Cecil Rhodes

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

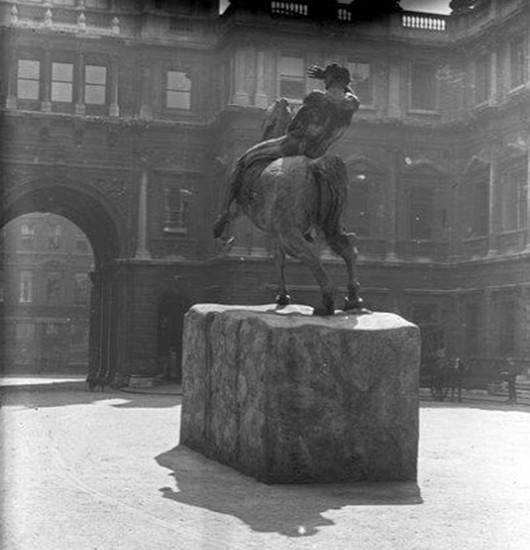

Physical Energy

I came across it by surprise one day, walking through the park. It was almost eerie — all the more so for being unexpected. George Frederic Watts’s sculpture “Physical Energy” was well known to me when I lived in South Africa as it graces the Rhodes Memorial in Cape Town — a rough Greek temple staring out northwards into the vast continent of Africa, as Rhodes himself liked to do.

Unknown to me, another cast of the statue was made and given to the British government, which placed it in Kensington Gardens. It was this copy I stumbled upon while traversing the park to Lily H’s drinks party in the garden of Leinster Square.

It is one of the most aptly named sculptures I can think of, as there is a raw brutish physicality to it, and somehow a sense of tremendous force, power, and energy. Watts was primarily a painter, so that he achieved this great work of sculpture is all the more remarkable. I don’t actually like it: there is something uncomforting and almost vulgar about it, or perhaps just taboo. (Like Rhodes himself.) But it is amazing all the same.

While “Physical Energy” is primarily associated with Cecil Rhodes it was not commissioned in his honour. Watts conceived it in 1886 after having done an equestrian statue for the Duke of Westminster. The first cast wasn’t made until 1902 and was exhibited at the Royal Academy for the first time in 1904 (above).

From there it made its way to Cape Town where it stands today a vital component of the monument to Rhodes. (It even features as the crest on Rhodes University’s coat of arms.) The second cast from 1907 is this one that sits in Kensington Gardens, while a third cast from 1959 now sits beside the National Archives of Zimbabwe in Harare.

This year the Watts Gallery in Surrey commissioned a fourth cast to commemorate the two-hundredth anniversary of the artist’s birth — and that cast now flaunts its bronze in the courtyard of the Royal Academy. It remains on view until the Cusackian birthday in March 2018.

A thoughtful leader

As newspapers go, the Feudal Times and Reactionary Herald is devilishly difficult to obtain. Its coverage of internal squabbles within the Marxist-Lefebvrist faction of the Communist Party of Great Britain makes for compelling reading and it is likewise to be thanked for its sensitive reporting on the goings-on of various disenfranchised Indian princely families. Alas, I have never discovered whether it is possible to subscribe to this illustrious periodical, and a visit to the City of London address printed on its editorial page revealed only that the building had been bombed out during the Blitz and more recently redeveloped into a giant postmodern office block housing ‘management consultants’.

As is often the case in times of difficulty, it is not in the metropole but in the periphery one finds comfort. I am currently enjoying a few days in Wexford town (or Veisafjǫrðr as the Feudal Times & Reactionary Herald would doubtless call this old Viking settlement in Ireland). This very day I was enjoying a delicious pub lunch — stuffed chicken wrapped in bacon with peas and mash all united by a gravy of optimal viscosity accompanied by a locally brewed Schwarzbier — when I was delighted to discover next to me a copy of the illustrious title left by a previous punter. A few weeks old and already well-thumbed, it nonetheless included this thoughtful editorial regarding the recent Rhodes controversy in Oxford which our readers might, despite its pretentious prose, find interesting:

Ex Africa semper aliquid novii a Roman of old once noted. We have recently and from many quarters heard much criticism of Mr Ntokozo Qwabe — a Rhodes scholar from the late lamented Union of South Africa — concerning his call for the removal of the statue of Mr Cecil Rhodes (quondam Prime Minister of the Cape of Good Hope) from the High Street frontage of Oriel College, an institution much beloved by many of the readers of this newspaper.

As Mr Qwabe is one of those currently enjoying the fruits of Mr Rhodes’s rather typical largesse, he has doubtless left himself open to accusations of hypocrisy and ingratitude. Nonetheless, we believe a certain lassitude and forgiveness is called for in this case as recent utterances pouring forth from his loquacious tongue have proved more amenable hearing to ear-trumpets both feudal and reactionary. For we are informed the young scholar has a new target in his sights: the tricolour flag of the dreaded French Republic. Mr Qwabe has called for it to be banished from the streets and quadrangles of both town and university, deriding this “violent symbol” of a republican regime that has “terrorised innocent lives”. Such a forceful allusion to the regicides of 1793 is to be welcomed firmly.

True to their typical form, the tweeded, begowned, and enscarfed undergraduates of Oxford’s colleges have taken up Mr Qwabe’s plea. Already the blue-white-and-red flag which until recently hung from the Pierre Victoire restaurant in Little Clarendon St has been replaced by a lily banner. It is regrettable, though, that a screening of ‘Le roi danse’ at the School of Modern Languages resulted in intermittent street violence between roving bands of rival Legitimiste and Orleaniste students, egged on by Bonapartist townsfolk from working-class enclaves in Jericho and Cowley. (The biretta of an innocent Oratorian is believed to have been knocked off in the ensuing melee.)

Mr Qwabe may have arrived on these shores with plans for revolt and ‘transformation’ but it is clear that Oxford is having its usual desired effect on this bright young man. Tumult is giving way to torpor, and doubtless this Rhodes scholar will return to the happy land of the assegai and the rondavel a good deal more broad-minded and reactionary. We wish him well.

The Epiphany 6 January 2016

Architectural historian Gavin Stamp argues that if Rhodes really was such a vicious baddie as his opponents claim, why stop with just removing his statue?

South African academic and Rhodes scholar R. W. Johnson has compared the campaign to remove Rhodes statues to ISIL’s destruction of antiquities in the Middle East while clerical commentator Fr Alexander Lucie-Smith recalls the damnatio memoriae.

Most interesting perhaps is the treatment of Rhodes not in the ivory towers of Oxford or Cape Town but in the land that once bore his name. Rhodes’s grave still lies in a prominent spot in the Motopos, but even President Robert Mugabe is against exhuming him.

From the Telegraph:

The last time that a call was made for the grave in the Matopos to be exhumed, Middleton Nyoni, then Town Clerk of Bulawayo, offered a telling response. “It is the Taliban who destroy history – and I am not a Taliban,” he declared. “After Rhodes’s grave, who is next?”

When Rhodesia became Zimbabwe in 1980, the city fathers of Bulawayo shifted Rhodes’s statue from the town centre to the town museum, while covering up the plaque commemorating his indaba with the chiefs of the Matabele. But in 2010 the city council voted to uncover the plaque while last year the Zimbabwean playwright Cont Mhlanga provocatively suggested returning Bulawayo’s statue of Rhodes to its former place of prominence.

U.C.T. has dumped Rhodes – though he remains elsewhere on Table Mountain – and his statue is still at Oriel… for now.

– This time last year, Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry asked if the Christian revival was starting in France. My pilgrimage to Chartres provided me with evidence that the faith across the Channel is deep, strong, and growing.

Now, looking forward to the year ahead, P.E.G. notes that Catholic France used to be old and rural — now it is young and urban: “In the major cities, all the churches are full on Sunday morning, something unthinkable even 10 years ago.”

– Former CIA agent Philip Giraldi visits Russia for the first time.

— All across the world, evidence shows that poverty is dropping dramatically. Why then, Fraser Nelson asks, is it so hard to believe?

Bicycle polo at the Wellington Monument in the Phoenix Park, 1938.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories