Germany

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Potsdam’s City Palace to be Resurrected

THE OLD STADTSCHLOSS of Potsdam, destroyed by aerial bombing during the Second World War, will rise again next to the Old Market in the Brandenburg capital. The provincial government has decided to rebuild the old Stadtschloss to serve as a home for the Landtag, Brandenburg’s provincial parliament. While it was first conceived of building a modern building on the site, or having some reconstructed façades and others modern, a €20-million donation from the software entrepreneur Hasso Plattner has ensured the façades and massing of the building will follow the outline of the old stadtschloss. The interiors will be simple and modern, and to keep the costs down, much of the finer Baroque detailing of the façades will not be included. “I hope,” Herr Plattner said, “that the necessary compromises do not diminish the great impression overall.” (more…)

The Internal Exile of the Saar

At the beginning of Hitler’s rule, many patriotic German anti-Hitlerites fled to the Saarland, which was Germany but still under French occupation. In a bizarre state of internal exile, anti-Nazi publications, be they Christian, Nationalist, Communist, or Jewish flourished for a very brief period. One of these journals was Das Reich, founded by Hubertus Prinz zu Löwenstein, who (if I recall my personal studies from St Andrews years properly) was a bit of a rogue in his own way, sympathizing with the Red forces during the Spanish Civil War.

A plebiscite on rejoining the Saarland with Germany proper had been scheduled before Hitler’s rise to power (just like the lamentable award of the 1936 Olympics to Berlin, though they turned out to be some of the most influential and well-run games to date) and, while the inhabitants were no keen Hitlerites, they had naturally tired of French occupation and duly voted to kick the French out. Right result, but very poor timing.

The anti-Hitlerites had to flee further, to Paris (where Pariser Tageblatt and later Pariser Tageszeitung were founded), London, and New York. German Jews sometimes fled as far as Shanghai where the English-language Shanghai Jewish Chronicle began a German edition in response to the influx. (There are some interesting stories about Shanghai Jews, and of course the famous newspaper-owning family of Jewish converts to Catholicism in Shanghai, but they’ll have to wait for another day).

The Messiah in the Sportpalast

The following feuilleton was written before Hitler became the master of Germany. The scene is the Berlin Sportpalast, the largest indoor arena in the world when it opened in 1910 and, at this time, the setting for the rallies of the various political parties vying for control of the Weimar Republic.

On the night of the Horst Wessel commemoration Hitler speaks in the Berlin Sportpalast. People who have neither seen nor heard him will perhaps never fully understand the significance of the profoundly ominous mind-set that has developed in Germany since the war. The reality — Hitler’s version of reality and its full implications — goes far beyond anything you might read in the newspapers, or imagine. Here is that reality, drawn from the life. (more…)

How “New Yorker” is the Staats-Zeitung?

When I was a youngin’, one of the joys of Sundays was the trip to the bakery and the newsagent after church. A vast array of newspapers was on hand for perusal while Pop nipped into Topps Bakery next door. We usually only bought The European, but I browsed everything on hand. One of the available titles was the New-Yorker Staats-Zeitung, founded in 1834, and the oldest German newspaper in the New World. The “Staats” was daily from 1854 until 1953, when it went weekly. In the late 1930s, the circulation was about 80,000, falling to 25,000 in the late 1990s, and stands around 10,000 today. It seems a pity that this “New York” newspaper is now edited from Sarasota, Florida instead of from Manhattan, but at least the Staats-Zeitung survives.

A Wanderer Anecdote

“It’s too easy for theological writers to sling around Abstractions with Capital Letters, as if with each stroke of the pen they’re tapping into Plato’s realm of changeless, ineffable Forms. Or at least that they’re writing in German, where all nouns start with caps.”

So begins John Zmirak, who tells a delightful story about one of America’s premier Catholic newspapers.

“A friend of mine used to write weekly for the estimable investigatory journal The Wanderer. Founded by German-Catholic immigrants, it was published auf Deutsch well into the twentieth century.

As my friend recalled, ‘The editors were, I think, waiting for the rest of the country to catch up with them. At last they admitted that this was unlikely, and agreed to translate the paper. But they kept on as their typesetter someone named Uncle Otto, who for years insisted on capitalizing every noun.’”

The Freiherr of Finance

Germany’s new finance minister, Freiherr zu Guttenberg & his wife, Freifrau Stephanie.

Unmentioned by this editorial is that Baron zu Guttenberg’s grandfather (his mother’s father) was the late German winemaker & Croatian politician the Count of Vukovar. From the Count, Baron zu Guttenberg is descended from the noble house of Eltz, who are responsible for one of my favourite castles in the whole world, Burg Eltz, which once graced the 500-deutschmark note.

At the ripe age of 70, the Count of Vukovar took up arms in defence of the town of Vukovar during the Yugoslav Wars of 1991. The Count was elected to the Croatian parliament the following year as an independent, and served in that body until 1999, when he retired from politics. Nonetheless, the Croatian parliament persuaded him to accept honourary membership of parliament in his own right, in which role he continued until his death in 2006.

The Baron’s wife, meanwhile, is Stephanie, Countess of Bismarck-Schönhausen, great-great-granddaughter of the “Iron Chancellor”, Otto von Bismarck. A portent of this economics minister’s future?

The Goerke House, Lüderitz

THE FAMILIAR PHRASE has a person in difficult circumstances being “between a rock and a hard place”. The Namibian town of Lüderitz is stuck between the dry sands of the desert and salt water of the South Atlantic — this is the only country whose drinking water is 100% recycled. Life in this almost-pleasant German colonial outpost on the most inhospitable coast in the world has always been something of a difficulty, but the allure of diamonds has at least made it profitable. One such adventurer who came from afar and made his fortune in this outer limit of the Teutonic domains was one Hans Goerke. (more…)

Some Words from Doorn on the Present Crisis

Loyal commenter Steve M. sends word that Kaiser Wilhelm II (currently of Doorn, the Netherlands) has written an open letter to His Excellency President Barack Obama of the United States.

Loyal commenter Steve M. sends word that Kaiser Wilhelm II (currently of Doorn, the Netherlands) has written an open letter to His Excellency President Barack Obama of the United States.

His Imperial Majesty objects to the current practice of appointing “czars” to deal with the various crises at hand, and offers a few alternative suggestions of his own.

Our readers will, no doubt, recall the Kaiser from his previous appearances on his blog here, here, and here.

Count von Stauffenberg: “We Live in a Society of Lemmings”

Count Franz Ludwig von Stauffenberg, the third son of Hitler’s would-be assassin Count Claus von Stauffenberg and brother to Gen. Berthold von Stauffenberg, recently spoke to the German magazine FOCUS about Germany’s ratification of the Lisbon Treaty. Stauffenberg, a father of four and grandfather of eight, has spent his life as an attorney and a politician for the Bavarian Christian Social Union party, serving in the Bundestag from 1976 to 1987 and as a Member of the European Parliament from 1984 to 1992.

FOCUS asked the Count about his participation in the German court challenge against the Lisbon Treaty.

“I see the way to [the Constitutional Court] as a last resort,” the Count said, “and had hoped that we could compel a re-think through an ordinary democratic manner, through argument, debate, and public pressure. This has totally failed. I’m not anti-European; I was long enough a CSU Member of the European Parliament. This Europe is no longer compatible with the basic structures of a democratic legal state.”

FOCUS: Has your case something to do with your experience as the son of the resistance fighter Count von Stauffenberg?

“No. My father expected that his children would … stand on their own as a man or woman. I didn’t go into politics from devout worship of my father, but because of the unsuccessful paths of my peers from the generation of 1968.”

FOCUS: Your action comes late. Why have you waited so long?

“In Brussels, there was no sudden seizure of power, but a systematic, persistent development, in which the Bundestag deputies, constantly obedient and even docile, incapacitated themselves. They see themselves as a reserve team for higher office rather than in their actual role as inspectors to reflect, as a counter force on equal footing.”

FOCUS: How can it be that so few see a risk in the Lisbon Treaty, and the rest should be so beaten with blindness?

“In Germany, almost no one wanted to hear concerns. We live in a society of lemmings.”

Link: Graf Stauffenberg: “Wir leben in einer Gesellschaft von Lemmingen” (In German)

Debating Stauffenberg

The recent release of the Hollywood film “Valkyrie” has brought the July ’44 plot back into the limelight. Much debate has focussed on the central figure of Count von Stauffenberg, especially the motivation and inspiration for his attempt to overthrow the Nazi regime. Writing in Süddeutsche Zeitung, Richard Evans (Regius Professor of Modern History at Cambridge) asks “Why did Stauffenberg plant the bomb?” Prof. Evans argues that the Count’s contempt for liberalism combined with his (Stefan George-influenced) romantic nostalgia « make him ill-fitted to serve as a model for the conduct and ideas of future generations » .

A week later, the Süddeutsche Zeitung published “Unmasking the July 20 plot“, a response to Evans by Karl Heinz Bohrer, the publisher of Merkur and a visiting professor at Stanford. Bohrer counters Evans on two fronts. « Firstly Evans’s lesson consisted of historical half truths, contradictory theses and slanderous allusions to Stauffenberg’s character; and secondly, such distortions differ very little from the view held by West German intelligentsia regarding the events of July 20th 1944 and the conspirators who were, for the most part, of aristocratic Prussian stock. … For a proper understanding of the how the plot against Hitler of 1944 is seen and judged today, one should bear in mind that today’s horizon has shifted. »

« There is no question that like Ernst Jünger and Gottfried Benn, Stauffenberg’s first spiritual influence, Stefan George, entertained pre-fascist fantasies. And there is also no question that the young Stauffenberg’s reverence for the medieval ‘reich’ was reactionary – in a similar vein to Novalis’s ideas in ‘Die Christenheit oder Europa’. But what does that mean? Neither of them had political ideas that could in any way have served as a model for democratic European societies in the second half of the twentieth century. But to fundamentalise this tautological insight to effectively deny the conspirators any moral or cultural relevance is blinkered and constitutes intellectual bigotry. George, Jünger and Benn’s pre-fascist fantasies contained important modernist symbols which mean they cannot be judged by political moralist criteria, alone. The same goes for Stauffenberg and his friends who – in a different way to the “idealistic” Scholl siblings and their circle – represented a calibre of ethics, character and culture class of which today’s politicians and other bureaucratic elites can only dream. »

In that same week, Bernard-Henri Lévy — the omnipresent French man of letters — waddled into the debate with “Beyond the war hero” in the pages of Le Point. BHL proclaims the release of “Valkyrie” is unquestionably good, for it is inherently good for the world to honour its heroes. « Riveting as it is however, this film poses certain questions that are too complex and too delicate to be resolved solely within the logic of the Hollywood film industry. »

In a moment of pure irony, Lévy attacks the lack of accuracy in the film while making a gross historical error himself. The philosopher asks whether « raising someone to hero status does not always happen, alas, to the detriment of precision, nuance and history itself. The film shows Stauffenberg’s integrity very well. It shows his courage, the nobility of his views, his firmness of spirit. But what does it tell us of his thoughts? What does it teach us about why he enthusiastically joined the Nazi Party in 1933? » In actual fact, while Stauffenberg’s family members were concerned that he was “turning brown” the Count never joined the Nazi Party; not in 1933, not ever.

In a sense, Lévy has answered his own question in that Stauffenberg’s elevation has apparently taken place to the detriment of precision and history in that Lévy is apparently unaware of quite central historical facts of the case.

Previously: Stauffenberg

Berlin to build ersatz Stadtschloß

Afraid of celebrating glorious past, a horrible future is created instead

Fresh from the glories of Dresden’s rebuilt Lutheran Frauenkirche, the city fathers of Berlin have decided to reconstruct the old Stadtschloß (“City Palace”) at the heart of the German capital, only not quite. Largely ignored by the anti-monarchist Nazis, the original Stadtschloß was damaged by Allied bombing and by shelling during the Battle of Berlin before the Communist government of East Germany demolished it entirely and built the horrendously ugly Palast der Republik (housing the Soviet satellite’s faux parliament) on the site. The Communist monstrosity has finally been demolished, but the authorities decided that, rather than restore the beautiful royal palace that once stood on the site, they will instead merely replicate three of the old structure’s façades, leaving one of the façades and most of the interior in a modern style.

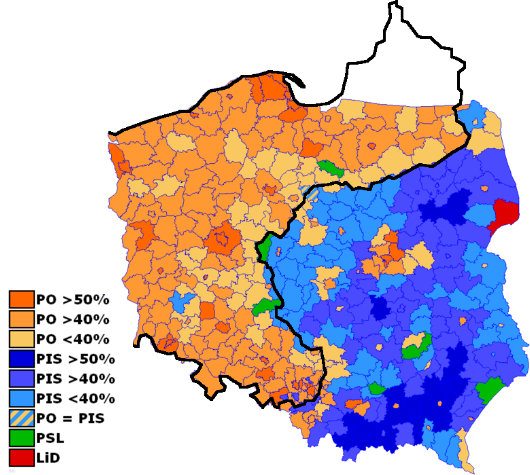

‘German’ Poland vs. ‘Russian’ Poland

A curiosity of the 2007 Polish parliamentary election

THIS MAP displaying the results of the 2007 general election for the Polish parliament is overlaid with an outline of the nineteenth-century border between the German and Russian empires.

The areas formerly ruled by the German Kaiser tend to back the right-wing liberal Platforma Obywatelska (“Civic Platform”) party, while those formerly ruled by the Tsar tend to support the conservative Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (“Law and Justice”) party.

The green represents the centrist-agrarian Polish People’s Party, while the dark red represents the already-defunct “Left and Democrats” coalition.

Source: Strange Maps

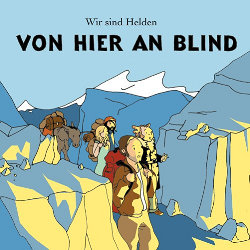

Von hier an blind

The German band “Wir sind Helden” is a quartet purveying inoffensive pop rock, and recommended to us by one of our continental cronies. For their 2005 album cover, Von hier an blind, the band commissioned a group portrait in the ligne-claire style. The design is an obvious homage to Hergé’s Tintin. “Wir sind Helden” are little-known in the English-speaking world, though they have played three sold-out concerts in London, and are available from the iTunes Music Store.

The German band “Wir sind Helden” is a quartet purveying inoffensive pop rock, and recommended to us by one of our continental cronies. For their 2005 album cover, Von hier an blind, the band commissioned a group portrait in the ligne-claire style. The design is an obvious homage to Hergé’s Tintin. “Wir sind Helden” are little-known in the English-speaking world, though they have played three sold-out concerts in London, and are available from the iTunes Music Store.The Pester Lloyd

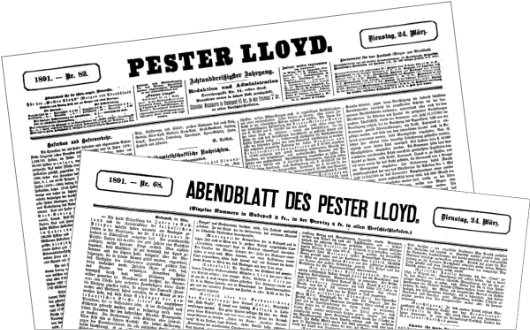

The Hungarian capital’s German-language newspaper has been “independent, pluralistic, steeped in tradition” since 1854

The fall of the Iron Curtain nearly twenty years ago after a half-century of Communist domination in Eastern Europe afforded an opportunity to revive many of the traditions and institutions which — while they had survived monarchy, republicanism, and fascism — were annihilated by the all-consuming Red totalitarianism. One such institution that has risen from the ashes is Hungary’s once-revered German-language newspaper, the Pester Lloyd.

First appearing in 1854, when Buda and Pest were still two cities flanking the banks of the Danube, the Pester Lloyd was the leading German journal in Hungary. Printed daily with morning and evening editions, the “Pester” in the paper’s name refers to Pest, while “Lloyd” is in imitation of Lloyd’s List (the London shipping & commercial newspaper founded in 1692 by the eponymous properitor of Lloyd’s Coffee Shop and still going strong today). The paper first gained prominence under the editorial leadership of Dr. Miksa (Max) Falk, who had famously tutored the Empress Elisabeth in Hungarian and instilled in the consort a particular love for the Hungarian kingdom.

First appearing in 1854, when Buda and Pest were still two cities flanking the banks of the Danube, the Pester Lloyd was the leading German journal in Hungary. Printed daily with morning and evening editions, the “Pester” in the paper’s name refers to Pest, while “Lloyd” is in imitation of Lloyd’s List (the London shipping & commercial newspaper founded in 1692 by the eponymous properitor of Lloyd’s Coffee Shop and still going strong today). The paper first gained prominence under the editorial leadership of Dr. Miksa (Max) Falk, who had famously tutored the Empress Elisabeth in Hungarian and instilled in the consort a particular love for the Hungarian kingdom.

Sorb Serf Story Shown on Silver Screen

Otfried Preußler’s retelling of old Wendish legend hits German cinemas

Follow your dreams! It may sound like a Hollywood cliché, but what’s a fourteen-year-old orphaned Sorb peasant to do? Currently showing in German cinemas, “Krabat” is the first film version of Otfried Preußler’s 1971 novel of an old Sorbian tale whose eponymous protagonist is a beggar boy in the eastern Saxony of the early 1700s. Krabat is plagued by dreams of an old watermill outside the tiny hamlet of Schwarzkollm, which seems to be operational though farmers never bring grain to be milled.

NRC, among others, gets it right

The Netherlands’ premier broadsheet has gone partly English online

The moderate liberal Dutch broadsheet NRC Handelsblad is the latest of a series of European periodicals looking for a more international readership by translating part of their content into English for distribution on the world wide web. “NRC International” is partnered with the German weekly magazine Der Spiegel, itself a pioneer in featuring English content in an “international” section of its website. Aside from NRC and Der Spiegel, other news outlets now featuring web-only English-language content are Germany’s Die Welt and Hungary’s Heti Világgazdaság, while Eurozine features translated and original content from a broad spectrum of continental reviews and journals. Sadly, Sign and Sight recently had to reduce their “From the Feuilletons” — looking at the culture pages of German-language newspapers — from a daily to a weekly feature. Sign and Sight also features a weekly “Magazine Roundup” doing the rounds of a wide variety of European, Asian, and American magazines.

The move comes as print newspapers of the conventional variety across Europe and America are losing circulation. Some Manhattan newsstands have seen takers for the Sunday New York Times fall by as much as 80% in the past few years. The New York Times and Wall Street Journal both recently narrowed their page width in a move to save paper costs; the change, however, also means less room for advertising and a more ungainly appearance.

South Africa’s Herald, meanwhile, has bucked the gloomy trend and increased its readership by 14.5% in the past year. The Herald, the Eastern and Southern Cape’s regional broadsheet, attributes its success to a visual redesign and reorienting content to encourage readers to link up with the newspaper’s website. South Africa is also home to The Times (not to be confused with the older Cape Times), a new upmarket broadsheet newspaper launched as a daily extension of the century-old Sunday Times. The weekday Times was started a year ago and its circulation since just June has seen a 10.4% increase.

A major problem for the industry is that formerly high-end newspapers have driven down the quality of their product to a suicidal extent over the past decades. The middle market, for better or worse, is dead, and publishers have three alternatives to this disappearing sector: 1) go lowest-common-denominator — as The Times of London has done, with only moderate success; 2) go up-market — The Times and Sunday Times of South Africa have proved worthwile; or 3) go niche — the New York Observer is still in business after two decades of aiming towards Manhattan’s yuppie community.

Whichever path taken, integrating print and web operations is vital for the survival of print newspapers and other “dead tree” media. That European newspapers are providing at least part of their content in English is helpful in keeping up with events and ideas in countries like Germany, the Netherlands, and Hungary as our native English-language media are tightening their belts and cutting foreign correspondents and coverage. I hope more non-English papers follow this trend and help to permanentize it.

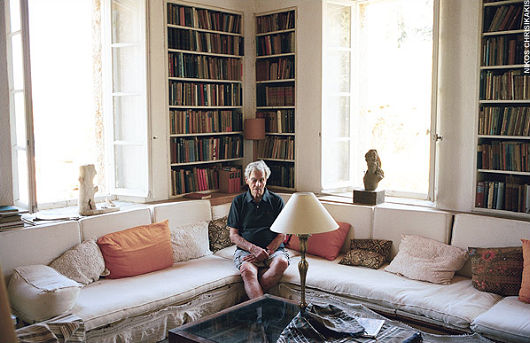

‘The man who walked’

The Daily Telegraph — 6 September 2008

At 18 he left home to walk the length of Europe; at 25, as an SOE agent, he kidnapped the German commander of Crete; now at 93, Patrick Leigh Fermor, arguably the greatest living travel writer, is publishing the nearest he may come to an autobiography – and finally learning to type. William Dalrymple meets him at home in Greece

‘You’ve got to bellow a bit,’ Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor said, inclining his face in my direction, and cupping his ear. ‘He’s become an economist? Well, thank God for that. I thought you said he’d become a Communist.’

He took a swig of retsina and returned to his lemon chicken.

‘I’m deaf,’ he continued. ‘That’s the awful truth. That’s why I’m leaning towards you in this rather eerie fashion. I do have a hearing aid, but when I go swimming I always forget about it until I’m two strokes out, and then it starts singing at me. I get out and suck it, and with luck all is well. But both of them have gone now, and that’s one reason why I am off to London next week. Glasses, too. Running out of those very quickly. Occasionally, the one that is lost is found, but their numbers slowly diminish…’

He trailed off. ‘The amount that can go wrong at this age – you’ve no idea. This year I’ve acquired something called tunnel vision. Very odd, and sometimes quite interesting. When I look at someone I can see four eyes, one of them huge and stuck to the side of the mouth. Everyone starts looking a bit like a Picasso painting.’

He paused and considered for a moment, as if confronted by the condition for the first time. ‘And, to be honest, my memory is not in very good shape either. Anything like a date or a proper name just takes wing, and quite often never comes back. Winston Churchill – couldn’t remember his name last week.

‘Even swimming is a bit of a trial now,’ he continued, ‘thanks to this bloody clock thing they’ve put in me – what d’they call it? A pacemaker. It doesn’t mind the swimming. But it doesn’t like the steps on the way down. Terrific nuisance.’

We were sitting eating supper in the moonlight in the arcaded L-shaped cloister that forms the core of Leigh Fermor’s beautiful house in Mani in southern Greece. Since the death of his beloved wife Joan in 2003, Leigh Fermor, known to everyone as Leigh Fermor, has lived here alone in his own Elysium with only an ever-growing clowder of darting, mewing, paw-licking cats for company. He is cooked for and looked after by his housekeeper, Elpida, the daughter of the inn-keeper who was his original landlord when he came to Mani for the first time in 1962.

It is the most perfect writer’s house imaginable, designed and partially built by Leigh Fermor himself in an old olive grove overlooking a secluded Mediterranean bay. It is easy to see why, despite growing visibly frailer, he would never want to leave. Buttressed by the old retaining walls of the olive terraces, the whitewashed rooms are cool and airy and lined with books; old copies of the Times Literary Supplement and the New York Review of Books lie scattered around on tables between Attic vases, Indian sculptures and bottles of local ouzo.

A study filled with reference books and old photographs lies across a shady courtyard. There are cicadas grinding in the cypresses, and a wonderful view of the peaks of the Taygetus falling down to the blue waters of the Aegean, which are so clear it is said that in some places you can still see the wrecks of Ottoman galleys lying on the seabed far below.

There is a warm smell of wild rosemary and cypress resin in the air; and from below comes the crash of the sea on the pebbles of the foreshore. Yet there is something unmistakably melancholy in the air: a great traveller even partially immobilised is as sad a sight as an artist with failing vision or a composer grown hard of hearing.

I had driven down from Athens that morning, through slopes of olives charred and blackened by last year’s forest fires. I arrived at Kardamyli late in the evening. Although the area is now almost metropolitan in feel compared to what it was when Leigh Fermor moved here in the 1960s (at that time he had to move the honey-coloured Taygetus stone for his house to its site by mule as there was no road) it still feels wonderfully remote and almost untouched by the modern world.

When Leigh Fermor first arrived in Mani in 1962 he was known principally as a dashing commando. At the age of 25, as a young agent of Special Operations Executive (SOE), he had kidnapped the German commander in Crete, General Kreipe, and returned home to a Distinguished Service Order and movie version of his exploits, Ill Met by Moonlight (1957) with Dirk Bogarde playing him as a handsome black-shirted guerrilla.

It was in this house that Leigh Fermor made the startling transformation – unique in his generation – from war hero to literary genius. To meet, Leigh Fermor may still have the speech patterns and formal manners of a British officer of a previous generation; but on the page he is a soaring prose virtuoso with hardly a single living equal.

It was here in the isolation and beauty of Kardamyli that Leigh Fermor developed his sublime prose style, and here that he wrote most of the books that have made him widely regarded as the world’s greatest travel writer, as well as arguably our finest living prose-poet. While his densely literary and cadent prose style is beyond imitation, his books have become sacred texts for several generations of British writers of non-fiction, including Bruce Chatwin, Colin Thubron, Philip Marsden, Nicholas Crane and Rory Stewart, all of whom have been inspired by the persona he created of the bookish wanderer: the footloose scholar in the wilds, scrambling through remote mountains, a knapsack full of books on his shoulder.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Waarburg October 2, 2024

- A Prize for the General September 23, 2024

- Articles of Note: 17 September 2024 September 17, 2024

- Equality September 16, 2024

- Rough Notes of Kinderhook September 13, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories