pitzhanger Manor, his place in the country (though Ealing hardly seems rural today) was recently reopened after serious conservation works ongoing since 2015.

Hope to pay it a visit soon.

Rosary on the Coast

By all accounts last Sunday’s Rosary on the Coast was a resounding success. The initiative started out in Poland, where last year thousands of Catholics gathered at the nation’s borders and coastline to pray for the salvation of Poland and the world. Then a month later Ireland joined in with a Rosary on the Coast for Life and Faith, encircling the country in prayer.

Last Sunday, Great Britain got in on the action, and for three countries which have suffered centuries of Protestant domination it seems we have done rather well on these shores. Thousands of people from every variety of ethnicity, class, background, and experience gathered to pray the Rosary “for the spiritual wellbeing of our nations” (as the organisers put it).

The Rosary on the Coast was organised by lay people but supported by the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster as well as many other bishops and of course priests, many of whom accompanied and led in prayer the lay-organised groups around Britain. The rectors of the three national Marian shrines at Walsingham in England, Carfin in Scotland, and Cardigan in Wales all gave their backing and encouragement to the initiative.

Experience has taught me not to be surprised by the success of such ventures. I remember when the Cardinal renewed the consecration of England & Wales to the Immaculate Heart of Mary (with the visit of the Fatima visionaries’ relics). I didn’t have plans to go but friends were driving in from the West Country for it so I thought I’d meet up with them beforehand and go along.

We tried to get in but the doors of the cathedral were shut and a crowd waiting outside – it turned out the church was packed to the gills with the faithful. A pint later we tried again and they had just reopened the doors and let us in. Every bit of the mother church of the diocese was crammed with people, from Filipino maids to peers of the realm. Pews, aisles, side chapels – there was barely room to move. Priests were hearing confessions and the service was ongoing. We’re so used to being an embattled minority that sometimes we forget that we’re still the biggest show in town.

The good people at the Catholic Herald have collected a variety of photos from around the country, of which just a small sample are presented here. (more…)

Earls, Shires, Hides, and Hundreds

What the Practice of ‘Pricking the Lites’ Tells Us About Territorial Division in Anglo-Saxon England

As cheekily noted by Ned Donovan on his Twitter feed, HM the Q has recently engaged in the old practice of ‘pricking the lites’ to appoint High Sheriffs for the three ceremonial counties of Lancashire, Greater Manchester, and Merseyside. But in order to know what ‘pricking the lites’ is it’s worth looking at the territorial division of Anglo-Saxon England and the old offices that emerged therefrom.

In those days, the land was divided into hides, a hide being the amount of land on which a family lived and supported itself. Ten hides together were known as a tithing, and ten tithings were collectively a hundred.

As hundreds go, the best-known today are the Chiltern Hundreds because of the parliamentary role they play. Members of Parliament are not allowed to resign, but nor are they allowed to hold an office of profit under the Crown.

So whenever an MP wants to resign, he or she is appointed Crown Steward and Bailiff of the three Chiltern Hundreds of Stoke, Desborough, and Burnham and, having accepted such office, is deemed to have disqualified themselves from continuing to sit in the House of Commons. (The Manor of Northstead is also used alternately with the Chiltern Hundreds.)

Anyhow, each hundred was supervised by a constable, and groups of hundreds were collected into shires. Each shire was overseen by an earl, of whom the French equivalent is a count, so after the Normans turned up shires became more often known as counties. These now divvy up territory across the English-speaking world, from Kenya to California.

Each level of these Anglo-Saxon divisions had a relevant court for decision-making, and the officer who administered or enforced these decisions was known as the reeve. Amongst these titles – town-reeve and reeve of the manor, etc. – there was the shire-reeve, or sheriff as it was contracted.

In the 1970s, for reasons unknown to me, all the sheriffs in England & Wales were elevated to high shrievalties.

Every February or March, a parchment is prepared for the Queen in her capacity as Duke of Lancaster with three names of candidates for high sheriff in the three current ceremonial counties covered by the old duchy. This parchment is known as the lites (a cognate of ‘list’, I believe).

At a meeting of the Privy Council, the Queen takes a silver bodkin and pricks the parchment next to the name of the candidate she chooses to be high sheriff. In practice, this is always the first name on the list, and customarily the following names move up a notch and serve in later years.

A similar process takes place for the Duke of Cornwall to appoint their high sherriff but without the aid of the Privy Council.

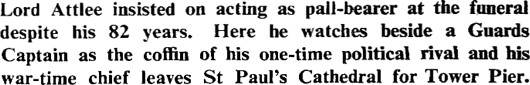

Supermac and the Sarduana

Macmillan’s Attitude to Class and Race in the Late Empire

Left: Harold Macmillan touring Africa in 1960; Right: Sir Ahmadu Bello, the Sarduana of Sokoto.

Staying over with some Kenyan friends in Wiltshire the other day, the old observation came up that, after the war, the officers settled in Kenya while the sergeants went to Rhodesia. While some of the leading lights of UDI had, in fact, been officers — Ian Smith an obvious case — it’s interesting to note that most of them came from humble backgrounds.

“Smithie” was born well-off in Rhodesia but his father had been a butcher’s son who went out to Africa and made good. Clifford Dupont, the first president of the Rhodesian republic, was born in London of poor East End Huguenot stock. His father had done well in the rag trade and got his son to Cambridge; Clifford became an artillery officer before emigrating to Africa.

Rhodesian Prime Minister Roy Welensky’s father was a Russian Jewish horse smuggler who married a ninth-generation Afrikaner. Roy was the couple’s thirteenth son, and left school at 14 to work on the railways and found success through the trade union movement.

Harold Macmillan, meanwhile, was a Guards officer and Old Etonian who had studied at Oxford. His famous ‘Wind of Change’ speech was just part of the British prime minister’s grand tour of Africa. “Supermac” started in Nigeria, where — unlike in some other parts of the continent — much of the native aristocracy had been preserved and coopted throughout colonial rule.

Proving Orwell’s observation that the English are the most class-ridden nation on earth, the PM felt comfortable amongst black African patricians in a way he couldn’t amongst members of the ruling white African elite from humble backgrounds.

In one of the ICBH’s oral history group discussions, Perry Worsthorne relates:

Somebody at some point has to mention, in any discussion of British politics, snobbery and class. I remember travelling and reporting on the ‘Wind of Change’ speech. We went to stay on the last bit, just before going on to Salisbury, was it the Sardauna of Sokoto who was he the premier of the Northern Nigerian region. Macmillan talked to us after he had seen him, he was flying on to Welensky the next day.

Macmillan used to have a sundowner with the correspondents covering his trip, and over whisky and sodas he told us how much more at home he felt with the Sardauna, who reminded him of the Duke of Argyll – ‘a kind of black highland chieftain’ – than he would feel in Salisbury as the guest of a former railwayman, Sir Roy Welensky. Snobbery, pure snobbery.

The British metropole was always ready to make racial distinctions and discriminate accordingly, yet it still tended to look upon outright racism with an air of disdain, as something slightly unsporting (or worse: foreign).

In the imperial periphery, racial attitudes amongst whites often differed greatly from Britain. This was most obviously so in South Africa, which for all intents and purposes embarked upon a radical revolutionary rejection of the British model of governance from 1948 with the implementation of apartheid. Rhodesia, needless to say, was another exception, if arguably more mild. “How different it would all have been,” Worsthorne somewhat patronisingly wondered, “if Ian Smith had been a gentleman.”

Meanwhile Nigeria’s Sir Ahmadu Bello — the Sarduana of Sokoto — was a statesman of cautious action, and his refusal to become Nigerian prime minister upon independence (he preferred sticking to his existing role as the powerful premier of the northern province) sadly deprived the federal state of the wisdom and experience which may have prevented its later descent into disarray. He was murdered by Major Nzeogwu during the 1966 coup d’état.

Differences of race or class aside, it’s telling that both the white low-born railwayman Welensky and the black patrician Bello ended up as knights of the realm.

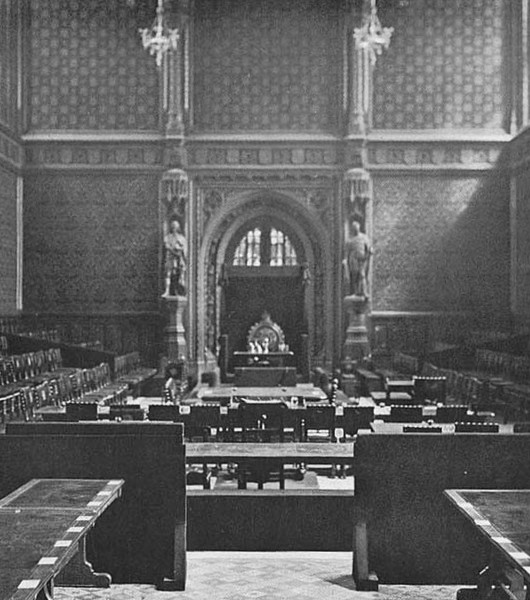

Justice in the Royal Gallery

One of the great triumphs of Magna Carta was the assertion of the right of those accused of crimes to trial by one’s peers, or per legale judicium parium suorum if you insist on the Latin. For commoners this meant trial by other commoners, but for peers it meant just that: trial by other peers of the realm. It was a bit murkier for peeresses, though after the conviction for witchcraft of Eleanor, Duchess of Gloucester, (sentence: banishment to the Isle of Man) statute was passed including them in the judicial privilege of peerage.

Thanks to the ’15 and the ’45, there were a number of trials in the House of Lords in the eighteenth century, including that of the Catholic martyr Earl of Derwentwater. The whole of the nineteenth century, however, witnessed but one: the 7th Earl of Cardigan was acquitted of duelling by a jury of 120 peers. In 1901 the 2nd Earl Russell was found guilty of bigamy, and the last ever trial came in 1935 when the 26th Baron de Clifford was found not guilty of manslaughter.

Cardigan’s trial was in the temporary Lords chamber while the last two trials took place in the Royal Gallery of the Palace of Westminster (central to current debates over renovation plans). For Cardigan’s trial the Lord Chief Justice of the Queen’s Bench was appointed Lord High Steward for the occasion, while for the final two the Lord Chancellor was likewise appointed to the role in order to be presiding judge with the Attorney General prosecuting the case.

The Royal Gallery is primarily used for the State Opening of Parliament (as above) and for the occasional address to both Houses of Parliament when important figures are invited to do so. De Gaulle was famously invited to speak here to both houses rather than in the larger Westminster Hall. It is thought that this is because the walls of the Royal Gallery feature two large murals, one of the Battle of Trafalgar, the other of the Battle of Waterloo – both British victories over the French.

The most famous trial in the Royal Gallery was fictional. In the 1949 Ealing comedy “Kind Hearts and Coronets”, the 10th Duke of Chalfont is tried for the one murder in the film’s plotline he didn’t actually commit. Ealing Studios did a mock-up of the chamber for the occasion (above), which compares reasonably accurately with the Royal Gallery as set up for the Baron de Clifford’s trial in 1936 (below).

The Lords, however, were uncomfortable with exercising this judicial function and passed a bill to abolish the privilege in 1937. The Commons, facing more serious tasks, declined to give it any attention. In 1948, the Criminal Justice Act abolished trials of peers in the House of Lords, along with penal servitude, hard labour, and whipping.

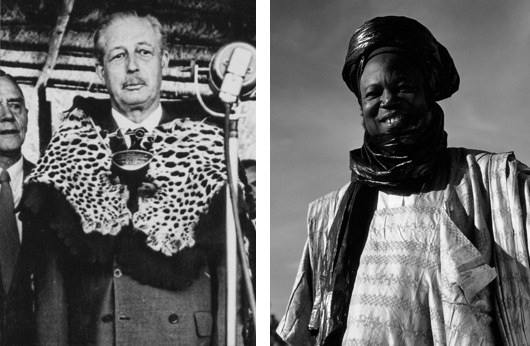

The Earl Attlee

At Chartwell one weekend in Churchill’s presence, Sir John Rodgers made the mistake of referring to Clement Attlee, wartime deputy prime minister and postwar prime minister, as “silly old Attlee”. Churchill was having none of it.

“Mr Attlee is a great patriot,” he said. “Don’t you dare call him ‘silly old Attlee’ at Chartwell or you won’t be invited again.”

The leader of the Conservative party and the leader of the Labour party were obvious political rivals but developed a great bond by their shared experience in the cross-party War Cabinet.

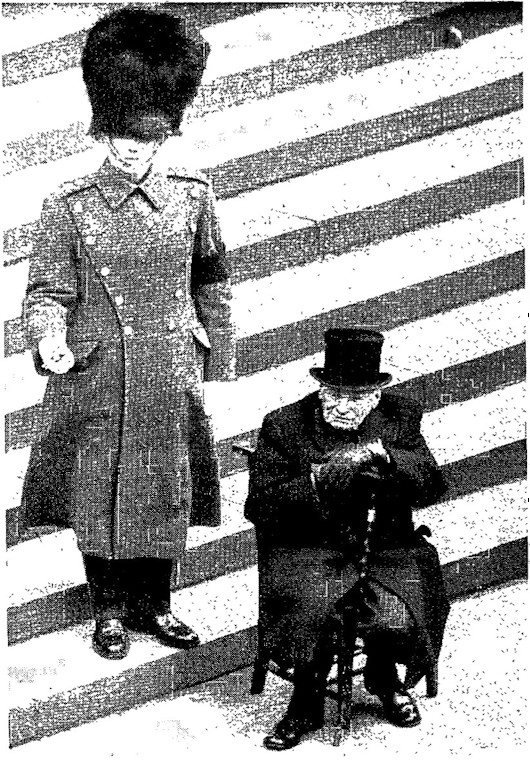

En route to a dinner party the other night I happened to run into Attlee’s greatgrandson (an old friend) on the upper deck of the 414 bus. It reminded me of this photo (above) printed in the Observer. When the great bulldog went on to his eternal reward in 1965, the incredibly frail Earl Attlee insisted on attending the state funeral in St Paul’s Cathedral. Though younger, he only managed to outlive him by two years.

Attlee had been raised to the House of Lords (where he spoke against Britain joining the EEC) in 1956 and, rather appropriately, he chose as the motto for his coat of arms Labor vincit omnia — Labour conquers all.

Challoner’s House

Challoner’s House — Rather humble for an episcopal palace, but such was the function of No. 44, Old Gloucester Street in Holborn during the time of Bishop Richard Challoner.

If it seems an odd spot for London’s Catholic bishop, it can be explained by its close proximity to the chapel of the Sardinian Embassy off Lincoln’s Inn Fields. At this time, of course, the Mass was still illegal and the only places Catholics in London could worship were the embassies of the Catholic nations. To protect the underground bishop, the house in Old Gloucester Street was actually rented in the name of his housekeeper, Mrs Mary Hanne.

After a perfect breakfast on Saturday morning the sun was shining so I decided the three-and-a-half miles home from St Pancras were best managed on foot. If architectural or historical curiosities are your fancy then foot is the way to travel, and so it was by pure chance that I stumbled upon No. 44. It seemed particularly appropriate that the night before a whole gang of us — Brits, Swedes, Italians, etc. — had been drinking in the Ship Tavern in Holborn where Bishop Challoner was known to offer the occasional clandestine Mass. (more…)

The Delarue Proposal for Parliament

Peers & MPs could still convene in the Palace during renovations

The Royal Gallery set up for temporary use as the House of Lords chamber

Credit: Anthony Delarue Associates

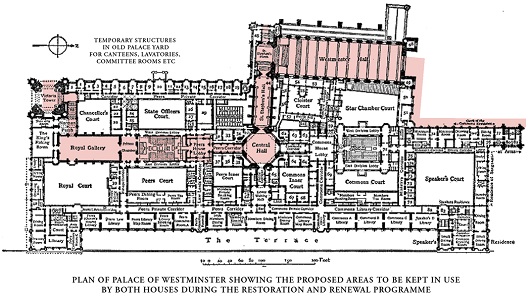

MPs are kicking up a fuss about the controversial proposals to shut down the entire Palace of Westminster for perhaps as long as eight or nine years. (Previously mentioned here.) The building is completely structurally sound, and on solid foundations, but the accumulation of mechanical, electrical, and technological systems over the course of the past 150 years has created a confused mess within the walls of the palace. Electrical lines compete with fibre-optic cables, telephone wires, not to mention various heating and cooling pipes, and even some lingering telegraph wires. No one’s quite sure what is what and all of it is getting older. Even just accessing it to figure out what to do requires taking the building apart — removing wood panelling, drilling through walls, etc.

Parliamentary authorities commissioned management consultants from Deloitte to come up with a number of options on how to tackle this problem, but in their Independent Options Appraisal they treated this merely as an ordinary engineering job, rather than recognising the Palace as one of the most important places in British history both medieval and modern and, importantly, one still in constant daily use.

The Joint Committee formed of members of both the Lords and Commons perhaps unsurprisingly endorsed the option Deloitte claimed was the quickest and cheapest: that the Lords, Commons, and everyone else be chucked out of the Palace entirely and that temporary accommodation be found nearby.

Further investigation by respected former minister Shailesh Vara MP suggested that Deloitte had failed to take into account that any VAT costs on this major project go back into the Treasury anyhow, and that there was a failure to account for the loss of revenue if the Lords are moved into the government-owned Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre nearby. The QE2 is a profit-making venue popular with private clients, after all, and deploying it towards full-time legislative use will mean another significant loss for the Treasury. Meanwhile, in the courtyard of Richmond House on Whitehall, £59 million would be spent on building a new chamber for the House of Commons. This would be a permanent ‘legacy’ structure even though once the renovations to the Palace are complete there would be no use for it whatsoever.

The architect Anthony Delarue, having been taken on a tour of the Palace’s working underbelly by the engineers from the Restoration and Renewal programme, came up with an alternative proposal. Looking at the structure of the House of Lords chamber and the adjacent Royal Gallery, he realised that these two rooms could be maintained and occupied, with temporary services (electricity, heating, etc.) run from external sources. This would allow the renovation team to shut down the Palace’s systems entirely and re-do them completely, while the spaces in mind would still be able to be put to use. The Commons could then meet in the Lords chamber (as the wartime precedent suggested) and the Lords could meet in the Royal Gallery. Or indeed vice versa depending on the wishes of both Houses.

The advantages of this are no need for taking up the QE2 conference centre (with consequent loss of revenue for the Treasury) and no need to waste tens of millions on a temporary-but-permanent Commons chamber in the courtyard of Richmond House. In addition, both houses would be allowed to maintain their presence in the Palace of Westminster, in accommodation suitable to the traditions of the “Mother of Parliaments”.

Of course, the Restoration and Renewal programme ran a “high level review” of Delarue’s proposals and pooh-poohed the whole idea, amazingly claiming that it would probably cost £900 million more than the Deloitte option the Joint Committee preferred. Anthony Delarue has now written some comments responding to this review, pointing out that it relies on outrageously pessimistic estimates of timing, assumptions that are beyond the worst-case scenarios of project management.

MPs were expected to debate the matter last month, but the campaign organised by Sir Edward Leigh MP and Shailesh Vara MP has found considerable support among other Members of Parliament and it is believed the powers that be are looking for a delay. The Government have promised a free vote on the issue when it comes up for debate, which may very well be before the end of February.

● Anthony Delarue Proposal

● Deloitte Independent Options Appraisal

● Joint Committee Report

● High Level Review of Delarue Proposal

● Anthony Delarue Response to High Level Review

Credit: Anthony Delarue Associates

The Queen

1992; Oil on canvas, 96 in. x 60 in.

Mendicant Architecture in Mediaeval Oxford

An interesting video from two American academics on the subject of Mendicant architecture in mediaeval Oxford, with some three-dimensional theoretical reconstructions of the Dominican and Franciscan houses in the city.

Both orders returned to Oxford in the twentieth century. The Capuchins refounded Greyfriars in 1910 and it was recognised as a permanent private hall (PPH) of the University in 1957. Its end as an academic institution was announced sadly on its fiftieth anniversary in 2007, but Greyfriars continues as a Capuchin friary.

Blackfriars under the Dominicans is still going strong, exercising a triple function as a priory of the Order of Preachers, a house of studies for the English province of the Order, and a PPH of the University of Oxford.

Judging Dress

After some absence, The Sybarite has returned and, in A Love Supreme, he weighs in on the very important matter of judicial dress.

I am, it will surprise no-one to know, deeply traditionalist in such matters. I can see the argument for discarding formal court attire in cases involving children, who might be intimidated by wigs and gowns (as a child, I myself would have been as happy as a pig in the proverbial). But I feel strongly that “work clothes”, whether worn by judges, barristers, politicians or clerks in Parliament, are important. They are part of the persona. You are not Alf Bloggs, you are Mr Justice Bloggs and you are performing an important public role. When you put on the clothes, you put on the role. Of course, I am fighting a rearguard action here – I know that the tide of public opinion is against me. If the clerks at the Table in the House of Commons still wear wigs in ten years’ time, I will be (pleasantly) surprised.

As the Supreme Court was set up in the modish New Labour years, it was inevitable they would dispense with much of the ceremonial. The Justices wear lounge suits to hear cases, though I think in some cases the barristers still wear wigs and gowns. The one concession has been the black-and-gold gowns which the Justices don for special occasions. These are fine so far as they go – and, as observed above, Lady Hale of Richmond likes to accessorise hers with a Tudor bonnet – though they bear on the back the badge of the Supreme Court, which I think looks a bit tacky and smacks of footballers’ names and numbers on the back of their shirts. But they also look a bit odd worn over lounge suits or equivalent. At least successive Lord Chancellors since the role was recast by Blair have retained formal court dress for high and holy days. Mind you, the current occupant, Miss Truss, does look a bit like the principal boy in a pantomime when she wears knee breeches. But fair play to her for continuing to wear the traditional robes, even if the full-bottomed wig seems now to have gone the way of the dodo.

It could be worse. The Supreme Court Justices could wear ghastly zip-up gowns like their American counterparts – you just know they’re made of nylon – over their suits, though I have some time for Justice Ginsberg for adding a lace jabot to tidy up her garb a little. But ceremonial is something that Britain does so well. The Supreme Court could have looked so much better with Justices in gowns and traditional judicial clothing. A wig here and there wouldn’t go amiss.

I couldn’t agree more. Especially on the matter of the badge of the Supreme Court on the back on the gowns, which is simply naff. (See image below.)

But why do the justices of the Supreme Court have (what I think of as) chancellorial gowns anyhow? What is the origin of this style of black-and-gold gown? Did it start with the Lord Chancellor and spread to the Speaker or vice versa? Or have some species of judge always worn chancellorial gowns? The chancellors of universities have likewise adopted it, though its precise form varies from institution to institution, as one might expect in matters of academic dress.

Incidentally, I was speaking with Bob Geldof the other day about Senator W. B. Yeats, about whom Mr Geldof has done a documentary. As we were discussing Yeats’ contribution to the Irish Senate, Mr Geldof mentioned that Yeats had been in discussions with Hugh Kennedy, the Chief Justice of the Irish Free State, about introducing new designs for Irish judicial dress. The results, according to just about everyone, left much to be desired and so the British tradition carried on for the most part. As is so often the case, doing nothing is the least bad option.

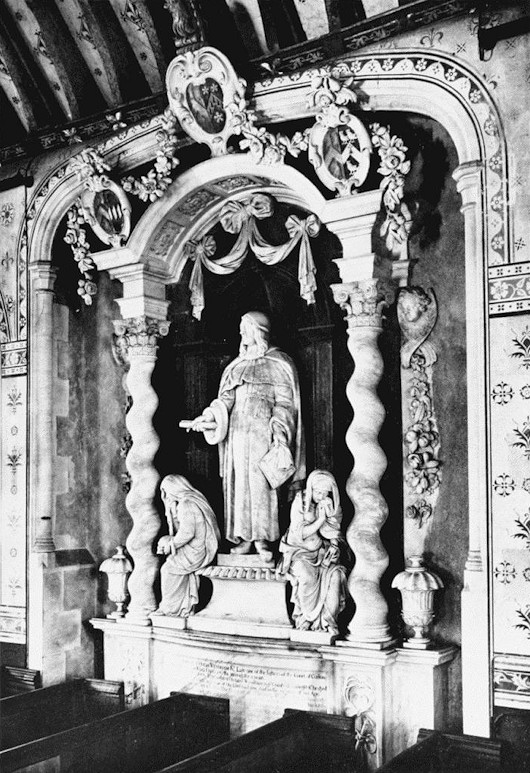

The Wyndham Monument, Silton

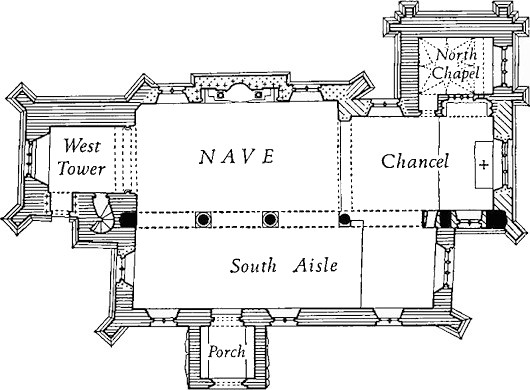

The charmingly haphazard Church of St Nicholas in Silton is home to what is arguably the finest funerary monument in Dorset not in a major church.

Sir Hugh Wyndham (1602–1684) lived through the difficult time of the Civil War and was first advanced in the law under Cromwell’s military dictatorship. It was the worst of both worlds for Wyndham, as the republican authorities never trusted him while after the Restoration his comfort with Cromwell meant he was deprived of office. Still, Charles II was no small-minded man, and after a royal pardon was granted Wyndham was appointed a Baron of the Exchequer and knighted.

The monument he left behind at Silton is is believed to be the earliest work of the Flemish sculptor Jan van Nost (also known as John Nost the elder). Sir Hugh is depicted in his judge’s robes, flanked by two mourning figures believed to represent his first and second wives. (The third wife is at least represented by having her arms impaled with Wyndham’s in one of the three heraldic sheilds gracing the monument’s surrounds.)

Nost’s sculpture was unveiled in the chancel of the parish church in 1692 but the Victorians thought it rather dominated the small sancutary. In 1869 a small recess was constructed in the north wall of the nave and the Wyndham monument was carefully moved there. The sculptor was also responsible for the monument to John Digby, 3rd Earl of Bristol, in Sherborne Abbey not far away, and one can see the parallels. The Earl, as it happened, married Rachel Wyndham, the younger daughter of Sir Hugh Wyndham.

Letter to the Editor

A letter to the editor printed in this week’s edition of The Tablet:

Brendan Walsh’s report (“Heythrop’s fate”, 17 September) of a senior academic suggesting that the demise of Heythrop was an episode in a long struggle between “outward-facing, inquisitive, challenging” theology on one side and “inward-looking, submissive, unquestioning” theology on the other is telling.

Positing such a simplistic binary split between Enlightened Me and Poor Ignorant You is patronising to those attempting to live out the radical beauty of the Christian life in tune with Catholic teaching. It’s not surprising that an institution with academics holding this view is entering its death spiral, while religious communities that don’t consider basic orthodox belief as optional are bursting at the seams.

Few things are more challenging – and more rewarding – than faithfulness; while some cling to clapped-out heterodoxies and managed decline, the rest of the Catholic world has moved on.

ANDREW CUSACK

London SW1

A Fifty Pound Note

The recent arrival of the new fiver has caused some flurry of excitement and one of the notes finally reached the Cusackian exchequer via the barmaid at the Ox Row Inn in Salisbury on Friday night. I’m indifferent to the design; it’s inoffensive but I’d prefer to see Churchill depicted in his coronation robes rather than Yousuf Karsh’s iconic photograph.

My favourite Bank of England note, however, remains the Series D £50 first issued in 1981 designed by the Black Country artist Harry Eccleston. Sir Christopher Wren lookings crackingly baroque, and St Paul’s Cathedral looms like a great ship over the City of London he helped to rebuild after the Great Fire 350 years ago.

Eccleston was the first banknote designer to work fulltime for the Bank of England which he joined in 1958, retiring in 1983, and introduced the concept of historical figures from British history gracing the back of the notes (which are of course fronted with an image of the Sovereign). This particular note was the first fifty-pound note to be issued since 1943. It was replaced in 1994 and withdrawn from circulation two years later.

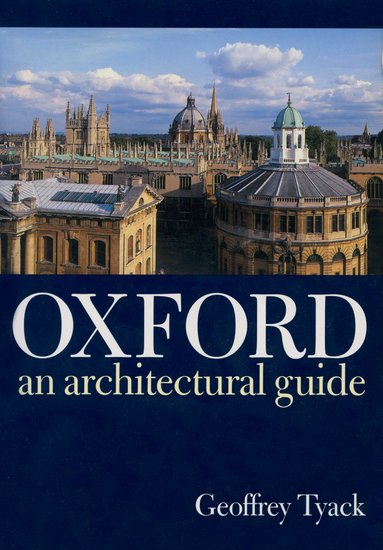

Oxford: An Architectural Guide

Oxford: An Architectural Guide

Oxford: An Architectural Guideby Geoffrey Tyack

OUP (1998), £16.99, 384 pages

Geoffrey Tyack writes with a fluid style that accesibly conveys a great amount of specific detail of people, places, materials, and more without the reader feeling the least bit overwhelmed. Even the most veteran Oxonophile will gain deeper insight into what buildings were built by (and for) whom, with what money, and how they’ve been adapted over the centuries. A model guide to the architecture of the finest university town in the world.

Flags, Northern Ireland, and the Union

Flags have been in the news of late, perhaps as a late hangover of the disruptive protests over Belfast City Council’s decision to fly the Union Jack from Belfast City Hall only on the United Kingdom’s designated flag-flying days. Ironically, this would have brought the Six Counties further in line with normal British practice, but disgruntled unionists viewed it as a diminution of “their” flag and a bit of a fracas ensued with the once-traditional death threats and intimidation returning.

The BBC raised the issue of how Scottish independence might affect the Union Jack. (Pedants only refer to the British flag as the “Union flag”, but the Flag Institute points out both terms are perfectly acceptable). Scottish independence would have no automatic effect on the flag whatsoever, but it has provoked a round of speculation over what changes, if any, should be made to the Union flag.

Then Richard Haass, the American diplomat charged with chairing the inter-party talks on unresolved issues in the Six Counties, waded into matters vexillological when he wrote to party leaders seeking their views on the possibility of a new flag for Northern Ireland. (more…)

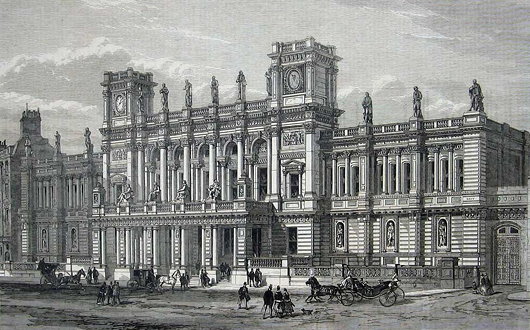

No. 6, Burlington Gardens

Sir James Pennethorne’s University of London

German university buildings are an (admittedly unusual) obsession of mine, and I’ve often thought that No. 6 Burlington Gardens is London’s closest answer to your typical nineteenth-century Teutonic academy’s Hauptgebäude. And the connection is appropriate enough, as No. 6 was built in 1867-1870 for the University of London in what had once been the back garden of Burlington House (which at the same time became home to the Royal Academy of Arts). Despite the building’s Germanic form, the architect Sir James Pennethorne decorated the structure in Italianate detail, providing the University with a lecture theatre, examination halls, and a head office. Pennethorne died just a year after drafting this design, and his fellow architects described it as his “most complete and most successful design”.

The University of London was founded as a federal entity in 1836 to grant degrees to the students of the secularist, free-thinking University College and its rival, the Anglican royalist King’s College. It now is composed of eighteen colleges, ten institutes, and a number of other ‘central bodies’, with over 135,000 students.

Since its founding, the University had been dependent upon the government’s purse for funding, as well as for housing. Accomodation was provided in Somerset House, then Marlborough House, before evacuating to temporary quarters in Burlington House and elsewhere. It was not until the 1860s that Parliament approved the appropriate grant for a purpose-built home for the University to be erected in the rear garden of Burlington House. (more…)

The Lady Altar

The Oratory Church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary,

Brompton Road, London

In the south transept of the Brompton Oratory is the altar dedicated to the Blessed Virgin, perhaps the finest altar in the entire church. It is a favourite place for getting in a few prayers and offering a candle or two or three or four. At the end of Solemn Vespers & Benediction on Sunday afternoon (above) it is where the Prayer for England is said and the Marian antiphon sung.

The Lady Altar was designed and built in 1693 by Francesco Corbarelli of Florence and his sons Domenico and Antonio and for nearly two centuries stood in the Chapel of the Rosary in the Church of St Dominic in Brescia. That church was demolished in 1883, and the London Congregation of the Oratory purchased the altar two years beforehand for £1,550.

The statue of Our Lady of Victories holding the Holy Child had previously stood in the old Oratory church in King William Street, and the central space of the reredos was slightly modified to house it. The Old and New Worlds are represented in the flanking statues, which are of St Pius V and St Rose of Lima — both by the Venetian late-baroque sculptor Orazio Marinali. The statues of St Dominic and St Catherine of Siena which now rest in niches facing the altar were previously united to it, and are by the Tyrolean Thomas Ruer.

London Lately

From a Pimlico rooftop, Friday afternoon.

At lunch, Friday.

A Saturday Mass in St Wilfrid’s Chapel, the Oratory.

A surprisingly sunny afternoon, yesterday in Ennismore Gardens.

A Rainy Day in Winchester

IT WAS LATE summer, neither particularly warm nor cold, and a bit rainy. I hadn’t seen Nicholas in a while but he wasn’t particularly keen on travelling into London. “Why not meet in Winchester?” he suggested, and, never having been to England’s former capital, I thought it was a good idea. I popped on the tube to Waterloo, got on a train, and in no time at all was in the county town of Hampshire. It’s a humanely size town, admirably located, and most famous for its medieval cathedral.

The thieving Protestants, not content with stealing all the cathedrals we built throughout the width and breadth of the land, highten the insult by charging admission to these former shrines and places of worship. I had arranged to meet Nicholas in the Cathedral, though, and the blighters got a good £6.50 out of me. I had a good wander round, though.

These mortuary chests contain the remains of the Saxon royalty of the kingdom of Wessex and later England.

Norman architecture is woefully underappreciated, and might form a useful style to return to today given its relative simplicity. So much Norman architecture was destroyed and replaced by Gothic during later periods of medieval prosperity, but at Winchester the Norman transepts remain.

William of Waynflete, buried here, was a high-flyer in his day. He was, varyingly, Bishop of Winchester, Headmaster of Winchester College, Provost of Eton, Lord Chancellor of England, and founded Magdalen College, Oxford. Not a bad innings.

Richard Foxe chose a more macabre memorial, but enjoyed similar success in this world: he was Bishop of Exeter, then of Bath & Wells, then of Durham, and finally of Winchester. He was Lord Privy Seal and founded Corpus Christi College at Oxford. Foxe and Erasmus sometimes wrote to eachother, and his elaborate crozier is on display at the Ashmolean.

The tomb of Henry Cardinal Beaufort is my favourite memorial in the cathedral. Beaufort — a Plantagenet — was Dean of Wells, Chancellor of the University of Oxford, Bishop of Lincoln, Lord Chancellor of England, and finally Cardinal Bishop of Winchester. He was a sometime papal legate for Germany, Hungary, and Bohemia, and most famously presided over the trial of St Joan of Arc.

One of the walls was inscribed with graffiti.

The cathedral is also the final resting place for the earthly remains of Hampshire native Jane Austen, but nevermind that.

Tours of the College were available, but we decided to leave it for another visit, and went on a wander in the direction of the Hospital of St Cross.

The Hospital of St Cross and Almshouse of Noble Poverty is the oldest charitable institution in England and the largest medieval almshouse. The church could be a small cathedral in and of itself, but as we arrived an interment was taking place, so we thought it best that it, too, was left for another day.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

- American Exuberant February 10, 2025

- Crux Alba Journal Launch February 10, 2025

- The Year in Film: 2024 February 10, 2025

- Articles of Note: 27 January 2025 January 27, 2025

Most Recent Comments

- on When an American aristocrat meets a European Grand Duke

- on The Year in Film: 2024

- on Jesuit Gothic

- on The Borough Synagogue

- on No. 82, Eaton Square

- on Christ Church

- on The Last Will and Testament of Louis XVI

- on Amsterdam

- on Season’s Greetings from the Seventh

- on Season’s Greetings from the Seventh

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories