Christmas

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Christmas Tree

Christmas 2021

A Metropolitan Christmas

I suppose Whit Stillman’s ‘Metropolitan’ is not strictly speaking a Christmas film but Yuletide is as good a time as any to watch the most Upper-East-Side movie ever to make the silver screen.

It includes a scene (clip above) from the Service of Nine Lessons and Carols at St Thomas, Fifth Avenue, which to my mind is the best carol service in New York. It’s even better when followed by a few drinks at the University Club one block up.

Wednesday 27 January

– Margaret Beaufort was one of the greatest women England ever produced, but her legacy has been plagued by misogyny combined with Protestant suspicion of her Catholic piety. Leanda de Lisle delves into the question of whether she was a hero or a villain.

– Speaking of powerful women, James Panero’s examines the monument to Joan of Arc on New York’s Riverside Drive. The artist was a female sculptor, Anna Hyatt Huntington, whose statue of El Cid in the forecourt of the Hispanic Society on Audubon Terrace is one of the finest sculptural arrangements in the New World.

– Lent is about to stare us in the face, but so far as I am concerned we are allowed to wallow in Christmas cheer until Candlemas comes on 2 February. Dr John C Rao (of St John’s University and the Roman Forum) offers us a reflection on the Christmas Crèche and its origins as Saint Francis’s giant “F.U.” to Cathar heretics, while putting the thinking behind that great saint’s actions in a modern context.

– It’s good to see neglected favourites receive a bit of unexpected attention. One such is the Irish writer George Russell, more often known by his pen name ‘Æ’. The Irish Ambassador to Great Britain, Dan Mulhall, begins a series on Irish writers and 1916 by looking at Æ in the context of the Rising.

One project that TCD or UCD – or anyone for that matter – needs to take on is digitising the entirety of The Irish Statesman, the journal mostly edited by Russell which presented a fascinating counterpoint to the more common narratives, first in 1919/20 and then from 1922 to 1930.

– And finally, some Goethe love from The New Yorker’s Adam Kirsch.

Happy Christmas

Happy Christmas

and a

Blessed New Year

I wish all our readers the very best for this Christmas season and I hope we will all enjoy innumerable blessings in this coming year.

For unto us, a Child is born…

a very happy and blessed

Christmas

The Queen’s Christmas Message 2007

Available here at YouTube.

Christmas

Corregio, Nativity

Oil on canvas, 101″ x 74″

1528-30, Gemäldegalerie, Dresden

Who with His life, the world to save,

All honor, power, glory, Thine,

and in Thy Heart our souls do bind.

a very merry and blessed Christmas.

Drink Audit Ale in Heaven With Me

I pray good beef and I pray good beer

This holy night of all the year,

But I pray detestable drink to them

That give no honour to Bethlehem.

May all good fellows that here agree

Drink Audit Ale in heaven with me,

And may all my enemies go to hell!

Noel! Noel! Noel! Noel!

May all my enemies go to hell!

Noel! Noel!

WITH THESE SIMPLE and lovely lines, Hilaire Belloc superbly expressed the esprit de Noël of the Christian curmudgeon. It amounts, more or less, to “Rend honor to the Holy Child, and to hell with the rest”.

His Lines for a Christmas Card are obviously meant in a jovial and light-hearted spirit (naturally, we would not wish Hell on any poor soul) and are completely intelligible but for this curious line: “May all good fellows that here agree / Drink Audit Ale in heaven with me”. What on earth is Audit Ale?

Before the Reformation, the English year was a calendar of feasts, festivals, and holidays — holy days, even. Four of these holy days, spaced fairly evenly throughout the year, were marked for such things as the collection of rents and the paying of feudal tributes. These four were Lady Day (March 25, the Feast of the Annunciation), Midsummer Day (June 24, the Feast of St. John the Baptist), Michaelmas (September 29, the Feast of St. Michael the Archangel), and Christmas (December 25, of course, the Feast of the Nativity of Christ).

Now, events such as the collection of fees and taxes and the giving of feudal tribute tend towards the dour, and so often a feudal lord would have a special ale brewed for these occasions, to ensure a certain amount of merriment among the commonfolk once their tribute had been paid and the burden lifted. This tended to be called ‘audit ale’, since it was brewed around the time of audit.

They were not, you will be happy to learn, the only seasonal brews around. There was ‘leet-ale’ for when the manorial court, or court-leet, convened, and there was Whitsun-ale for Whitsuntide, and there were church-ales which went towards the upkeep of the parish church and alms for the poor. Indeed, in village of Sygate in Norfolk, there is an inscription on the gallery of the church which reads:

And give us good ale enow . . .

Be merry and glade,

With good ale was this work made.

Also, interestingly, the very word ‘bridal’ comes not from the -al suffix English developed up from Latin, but rather from the Old English brýd-ealo: bride-ale or wedding-ale.

With the advent of Protestantism — and most especially the Puritan variant thereof — feasts, seasons, and other joviality generally became frowned-upon. England was forced to be less English, as the monotonous bores took over.

Still, remnants of the feasts and seasons remained. Lady Day was the first day of the year in Great Britain and its empire until 1752, when the Gregorian calendar was finally adopted. Similarly, the fiscal year in the United Kingdom begins on April 6 because that day in the Gregorian calendar corresponds to Lady Day in the old Julian calendar.

In Oxford and Cambridge, meanwhile, colleges still brewed special ales for the time when grades were released; either to celebrate the achievement or to soften the blow. These brews kept the old moniker of ‘audit ales’ and Belloc most likely uses the term in this derivation. Even in my own time at St Andrews we often sipped home-brewed ale from ancient, battered pewter tankards, though we rarely needed the excuse of holy days to continue the tradition.

In Oxford and Cambridge, meanwhile, colleges still brewed special ales for the time when grades were released; either to celebrate the achievement or to soften the blow. These brews kept the old moniker of ‘audit ales’ and Belloc most likely uses the term in this derivation. Even in my own time at St Andrews we often sipped home-brewed ale from ancient, battered pewter tankards, though we rarely needed the excuse of holy days to continue the tradition.

So this Yuletide perhaps you will consider home-brewing, and brew a special ale for the festal season now that the penetential time of Advent is passing. But, if you’re otherwise engaged, head into town and make sure to have a beer, and raise your pint to that Wondrous Babe whose birth brings us such mirth and cheer.

Christmas Book List

Mr. and Mrs. Peperium over at Patum Peperium asked a few of their genial friends to come up with a Christmas book list, and we were more than happy to oblige. Interestingly enough, the only overlap was Guy Stair Sainty’s giant two-volume opus, which was both on my list and on Fr. M.’s list. I have reproduced my list below for your perusal.

Well, first up, the books you can’t even get yet, not because they’re out of print but, rather, because they’re not exactly in print yet.

Well, first up, the books you can’t even get yet, not because they’re out of print but, rather, because they’re not exactly in print yet.

The Dangerous Book for Boys by Conn and Hal Iggulden has proved a roaring success amongst discriminating readers in the British Isles. The nifty book is basically a handbook for life, describing in detail how to win at conkers and learn the rules of cricket as well as providing information about major battles of history, NATO’s phonetic alphabet, the golden age of piracy, and that trickiest of all subjects:girls. The book’s out in Britain, Australia, and New Zealand, we North Americans will have to wait until May of next year.

Another book the Brits have already is Michael Burleigh’s Sacred Causes: The Clash of Religion and Politics from the Great War to the War on Terror, the sequel to Burleigh’s brilliant Earthly Powers: The Clash of Religion and Politics in Europe from the French Revolution to the Great War. In the first book, Burleigh brilliantly outlined the “long nineteenth century” as historians call it, depicting in detail the interplay between faith, reason, and power on the Mother Continent. Sacred Causes promises to bring us from the First World War all the way to the current so-called “War on Terror”, and we expect it will be done with the same precise, detailed, though occasionally light-hearted spirit which Burleigh has mastered. The book will be available on these verdant shores from March of next year.

While we’re traveling across the Atlantic, why not explore the British roots of our American society? In America’s British Culture, the late great Russell Kirk explores the Britannic foundations of the core of American culture and civilization. The book’s probably out of print, but can nonetheless be found here and there, and if not to purchase then there’s always the local library to try.

Far more perilous than a voyage cross the Atlantic is that most worrisome, tiresome, and pedantic of journeys: crossing the channel. To Belgium, or perhaps we should say “Belgium”, for after reading Flemish patriot Paul Belien’s A Throne in Brussels: Britain, the Saxe-Coburgs and the Belgianisation of Europe you will find the mere concept of “Belgium” repugnant. I picked up a copy of A Throne in Brussels and decided to give it a whirl despite finding the book’s title mostly uninteresting. After reading it, I also found the subtitle a little misleading. What Belien actually gives us is an overview of the history of “Belgium” which is both succinct and thorough, mostly focusing on the Belgian monarchy and its deep influence on the formation of this “nation” half-French and half-Dutch. It makes for a fascinating read of disgrace and debauchery as we’re told of the disgusting actions of, firstly the various kings of Belgium from the creation of the country ex nihilo in 1830, and then of astonishing Belgian cowardice and collaboration in the First and Second World Wars. However all this pales in comparison to the most telling, and the most disturbing, part of the book which tells us about modern, post-war Belgium. I will not reveal it’s contents but is truly, truly frightening. The point Belien posits as the crux of the book is this: I’ve told you about Belgium. Recall that the Eurocrats and their enthusiasts extol Belgium as the model for European unity; a single state in which communities of different blood and language live together in supposed harmony. If what I’ve written is true, then be afraid: be very afraid. And you will be.

Moving across the Continent, we stumble upon dear old darling Austria. The late Gordon Brook Shepherd was a devoted admirer of the Austrian people and nation, and this is exhibited in a number of the fine, well-crafted books he wrote. The Last Hapsburg is a very good biography of the Blessed Emperor Charles of Austria-Hungary, the last to rule over that many-peopled realm. It reads as a chronicle of simultaneous hope and decline, and the chapters detailing the Emperor’s two attempts to regain his Hungarian throne are action-packed and read like a spy thriller. Prelude to Infamy, meanwhile, deals with that last great figure of Austrian tradition and reaction, Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss. Brook Shepherd gives a splendid overview of Dollfuss’s early life and upbringing, his rise to power, and his eventual downfall at the hands of Hitler’s henchmen. Both these books are well worth reading, but I am also intrigued by the title alone of Brook Shepherd’s biography Between Two Flags: The Life of Baron Sir Rudolf von Slatin Pasha, GCVO, KCMG, CB, on which I have not yet been able to lay my hands.

Travelling deep within Europa’s belly are Patrick Leigh Fermor’s chronicles of his journey through Ruritania at the young age of twenty-two in the period between the wars when a great deal of the old order still remained. This meandering tramping trip, from London to Constantinople, is retold to us in Sir Patrick’s A Time of Gifts, considered a classic in the travel genre, and Between the Woods and the Water.

On his journey, Fermor came across a number of Europe’s aristocrats, nobility, and titled gentry. No doubt many-well, all really-of the honours and orders which bedecked their chests can be found in Guy Stair Sainty’s brand spanking new World Orders of Knighthood & Merit, out this year from Burke’s Peerage. The two volumes weigh in at twenty pounds imperial, containing two thousand pages and yours for a mere $375.

Cheaper, smaller, and infinitely more full of vim and moxie, however, is the delightful little picture book Simple Heraldry Cheerfully Illustrated by Sir Iain Moncrieffe of That Ilk, with truly cheerful illustrations by Don Pottinger. Both Moncreiffe and Pottinger served Her Majesty in the Court of Lord Lyon, Scotland’s heraldic authority, and the book is chock-full of delightful little explanations of the various aspects of heraldry, simplified and in digestible form.

But rememeber man that thou art dust and unto dust thou shalt return. If you’re lucky, that dust will be guarding the covers of the splendid Very Best of the Daily Telegraph’s Books of Obituaries which contains myriad tales of those individuals whose lives have been compacted onto the obituary page of Great Britain’s quality daily. Even more interesting is the more specific Daily Telegraph Book of Military Obituaries, containing various anecdotes of mess, ball, parade ground, and battlefield. How sad are the days when the only place one reads of class, dignity, and wit are the obituary pages! Or, as a friend puts it rather more alarmingly: every day more and more war veterans die off, while more and more products of government schools are unleashed into the world.

Yet our end ought to be a cheerful one, so catch up with that Grand Old Man who has since gone to join the Choir Invisible. The brilliant writings of Peter Simple are collected in a number of different volumes, most notably Peter Simple’s Century, which I warmly encourage the reader to purchase at the nearest opportunity. Better yet, make it two and forward one to me.

Bully!

The Feast of the Nativity

A very happy and blessed Christmas to you all!

Christmas Eve 1886

It was on this evening in 1886 that two souls experienced a profound conversion. Thérèse Martin, or Thérèse of Lisieux as she is now known, wrote of it in her spiritual biography, recounting: “On that luminous night, Our Lord accomplished in an instant the work I had not been able to do during years.”

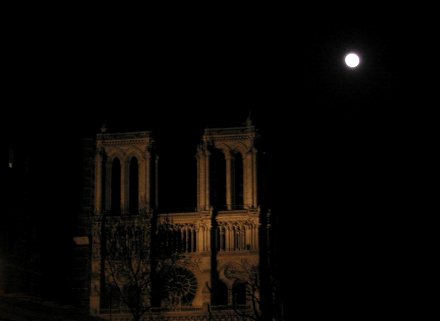

At the same time, almost the same hour, a young man in his twenties, Paul Claudel stood in the Cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris and began his return to the church. He was later to become a diplomat, poet, writer, and exegist.

Well I could go on further about both, but Philip Zaleski describes the conversion of Thérèse in his recent article ‘The Love of Saint Thérèse’ in First Things whereas Paul Claudel’s conversion is described by Eric Ormsby on the first page of the Arts section in today’s New York Sun. So do some research yourself. There’s a vast kingdom out there waiting to be learnt.

A very happy and blessed Christmas to you all!

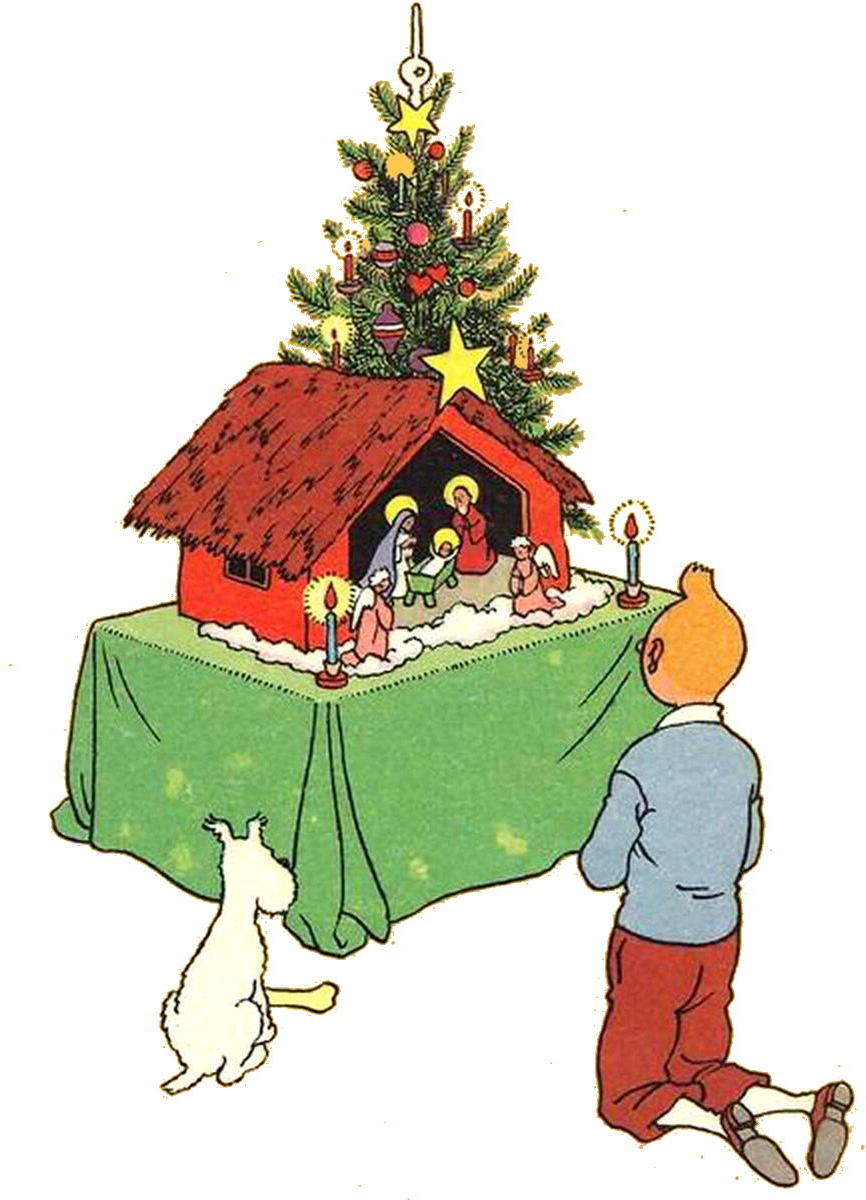

Christmas at Schloss Cusack

Ah, the fire burns, the tree is lit, and another Christmas is had amongst the fam.

Photos taken with my brand new digital camera. It replaces the one which was lost amidst the chaos of the 2003 Kate Kennedy Club May Charity Ball. Drowned in vodka.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Gellner’s Prague December 19, 2024

- Monsieur Bayrou December 18, 2024

- Dempsey Heiner, Art Critic December 17, 2024

- Vote AR December 16, 2024

- Articles of Note: 12 December 2024 December 12, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories