Conservatism

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

Caro had been a Nieman Fellow at Harvard studying urban planning and land use when he came up with the idea for the book. He thought it would take him nine months, but extensive research and over five-hundred in-person interviews meant it took eight years to complete.

Caro then started working on his study of Lyndon Baines Johnson, the first volume of which emerged in 1982 and the fifth (and final?) one he is still working on. (At the end of the fourth, LBJ had just become president.)

But where does he write? Christopher Bonanos of New York magazine finds out:

It’s an ageless space, one where it could be last week or 1950 inside, matter-of-fact and utilitarian. A couple of bookcases, a plywood work surface, corkboard with outlines tacked up, an old brass lamp, an underworked laptop for emails, a Smith-Corona typewriter. The desk chair is hard wood with no cushion. There’s a saltshaker next to the pencil cup for when Ina brings a sandwich out at midday. The desk has a big half-moon cutout, same as the one back in New York, so he can rest his weight on his forearms and ease his bad back. That arrangement was recommended by Janet Travell, the doctor who grew famous for prescribing John F. Kennedy his Boston rocker. She, with Ina, is a dedicatee of The Power Broker.

He bought the prefab shack, he says, from a place in Riverhead for $2,300, after a contractor quoted him a comically overstuffed Hamptons price to build one. “Thirty years, and it’s never leaked,” he says. This particular shed was a floor sample, bought because he wanted it delivered right away. The business’s owner demurred. “So I said the following thing, which is always the magic words with people who work: ‘I can’t lose the days.’ She gets up, sort of pads back around the corner, and I hear her calling someone … and she comes back and she says, ‘You can have it tomorrow.’”

Does he write out here every day? “Pretty much every day.” Weekends too? “Yeah.” Does he go out much while he’s on the East End? “We have two friends who live south of the highway, and I said to Ina, aside from them, I’m not going this year.” There are other writer friends nearby in Sag Harbor, and they get together, but at this age, Caro admits a little sadly, they’re thinning out. He’ll be 89 this fall.

■ George Grant is a still-underappreciated giant of political thinking in the English-speaking world. He is too little known outside his native Canada, which he sought to defend from the undue overwhelming influence of its sparkling and glamourous southern neighbour. Next year marks the sixtieth anniversary of his Lament for a Nation.

Of all people, a research fellow at Communist China’s Institute for the Marxist Study of Religion — George Dunn — has written a thoughtful introductory overview of Grant’s life and thinking: George Grant and Conservative Social Democracy in Compact.

■ Katja Hoyer mused on an overlapping theme in a recent Berliner Zeitung column which she has helpfully presented in English as well:

A diplomat close to the SPD recently told me that he couldn’t understand why working-class people in particular voted for the AfD. Things weren’t so bad for them, after all. I didn’t bother pointing out that rampant inflation, high energy prices and rising rents have had a hugely detrimental effect on the living standards of people with low and middle incomes because his analysis completely misses the point.

Germany’s working-class voters, Katja argues, feel forgotten by the parties founded to represent them.

■ Since the fall of the Berlin Wall — and earlier in Angledom — political conservatism has effectively been taken over by economic liberalism.

This has denied the centre-right from learning from and deploying useful experience from outside liberalism, with the wisdom of figures as varied as Benjamin Disraeli, Giorgio La Pira, Charles de Gaulle, and Thomas Playford essentially ignored or sidelined.

Kit Kowol’s new book Blue Jerusalem: British Conservatism, Winston Churchill, and the Second World War explores the visionary side of wartime Conservatism. Dr Francis Young offers his take on Tory utopias in The Critic.

■ From a similar era, Andrew Ehrhardt writes at Engelsberg Ideas on Ernest Bevin and the moral-spiritual dimension of British foreign policy.

■ Our friend Samuel Rubinstein has studied at Oxford, Leiden, and the Sorbonne — technically the oldest universities in their three respective countries (although we all know that Leuven is in fact the doyen of Netherlandish academies).

Sam offers an incredibly interesting comparison of the experiences of these three institutions in a humble essay on his Odyssean education:

I arrived in Leiden, armed with my phrase-book, with some ambitions of learning Dutch. The first blow came at the Starbucks in the train station, when the barista answered my Ik wil graag in English without hesitating. The second came the following day when I tried again, at a different café – only this time it seemed that the barista (Spanish? Italian?) didn’t know much Dutch either: even the natives were placing their orders in English. So I gave up – save one hobby, reading Huizinga in the original. I got myself an attractive coffee-table edition of Herfsttij and managed a page or so a day, strenuously piecing it together from my English, German, and smattering of Old English. I still haven’t the faintest idea how to pronounce any of it.

■ And finally, those of us who love Transylvania will enjoy Toby Guise’s summary of the Fifth Transylvanian Book Festival in The New Criterion.

Articles of Note: 20 May 2024

British right-liberals are sometimes accused of yearning for “Singapore-on-Thames” but they would, for example, recoil from the state-backed housebuilding that Singapore relies on.

The indomitable Lola Salem visited the flourishing Straits state.

“In everyday life,” she writes, “the state endeavours to demonstrate its relevance and ensure citizens feel that they have a stake in what is achieved in their name.”

But the foundation of Singapore’s undeniable strengths is “a complex tapestry of trade-offs that Western leaders wilfully or inadvertently ignore.”

■ Romania is a delight to visit, but I have only been to Transylvania which is somehow another category entirely. A bit like if you’ve been to Britain, but only (“only”) Scotland.

Christopher Brunet says that Romanians themselves tell foreigners to visit Transylvania and avoid their own capital city. He decided to do the opposite and spent a month as a boulevardier in Bucharest.

Brunet reports back that Romania is quietly doing great.

■ Without meaning to damn with faint praise, David Warren is one of the great Canadians of our age. I long felt an almost spiritual connection to him but, though we have never met in person, I assuaged myself that we were at least infrequent correspondents.

One day I went to check when was the last email I had from him only to be surprised to find that I had never, in fact, corresponded with him at all. So I wrote to him and told him this, which provoked a reply saying that he too had assumed we had written to one another several times. Two mastodons bellowing across primieval swamps, or the Atlantic ocean, or the Canadian border when I was still in New York.

Amongst David’s many accomplishments was the foundation and editorship of The Idler (1985-1993), the greatest Canadian magazine ever printed. Canada generously shovels endless cash at its literary efforts in the hope of producing something homegrown that can survive the onslaught of popular culture from its peaceful neighbours to the south.

Despite critical acclaim and obvious excellence, The Idler’s unfashionable conservatism meant that it never had access to the largesse distributed by the Canada Council for the Arts. As that body funded 96 different publications, David branded The Idler as “Canada’s 97th best literary magazine”.

David writes about his experience editing the review that described its ideal reader as “a sprightly, octogenarian spinster with a drinking problem, and an ability to conceal it”.

19¾ in. x 26 in.; (link)

■ Edinburgh was the site of the second-most venerable legislature in the English-speaking world, and it is worth wending a wander into Old Parliament Hall — one of the city’s three parliament buildings.

We’re all familiar with the way the House of Commons sits, having inherited the antiphonal seating of the old Chapel Royal of St Stephen in the Palace of Westminster.

At Old Edinburgh Reborn, Dr Robert Sproul-Cran has penned a very thorough examination of how seating was arranged in the Estaits of the Realm, the Scots parliament of old.

■ It would take a heart of stone not to be amused by the life and times of King Zog of Albania. He may have been a vulgar gangster but he had a certain flair, and one appreciates the imaginative even when it is self-aggrandising.

Daniel Marc Janes reviews a new book about the Illyrian potentate.

(And if you haven’t read the Albanian writer Ismail Kadare, you should.)

■ The sheer freakishness of American campus life is as fascinating as it is alarming.

The universities of the United States are some of the most influential factors of social control in the world, and whatever weird innovations you experience in your professional or public life worldwide today are usually explained by something that was going on at Yale or Stanford five or ten years before.

Ginevra Davis has written a sad chronicle of Stanford University’s war against social life. They even let an artificial lake go dry to stop people enjoying it!

■ What is more satisfying than the brilliant self-taught amateur who outshines the experts?

John Steele Gordon writes about the great astronomer E.E. Barnard.

■ A new documentary film about South Korea’s founding father, Rob York reports, has led to a newfound appreciation of the much-maligned Syngman Rhee.

■ I am a fan of the neglected postwar American conservative thinker Peter Viereck, and of course everyone is a fan of Metternich. (Viereck was previously mentioned here in January thanks to Samuel Rubinstein.)

Hamilton Craig covers both figures in his suggestion of how Yoram Hazony’s “NatCon” conferences can learn from Austria’s greatest chancellor.

■ I recently wrote about Telephone Kiosk No. 2, but Clive Aslet does it better.

■ Mary Harrington claims that conservatism is dead and the future belongs to right-wing progressives like Bukele.

■ Whoever Pimlico Journal is says we need to stop valorising dead centrist Tories.

■ And it turns out that the role of Patriarch of Constantinople is actually an arms-length Langley job. (Caveat emptor.)

30⅓ in. x 22½ in.; (link)

Articles of Note: 29 January 2024

A lively Doubleyoo-Ess once took me to lunch at the New Club and, in whispered tones, pointed out a gentleman sitting at another table.

“He is the world’s leading expert on the Scots tongue,” my friend explained.

“But he was excommunicated by all the other experts on Scots when he pointed out that eighty per cent of Scots words are interchangeable with Northumbrian English.”

Scots is fascinating for its closeness to English and its distinction. Those who’ve had the pleasure of tarrying awhile in the Netherlandic world (whether in Europe, the Cape of Good Hope, or elsewhere) can detect the odd affinities to Dutch and Afrikaans — reminding you that the North Sea was once a highway, not a barrier.

Luka Ivan Jukic has written an enlightening exploration of how and why Scotland lost its tongue.

Jukic contends there are no signs of revival, which I dispute. There is a much increased interest in the use of Scots, but it feels contrived and falls somewhat flat. If you take a look at the Scots column in The National newspaper, it comes across as the ravings of a kook something akin to Anglish.

■ Amongst the many of Scotland’s joys is the pleasure of just looking at its buildings.

Witold Rybczynski pleads “Give us something to look at!” in his account of why ornament matters in architecture.

■ The New York Post — founded by Alexander Hamilton in 1801 and thus the Empire State’s oldest and most venerable newspaper — reports that the world’s oldest and most venerable forest has been discovered right in the heart of the Catskill Mountains.

This is one of the most beautiful places in America, especially when the leaves begin to turn in autumn, and features widely in the old stories transcribed by Washington Irving and others.

The name of the Catskills is believed to be from the catamounts that used to roam the woods and bergs when our Dutch forefathers of old first arrived in the valley of the Hudson. Our earliest record of it is on a map by Nicolaes Visscher père from 1656 — and pleasingly the local magazine retains the old spelling in its name of Kaatskill Life.

This fossilised forest within the Catskills is believed to date from 385 million years ago (for those who doubt the Ussher chronology — and we remain open-minded ourselves) and was discovered at the bottom of an old quarry.

■ As a precocious teenager I remember a visit to the maritime museum in Rochefort on France’s Atlantic coast that included a fascinating display of the intricacies and accomplishments of global shipping, housed in the long old ropeworks that kept France’s navy afloat in the era of sail.

It’s all been kicking off in the Red Sea, which inspired Wessie du Toit to write that the shipping container is an uncanny symbol of modern life

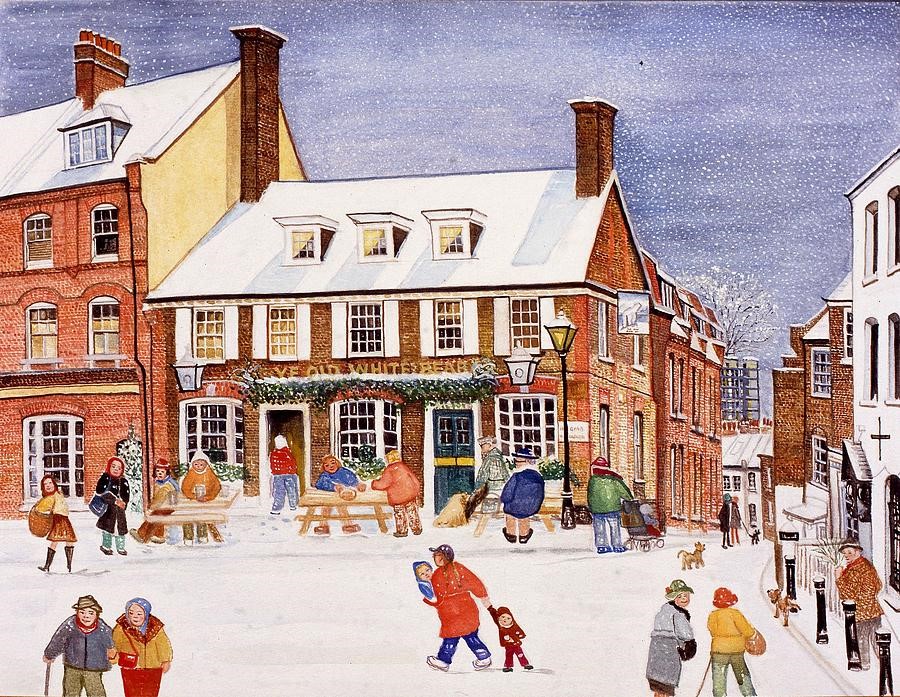

■ Some people claim there is no life outside of NW3, but as much a fan of Hampstead as I am, my first loyalty in London neighbourhoods is firmly lodged in Southwark. (Pimlico is high on the list, too.)

Many will pine for those precious late summer afternoons idly dawdling on the Heath, but Hampstead in winter has its distinct pleasures. For me, it’s curdling up with a pile of books beside the coal fire in the Old White Bear.

In the Christmas issue of The Oldie, Peter York wrote about the rise and fall of arty Hampstead.

■ One of our Hampstead mates is originally a West Country man and now finds himself even further west, studying law in California.

For a New Yorker, California is The Great Other. If not quite a rival, then certainly something we are always being compared against.

Naturally, one looks down on California, but also with a certain envy. If ever America had a golden moment when imperial might was combined with the simple goodness of life, it must have been coastal California from the 1930s to 1960s — with a hint of survival into the 1980s.

California’s decline is evident to all, though its power and influence is still vast (as the iPhone in your pocket proves). The Manhattan Institute recently devoted an entire issue to the question of Can California Be Golden Again?

I haven’t had a chance to read much of it, but I did enjoy Jordan McGillis’s article on how San Diego retains many of the qualities that once made California the envy of the world.

■ Peter Viereck ranks amongst the names of slightly neglected thinkers in the agora of American conservatism. Reading him always brings some insight, but I never knew much about the man himself.

Samuel Rubinstein supplies a fascinating account of the man and his thinking in Peter Viereck: Psychoanalyst of Nazism.

■ National treasure Peter Hitchens has spent his life hating the ogre Ted Heath, destroyer of worlds. I will never forgive him for what he did to England’s ancient counties and boroughs.

But Hitchens the Heath Hater, with his typically thoughtful approach, offers a reconsideration of the man.

■ All politics is local: Fred de Fossard writes about how EU-obsessed Lib Dems are ruining Bath rather than guarding one of the most precious jewels of English cities.

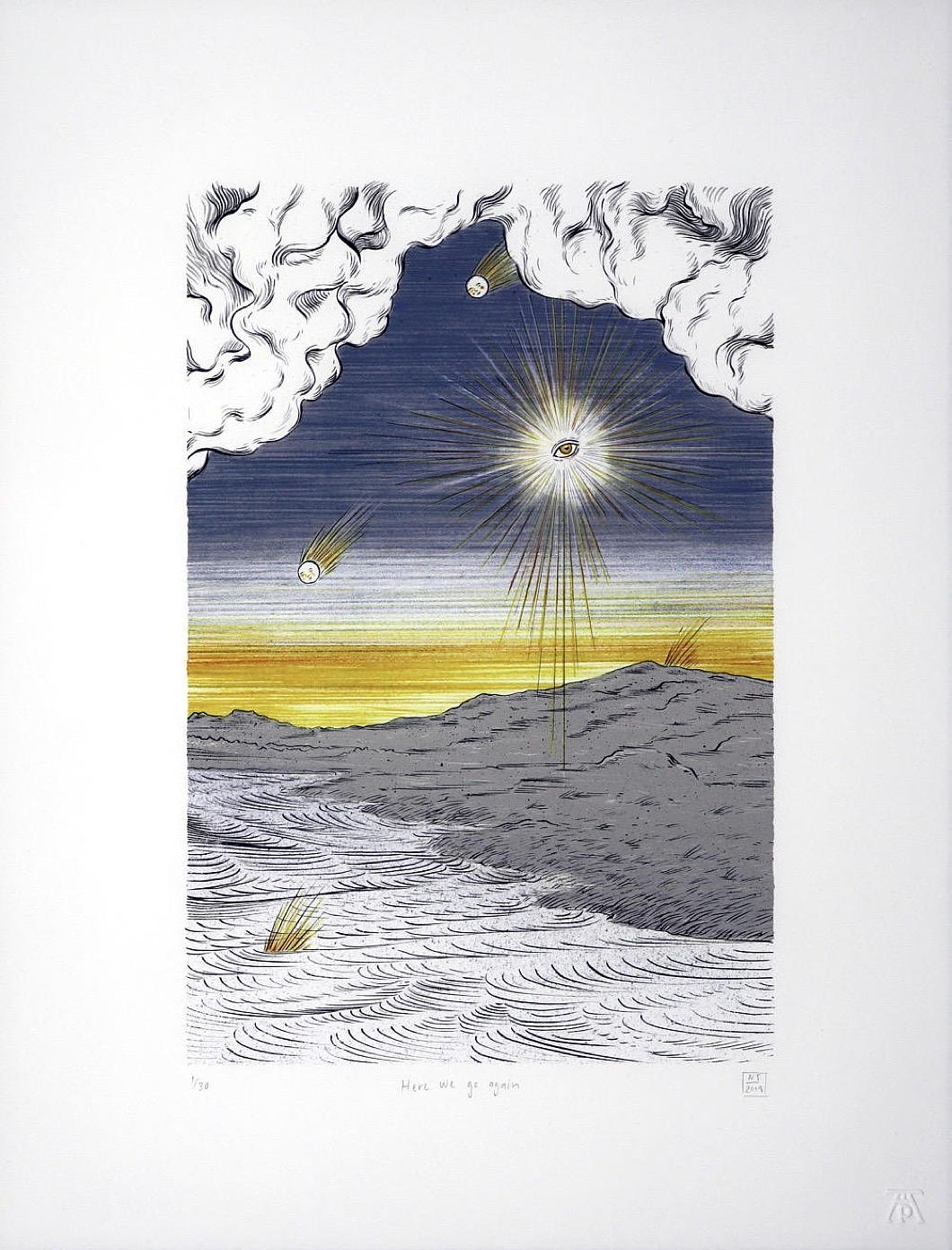

■ We leave you with this six-colour lithograph from the Pretoria-based artist Nina Torr entitled ‘Here we go again’ (an edition of thirty, available from the Artists’ Press):

Gaullist California

A friend well conversant in my ongoing crusade to remind today’s centre-droit of the utility of the Gaullist experience writes in:

The Golden State once practised a very successful form of Cal-Gaullism, developing world-class infrastructure, research universities, new industries… and much of the place was solidly conservative.

Once upon a time, parts of Southern California (including Orange County) were deemed the most conservative places in America, from which Nixon, Reagan, and others sprang.

San Francisco, though still beautiful, is certainly now well past its prime; I remember that white tie and tails were still seen there regularly as late as the ’80s.

The Polish church in Los Angeles was built to serve the large number of Polish exile families (with fathers who were aerospace engineers trained in the RAF like mine) who came from the UK and Canada to work in what was then the world centre of the aerospace and defence industry — “the Gunbelt in the Sunbelt”.

Articles of Note: 15.I.2021

• Autumn and winter are a time for ghouls and ghosts and eery tales. At Boodle’s for dinner two or three years ago I sat next to the wife of a friend and exchanged favourite writers. I gave her the ‘Transylvanian Tolstoy’ Miklos Banffy, in exchange for which she introduced me to the English writer M.R. James — whose work I’ve immensely enjoyed diving into. The inestimable Niall Gooch writes about Christmas, Ghosts, and M.R. James, as well as pointing to Aris Roussinos on how Britons’ love for ghostly tales is a sign of (little-c) conservatism.

• There can be few figures in English history more ridiculous than Sir Oswald Mosley. But the Conservative MP who became a Labour government minister and then British fascist führer-in-waiting was also forceful in his condemnation of the savagery unleashed by the Black-and-Tans. In 1952 a local newspaper in Ireland announced that Sir Oswald and Lady Mosley “charmed with Ireland, its people, the tempo of its life, and its scenery” had taken up residence at Clonfert Palace in Co. Galway. “Sir Oswald,” the paper noted with amazing restraint, “was the former leader of a political movement in England.” Maurice Walsh presents us with the history of Mosley in Ireland.

• The death of the late Lord Sacks, Britain’s former Chief Rabbi, was the subject of much lament. Rabbi Sacks was obviously no Catholic, but his intellect, frankness, and generosity were much appreciated by Christians. Sohrab Ahmari, one of the editors at New York’s most ancient and venerable daily newspaper, offers a Catholic tribute to Jonathan Sacks.

• “Education, Education, Education” has become a mantra in the past quarter-century and while there is a point there’s also a certain error of mistaking the means to an end for the end itself. After all, in the 1930s Germany was the most and highest educated country in the world. At Tablet, probably America’s best Jewish magazine, Ashley K. Fernandes explores why so many doctors became Nazis.

• Fifty years ago the great people of the state of New York rejected both the Republican incumbent and a Democratic challenger to elect the third-party Conservative candidate James Buckley as the Empire State’s senator in Washington. At National Review Jack Fowler tells the gleeful story of the unique circumstances that brought about this victory for Knickerbocker Toryism and how Mr Buckley went to the Senate.

Champagne and the World

Champagne can provoke a great deal of philosophy. I’ve often said that champagne and the Catholic faith are the only two universally applicable things in the universe – appropriate for births, deaths, good times and bad, early, late, or a mundane afternoon.

Iain Martin has a brief but excellent piece ‘On Wine’ discussing Churchill’s drinking habits, and wondering whether he really was permanently pissed during the war (unlike the teetotal vegetarian Mr Hitler).

Interesting in itself, but Mr Martin relates a trip to Épernay where he blind tastes a Margaux from 1873. By that time it should have tasted like vinegar but instead it was “beautifully balances and perfectly drinkable”.

Looked after carefully, not shaken about or disturbed unnecessarily, it evolved and endured. It retained its essential characteristics, giving pleasure to later generations. If only we nurtured political institutions and good government according to the same principle.

Nothing could better show the essence of a sound worldview.

Fillon: Which Right?

A Rémondian Analysis of the French Presidential Candidate

One of the most significant contributions of the historian and political scientist René Rémond was his theory regarding the tendencies of the French right wing. He contended that, broadly speaking, there are three right wings in France: legitimist, bonapartist, and orleanist. These terms are not bound by their historic use, but rather (Rémond argued) serve as useful guides to understanding French conservatism today.

Gaullism, for example, with both its populism and its reliance on the authority of a charismatic leader, is classified as bonapartist. Social conservatism, meanwhile, with its affinity for the Church and for tradition, comes in under legitimism. And economic liberalism — the bourgeois supremacy of the markets — is orleanist.

What to make of the current presidential candidate of the French right, M François Fillon? The Québécois website Dessinons les élections (“Let’s draw the elections”) sought to apply a Rémondian analysis of Monsieur Fillon in one of its weekly cartoons (by Frédéric Mérand & Anne-Laure Mahé).

Their conclusions are as follows:

Legitimism: 60%

– social conservatism

– Christian values

– order and traditionOrleanism: 30%

– economic liberalismBonapartism: 20%

– a sense of the State

– idea of the providential man with reference to de Gaulle

Of course, many now think that, due to the usual scandals, Fillon is yesterday’s man and that Macron is the man of the hour. The two are chalk and cheese. Fillon is the family man from the country, loves hunting, and clings to the values of the Church. Macron is a socialist énarque and investment banker who married one of his school teachers (twenty-four years his senior).

The elephant in the room: Madame Le Pen. The leader of the Front national will, there is almost no doubt, top the first round of the election but then, in the second round, will have to face whichever other candidate gains the next highest number of votes. Whoever that candidate is will almost certainly gain all the anti-frontiste votes and be propelled to victory and the Elysée.

At the moment, it looks like the second candidate will only have to win around 22 per cent of the vote in order to effectively gain the presidency. Such a low level of actual support is one of the things the 1962 changes to the constitution sought to prevent, but when faced with an FN candidate as in 2002 or (presumably) this year the two-round system fails to prevent this.

As usual, the conservatives are calling for change and the progressives arguing for stasis, but it remains to be seen which option France will choose.

Voltaire’s Works Are Not Dead

They Are Alive: And They Are Killing Us

“It was a little after nine in the evening; the sun was setting, the weather superb. … Nothing is rare, nothing is more enchanting than a beautiful summer evening in St Petersburg. Whether the length of the winter and the rarity of these nights, which gives them a particular charm, renders them more desirable, or whether they really are so, as I believe, they are softer and calmer than evenings in more pleasant climates.”

The Soirées Saint-Petersbourg of Joseph de Maistre are philosophical dialogues that sometimes border on the mystical and delve into the dark recesses of human nature. They are eloquent, fascinating, and beautiful, traversing a broad range of subjects while hovering around evil and why it exists in the world.

In this extract from the Fourth Dialogue, the Count — generally taken to represent the author’s own view — objects to the young Chevalier citing Voltaire approvingly.

A critic might call it a rant; if so, it is at least a beautiful one:

Tuesday 9 February 2016

For 175 years, the United States was a consciously anti-conservative country. But after the Second World War, that changed entirely. Daniel McCarthy looks at the mind of Russell Kirk and how the horrors of war led to the birth of American conservatism.

Twenty-first century scientists have described their collaboration with the remarkable thirteenth-century polymath Bishop Grosseteste in exploring some of the secrets of the rainbow.

Christopher Howse tells us what the tiny church of St Peter’s, Charney Bassett in Oxfordshire has in common with St Mark’s in Venice.

Alex Massie looks cold and hard at whether the Conservatives really could become the second-largest party at the upcoming Scottish Parliament elections.

After ninety years and comprising twenty-one volumes, the Oriental Institute’s dictionary of the Akkadian language has been completed.

The Irish Arts Review examines the curious case of Dublin Airport’s original terminal — a design far ahead of its time but the origins of which are murky.

If prices as well as almost every opinion poll show the public prefer traditional-looking homes, then why doesn’t the market respond by building them?

And finally, Margaret Thatcher’s former home in London is on the market.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Gellner’s Prague December 19, 2024

- Monsieur Bayrou December 18, 2024

- Dempsey Heiner, Art Critic December 17, 2024

- Vote AR December 16, 2024

- Articles of Note: 12 December 2024 December 12, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories