Great Britain

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Spooks’ Crown

The Security Service, better known as “MI5” has changed its badge to incorporate the change from the St Edward’s Crown to the Tudor Crown that King Charles III has adopted.

The badge was designed by Lt-Col Rodney Dennys who himself had worked for the Security Service’s more glamorous rival, the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6). Dennys had started out in the intelligence game at the Foreign Office and was posted to the Hague before the war. When the Germans rolled in he was on one of the last boats to make it to Britain.

The MI5 emblem was approved by Garter King of Arms in 1981 but (like MI6) the Security Service was still so secret that it did not officially exist, so it was added to the secret roll of arms kept under lock and key in the depth of the heralds’ college in the City of London.

In 1993, after the Service’s existence was formally acknowledged, the badge became known and a flag bearing it often flies from the top of Thames House.

GCHQ has likewise adopted the Tudor Crown, but SIS has not publicly acknowledged any official emblem. (Perhaps it has its own entry in the heralds’ secret roll?) As such, MI6 uses a government version of the royal coat of arms, but theirs has yet to swap crowns.

Silver Jubilee

The Critic invited me to put together a few musings on the aesthetic, economic, and political impact of the JLE and the fundamentally Conservative vision that drove it. You can read it here:

■ The Half-Forgotten Promise of the Jubilee Line

Since it went up this morning, I received a kind email from Tom Newton, son of the late Sir Wilfred Newton who (as you can read in my piece) envisioned and managed the project:

You may be interested that as a family we well remember his intense frustration with the government of the time when they tried to cut back the cost of the project by reducing numbers of planned escalators across the new stations – he had to fight tooth and nail to keep the designs intact and indeed offered to resign over the matter and ultimately successfully defended the designs against cuts. He was very firm that he had no intention of building something which suffered the same capacity issues as the Victoria line resulting from similar reductions in capacity required by government during its construction. This was one of the very few times I ever saw him angry about anything.

He developed excellent relationships with railway engineers and architects whilst in Hong Kong and loved being involved in these large scale infrastructure projects – he was made an honorary member of the Royal Academy of Engineers as a result. He loved being involved in the JLE project very much. He was absolutely fascinated in how the engineers managed the risk of tunnelling across London without damaging other lines and keeping Big Ben standing.

He was asked to lead the construction of the new Hong Kong airport but decided it was time he had spent enough time in Hong Kong.

As a director of HSBC he knew Sir Norman Foster well from when he was the architect on the HSBC office building in Hong Kong. However, when he was asked by the HSBC board to oversee the building of the Canary Wharf office with Sir Norman as the architect, he was asked by the board to make sure Sir Norman was kept on a very tight leash on this build after the massive cost overruns on the Hong King building.

As regards the canopy at the JLE Canary Wharf station Dad had some robust conversations with Sir Norman about adjusting its design to make sure it would be possible to keep clean.

He always had an extraordinary ability to talk to anyone, cut through to the essentials of anything and take a very principled approach in dealing with people and problems.

Many thanks, Tom, for contributing this closer historical perspective of the Jubilee Line Extension’s construction.

Cambridge

There’s a Dutch vibe to Cambridge that I rather like — but also a lingering Protestant Cromwellianism that I don’t. These two factors are not unconnected, and the highway that once was the North Sea is not so far away.

It is not a bad town. It’s like they took Oxford apart, put it back together again in not quite the same way, and added a lot of Regency infill. Oxford is more mediaeval, Georgian, and neo-mediaeval, whereas Cambridge is mediaeval, Tudor, and Regency.

The Cam is slower, quieter, and more peaceful than the Isis, which again gives it the quality of a Hollandic canal. I suspect the punting is better — or at least easier — here than at Oxford.

And of course it is rather more spacious than Oxford, which is hemmed in by geography in a way that Cambridge isn’t.

But it is also eerily quieter. A smart restaurant on a Thursday night was dead by half ten, and the staff refused our plaintive request for a second round of Tokay. (Protestantism.)

Taken on Trust

There is much talk these days of the nature of “high trust” societies and the many benefits which they bring, or once brought in the case of countries like Great Britain that, until relatively recently, fell into this category.

The young Lee Kuan Yew (1923-2015) was astounded when he exited the Underground station at Piccadilly Circus and saw a pile of newspapers and a box of coins and notes, with passers-by being trusted to pay for their own newspaper and calculate their own change. He determined that Singapore must emulate the high trust society that Britons had inherited.

In his excellent book, Britain Against Napoleon: The Organization of Victory 1793-1815, about the logistics of Britain’s fight against Old Boney, Roger Knight writes of how much trade and agriculture across Great Britain relied upon this trust.

Drovers, for example, would take on thousands of pounds worth of animals — pigs, cattle, etc. — from farmers to drive down to London en masse, not returning for weeks, and usually with little or no paper record.

Citing Bonser’s The Drovers: Who They Were and How They Went, An Epic of the English Countryside, Knight relays the following story:

Perhaps the most impressive demonstration of trust was the tradition of dogs being sent home to Scotland or Wales from London on their own. One story involved a Welsh dog named Carlo who journeyed all the way back to Wales from Kent. His owner sold the pony that he had ridden on the outward journey, intending to go home by coach. He fastened the pony’s harness to the dog’s back and attached a note to it, addressed to each of the inns on the route they had followed, to request food and shelter for the dog, to be repaid on a subsequent journey. Carlo reached home in Wales alone in a week.

Even dogs benefited from a high-trust society.

Regnum, Ecclesia, Studium

The threefold division of the world

As such he might be expected to have ideas about the idea of a university, and he wrote about them in The Spectator in August 1983.

Mister Grimond (as he still was then, only just), suggested those interested in the subject “might turn to a lecture by Ronald Cant, sometime Reader in Scottish History in the University of St Andrews”:

[…]

A vital aspect of this tripartite organisation, as Cant says, was that each should serve and support the other. But the studium, while interacting with the regnum and ecclesia, must maintain its independence.

It was certainly the business of the studium to advance knowledge, but that was not to be the end of the matter. Knowledge was linked to public service. The learned man had a duty to the community as well as a right to pursue his intellectual quarry. In fact he pursued the quarry on behalf of the community.

The tripartite division of the world, although old-fashioned, seems to me a useful concept, emphasising that government, morality, and higher education are separate but intertwined.

It seems to me that if we expel the regnum and the ecclesia utterly from the world of the university we shall end up paradoxically with universities totally dependent upon the state… but as subservient as those in Rome.

The liberal spirit gave birth and sustenance to universities; if its progeny does not foster it in the regnum they may indeed end up as purely vocational colleges.

Special Mission to Rome

RELATIONS BETWEEN THE Court of St James’s and the Holy See have evolved in the many centuries since the Henrician usurpation. At times, such as during the Napoleonic unpleasantness, the interests of London and the Vatican were very closely aligned — despite the lack of full formal diplomatic relations. Later in the nineteenth century Lord Odo Russell was assigned to the British legation in Florence but resided at Rome as an unofficial envoy to the Pope.

It wasn’t until 1914 that the United Kingdom sent a formal mission to the Vatican, but this was a unique and un-reciprocated diplomatic endeavour — a full exchange of ambassadors would have to wait until 1982. (Until then, the Pope was represented in London only by an apostolic delegate to the country’s Catholic hierarchy rather than any representative to the Crown and its Government.)

Within a year of the Special Mission to Rome being established, John Duncan Gregory (later appointed CB and CMG) was assigned to it. A diplomat since 1902 who had previously worked in Vienna and Bucharest, he was one of the central figures in the curious ‘Francs Affair’ of 1928, when two British diplomats were believed to have unduly abused their positions to speculate in currency. Despite being cleared of illegality, J.D. Gregory was dismissed from his diplomatic posting — though he was later rehabilitated.

Within a year of the Special Mission to Rome being established, John Duncan Gregory (later appointed CB and CMG) was assigned to it. A diplomat since 1902 who had previously worked in Vienna and Bucharest, he was one of the central figures in the curious ‘Francs Affair’ of 1928, when two British diplomats were believed to have unduly abused their positions to speculate in currency. Despite being cleared of illegality, J.D. Gregory was dismissed from his diplomatic posting — though he was later rehabilitated.

If there are any enthusiasts of the curious subcategory of accoutrement known as the despatch box, J.D. Gregory’s one dating from his time in Rome is currently up for sale from the antiques dealer Gerald Mathias.

It was manufactured by John Peck & Son of Nelson Square, Blackfriars, Southwark — not very far at all from me as it happens. (more…)

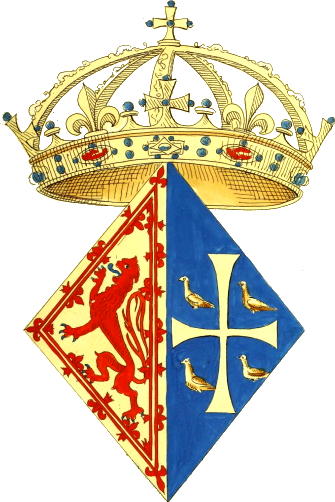

St Margaret Relic Heads to St Andrews

Students from St Andrews University have accompanied their Catholic chaplain to receive a relic of St Margaret of Scotland from the Archbishop of St Andrews & Edinburgh, Dr Leo Cushley.

The relic was put in the care of Canmore, the Catholic chaplaincy at St Andrews, whose chapel is dedicated to the Hungary-born English princess who became Scotland’s saintly queen.

When the relic in St Margaret’s Church in Dunfermline — the country’s royal centre in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries — were being removed from their reliquary the piece of bone fragmented.

The Archdiocese decided to make this an opportunity for the relics of the royal saint to be distributed further.

This relic of St Margaret will remain in Canmore where it will be available for veneration by students and other visitors.

SAINT MARGARET

QUEEN OF SCOTLAND

pray for us

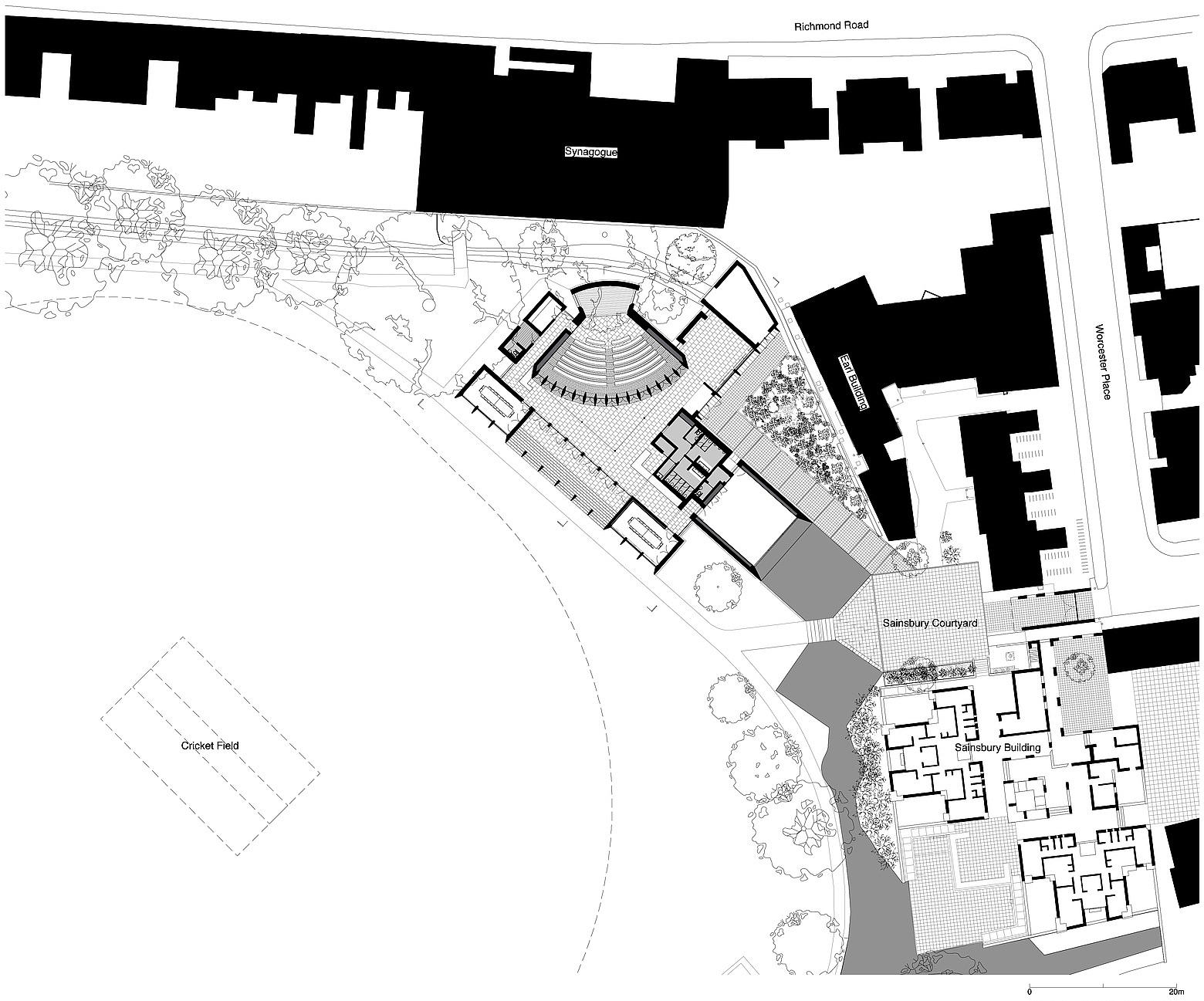

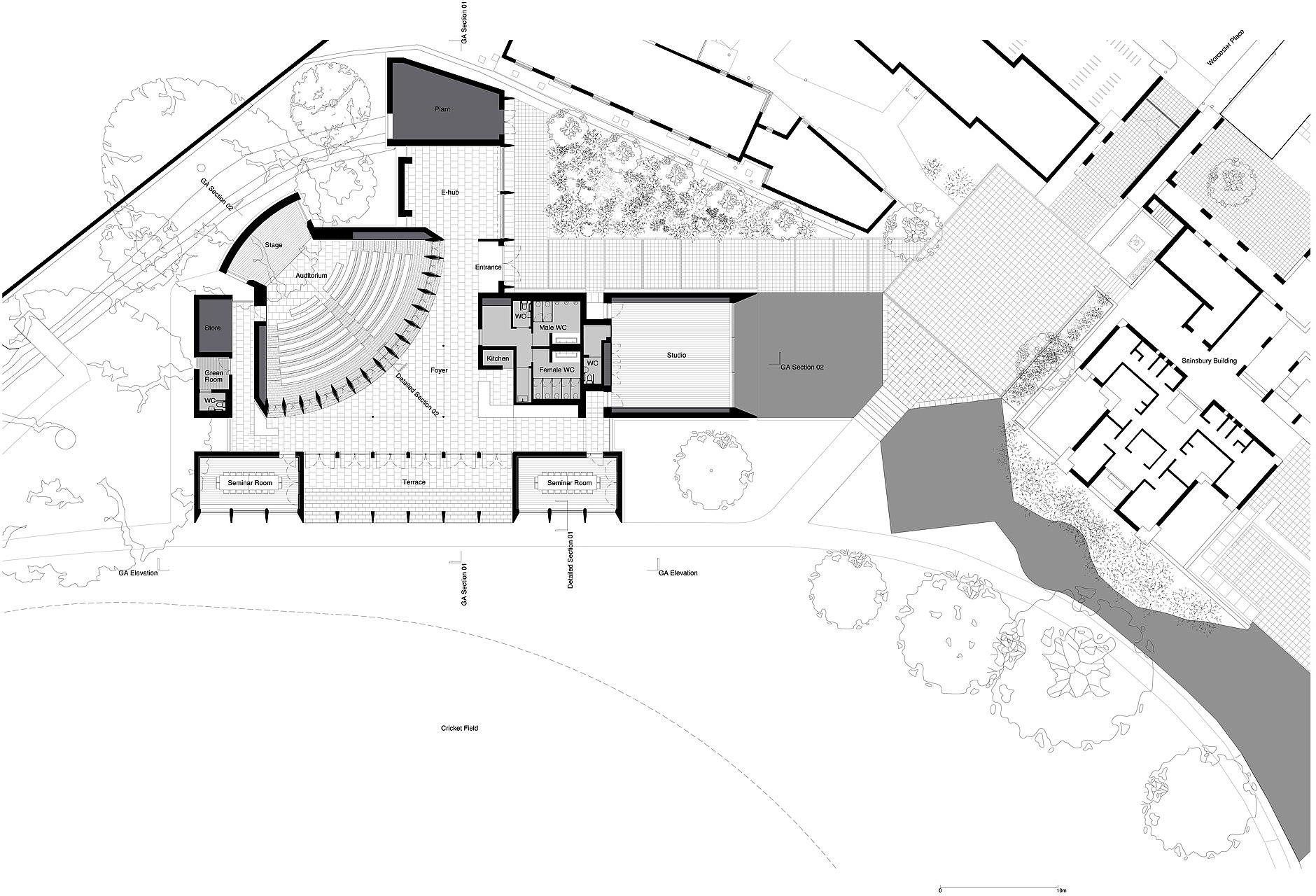

The Sultan Nazrin Shah Centre

Níall McLaughlin Architects at Worcester College, Oxford

WORCESTER is one of the most spacious and scenic of Oxford’s colleges. The classical symmetry of its entrance terminates the view down the gentle curve of Beaumont Street from the Ashmolean Museum. The twenty-six acres of its grounds are pastoral, with lake, gardens, and the broad expanse of a cricket pitch.

Craftily inserted into this arcadia is the Sultan Nazrin Shah Centre designed by Níall McLaughlin Architects. Collegiate work is familiar to this firm, whose new library at Magdalene College, Cambridge, has won them this year’s Stirling Prize, and the Shah Centre provides new useful facilities for the college without giving it the middle finger.

It is named in gratitude to the generosity of an old boy of the college, HRH Nazrin Ali Shah of Perak, who delights in the title of Sultan, Sovereign Ruler, and Head of the Government of Perak, the Abode of Grace, and its dependencies. Judging by the outcome — itself shortlisted for a Stirling Prize in 2018 — I think he spent his money well.

Tempting though it might be to have a gentle wander through the grounds of the college first, the Shah Centre is best approached through the humble entrance lodge nestled in the corner of the L-shaped Worcester Place north of the college.

You are led to a little piazza — the Sainsbury Courtyard — framed by a pair of just-below-foot-level diamond-shaped shallow ponds of Kahn-ian geometry. (They are actually a tiny extension of the college lake.) The broad expanse of cricket pitch beyond, connected by a flat wooden bridge segmenting the two diamond ponds, is alluring. But off at a 45-degree-angle on the right, the entrance to the Shah Centre bids the visitor on.

Beyond the limestone cladding you move indoors to a sea of light-treated oak, in the thin supporting columns of the one-storey entrance hall curving around the arc of the lecture theatre and in the trelliswork ceiling.

To the left, the dance studio looks out onto the pools through three giant panes of floor-to-ceiling glass.

To the right, a small bar can double as a registration desk.

The lecture theatre seats 170 and is accessed through a curve of wooden slats that hide panels that can swing out if closing the space is necessary.

Auditoria with ceilings sloping down toward the stage usually feel cramped but here the ceiling is arranged in sharp corrugations (like the flanges of the Gonbad-e Qabus) which capture the light from the clerestory behind.

The feeling is one of spaciousness: rather than facing downwards they are like rays of the sun reaching outwards and up. Instead of wings offstage, there are tall windows of a single sheet of glass flanking, offering natural side light.

The view from the stage is even better, looking out at the gentle curve of clear windows breaking at near-half-way, dividing the anterior spaces below from the open skies above.

Straight out from the auditorium is the terrace with its steps flowing gently down to the field beyond.

It is from the cricket ground that we get the best view of the Shah Centre. The lines are elegant, and there’s a hint of the better architects from Italy’s fascist era — Pagano or Terragni, not Piacentini. The easy movement of space and light, with a gentle breeze rolling off the green.

The architectural genius of the Oxford college as a type is that it allows for the magnificent to be completed on a humane scale for an intimate community of students, scholars, and academics. Níall McLoughlin’s skill at achieving this in a modern idiom is what makes the accolades he accrues — fickle gifts at the best of times — so justified in his case.

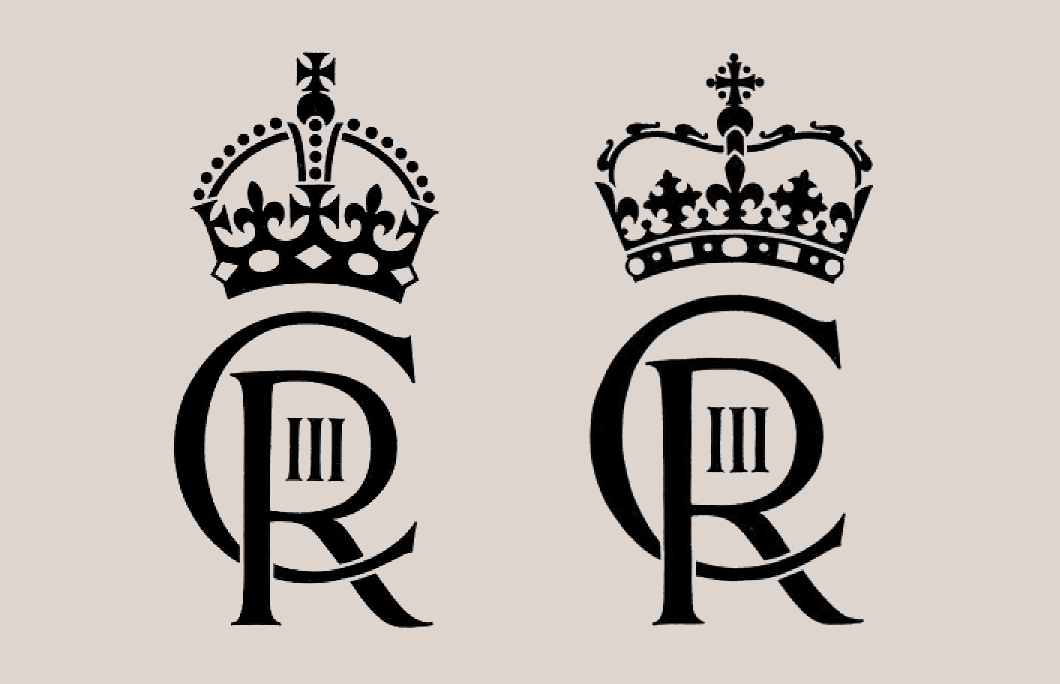

Cypher Shift

Out with the old, in with the new: the King has released his new royal cypher, with a stylised CR III replacing the familiar EIIR. As with so many things, I am sure we will get used to it with time.

Given the longevity of the late Queen’s reign it will be some time before we see it appearing on pillarboxes, but it will enter our lives more quickly via postal franking, stamps, currency, and uniforms.

Many are trying to come up with complex, almost mystical, explanations for why St Edward’s Crown has been replaced with the Tudor crown atop the cypher. More likely, I suspect, is that it is a useful means of giving the new reign a respectful visual differentiation from its preceding one.

I’ve always been rather fond of the Tudor crown, and the Caledonian version of the new cypher rightly includes the Crown of Scotland — the oldest amidst the Crown Jewels of this realm as (unlike England) Scotland was spared the iconoclastic destruction of Cromwell’s republic.

The new royal cypher, left, and its Scottish variant, right.

Elizabeth II

ELIZABETH II

the United Kingdom

of Great Britain & Northern Ireland

Canada

Australia

New Zealand

Jamaica

the Bahamas

Grenada

Papua New Guinea

the Solomon Islands

Tuvalu

Saint Lucia

Saint Vincent & the Grenadines

Antigua & Barbuda

Belize

and Saint Kitts & Nevis

quondam Queen of South Africa, Pakistan, Ceylon, Ghana, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Tanganyika, Trinidad & Tobago, Uganda, Kenya, Malawi, Malta, the Gambia, Guyana, Barbados, Mauritius, and Fiji

Head of the Commonwealth

Defender of the Faith

Duke of Normandy

Duke of Lancaster

Lord of Mann

Head of the House of Windsor

A Home for Bard and Ballet

Sir Basil Spence’s unbuilt Notting Hill theatre

Sir Basil Spence was just about the last (first? only?) British modernist who was any good. His British Embassy in Rome is hated by some but combines a baroque grandeur appropriate to the Eternal City with the crisp brutalism of modernity that makes it true to its time.

In 1963, Spence accepted the commission from the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Ballet Rambert for a London venue to host the performances of both bodies.

The poet, playwright, and theatre manager Ashley Dukes had died in 1959, leaving a site across Ladbroke Road from his tiny Mercury Theatre (in which his wife Marie Rambert’s ballet company performed) for the building of a new hall.

The design moves from the sweeping curve of the street frontage up to a series of angular concoctions and finally the large fly-space above the stage itself.

It made the most of a highly constricted site and would have housed 1,100-1,600 patrons (historical sources vary on this figure). This was a big step up from the old Mercury Theatre which housed 150 at a push.

Ultimately, the plan failed. London County Council was worried there wasn’t enough parking in the area, and the Royal Shakespeare Company was tempted away by the City of London Corporation which was building the Barbican Centre.

Anglo-Gaullist Reading Update

The latest round of news or commentary of Gaullist content or interest:

Mercator: Charles de Gaulle: a wise ruler of France

Financial Times: France invokes the golden age of de Gaulle

Politico: Why all French politicians are Gaullists

Variety: Cliché-Ridden ‘De Gaulle’ is Unworthy of Its Iconic Subject

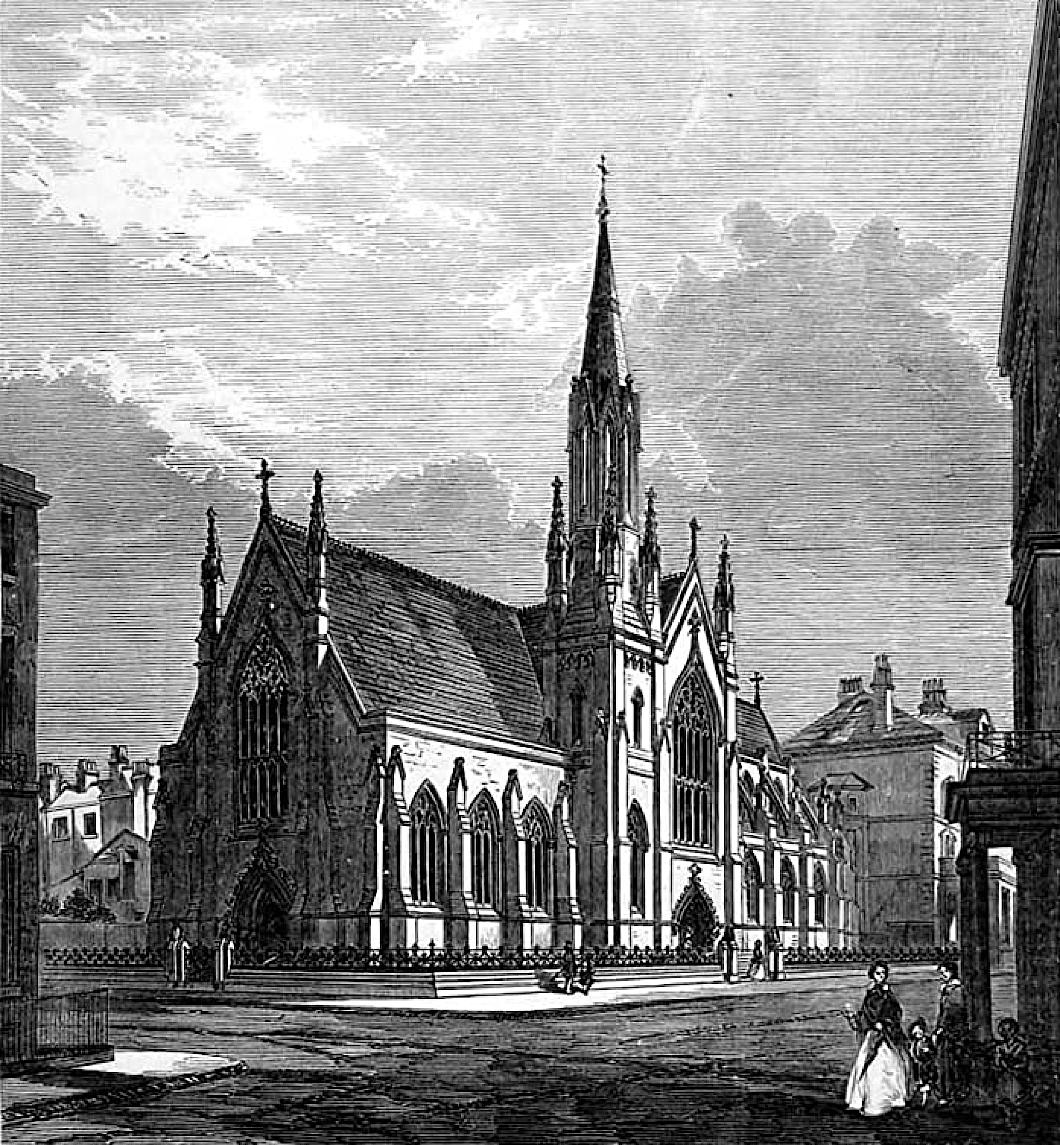

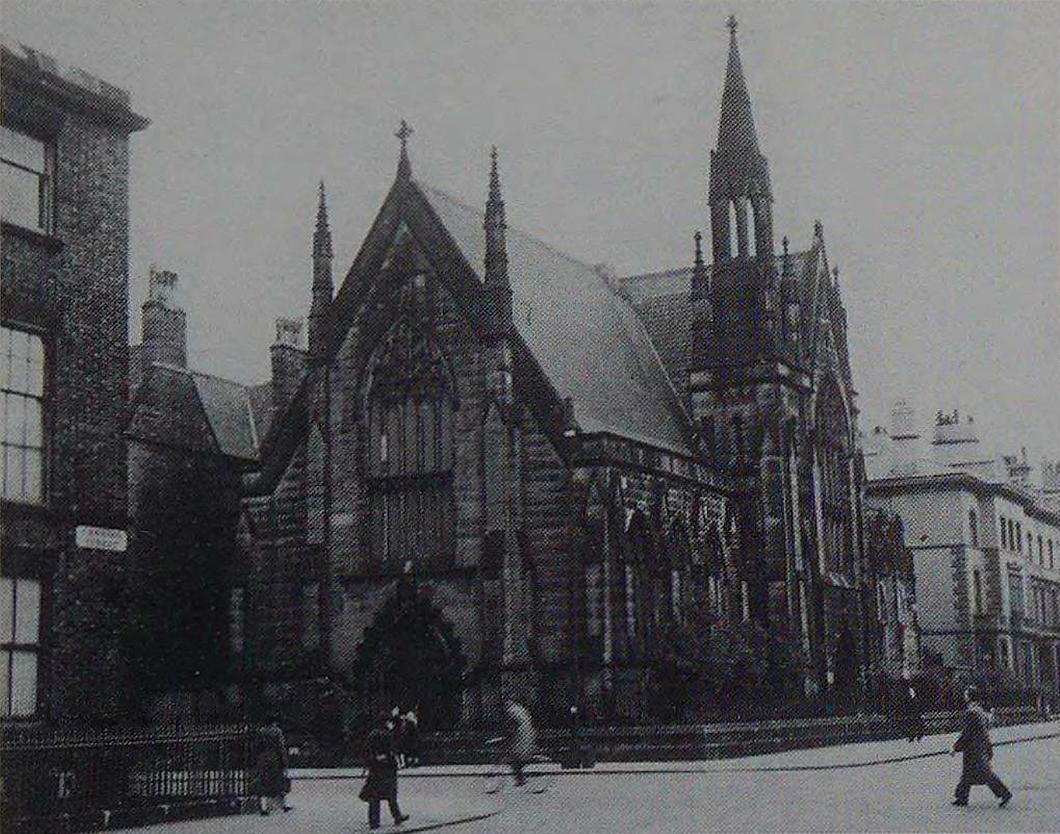

Liverpool’s Irvingite Church

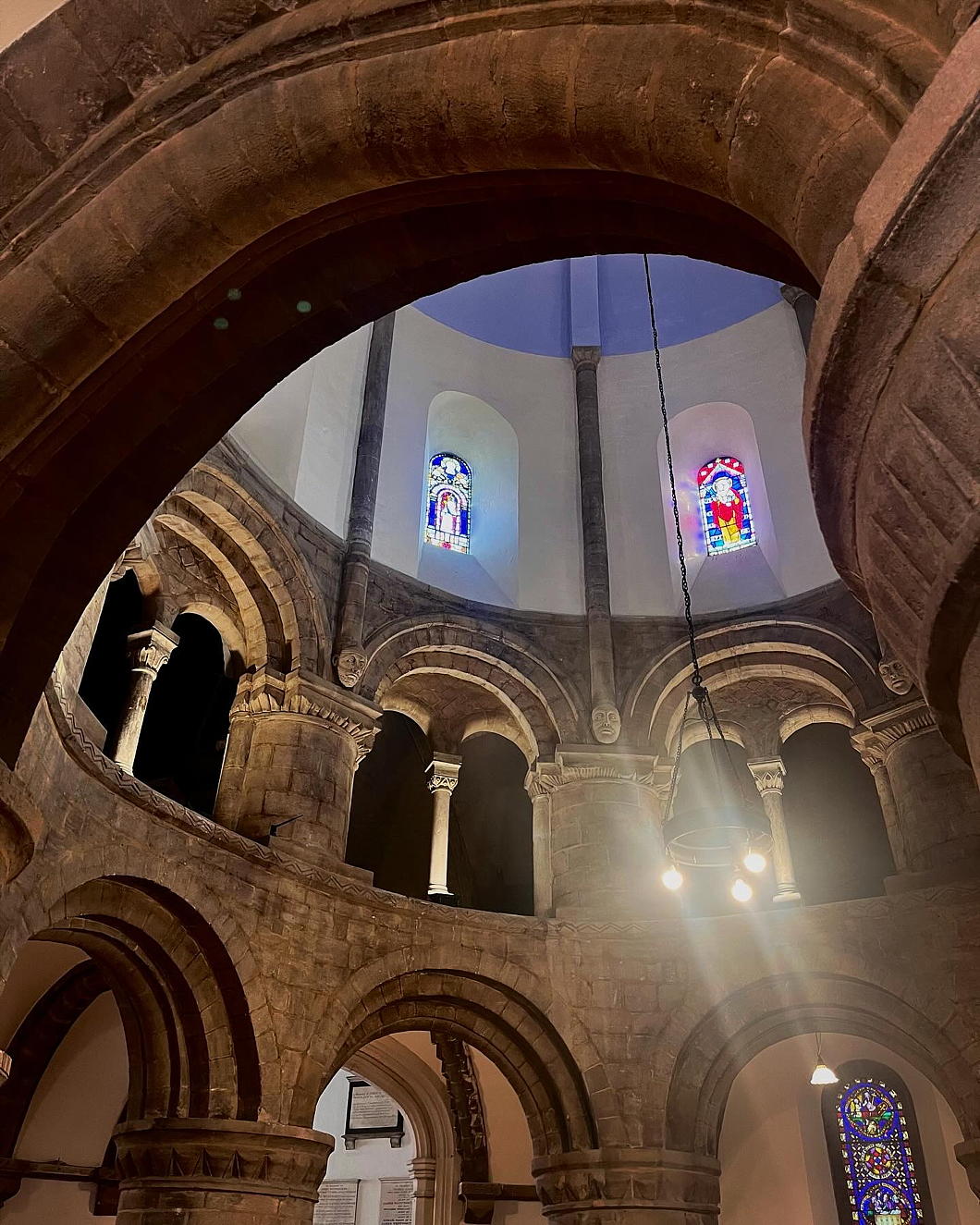

The soi-disant “Catholic Apostolic Church” was one of the strangest but most fascinating Protestant sects the Victorian world brought forth. It was entirely novel — perhaps outright bizarre is a better description — in its combination of millenarian theology, evangelical preaching, and inventive ceremonialism. They were often referred to as Irvingites as a shorthand, owing to their origins amongst the followers of the Rev. Edward Irving, a Church of Scotland minister who led a congregation in Regent Square, London.

The Irvingites — after the death of Irving, it must be said — invented an elaborate hierarchy of twelve “apostles”, under whom served “angels”, “priests”, “elders”, “prophets”, “evangelists”, “pastors”, “deacons”, “sub-deacons”, “acolytes”, “singers”, and “door-keepers”. Coming from a very Protestant, low-church background, they curiously concocted elaborate liturgies influenced by Catholic, Greek, and Anglican forms of worship.

Another unique aspect of this group was its lack of denominational thinking: the Catholic Apostolic Church did not demand any strict or exclusive communion but was happy for its members and supporters to continue to be members of other churches or denominations.

One of the founding “apostles” of the Irvingite Church, Henry Drummond, married his daughter off to Algernon Percy, later the 6th Duke of Northumberland. That duke and his two immediate successors were known to be supporters of the Catholic Apostolic Church without disowning their established Anglican affiliation.

Despite this aristocratic land-owning connection, socially the Irvingite church spread most rapidly amongst the well-to-do mercantile classes, which meant they had congregations in places like Manchester, Birmingham, Liverpool, Edinburgh, and even Hamburg. They were also very strict about tithing, which — combined with their mercantile status — meant they had a fair amount of money to spend on church building.

In Liverpool their church was built on the corner of Canning Street and Catherine Street in 1855-56. The design by architect Enoch Trevor Owen was influenced by Cologne Cathedral, with a nave more than 70 feet high.

Owen later moved to Dublin where he was employed as architect to the Board of Works, though he also designed the Catholic Apostolic Church in that city as well. (Today that building serves as Dublin’s Lutheran Church.) There’s some indication he designed the Catholic Apostolic Church in Manchester, so he might very well have been a member of the sect himself.

Another centrally important fact about the Irvingites: they didn’t believe that their original “apostles” could appoint further apostles. So when the last living “apostle” ordained his last “angel”, no further angels and so forth could be created. It endowed the clergy of this unique branch of Protestantism with an effective end date, but you have to give them credit for sticking with it. The last “apostle” died in 1901, the last “angel” in 1960, and their last “priest” in 1971.

Gone are all their elaborate inventive liturgies, and unsurprisingly the congregations have tended to fade away as well. The last clergy often recommended the lay people in their charge attend Church of England services when their own services stopped. The body continues to exist, and beside paying for the maintenance of its properties also makes annual grants to mostly Anglican but also Catholic and Eastern Orthodox bodies. In some very rare places, like Little Venice, prayer services are still held.

Indeed they still own their great central church in Gordon Square in Bloomsbury, though its chief use in the past decades has been being rented out first to an Anglican university chaplaincy, and now to the use of High-Church Anglicans as well as an Anglican evangelical mission.

In Liverpool their church was given Grade II listing protection in 1978, possibly when prayers services were still being held. By 1982 the church was up for sale, but without a buyer it succumbed to a fire in 1986.

The church lingered in ruins until the late 1990s when it was demolished and a nondescript block of flats erected on the site.

Elsewhere: Liverpool: Then and Now | Velvet Hummingbee

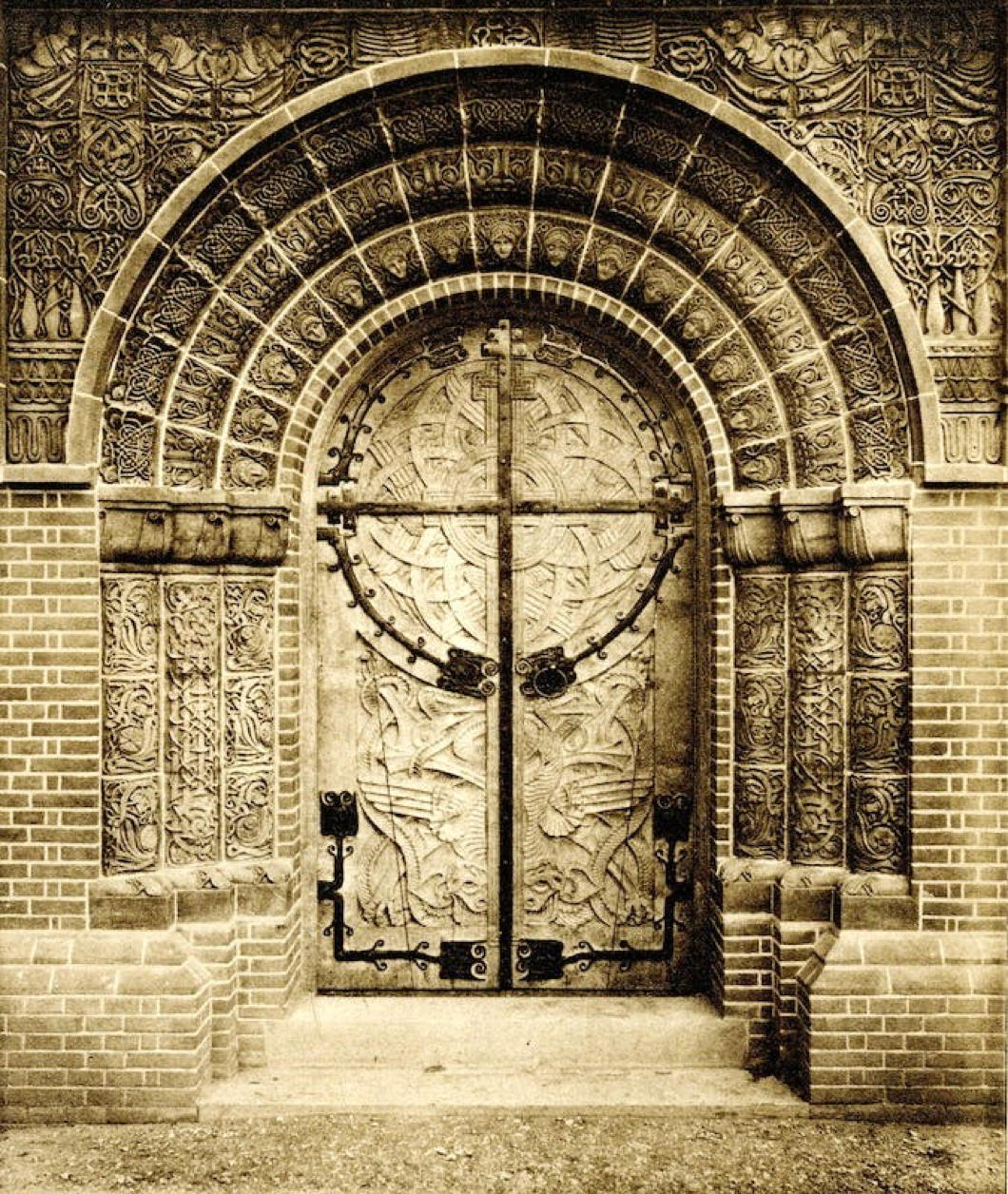

Watts Chapel

IS THIS the most beautiful door in England? The Watts Chapel in the village cemetery of Compton in Surrey is certainly one of the most remarkable buildings in the land.

I have to admit it completely escaped my notice until a friend of mine founded a distillery a few years ago and based the logo on the seraphs depicted within the chapel. While the interior is indescribable it is also curiously incapable of being captured by photography to any satisfactory degree.

Being a Celt with a Norman surname who loves the Romanesque, it’s the entry portal that captures my imagination. It beams at the very same frequency as my heart.

What a wonderful melange of elements — Celtic, Saxon, Romanesque, and Nordic — are combined here with blithe ease.

Incessant stylistic purity is the realm of the boorishly tiresome, as Ninian Comper knew well, and here the eclectic blend works well.

As architects are incapable of learning the proportion required by Georgian and neo-classical styles, I’ve long believed the Romanesque (or ‘Norman’ as the English often call it) must be the starting point for the recovery of good solid modern architecture.

I, for one, welcome our Norman-Romanesque future with open arms — while prizing this late Victorian gem.

Fifth Republic Britain

An Anglo-Gaullist Reading Round-up

While I’m a big Adenauer fan there’s little doubt that de Gaulle was the greatest European statesman of the twentieth century and an historical figure of such a position will always be the subject of interest.

Both Jonathan Fenby’s 2010 book The General: Charles de Gaulle and the France He Saved and Dr Sudhir Hazareesingh’s 2012 In the Shadow of the General: Modern France and the Myth of de Gaulle received wide notice, but neither as much as Julian Jackson’s 2019 A Certain Idea of France: The Life of Charles de Gaulle.

Jackson’s work is indeed magisterial and Lord Sumption’s praise of it as “the best biography of de Gaulle in any language” is only just an exaggeration. (For a strong bibliography of works on the general, see the appendix of Charles Williams’s 1993 The Last Great Frenchman: A Life of General de Gaulle.)

Study of the life and contradictions of de Gaulle is always worthwhile, but many spy a Gaullist moment in the Tory party’s refreshingly surprising turn away from ideological liberalism towards a more pragmatic conservatism under Boris Johnson.

Painting Johnson as Britain’s first Gaullist prime minister would be a stretch, but there is certainly some crossover: nationalist, economically interventionist, focused on national sovereignty and national exceptionalism.

■ Eliot Wilson pointed out this summer that Boris has always been difficult to classify in ideological terms.

■ Speccie political editor James Forsyth wrote in The Times that Boris the Gaullist puts action over ideas. Just before the party conference Forsyth also predicted the PM’s speech would be “in line with his recent Gaullist turn”.

■ QMUL’s Nick Barlow explores the parallels between de Gaulle’s Fifth Republic and Boris’s style of government.

■ Meanwhile Aris Roussinos argues that de Gaulle was always right in vetoing British entry into the EEC, and that true-blue FBPE types should welcome Brexit as advancing the cause of European integration.

■ Dean Godson (New Statesman) says that Defence Secretary Ben Wallace is pursuing “almost Gaullist trajectory for future British policy”.

■ When asked (on GB News) where he sits on the political spectrum, national treasure Peter Hitchens expressed his surprise that the Gaullist combination of “strong defence, patriotism, a strong welfare state, and national independence” isn’t more common in British politics.

■ ‘Bagehot’, the political column in The Economist, put it that the man who rebuilt post-war France has some important lessons for Britain’s prime minister: What Boris could learn from de Gaulle.

■ The American Conservative embarrassingly illustrated a piece on Europe’s Gaullist Revival with a picture of General Kœnig. (Always check the képi — as a brigadier general, de Gaulle only had two stars!)

■ Mike Bird discerned some Anglo-Gaullism in a pile of recent newspaper headlines.

■ As long ago as 2017 — what a world away that was! — Prospect argued in a somewhat rambling piece that the Brexiteers were Britain’s new Gaullists.

■ Honourable mention: Frederick Studemann chides Churchill and dumps de Gaulle, saying Boris should model himself on Bismarck and make for a Prussian Brexit.

But, for all this, when New Labour bigwig John McTernan suggested that Boris is not a Churchill but a de Gaulle, the great Julian Jackson himself pointed out there are still great differences between the PM and le général.

All the same, I’m welcoming our Anglo-Gaullist future with open arms.

Staats Long Morris

Everyone knows about Gouverneur Morris, scion of one of New York’s great landowning families and given the moniker ‘penman of the Constitution’. As a signer of the Declaration of Independence his half-brother Lewis Morris III was a fellow ‘founding father’. Less well-remembered is his other half-brother Staats Long Morris (1728–1800).

Their father Lewis Morris II was the second lord of Morrisania, the feudal manor that covered most of what is now the South Bronx and has given its name to the smaller eponymous neighbourhood today.

Staats and Gouveneur owe their distinctive Christian names to the family names of their respective mothers.

Lewis II married Katrintje Staats who provided him with four children. After Katrintje died in 1730, Lewis married Sarah Gouverneur, daughter of the Amsterdam-born Isaac Gouverneur. Sarah’s uncle Abraham was Speaker of the General Assembly of the Province of New York, a role Lewis Morris II eventually filled.

Staats was born at Morrisania on 27 August 1728 and studied at Yale College in neighbouring Connecticut as well as serving as a lieutenant in New York’s provincial militia. He switched to the regular forces in 1755 when he obtained a commission as captain in the 50th Regiment of Foot, moving to the 36th in 1756.

Around that time Catherine, Duchess of Gordon, the somewhat eccentric widow of the third duke, was on the lookout for a second husband and Staats — though American, mere gentry, and ten years her junior — met with her approval. They were married in 1756 and Staats moved in to Gordon Castle to live as the Dowager Duchess’s husband.

‘He conducted himself in this new exaltation with so much moderation, affability, and friendship,’ a newspaper reported in 1781, ‘that the family soon forgot the degradation the Duchess had been guilty of by such a connexion, and received her spouse into their perfect favour and esteem.’

With the Duchess’s patronage, Lieutenant-Colonel Staats raised the 89th Regiment of Foot — “Morris’s Highlanders” — from the Scottish counties of Aberdeenshire and Banffshire though she was extremely cross when her new husband’s regiment was despatched to India where it took part in the siege of Pondichery.

In the event, Morris delayed following his regiment to India, leaving England in April 1762 and remaining there only until December 1763. When the young fourth Duke of Gordon came of age the following year, Staats turned his eyes to America and engaged in land speculation there. In 1768 he and the Duchess even went to visit their purchases in the new world, returning to Scotland in the summer of the following year.

With the fourth Duke’s help, and on the eve of the revolutionary stirrings in North America, Staats was elected to the British parliament for the Scottish seat of Elgin Burghs in 1774. He managed to hold on to it for the next ten years. Was this New Yorker the first Yale man to be elected to Parliament? I can’t find any before him, but more thorough research might prove fruitful.

In 1786 he inherited the manor of Morrisania but with the intervening separation between Great Britain and most of her Atlantic colonies General Morris thought it best to sell it on to his brother Gouverneur.

Though he had rejected a future in the world into which he had been born, Staats did return to North America in a professional capacity in 1797 when he was appointed governor of the military garrison at Quebec in what by then was Lower Canada.

Morris died there in January 1800, but his earthly remains were sent back to Britain where he was interred in Westminster Abbey — the only American to receive that honour.

Articles of Note: 23.XI.2020

• France’s Year of de Gaulle has marked the fiftieth anniversary of his death earlier this month and what would have been the general’s one-hundred-and-thirtieth birthday yesterday. Julien Nourian has put together a Weberian analysis of the general and his charismatic mystique.

• President Trump is a very different kind of leader to de Gaulle, and his chances of continuing in the White House are not looking great at the moment. (Our head of legal in New York thinks he’s still got a chance, however.)

Regardless of who will be inaugurated in January of next year, Trump managed to win the highest proportion of minority votes of any Republican candidate since 1960 (when the GOP choice was a member of the NAACP). Meanwhile, Trump lost votes among old, white, well-to-do men.

What is the future of American political conservatism? Ben Hachten points out It’s Not Your Father’s GOP.

New England poli-sci professor Darel E. Paul explores The Future of Conservative Populism, pointing out the big increase in the Hispanic vote for Trump — especially Hispanics living in Texas along the Mexican border.

• In Britain, Ferdie Rous says the Conservative party is having difficulty reconciling the business wing of the party with our rural roots, but suggests that The writings of Lewis and Tolkien embody conservative environmentalism.

Meanwhile David Skelton asserts It was working class voters who delivered this majority – and Johnson must not abandon them now.

• Here in London we’re still in the middle of the second lockdown. Instead of following the science, governments around the world are implementing the exact opposite of effective measures to combat the pandemic. It’s The Greatest Scandal of Our Lifetime according to R.J. Quinn.

• We can always do a with a dose of Metternich and Wolfram Siemann’s 900-page doorstop has provided a chance for many to analyse the master diplomat. Ferdinand Mount examines The Prime Minister of the World.

• And finally, the Museum of Literature Ireland features an online exhibition on the American writer, speaker, reformer, and statesman Frederick Douglass’s visit to Ireland 175 years ago. (Available as Gaeilge too.)

F.X. Velarde: Forgotten & Found

Many of the architects of the “other modern” in architecture were forgotten or at least neglected once the craft moved in a more avant-garde direction.

The British Expressionist architect F.X. Velarde who produced a number of Catholic churches in and around Liverpool in the interwar period and beyond is the subject of a new book from Dominic Wilkinson and Andrew Crompton.

There will be a free online lecture tomorrow on ‘The Churches of F. X. Velarde’ given by Mr Wilkinson, Principal Lecturer in Architecture Liverpool John Moores University. Further details are available here.

The book is available from Liverpool University Press with a 25% discount through the Twentieth Century Society. (more…)

Turn the Ship Around

The UK’s Supreme Court is a nine-year experiment that has failed

If you open the hood of your car and mess about with the engine you can hardly be surprised if, later, it stops working at just the wrong moment. Likewise, constitutions by their very nature ought not to be fiddled with, and the current crisis in Westminster is ample proof.

Under the old system – before the Supreme Court and Fixed Term Parliaments Act – there would have been no crisis at all. The Prime Minister would see there is no working majority in favour of any way forward and would simply call a general election. Hypothetically, this would result in a government with a majority capable of moving business forward – all without much controversy.

Since FTPA was passed, however, the PM now needs a two-thirds majority in Parliament in order to bring about an election and the Opposition has up to this point blocked any chance at referring to the electorate in fear that the voters will back Boris over Corbyn. At the time it was passed, proponents argued not much would change with FTPA, as the point of the Opposition is to try and become the Government and what Opposition in its right mind would ever turn down the chance to fight a general election at a moment of crisis?

Enter now the Supreme Court in a timely intervention over the Prime Minister’s decision to end the longest parliamentary session on record by advising the Queen to prorogue Parliament over the long-planned conference recess. The Court has only been in operation since 2009, when it was created because legal experts and constitutional gurus told us it wasn’t correct for the highest court of appeal to technically be part of the legislature (even though this practice had been ratified by centuries of experience and had failed to present any difficulties).

The old system was robust and flexible; it is the innovation which has created stasis. Before it bent: now it breaks. Britain’s unwritten constitution is often summarised as “The Crown-in-Parliament is Supreme”. That means the Government exercises power with the authority of the Sovereign under the scrutiny of and with the confidence of Parliament. With the final court of appeal removed from the Parliament, where did that leave the Supreme Court? The justices have sought to answer with a judgement asserting that they are the ultimate authority in the land, supreme even over the exercise of the Royal Prerogative.

This runs contrary to the entire thrust of the UK’s constitutional development, which – up until this point – has been to strengthen scrutiny of the exercise of power and to increase the accountability of those who exercise that power. The Supreme Court’s judgement is a massive expansion of the justices’ own power without any counterbalancing accountability. When the Prime Minister exercises power he is held accountable by his need to maintain the confidence of his party colleagues and of the House of Commons. If he fails to do so he can be replaced as PM or ultimately his party can be chucked out by voters in a general election. How are Supreme Court justices to be held accountable though? What actions can voters take when justices overstep the bounds?

If justices seek to exercise political power than they must face concomitant levels of scrutiny and accountability that don’t – yet – exist. They cannot expect to receive the traditional obeisance and deference of politicians and the general public that the pre-Supreme Court judiciary received if they fail to observe the same self-restraint and respect for the Parliament’s role as legislature that the pre-Supreme Court judiciary observed.

The fundamental question is what the appropriate reaction of an ordered society is when judges overstep their bounds. If a Conservative majority government – presuming that is even the result of the next election – fails to respond appropriately to the Supreme Court’s ruling it is difficult to see how the UK can avoid going down the American route of a highly politicised judiciary. Ultimately, this would mean greater parliamentary oversight in the appointment of justices to the Supreme Court. Would they be prepared for long hearings in parliamentary committee rooms where every aspect of their past (including their student antics at university) were dredged before the public? Would voters be prepared to accept that an unaccountable Supreme Court can overturn any action of a democratically accountable executive or law passed by a democratically elected parliament with which the justices disagreed?

A Conservative majority government could easily, by simple Act of Parliament, remove the Royal Prerogative from the purview of the Supreme Court and further clarify (meaning restrict) the Court’s room for manoeuvre. But perhaps this isn’t a problem that can be fixed by tweaking. Trying to make sure justices understand they don’t have the authority to make naked power grabs seems impossible when you have an establishment that, in legal circles and otherwise, believes its will overrides the democratic mandate of the people in a constitutional monarchy. Restrictive legislation can help clarify, but it won’t strike at the heart of the institutional cockiness the Supreme Court exudes. (Remember that it ominously chose the Greek letter omega – symbolising finality – as its official emblem.)

Far better, then, to concede our own humility and accept that the Supreme Court has been a nine-year experiment which has failed. This would mean repealing those provisions of the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 which created Supreme Court in 2009 and going back to having Lords of Appeal in Ordinary sitting as the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords. There would be no problem with Law Lords continuing to sit in Middlesex Guildhall across Parliament Square as the Supreme Court does today.

Opponents must accept that the unaccountability the Supreme Court seeks to exercise belongs to another era: we live in the age of transparency, accountability, and taking back control.

History is littered with coups and grabs for power. Some succeed, others are attempted and fail. This “constitutional coup” can be foiled, but it requires a general election, a Conservative majority, and a government intent upon deliberate action.

Lady Day

Today is Lady Day, the Feast of the Annunciation when the Archangel Gabriel appeared to the Blessed Virgin Mary and announced that she would conceive and bear the child Jesus.

The angelic salutation – “Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee… Blessed art thou amongst women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus” – forms the basis of the Ave Maria, one of the most widely uttered prayers in Christendom.

Traditionally this has been one of the greatest of devotions to the Virgin amongst the English, which is why there are so many pubs across England named ‘The Salutation’.

For centuries in England and Scotland (as well as elsewhere), Lady Day was the first day of the calendar year. Scotland moved this to 1 January in 1600 and England did likewise in 1750.

Nonetheless, the English tax year is still based on this date as it commences on 6 April, which is the Annunciation plus twelve days to mark the difference between the old Julian calendar and the modern Gregorian one.

In the realms of fiction, 25 March is the day Tolkien chose for when Frodo destroyed the Ring in Mount Doom, securing the fall of Sauron – with obvious parallels to Christ’s Incarnation securing the defeat of Satan.

This stained glass roundel above is not English, however, but from the Southern Netherlands around 1500-1510.

Elsewhere, A Clerk of Oxford has a good section on the Annunciation.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Articles of Note: 27 January 2025 January 27, 2025

- Spooks’ Crown January 23, 2025

- Jesuit Gothic January 23, 2025

- Christ Church December 29, 2024

- A Christmas Gift from the Governor December 24, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories