Finance

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Cross-Border Raids into Finance

The St James’s offices of Aim-quoted Cluff Gold in London resemble an explorer’s den: an antique globe, exotic objets d’art on the walls and a bust of Jan Smuts, the South African statesman, greeting visitors in the corridor.

It is the work of Algy Cluff, the buccaneering 71-year-old chairman of the west African gold producer. Just returned from shooting guinea-fowl in the Kalahari Desert, Mr Cluff’s air of patrician derring-do could have been sketched by the pen of Evelyn Waugh.

Having worked in Africa long before it became a fashionable investment destination Mr Cluff is modest about the key to success in frontier markets: “Good manners.”

It used to be the certifiable Cusack position that the realms of finance & business were dead dull and to be avoided at all costs. I do read the Financial Times fairly often — especially for its praise-worthy and restrained weekend edition — but I’ve always steered well clear of the Companies & Markets section that appears in the paper’s Monday-through-Friday editions. A week or so ago, inspired by some bizarre exotic curiousity, I wandered over the borders into the territory of Companies & Markets for the first time, and was fascinated by the intricacy of what I found, as well as how interesting it all was.

Also, when younger I thought only boring people went into finance, but after graduating from university and seeing everyone toddle along their various paths, I find that about half the fun and interesting people I know have ended up doing somethingerother financial — another assault on Cusack’s anti-finance defences. I am aided in my exploration of this intricate world by a nifty little book I’ve stolen from a friend’s collection: How to Read the Financial Pages by Michael Brett; basically finance for layfolk such as yours truly. And of course I am still enjoying Philip O’Sullivan’s Market Musings.

Admittedly, much of this is sparked by the initial public offering of Glencore. There’s something splendidly boyish and fun about commodities (especially gold, as the above-mentioned Mr Cluff surely knows) and Glencore’s massive corner of the global commodities market is truly beyond the dreams of avarice. There is, apparently, gold in them thar hills.

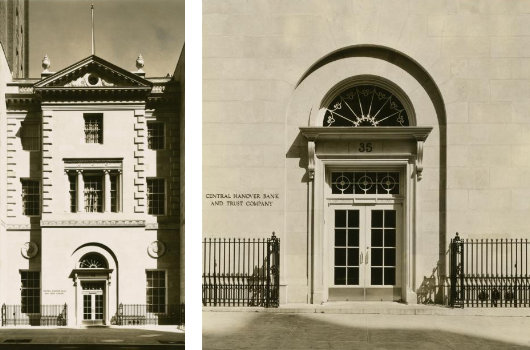

The Hanover Bank: A Classical Gem

No. 35, East Seventy-second Street

Passing by, as I sometimes do, the Chase branch bank at East 72nd St., I think to myself “There’s a fine establishment, in which I should keep my money”. The thought never jumps from theory to practice, however, as I am a patriot in everything but finance, and keep my florins safe with the Hongkong & Shanghai Bank instead. Nonetheless, it’s a handsome building, and the Central Hanover Bank & Trust Company should be commended for erecting it. Central Hanover merged with the Manufacturers Trust Company in 1961 to form Manufacturers Hanover (“Manny Hanny”), which was taken over by Chemical Bank in 1991, which was acquired by Chase Manhattan Bank in 1995, which merged with J.P. Morgan in 2000, and the consumer & commercial banking arm of J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. is now simply known as “Chase”.

While the original Chase National Bank was only formed in 1877, with all these mergers and acquisitions, “Chase” can now trace its lineage back to the foundation of the Bank of the Manhattan Company in 1799, the second oldest bank after the Bank of New York. But — would you believe it? — “Chase” is now headquartered not in the hallowed caverns of Wall Street but — wait for it — Chicago, Illinois!

Questions on the Present ‘Crisis’

I know next to nothing about finance and economics, but since stock prices which had previously been ridiculously inflated are now falling to their actual value: isn’t that a good thing? Shouldn’t we be glad the correction is finally happening and shouldn’t we have wished it had come sooner? Isn’t this something that should provoke a sigh of relief? Doesn’t all this panic on Wall Street make the financiers look like a bunch of little girls?

Of course in the old days, you had men in charge. J.P. Morgan was the head of J.P. Morgan, and by gum that meant something. There was someone to be accountable to. Nowadays, no one person owns anything, which is to say, everything is owned by everyone. As the American Loyalist of old oft said: “I would rather be ruled by one tyrant a thousand miles away then by a thousand tyrants not one mile away.” When you had a giant like Morgan around, he could invite everyone round and sort things out. Now, CEOs come and go and are accountable, not to one man, but to “shareholders”, who are apparently legion, and not terribly keen on holding their henchmen to account during the times when the profits are flowing in. The same goes for finance ministers and the central bankers.

Out with them all, I say, and bring back Mr. Morgan!

Mr. Morgan did not appreciate having his photograph taken.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories