Catholicism

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Notes of the Netherlandic Church II

Archbishop Eijk chooses tradition-friendly priest as his cathedral rector

Fr. Harry Van der Vegt

The Archbishop of Utrecht & Primate of the Netherlands, Wim Eijk, has chosen a priest well-known for friendliness to traditional Catholics as the rector of his own cathedral. It was announced recently that Father Harry Van der Vegt is to be appointed rector of the Cathedral Church of St. Catherine in Utrecht, effective January 1, 2010. The priest will also be pastor of the Augustinuskerk and of St. Willibrord’s (which was the subject of the last Dutch church update).

Erik van Goor, of the Dutch periodical Bitterlemon, describes Fr. Van der Vegt as a “quiet but sturdy peasant’s son”. In the face of opposition from Modernist clergy and laity, Fr. Van der Vegt has been known to keep his cool, van Goor says. “Without making a political game of it, without showing any sign of reduced loyalty to the Church as it exists in the Netherlands, he remained quietly loyal to the tradition of the Church.”

“The appointment of Van der Vegt is actually a bit of a surprise”, notes one Dutch blogger, “because Archbishop Eijk is not really known as a major supporter of the old rite.” His Excellency was nonetheless responsible for normalizing the situation of the traditionalists of St. Willibrord’s Church in his diocese, mentioned previously.

Fr. Van der Vegt is currently serving the traditional faithful of Deventer in the province of Overijssel, and his new appointment will likely leave those people without a traditional mass for the time being. However, as Fr. Van der Vegt will be assuming control of St. Willibrord’s, the two FSSP priests currently there will probably be reassigned. The two currently travel all across the Low Countries, offering masses in Amsterdam, Bruges, Rotterdam, and elsewhere.

Parishioners at St. Willibrord’s, meanwhile, hope the new priest will say the extraordinary form at a more advantageous hour; it is currently said each Sunday at 5:30 in the evening.

Foundation ‘Ecclesia Dei’ Delft Releases 2009 Report

The Foundation ‘Ecclesia Dei’ Delft has released its latest report on the state of tradition in the Netherlandic church. ‘Ecclesia Dei’ is a group of Catholic faithful attached to the traditional liturgy as codified in the 1962 missal, and exists for the promotion of Catholic orthodoxy and specifically the liturgical tradition of the Church. In gauging the response to Benedict XVI’s motu proprio Summorum Pontificium, the report finds that “the Dutch Bishops Conference did not define a common policy concerning the implementation of the motu proprio.” The general attitude of the bishops is described as one of extreme passivity, “discouraging requests, ignoring the traditional liturgy, and keeping the faithful in ignorance of the motu proprio by a lack of information combined with disinformation about the traditional Latin liturgy.”

The report posits that bishops are primarily “afraid of the opposition by the modernist-infected priests and/or parish boards.” Many ordinary orthodox Catholics in the Netherlands are disillusioned with the strident Modernism that has infected much of the local church, and the bishops are said to fear “polemics” and “discord” even though, the report states, “they have not undertaken any measures to solve these problems for many years”.

On the teaching of the traditional liturgy in Dutch seminaries, the report confirms that instruction about the extraordinary form is almost nonexistent.

“However, since March 2009 and against the opposition of a number of priestly staff members at the seminary of St. Jan in ‘s-Hertogenbosch, a course about the theology of the traditional Latin liturgy has been given, but only because some of the seminarians claimed to have the right to it and showed a letter from the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei.”

“As a result, 8 of the 12 seminarians now attend a private traditional Latin Mass three days a week at that seminary, despite the opposition.”

“In some diocese the situation has been improved in the first year of the motu proprio only by the initiatives of individual, relatively young priests.”

Some priests have attended German-organised training sessions, while others have received instruction from the FSSP priests in Amsterdam.

“Most of these priests are celebrating the traditional Latin liturgy in private and some even weekly in public now.”

As for the news of the specific dioceses of the Netherlands, much has already been written about the primatial see of Utrecht. In the Diocese of Haarlem-Amsterdam, Bishop Punt is prepared to grant FSSP a personal parish, from which the priests can work all over his diocese. Talks are ongoing. In other dioceses, however, foot-dragging, lip service, or ignorance of requests have been the norm.

Our Cardinal & Our Seminarians

His Eminence Keith Patrick O’Brien, Cardinal Archbishop of St Andrews & Edinburgh, Primate of Scotland, has a wee chat with a triumvirate of seminarians from the Pontifical Scots College, Rome at the Holy Father’s weekly general audience. St Andreans (or at least Old Canmoreans) will recognize the ginger chap at right, attentively listening to the Cardinal’s words. I caught up with him in August when he had just a week to go before heading to seminary.

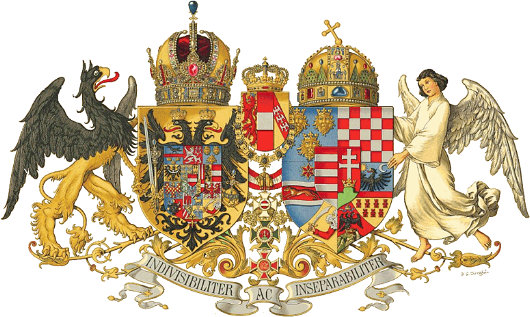

Argentines Recall Blessed Emperor

An Argentine correspondent informs us that the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass was offered on October 28th at the Church of St. Boniface, the German-speaking parish of the Archdiocese of Buenos Aires, to commemorate the fifth anniversary of the beatification of Blessed Charles, Emperor of Austria and Apostolic King of Hungary. The mass was organized by Viscountess Huges Stier de Saint Jean (née Princess Isabelle Auersperg-Breunner), whose mother was a descendant of the Emperor Franz Joseph through his daughter Valerie. The Mass was offered in Spanish and German, with the prayers of intention read in those languages as well as Hungarian, Slovak, Ukrainian, Croatian, and Italian.

Category: Charles of Austria

Bertie Monument Unveiled in Malta

During Fra’ Andrew Bertie’s reign as Guardian of the Poor of Jesus Christ, the “of Malta” at the end of “the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem of Rhodes and of Malta” was not a mere historical anachronism. The Prince & Grand Master had a house in Malta where he attended to his cultivation of oranges (the old Grand Master’s Palace in Valetta is now the Presidential Palace of the Maltese Republic). “A friend of Malta,” a recent statement from the Maltese knights of the Order states of Fra’ Andrew Bertie, “his love for Malta and the Maltese peoples’ affection for him originated the inspiration to this wonderful project, to erect a befitting marble lapidary in his memory.” This summer Fra’ Matthew Festing, successor to Fra’ Andrew as head of the Order of Malta, travelled to the Mediterranean island to unveil the Bertie Monument at Casa Lanfreducci, the Order’s Maltese seat. (more…)

Benedict in Bohemia and Moravia

THE HOLY FATHER, Pope Benedict XVI, recently travelled to the Czech Republic in a journey he described as “both a pilgrimage and a mission.” The ancient land of Bohemia was once at the very center of Christian civilization. It was from here that the brother saints Cyril and Methodius launched their mission to convert the Slavic world. From Prague, the realms of the Přemyslid and then Luxembourg dynasties were ruled, followed by the most illustrious house of Hapsburg. Oh to have been in Prague under the reign of the Emperor Rudolf II! With his mysterious court of astrologers and magicians and his cabinet of curiosities. With Arcimboldo, Spranger, Heintz, and Hans von Aachen putting paint to canvas, Giambologna and de Vries sculpting, while Kepler and Tycho Brahe searched the night skies. Centuries later, long after the nucleus of Hapsburg power had moved to Vienna, it was to Prague that the Emperor Ferdinand came following his abdication and remained until his death in 1875.

But of course there is the other Prague — the city of heresy, rebellion, and warfare. (more…)

Notes of the Netherlandic Church

Willem Jacobus Eijk, Primate of the Netherlands

THE ANCIENT FORM of the Roman rite has returned to weekly use in Utrecht, the primatial see of the Netherlands. Under the guidance of Wim Eijk, Archbishop of Utrecht, the Church of St. Willibrord has introduced a weekly Tridentine liturgy each Sunday at 5:30 pm, to complement the 10:30 am Mass in Latin in the Ordinary Form. (Previously the old rite was offered only once monthly). The Extraordinary Form will be offered by Fr. A. Komorowski & Fr. M. Kromann Knudsen, both of the Priestly Fraternity of Saint Peter (FSSP, or Priesterbroederschap Sint Petrus in Dutch). St. Willibrord’s is a brilliant example of the nineteenth-century revival of gothic architecture, and the concurrent revival of Dutch Catholicism. Yet the parish was also emblematic of the Dutch church’s implosion in the 1960s & 70s. This beautiful, polychromatic monument to God was deconsecrated in 1967, and the diocese planned on demolishing the building. It was later sold, however, and occupied by an Assumptionist priest who continued saying the older form of mass. Joseph Luns, sometime NATO secretary-general and Dutch foreign minister, was a supporter of the apostolate at St. Willibrord’s.

The recently installed archbishop was keen to regularize the former parish’s situation, and erected it as a non-territorial parish under the auspices of the Vereniging voor Latijnse Liturgie (Association for Latin Liturgy) which promotes Latin in both the ordinary & extraordinary forms of the liturgy. The parish newsletter now proclaims that, at St. Willibrord’s, “all masses are once again celebrated ‘ad orientem'”, and both Sunday masses are accompanied by Gregorian chant. The church also revived, starting in 2002, the Procession of the Relics of St. Willibrord, which is held during the annual festival that opens the cultural season in Utrecht, in order to expose the tradition to a wider audience. (more…)

Life of St. Hildegard Hits the Silver Screen

But is it the Hildegard of historical fact or modern fantasy?

THE LIFE OF Saint Hildegard von Bingen — the Benedictine nun, writer, scientist, physician, and poet perhaps best known as a composer — has been brought to the screen in a new German-produced film. “Vision – Aus dem Leben der Hildegard von Bingen” was released in Germany & Austria in September and may receive a wider European release in 2010. From the voluntary confinement of the cloister, this woman corresponded with the Emperors Lothair II and Frederick Barbarossa, the popes Eugene III and Anastasius IV, the great patron of art Abbot Suger, and of course the great Cistercian reformer St. Bernard of Clairvaux. Hildegard was authorised to go on four preaching tours, and her Ordo Virtutum was the first allegorical morality play of the medieval period. She even invented a demi-language, Lingua Ignota (“unknown language”), and created an alternative alphabet in which to write it. (more…)

A Wanderer Anecdote

“It’s too easy for theological writers to sling around Abstractions with Capital Letters, as if with each stroke of the pen they’re tapping into Plato’s realm of changeless, ineffable Forms. Or at least that they’re writing in German, where all nouns start with caps.”

So begins John Zmirak, who tells a delightful story about one of America’s premier Catholic newspapers.

“A friend of mine used to write weekly for the estimable investigatory journal The Wanderer. Founded by German-Catholic immigrants, it was published auf Deutsch well into the twentieth century.

As my friend recalled, ‘The editors were, I think, waiting for the rest of the country to catch up with them. At last they admitted that this was unlikely, and agreed to translate the paper. But they kept on as their typesetter someone named Uncle Otto, who for years insisted on capitalizing every noun.’”

The He/She/It Whatnot

Seraphic Spouse held a poll on what pronouns people prefer using when referring to God: 1) He/Him/Himself, 2) he/him/himself, or 3) avoiding male pronouns. The unsurprising results were 89% for the traditional He/Him/Himself, 9% for the New York Times option of he/him/himself, and just over 1% for the radical choice of avoiding male pronouns altogether.

“Some readers may be wondering why this matters so much,” saith Lady Seraphic. “The answer is that people do care about these things, and I don’t want any reader of the book to feel alienated. I want everyone who might read such a book to feel embraced. And just as a now-elderly generation of Catholic women felt alienated by masculine language for God, younger generation of Catholics want to conserve the great respect for God now lacking in secular society.”

Over at Epigone’s Eloquence, meanwhile, Turgonian watched a biased BBC documentary (those three words go together so often!) on Gnosticism and was inspired to write ‘Why God is a He’, looking to the Monologion of St. Anselm for the answer.

“St. Anselm has previously established that God is Spirit, not a body, and that it is therefore nonsensical to say that He is a man or a woman. He has also shown that it is reasonable to believe that God exists as Father and Son (the Holy Spirit will come later in the book). But, he asks, why Father and Son, rather than Mother and Daughter? Why not call them by feminine names?” Read on to find out.

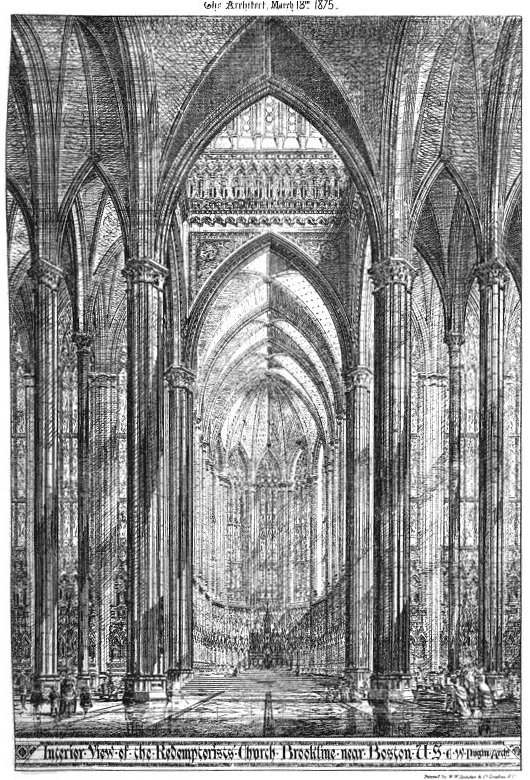

Unbuilt Pugin in Boston

Unbuilt proposal for a Redemptorist church in Boston by Edward Welby Pugin, eldest son of Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin.

‘Dim Tim’ & Chick-lit Bagshawe go twit for tat over “slobbering” devotees of Thérèse

Tim Cheetham, a Labourite councillor in the legendary south Yorkshire town of Barnsley, has expressed his disdain for the enthusiasm his fellow countrymen and women have shown for the beloved Saint Thérèse of Liseux via the medium of Twitter: “With all those slobbering zealots kissing that glass case, I hope it has some mystical power to prevent swine flu.” As Catholic Herald editor Damian Thompson states, “That’s the authentic voice of 21st-century Labour.”

Louise Bagshaw, a “chick-lit” novelist, prospective Tory party candidate, and Woldingham old girl, wasted no time in responding. “Nice to describe faithful Catholics venerating a relic as slobbering zealots. Would you use such bigoted language about Muslims?”

Cheetham’s rather lame retort: “As the church has issued new guidlines [sic] about the conduct of ceremonies to protect against spreading disease, it needed saying.”

Bagshawe: “Labour’s anti-Catholicism is breathtaking sometimes.”

Damian Thompson continues:

Another tweet from Cheetham: “It’s not Bigotry to highlight the lunacy of dark age mysticism in the modern world.” Really? OK, then let me put you on the spot, councillor.

You say: “I will decry any faith that denies my right to question it in whatever form I wish.” Well, Muslims in Barnsley do object to the slightest criticism of their Prophet (who lived during the dark ages, as it happens) with his child wives and message of violence. But you’re a brave man, it seems. So go on: speak fearlessly and with your trademark withering disdain about the zealots in your own town.

Dim Tim later tried to backtrack by blaming the medium of Twitter for his own idiotic remarks.

To my knowledge, Barnsley’s not a town short on Catholics. Let’s hope those “slobbering zealots” make it to the polling place the next time the council’s up for election.

Thérèse Takes Britain by Storm

Relics of St Thérèse of Lisieux arrive in Britain for tour

The Guardian: Thousands wait at Portsmouth cathedral to see remains of St Thérèse

The Catholic Herald: The greatest saint of modern times

Thérèse of Lisieux portal

The Daily Telegraph: Relics of Carmelite nun St Thérèse on tour

St Thérèse of Liseux: who was she?

The relics and bones that bring us closer to God

BBC News: Saint’s remains arrive for tour

Reuters: Saint’s relics heading for Wormwood Scrubs

The Independent: Why are the relics of St Thérèse such a holy hit?

catholicrelics.co.uk

pray for us!

Wisconsin Baroque, Priests, and Paper Architecture

Matthew G. Alderman

Taken from: Dappled Things, Ss. Peter & Paul, 2009

MY FAVORITE BUILDINGS never got around to being built. Some, like Sir Edwin Lutyen’s majestic design for Liverpool Cathedral, fell victim to budget cuts and the vagaries of history. Others were consigned by good taste, or occasionally outright timidity, to competition honorable mentions, and still others, like numerous student proposals or visionary dreams—like Boulée’s alarming hemispherical cenotaph for Newton, or an imaginary papal palace in Jerusalem cooked up by one of the votaries of the Vienna Sezession—weren’t terribly serious to begin with, unfortunately.

Note that I say favorite buildings, my own personal favorites, rather than the best or the most beautiful. Lutyens’ and Boulée’s fantasies may cross into that sublime territory of beauty by the power of their imaginative vision, but so many of the others owe their charm to their dreamlike extravagances, their intriguing if perhaps incomplete answers. An architect’s education lies in gathering up such fragmentary answers for the questions he will face down the road from clients and patrons. And therein lies the lure, and the value, of paper architecture.

I, like most of my colleagues, spent much of my time in school devising such useful fantasies, sometimes grand, sometimes small. Yet, they were not castles in the air. Each, while often existing in something like the best of all possible worlds in terms of budget and client, was grounded by an actual site and the laws of nature.

The most elaborate of all was my thesis project. It was an imaginary American seminary for a very real religious order, the fast-growing Institute of Christ the King, Sovereign Priest. This new congregation, dedicated to evangelization through the beauty of art, music, and the traditional Latin Mass, started out in, of all places, Gabon in Africa, but its present headquarters lies in Tuscany, in a villa bursting at the seams with seminarians in formation. While their ranks are dominated by Germans and Frenchmen, the increasing number of American clergy and their recent erection of a number of apostolates scattered across the Midwest suggested that a seminary in the United States, if not planned, might at least make for a plausible student project. Also, they seemed to have adventurous taste. I have since developed a passion for the Gothic but my first love has always been the Italian baroque. Perhaps they might be open to its vigorous beauty.

I garnered an award for the end result, the Rambusch Prize for Religious Architecture, and my putative patrons wanted copies of my enormous presentation watercolors to hang on their office walls—though, of course, the seminary would forever remain unbuilt. Its gigantic scale—typical for a student project—put it outside budgetary reach, unless, as someone cheerfully quipped, Bill Gates converted. Yet, the design was logical, consistent, and helped hone design skills I use every day at my drafting board.

The notion for the seminary came shortly after my first real-life encounter with the Institute’s work. My friends and I were road-tripping through the hill country of central Wisconsin, thick with vivid fall colors, and had just come back from a serene, silent low Mass and a long, talkative, private tour of St. Mary’s Oratory in Wausau. The Institute had transformed from a bland Midwestern Gothic to a dazzling near-replica of a fourteenth-century Bavarian court chapel. Bill Gates or no, these priests think big. Since then, they’ve overhauled a historic church in downtown Kansas City, and they’re presently turning their American priory from a burnt-out shell in a borderline south-side Chicago neighborhood into something out of Counter-Reformation Rome, and I have no doubt they’re going to succeed. Lest these projects seem like archaeological transplants, they are in fact derived from a logical extrapolation from local Catholic culture—Chicago’s colorful Polish cathedrals brought back to their ultramontane source, or, as I had just discovered, Midwestern Gothic returned to its Germanic roots. (more…)

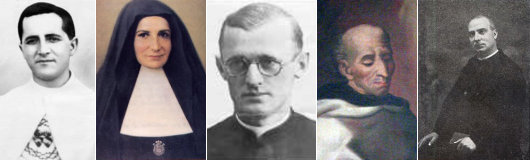

Recent Promulgations from the Holy See

Decrees recently promulgated in the Vatican move sixteen candidates for sainthood forward in their cause. The most famous of the twelve is the English cardinal & convert from Anglicanism, John Henry Newman (above, center). A miracle attributed to the intercession of Cardinal Newman has been accepted by the Congregation for the Causes of the Saints. The Congregation has also accepted individual miracles attributed to the intercession of: Blessed Cándida Maria de Jesús Cipitria y Barriola (above, second from left; 1845-1912), the Spanish founder of the Congregation of the Daughters of Jesus; the Servant of God Angelo Paoli (below, second from right; 1642-1720), an Italian Carmelite priest; the Servant of God Maria Alfonsina Danil Ghattas (1843-1927), a cofounder of the Congregation of the Sisters of the Most Holy Rosary of Jerusalem.

Eight martyrs were proclaimed in the recently-promulgated decrees: all of them of the twentieth century and all of them victims of totalitarianism. Fr. Teófilo Fernández de Legaria Goñi (below, far left) and four companions (all professed priests of the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary), as well as the diocesan priest Fr. José Samsó i Elías (below, far right), were all killed by the Communists in 1936 during the horrible persecution of the Church during the Spanish Civil War. Fr. Georg Häfner (above, far right), a German diocesan priest, was killed in the concentration camp of Dachau in 1942 under the Nazi regime. Bishop Zoltán Lajos Meszlényi (above, far left), an auxiliary bishop of Esztergom, was killed at Kistarcsa in Hungary by the Communist authorities in January 1953.

Proclamations of heroic virtue — the first step on the road to being recognised as a saint — were issued for: Fr. Engelmar Unzeitig (below, center; 1911-1945), a German priest of the Mariannhill missionaries; Anna María Janer Anglarill (below, second from left; 1800-1885), the Spanish founder of the Institute of Sisters of the Holy Family of Urgell; Maria Serafina del Sacro Cuore di Gesu Micheli (1849-1911), the Italian founder of the Institute of Sisters of the Angels; Teresa Manganiello (above, second from right; 1849-1876), an Italian laywoman of the Third Order of St. Francis.

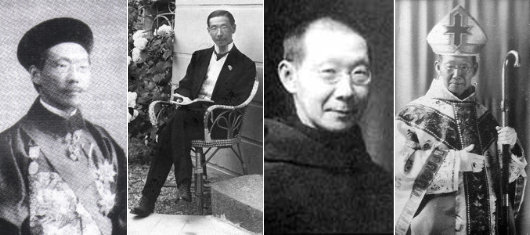

The Prime Minister of China who became a Benedictine Abbot

CHRISTIANITY HAS A LONG and varied history in China stretching over at least one-and-a-half millenia. The ancient country has even had Christian leaders, such as the Congregationalist founder of the Chinese Republic, Sun Yat-sen, and his Methodist successor, Gen. Chiang Kai-shek (head of the Kuomintang for nearly forty years). Still, until I read this fascinating story in the Catholic Herald I had no idea that there was a Prime Minister of China, Lou Tseng-tsiang (陸徵祥), who ended his days as a Benedictine monk by the name of Dom Pierre-Célestin. Lou was born a Protestant in Shanghai in 1871, but married a Belgian woman and eventually converted to Catholicism. Serving his country in the diplomatic arena, he accomplished extensive reforms of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, avoided becoming part of any of the various factions that divided the government, and was one of the founding members of the Chinese Society of International Law. Lou bravely stood up to the indignities imposed upon China through the 1919 Treaty of Versailles by refusing to sign the shameful document which sewed the seeds of future disaster.

Xu Jingcheng, Lou’s mentor and sometime Ambassador to the Court of the Tsars in St. Petersburg, instructed the up-and-coming diplomat that “Europe’s strength is found not in her armaments, nor in her knowledge — it is found in her religion. … Observe the Christian faith. When you have grasped its heart and its strength, take them and give them to China.”

After the death of his wife, Lou became a Benedictine monk at the abbey of Sint-Andries in Flanders, and was eventually ordained a priest in 1935. A decade later, Pope Pius XII — who cared deeply for the Church in China and finally settled the long-standing dispute over Chinese ancestor-honouring rituals in favour of the practices — appointed him titular abbot of the Abbey of St. Peter in Ghent. Sadly, the Chinese Civil War prevented Dom Pierre-Célestin from returning to China, and he died in Flanders in 1949.

The words of Lou’s mentor that Europe’s strength is her faith found recent confirmation from Professor Zhao Xiao, a prominent Chinese economist at the University of Science & Technology Beijing. Prof. Zhao, a member of the Chinese Communist Party, began studying the differences between the economies of Christian societies and those of non-Christian societies. As a result of his investigations, he argued that Christianity would provide a “common moral foundation” for China that would help the economy by reducing corruption, narrowing the gap between rich and poor, preventing pollution, and promoting philanthropy.

“A good business ethic or business morality,” Prof. Zhao says, “can provide for a type of motivation that transcends profit seeking. Why do people want to do business? The main goal would be to earn money. The purpose of a company is to maximize profits. But this can cause companies to look for quick results and nearsighted benefits. It can cause companies to disregard the means and earn money at the expense of destroying the environment, society and the livelihood of others, or endangering the entire competitive environment of the trade.”

“If my motivation for doing business is the glory of God, there is a motivation that transcends profits. I cannot go and use evil methods. If I used some evil methods to enlarge the company, to earn money, then this is not bringing glory to God. Therefore, this is to say that it [bringing glory to God] can provide a transcendent motivation for business. And this kind of transcendental motivation not only benefits an entrepreneur by making his business conduct proper but it can also benefit the entrepreneur’s continued innovation.” (more…)

Our Cardinal at the Oratory

His Eminence Keith Patrick O’Brien, Cardinal Archbishop of St Andrews & Edinburgh, at the Brompton Oratory for the Feast of St. John the Baptist this year.

(From the NLM)

Praying with the Kaisers

by JOHN ZMIRAK

INSIDECATHOLIC.COM

As I’m writing this column at the tail end of my first trip to Vienna, some of you who’ve read me before might expect a bittersweet love note to the Habsburgs — a tear-stained column that splutters about Blessed Karl and “good Kaiser Franz Josef,” calls this a “pilgrimage” like my 2008 trip to the Vatican, and celebrates the dynasty that for centuries, with almost perfect consistency, upheld the material interests and political teachings of the Church, until by 1914 it was the only important government in the world on which the embattled Pope Pius X could rely for solid support. Then I’d rant for a while about how the Empire was purposely targeted by the messianic maniac Woodrow Wilson, whose Social Gospel was the prototype for the poison that drips today from the White House onto the dome of Notre Dame.

And you would be right. That’s exactly what I plan to say — so dyed-in-the-wool Americanists who regard the whole of the Catholic political past as a dark prelude to the blazing sun that was John Courtenay Murray (or John F. Kennedy) might as well close their eyes for the next 1,500 words — as they have to the past 1,500 years.

But as I bang that kettle drum again, I want to set two scenes, one from a fine and underrated movie, the other from my visit. The powerful historical drama “Sunshine” (1999) stars Ralph Fiennes as three successive members of a prosperous Jewish family in Habsburg Budapest. The film was so ambitious as to try portraying the broad sweep of historical change — and, as a result, it was not especially popular. What historical dramas we moderns tend to like are confined to the tale of a single hero, and how he wreaks vengeance on the villains with English accents who outraged the woman he loved. “Sunshine”, on the other hand, tells the vivid story of the degeneration of European civilization in the course of a mere 40 years. The Sonnenschein family are the witnesses, and the victims, as the creaky multinational monarchy ruled by the tolerant, devoutly Catholic Habsburgs gives way through reckless war to a series of political fanaticisms — all of them driven by some version of Collectivism, which the great Austrian Catholic political philosopher Erik von Kuenhelt-Leddihn calls “the ideology of the Herd.”

From a dynasty that claimed its legitimacy as the representative of divine authority at the apex of a great, interconnected pyramid of Being in which the lowliest Croatian fisherman (like my grandpa) had liberties guaranteed by the same Christian God who legitimated the Kaiser’s throne, Central Europe fell prey to one strain after another of groupthink under arms: From the Red Terror imposed by Hungarian Bolsheviks who loved only members of a given social class, to radical Hungarian nationalists who loved only conformist members of their tribe, to Nazi collaborationists who wouldn’t settle for assimilating Jews but wished to kill them, finally to Stalinist stooges who ended up reviving tribal anti-Semitism. The exhaustion at the film’s end is palpable: In the same amount of time that separates us today from President Lyndon Johnson, the peoples of Central Europe went from the kindly Kaiser Franz Josef through Adolf Hitler to Josef Stalin. Call it Progress.

Apart from a heavily bureaucratic empire that spun its wheels preventing its dozens of ethnic minorities from cleansing each other’s villages, what was lost with the fall of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy? For one thing, we lost the last political link Western Christendom had with the heritage of the Holy Roman Empire. (Its crown stands today in the Imperial Treasury at the Hofburg, and for me it’s a civic relic.) Charlemagne’s co-creation with the pope of his day, that Empire had symbolized a number of principles we could do well remembering today: Principally, the Empire (and the other Christian monarchies that once acknowledged its authority) represented the lay counterpart to the papacy, a tangible sign that the State’s authority came not from mere popular opinion, or the whims of tyrants, but an unchangeable order of Being, rooted in divine revelation and natural law.

The job of protecting the liberty of the Church and enforcing (yes, enforcing) that Law fell not to the clergy but to laymen. The clergy were not a political party or a pressure group — but a separate Estate that often as not served as a counterbalance to the authority of the monarchy. No monarch was absolute under this system, but held his rights in tension with the traditional privileges of nobles, clergy, the citizens of free towns, and serfs who were guaranteed the security of their land. Until the Reformation destroyed the Church’s power to resist the whims of kings — who suddenly had the option of pulling their nation out of communion with the pope — no king would have had the power or authority to rule with anything like the monarchical power of a U.S. president. Of course, no medieval monarch wielded 25-40 percent of his subjects’ wealth, or had the power to draft their children for foreign wars. It took the rise of democratic legal theory, as Hans Herman Hoppe has pointed out, to convince people that the State was really just an extension of themselves: a nice way to coax folks into allowing the State ever increasing dominance over their lives.

A Christian monarchy, whatever its flaws, was at least constrained in its abuses of power by certain fundamental principles of natural and canon law; when these were violated, as often they were, the abuse was clear to all, and the monarchy often suffered. In extreme cases, kings could be deposed. Today, by contrast, priests in Germany receive their salaries from the State, collected in taxes from citizens who check the “Catholic” box. So much for the independence of the clergy.

The House of Austria ruled the last regime in Europe that bound itself by such traditional strictures, which took for granted that its family and social policies must pass muster in the Vatican. By contrast, in the racially segregated America of 1914, eugenicists led by Margaret Sanger were already gearing up to impose mandatory sterilization in a dozen U.S. states (as they would succeed in doing by 1930), while Prohibitionist clergymen and Klansmen (they worked together on this) were getting ready to close all the bars. As historian Richard Gamble has written, in 1914 the United States was the most “progressive” and secular government in the world — and by 1918, it was one of the most conservative. We didn’t shift; the spectrum did.

Dismantled by angry nationalists who set up tiny and often intolerant regimes that couldn’t defend themselves, nearly every inch of Franz-Josef’s realm would fall first into the hands of Adolf Hitler, then those of Josef Stalin. Today, these realms are largely (not wholly) secularized, exhausted perhaps by the enervating and brutal history they have suffered, interested largely in the calm and meaningless comfort offered by modern capitalism, rendered safer and even duller by the buffer of socialist insurance. The peoples who once thrilled to the agonies and ecstasies carved into the stone churches here in Vienna can now barely rouse the energy to reproduce themselves. Make war? Making love seems barely worth the tussle or the nappies. Over in America, we’re equally in love with peace and comfort — although we’ve a slightly higher (market-driven?) tolerance for risk, and hence a higher birthrate. For the moment.

Speaking of children brings me to the most haunting image I will take away from Austria. I spent a whole afternoon exploring the most beautiful Catholic church I have ever seen — including those in Rome — the Steinhof, built by Jugendstil architect Otto Wagner and designed by Kolomon Moser. An exquisite balance of modern, almost Art-Deco elements with the classical traditions of church architecture, it seems to me clear evidence that we could have built reverent modern places of worship, ones that don’t simply ape the past. And we still can. A little too modern for Kaiser Franz, the place was funded, the kindly tour guide told me in broken English, by the Viennese bourgeoisie. (Since my family only recently clawed its way into that social class, I felt a little surge of pride.) Apart from the stunning sanctuary, the most impressive element in the church is the series of stained-glass windows depicting the seven Spiritual and the seven Corporal Works of Mercy — each with a saint who embodied a given work. All this was especially moving given the function of the Steinhof, which served and serves as the chapel of Vienna’s mental hospital. (It wasn’t so easy getting a tour!) The church was made exquisite, the guide explained, intentionally to remind the patients that their society hadn’t abandoned them. Moser does more than Sig Freud can to reconcile God’s ways to man.

We see in the chapel the spirit of Franz Josef’s Austria, the pre-modern mythos that grants man a sacred place in a universe where he was created a little lower than the angels — and an emperor stands only in a different spot, with heavier burdens facing a harsher judgment than his subjects. No wonder Franz Josef slept on a narrow cot in an apartment that wouldn’t pass muster on New York’s Park Avenue, rose at 4 a.m. to work, and granted an audience to any subject who requested it. He knew that he faced a Judge who isn’t impressed by crowns.

As we left the church, I asked the guide about a plaque I’d seen but couldn’t quite ken, and her face grew suddenly solemn. “That is the next part of the tour.” She explained to me and the group the purpose of the Spiegelgrund Memorial. It stands in the part of the hospital once reserved for what we’d call “exceptional children,” those with mental or physical handicaps. While Austria was a Christian monarchy, such children were taught to busy themselves with crafts and educated as widely as their handicaps permitted. The soul of each, as Franz Josef would freely have admitted, was equal to the emperor’s. But in 1939, Austria didn’t have an emperor anymore. It dwelt under the democratically elected, hugely popular leader of a regime that justly called itself “socialist.” The ethos that prevailed was a weird mix of romanticism and cold utilitarian calculation, one which shouldn’t be too unfamiliar to us. It worried about the suffering of lebensunwertes Leben, or “life unworthy of life”–a phrase we might as well revive in our democratic country that aborts 90 percent of Down’s Syndrome children diagnosed in utero. So the Spiegelgrund was transformed from a rehabilitation center to one that specialized in experimentation. As the Holocaust memorial site Nizkor documents:

In Nazi Austria, parents were encouraged to leave their disabled children in the care of people like [Spiegelgrund director] Dr. Heinrich Gross. If the youngsters had been born with defects, wet their beds, or were deemed unsociable, the neurobiologist killed them and removed their brains for examination. …

Children were killed because they stuttered, had a harelip, had eyes too far apart. They died by injection or were left outdoors to freeze or were simply starved.

Dr. Gross saved the children’s brains for “research” (not on stem cells, we must hope). All this, a few hundred feet from the windows depicting the Works of Mercy. Of course, they’d been replaced by the works of Modernity.

We’re much more civilized about this sort of thing nowadays, as the guests at Dr. George Tiller’s secular canonization can testify. In true American fashion, our genocide is libertarian and voluntarist, enacted for profit and covered by insurance.

I will think of the children of the Spiegelgrund tomorrow, as I spend the morning in the Kapuzinkirche, where the Habsburg emperors are buried — and the Fraternity of St. Peter say a daily Latin Mass. As I pray the canon my ancestors prayed and venerate the emperors they revered, I will beg the good Lord for some respite from all the Progress we’ve enjoyed.

Blessed Karl I, ora pro nobis.

[Dr. John Zmirak‘s column appears every week at InsideCatholic.com.]

The Order of Malta in Peru

A correspondent of this site sends these images of the Order of Malta in Peru. The Order of Malta has a long history in Peru: Manuel de Guirior, 1st Marqués de Guiror and a knight of the Order (right, baptised José Manuel de Guirior Portal de Huarte Herdozain y González de Sepúlveda) was Viceroy of Peru from 1776 to 1780, having previously served the King of Spain as Viceroy of New Granada.

A correspondent of this site sends these images of the Order of Malta in Peru. The Order of Malta has a long history in Peru: Manuel de Guirior, 1st Marqués de Guiror and a knight of the Order (right, baptised José Manuel de Guirior Portal de Huarte Herdozain y González de Sepúlveda) was Viceroy of Peru from 1776 to 1780, having previously served the King of Spain as Viceroy of New Granada.

More recently, in 2008, this investiture (above) was presided over by Fernando de Trazegnies, Marquis of Torrebermeja, the former Dean of Law at the Catholic University of Peru and now head of the Peruvian Association of the Order. The investiture took place in the eighteenth-century Church of the Magdalena, and the Mass was offered by the Cardinal Archbishop of Lima, Juan Luis Cipriani.

Mass for Prince Pedro Luiz

The “week’s mind” Mass, or Mass of seven days, was held a week after the death of Dom Pedro Luiz of Orleans-Braganza in São Paulo, Brazil on June 8, 2009. The Mass was offered according to the extraordinary (or Tridentine) form of the Latin rite. The members of the Imperial Family of Brazil were in attendence. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories