Catholicism

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

First Gypsy Woman Martyr is Beatified

Emilia Fernández Rodríguez was killed during Spanish Civil War

The Catholic Church has beatified its first gypsy martyr in a ceremony in the Spanish city of Almería on the southern Mediterranean coast. Emilia Fernández Rodríguez, also known as “La canastera” (the basket-weaver), was one of 115 martyrs murdered in odium fidei by anti-Catholic militants during the Spanish Civil War.

The beatification ceremony took place in the city’s conference centre attended by over 5,000 people, including twenty-one bishops and four cardinals.

In 1938, Blessed Emilia Fernández was a poor gypsy woman living with her husband in Tíjola and surviving by basket weaving when the Republican forces occupied the town, shutting its church, and conscripting its menfolk. Emilia’s husband Juan with her help feigned blindness to escape conscription but was discovered and the couple were imprisoned separately.

Arriving at the women’s prison in Gachas-Colorás, Blessed Emilia was already pregnant and was jailed alongside many other practicing Catholic women who had refused to abjure their faith. Illiterate and never having been catechised despite being baptised, Blessed Emilia was taught how to pray the Rosary by another inmate. Her devotion to this Marian prayer and meditation attracted the ire of the prison authorities who threw her into solitary confinement for refusing to reveal which of her fellow inmates had catechised her.

After the birth of her baby girl, Ángeles, Blessed Emilia died as a result of her weakened condition from malnutrition and the appalling conditions of her isolation. Just twenty-three years old, her body was dumped into a common grave in Almería.

Challoner’s House

Challoner’s House — Rather humble for an episcopal palace, but such was the function of No. 44, Old Gloucester Street in Holborn during the time of Bishop Richard Challoner.

If it seems an odd spot for London’s Catholic bishop, it can be explained by its close proximity to the chapel of the Sardinian Embassy off Lincoln’s Inn Fields. At this time, of course, the Mass was still illegal and the only places Catholics in London could worship were the embassies of the Catholic nations. To protect the underground bishop, the house in Old Gloucester Street was actually rented in the name of his housekeeper, Mrs Mary Hanne.

After a perfect breakfast on Saturday morning the sun was shining so I decided the three-and-a-half miles home from St Pancras were best managed on foot. If architectural or historical curiosities are your fancy then foot is the way to travel, and so it was by pure chance that I stumbled upon No. 44. It seemed particularly appropriate that the night before a whole gang of us — Brits, Swedes, Italians, etc. — had been drinking in the Ship Tavern in Holborn where Bishop Challoner was known to offer the occasional clandestine Mass. (more…)

The Old Scots College

Via delle Quattro Fontane, Rome

Next month I’m off to Rome and the last time I was there I happened to walk past the old Scots College on the via delle Quattro Fontane. The Pontifical Scots College is probably the oldest Scottish institution abroad and certainly one of the most important, both historically and today. As Scotland’s primary seminary it has — almost literally — helped form the soul of the country, particularly during times of widespread persecution back in the mother country.

The church of Sant’Andrea degli Scozzesi (St Andrew of the Scots) was built in 1592 during the reign of Clement VIII, and early in the seventeenth century the church and neighbouring hospice were given over to the Scots College which had been founded a few years before. The seminary building itself was (I believe) built much later, in the nineteenth century after the college briefly ceased instruction due to the tumult of the French Revolution.

Sadly the building was not very well maintained and by 1960 it was falling apart. It was decided to sell the old college buildings in the Via delle Quattro Fontane and move to a larger site out the middle of nowhere in the Via Cassia. The move was made in 1964, and the Scots College has remained there ever since, while the old college housed a bank for many years and more recently a lawfirm.

1950s Ireland, the Church, and the Arts

Sitting in Dublin Airport waiting for a flight last week I picked up a copy of the Irish Arts Review which featured a number of interesting pieces (including something by our own Dr John Gilmartin).

Among the articles was an interview with the artist and printmaker Alice Hanratty (born 1939), a member of the Aosdána as well as of its governing council the Toscaireacht.

It was interviewer Brian McAvera’s question to Ms Hanratty about Ireland in the 40s and 50s and her response that proved most interesting.

BMcA: Artists, nevermind historians, often talk about the dark days of the 1940s and 1950s in Ireland: petty, parochial, restrictive, dominated by the Catholic Church, politically conservative and sexually repressed. How did you see this period and was it in any way formative for you as an artist?

AH: I have some experience of the period in question and don’t really recognise the description that you quote.

As far as the arts are concerned you must remember that important Irish poets, dramatists, and novelists, and also painters and sculptors worked at that time. Brian Fallon discusses all that in his An Age of Innocence. As for ‘politically conservative, restrictive, dominated by the Catholic Church’ these I think are quite sweeping statements by people who did not actually live at that time and are re-stating a received perception which is inaccurate.

As for domination by the Catholic Church, to some degree people allowed themselves to be dominated. They were OK with it. It suited them. It provided answers about the imponderables such as death. Nor should it ever be overlooked that the vicious war waged against the Irish people and the practice of their religion by way of the penal laws have had a huge detrimental effect on the national psyche which is not yet dispersed even in the 21st century.

As for political conservatism (don’t start me), that was established by the Free State Government in the 1920s making a deliberate and successful move to stamp out any form of socialism that might develop. Of course the Church was pleased to be of help there, but was not the instigator. President Higgins made reference to this period in one of his 1916 commemoration addresses, so anyone seeking enlightenment in these matters would find it there.

Were the 1940s and 1950s influential for me as an artist? No. I was too young and was not looking outwards for inspiration.

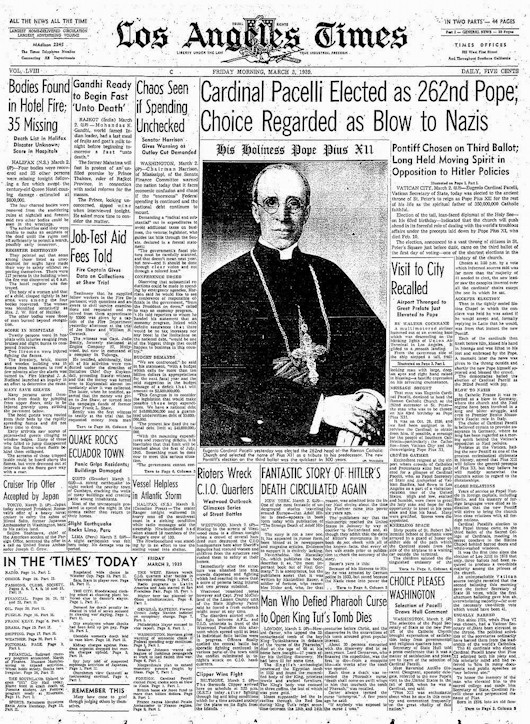

The L.A. Times on Papa Pacelli

How News of the Election of Pius XII was Received in 1939

The case against Pope Pius XII, accusing him of complicity in the crimes of Nazism, has been so thoroughly debunked — by Jews like Gary Krupp and Rabbi Dalin more than any — that it is no longer even worth refuting.

Still, it’s interesting to read the Los Angeles Times’s coverage of his election as Supreme Pontiff in the difficult year of 1939:

BLOW TO NAZIS

… The choice of Cardinal Pacelli is believed certain to provoke annoyance in Germany, where he long has been regarded as a moving spirit behind the Vatican’s opposition to Nazi policies.

As the news report goes on to note, Cardinal Pacelli was elected in only three ballots — the quickest papal election since that of Leo XIII in 1878.

The Ordination of a Priest

Michael Rennier and I first met some years ago as we moved in the same vaguely intellectual circles that congregated in various places between New York and Boston. He was an Anglican clergyman then, having been raised a Pentecostal Christian and endured a long sojourn in the Episcopal Church in which he was called to formal ministry. Michael disguises his intellectual rigour with a light heart and a good sense of humour, and I was deeply pleased to see that rigour guided him, his wife, and family into the Catholic Church in 2011. I believe he had been knocking on the doors of the Archdiocese of Boston asking to be brought in under the Pastoral Provision of John Paul II, but I imagine the last thing that Archdiocese wanted to take on was the cost of a man with a wife and kids to look after as a seminarian, then deacon, then priest.

Things moved along anyhow, and Michael moved his family back to his ancestral homeland in the Middle West – T.S. Eliot country – to find his way in life and see what the future would bring. Thanks be to God, last week, on the feast of the Immaculate Conception, Michael was ordained a priest of the Catholic Church at the Old Cathedral of Saint Louis in Missouri.

In a beautiful reflection, Michael recalls sitting in Yale’s Sterling Memorial Library as a Protestant clergyman-in-training:

I was reading the Apologia; the story of [John Henry Newman’s] conversion to the Catholic Church. I was particularly bothered by one specific bit. I was at the part where Newman makes his point that, fundamentally, there is no difference whatsoever between Arianism and Anglicanism. One is reviled and discredited, the other respectable and vital. But look closer, Newman argued, look underneath. What is there? Rebellion. There, buried beneath the sartorial splendor, the monarchy, the gorgeous liturgy, the incense, the polyphonic chant, and the prestige of Oxford… was a group of Christians steeped in the bitter throes of willfulness. […] Newman got to me that day, blinking in the fluorescent lights of a now disappeared world. My own world, comfortable as it had been, began to slip away as well.

After all, outward appearances are not always what they seem.

Further along, Michael relates attending Mass as a Protestant:

It was fascinating. I was attracted to it. I felt something solid about it, comforting, and yet, I knew for a fact that these people worshiped statues! Okay, with age my critique became a bit more subtle. But in the long run, aren’t all our arguments against the Church just as silly and vain? She outlasts us all. We can kick and scream and throw tantrums; legislate against her, slander her, outlaw her priests and persecute her children: the Church still prevails. She fears nothing. And because of this, she is able to be generous and patient.

The greatest novel of all time (no one argue with me on this) is Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh. In it, Waugh describes a family who keep their country seat at Brideshead in the ancestral home. The family itself is a mixed lot; A father living abroad in sin, a domineering mother, a son who is a flamboyant dandy, a worldly daughter, and an overly-childlike daughter. Waugh describes the slow decline of Brideshead as the family disintegrates and scatters. This dissipation works itself out universally in the advent of the Great War [sic], which finally swallows up all of England and turns Brideshead into quarters for Army command. In the end, though, we are left with a scene in the house’s private chapel, where the altar lamp is still lit and a lone priest says mass for an old woman. I am a lot like that family. Many of us probably are.

You see, conversion is a gift. Mother Mary holds her Son for us, patiently suffering at the foot of the Cross. We can ignore her, go our own way, rebel … it doesn’t matter. Hanging on the Cross, Christ says to each and every one of us “Behold your Mother.” She is here still. Waiting. We may be elsewhere, doing God knows what, but above the altar the candle still flickers. This is the light by which, in time, we find our way home.

His reflection is worth reading in full.

I hope readers will join me in getting a prayer of thanksgiving in for Fr Michael as well as for his wife and their five children. This is barely even the beginning.

Mendicant Architecture in Mediaeval Oxford

An interesting video from two American academics on the subject of Mendicant architecture in mediaeval Oxford, with some three-dimensional theoretical reconstructions of the Dominican and Franciscan houses in the city.

Both orders returned to Oxford in the twentieth century. The Capuchins refounded Greyfriars in 1910 and it was recognised as a permanent private hall (PPH) of the University in 1957. Its end as an academic institution was announced sadly on its fiftieth anniversary in 2007, but Greyfriars continues as a Capuchin friary.

Blackfriars under the Dominicans is still going strong, exercising a triple function as a priory of the Order of Preachers, a house of studies for the English province of the Order, and a PPH of the University of Oxford.

Church of St James, Spanish Place

Always interesting to see a building you know well from a perspective you’ve never seen before, as in this photo of the Church of St James, Spanish Place, taken from Manchester Mews. The church somehow seems more imposing — like a great rounded keep.

A few months ago I was corralled into some favour or other that required a bit of muscle to move this there and whatnot, the payoff of which was it afforded an opportunity to explore the triforium of this Marylebone church and see the interior of the building from an entirely new vantage point.

It also meant being able to view in better detail the beautiful stained glass windows — many of them the gift of various Spanish royals, given that this parish originates as the chapel of the Spanish embassy (hence its name).

Letter to the Editor

A letter to the editor printed in this week’s edition of The Tablet:

Brendan Walsh’s report (“Heythrop’s fate”, 17 September) of a senior academic suggesting that the demise of Heythrop was an episode in a long struggle between “outward-facing, inquisitive, challenging” theology on one side and “inward-looking, submissive, unquestioning” theology on the other is telling.

Positing such a simplistic binary split between Enlightened Me and Poor Ignorant You is patronising to those attempting to live out the radical beauty of the Christian life in tune with Catholic teaching. It’s not surprising that an institution with academics holding this view is entering its death spiral, while religious communities that don’t consider basic orthodox belief as optional are bursting at the seams.

Few things are more challenging – and more rewarding – than faithfulness; while some cling to clapped-out heterodoxies and managed decline, the rest of the Catholic world has moved on.

ANDREW CUSACK

London SW1

The Red Mass in Edinburgh

The opening of Scotland’s judicial year was marked this past Sunday by the Archbishop of St Andrews & Edinburgh offering the customary Red Mass in St Mary’s Cathedral.

This year Archbishop Leo Cushley was joined by Lord Drummond Young and his fellow Senators of the College of Justice, Lord Uist, Lord Doherty, Lord Matthews, and Lady Carmichael.

Gordon Jackson QC, the Dean of the Faculty of Advocates, and Austin Lafferty of the Law Society of Scotland joined many sheriffs, QCs, advocates, solicitors, trainee solictors, paralegals, and law students.

“These men and women serve the nation in a high office and come here to ask the Lord’s blessing upon this year’s work that they carry out on our behalf,” Archbishop Cushley noted in his homily.

“Know that we appreciate the difficult and complex tasks that you have and the duties that you perform – which are very onerous – on behalf of us all and that you be assured of our prayers and our support for all that you do to apply the law of the land with virtue and with justice and with mercy.”

The Flag of the Arab Revolt

An English Catholic contribution to Pan-Arabist vexillology

Though often overshadowed by the more theatrical T.E. Lawrence, Sir Mark Sykes (7th baronet) was still by all accounts a remarkable man. Educated by Jesuits in England, Monaco, and Belgium, young Sykes had instilled in him a cosmopolitan sense of adventure by travelling with his mother across the Middle East, Mesopotamia, India, and Asia throughout his childhood. It was during his travels in the provinces of the Ottoman empire that Sykes’s lifelong fascination with Islam began. By the time it was appropriate to go to university he found the atmosphere and formality of Cambridge stifling and left without taking a degree, but not without gaining a reputation for good humour with a special talent for mimicry.

At 25 Sykes wrote his first book, Dur-ul-Islam, which Kipling found so fascinating he couldn’t put it down until forced to by the necessity of sleep. After forays in the civil and diplomatic services, Sykes was elected to Parliament as the Unionist candidate in Kingston upon Hull. A romantic tory at heart, he disliked being labelled as conservative. “It is impossible to be a Conservative,” Sykes argued, “when there is nothing left to Conserve.”

At 25 Sykes wrote his first book, Dur-ul-Islam, which Kipling found so fascinating he couldn’t put it down until forced to by the necessity of sleep. After forays in the civil and diplomatic services, Sykes was elected to Parliament as the Unionist candidate in Kingston upon Hull. A romantic tory at heart, he disliked being labelled as conservative. “It is impossible to be a Conservative,” Sykes argued, “when there is nothing left to Conserve.”

When the Great War broke out in August 1914, Sykes recruited a batallion of men from his Yorkshire estates alone, but his unique insight into the Ottoman empire was put to good use in military intelligence. In May 1916 he was sent to negotiate the Anglo-Franco-Russian carving-up of Ottoman Asia with Charles Georges-Picot of the Quai d’Orsay.

The question of what the Turks’ Arab subjects themselves wanted only became a question the following month with the beginning of the Great Arab Revolt. This huge undertaking to wrest the Arab peoples from centuries of Turkish rule found a leader in the Sharif and Emir of Mecca, Hussein bin Ali of the Hashemite dynasty, but the uprising needed a symbol to rally round, and Sykes was the man for the job.

The flag of the Arab Revolt that Sir Mark Sykes designed was to be one of the most influential flags in the history of vexillology, launching the four pan-Arab colours into the world of flag design. Black represented the Abbasid dynasty, green for the Fatimids, and white for the Ummayad, all of which was united by a triangle of red for the Hashemites who hoped to rule Arabia.

Twelve modern states today employ designs descended from the flag Sykes designed. Among them is Jordan, now the only land ruled by the Hashemites – the Sauds kicked them out of Hejaz while the brutal slaughter of the 1958 coup deprived them of the Iraqi throne.

Jordan’s Red Sea port of Aqaba was made famous by its capture during the Great Arab Revolt – retold in David Lean’s 1962 film ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ – and it is there today that Sykes’s flag flies from one of the tallest flagpoles in the world.

Master Mitsui’s Ink Garden

Daniel Mitsui is one of the most interesting artists out there, exhibiting a wide range of influences from the Celtic to the Oriental. Among his latest works is an ink drawing on a Catholic theme. As Daniel explains:

I received a commission to create a Catholic religious drawing in a Chinese style. These explorations into artistic traditions outside of European Christendom are always exciting, and China was new territory for me. When developing the concept for the project, I looked to one of the early missionaries to China, the Italian Jesuit Matteo Ricci.

Some time in the very early 17th century, Ricci gifted four European prints to the Chinese publisher Cheng Dayue: two engravings by Anthony Wierix from a series illustrating the Passion and Resurrection of Christ, another by the same artist reproducing the painting of the Virgin of Antigua in Seville Cathedral, and one by Crispin De Pas the Elder from a series illustrating the life of Lot.

Master Cheng copied these images into his Ink Garden, a model book of illustrations and calligraphy. The missionary saw this as a good opportunity to disseminate lessons in Christian doctrine and morality among the Chinese population.

Continue reading here.

Joy

Something I constantly notice is that unembarrassed joy has become rarer. Joy today is increasingly saddled with moral and ideological burdens, so to speak. When someone rejoices, he is afraid of offending against solidarity with the many people who suffer. I don’t have any right to rejoice, people think, in a world where there is so much misery, so much injustice.

I can understand that. There is a moral attitude at work here. But this attitude is nonetheless wrong. The loss of joy does not make the world better — and, conversely, refusing joy for the sake of suffering does not help those who suffer. The contrary is true. The world needs people who discover the good, who rejoice in it and thereby derive the impetus and courage to do good. Joy, then, does not break with solidarity. When it is the right kind of joy, when it is not egotistic, when it comes from the perception of the good, then it wants to communicate itself, and it gets passed on. In this connection, it always strikes me that in the poor neighborhoods of, say, South America, one sees many more laughing happy people than among us. Obviously, despite all their misery, they still have the perception of the good to which they cling and in which they can find encouragement and strength.

In this sense we have a new need for that primordial trust which ultimately only faith can give. That the world is basically good, that God is there and is good. That it is good to live and to be a human being. This results, then, in the courage to rejoice, which in turn becomes commitment to making sure that other people, too, can rejoice and receive good news.

Lourdes: To Be a Pilgrim

As today is the feast of Our Lady of Lourdes — and consequently the World Day of the Sick — here is the documentary we made regarding the Order of Malta’s annual pilgrimage to Lourdes each May.

Friday 8 January 2016

– Ross Douthat’s sensitive and thoughtful commentary on the state of the Catholic church (in the New York Times, of all places) has previously sparked apoplexy on the part of liberals, hilariously inspiring a host of bien-pensant establishment lefties to point out he has “no professional qualifications for writing on the subject”.

In a recent blog post, Douthat points out how difficult it is to engage in dialogue with lefty Catholic thinking given that it often assumes we can reinterpret anything whenever we want while ignoring centuries of fervent intellectual inquiry and church teaching. For these liberals, it is always Catholicism: Year Zero.

– The British writer Tibor Fischer is no conservative, but he’s often written how ridiculous it is for people to claim the Viktor Orbán is a dictator, whether in the Guardian or in Standpoint. (I myself had to take to the pages of the Irish Times to defend the Hungarian PM.)

Now Fischer writes in the Telegraph asserting that Viktor Orbán is no fascist: he’s David Cameron’s best chance at reforming the European Union.

– Still in Hungary, the British Embassy in Budapest is moving out of its home of nearly seventy years and into the recently vacated Dutch embassy.

– Everyone loves the leader of the Scottish Conservatives, Alex Massie says. But still no one will vote for her.

– Agnostic Southern Episcopalian chain-smoking monarchist with a penchant for misanthropy: Florence King, RIP.

– Speaking of misanthropy, is Groucho Marx’s humour nihilist? Shon Arieh-Lerer thinks Lee Siegel’s book might be overthinking things a bit.

– And finally, the United Nations Library in New York has announced which of its books was checked out the most often in 2015: Immunity of heads of state and state officials for international crimes.

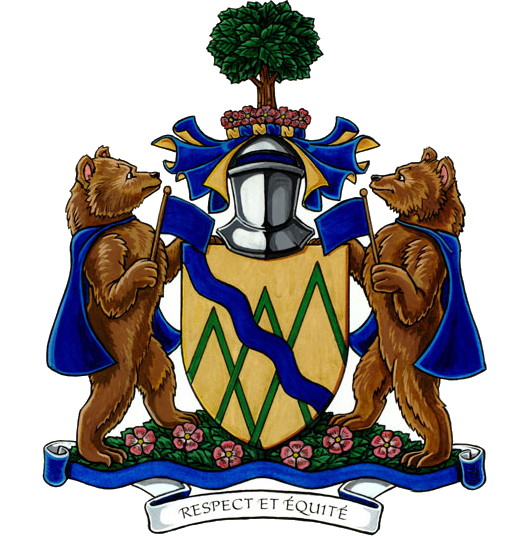

Caped Bear Cubs in Canadian Arms

As my sister was educated (or something to that effect) by Ursulines, a recent addition to Canada’s Public Register of Arms, Flags, and Badges caught my attention. The Queen of Canada granted a coat of arms to the Quebec municipality of Sainte-Angèle-de-Mérici in 2013 (pictured above).

The shield of the arms features three chevronels represent the mountains surrounding the area while their number reminds us that Sainte-Angèle-de-Mérici is a municipality formed from two townships — Cabot and Fleuriault — and the single seigneury of Lepage-et-Thivierge. The wavy blue stripe represents the Mitis River, while gold symbolises the agricultural industry of the Sainte-Angèle-de-Mérici.

The charming aspect are the supporters: two bear cubs. St Angela Merici was the founder of the Ursulines — the Order of St Ursula — and ‘Ursula’ is Latin for ‘little female bear’.

“The bear also symbolizes bravery, thus signifying St. Angela Merici’s martyrdom,” the Canadian Heraldic Authority further explains. “The cloak is one of her traditional attributes. The flags (drapeau in French) honour Angèle Drapeau (1799-1876), the youngest daughter of Seigneur Joseph Drapeau and benefactor of the municipality.”

Chartres 2015

Chartres is filed in my mind as the cathedral of my childhood. I must’ve been around 4 or 5 when I first walked amidst this medieval vision of stone and stained glass — some years before I ever visited the cathedral of New York where I was born. Cathedrals offer a prodigious mental stomping ground for the imagination of a young boy, and David Macaulay’s pen-and-ink book Cathedral (winner of the 1975 Deutscher Jugendliteraturpreis — take note!) I read and re-read over and over again as a child.

The marvel of this great church is that, while most medieval cathedrals took centuries to build, Chartres was constructed in an astonishing fifty-four years between 1194 and 1250, lending it a unity as an architectural composition that puts its rivals to shame. Chartres was made a diocese as early as the third century and tradition even upholds that from around the year 50 B.C., local Druids who had heard the prophecies of Isaiah here enshrined a statue of the ‘Virgo Paritura’, the Virgin-who-will-give-birth.

Having such a long history, Chartres’ fortunes have waxed and waned. In medieval times it was one of the most popular pilgrimage shrines in all of Europe, and in the 11th and 12th century its cathedral school far outshone England’s provincial attempt at a university at Oxford. But France’s civil wars and then revolution put an end to the town’s days as a destination for pilgrims until the poet Charles Péguy revived them himself in the years leading up to the First World War.

For the past thirty-three years, the largest pilgrimage to Chartres has been undertaken over Pentecost weekend, a bank holiday in France which happily coincided with our second May bank holiday in Great Britain this year. On this trek, over 11,000 pilgrims walk all the way from Notre Dame de Paris to Notre Dame de Chartres. Our chapter of about twenty pilgrims marched under the banner of Notre Dame de Philerme, patroness of the Order of Malta — mostly French and British but with a few participants from other countries as well. (more…)

Change in the air at the Catholic Herald

Title will cease to operate as a newspaper and relaunch in magazine format

Britain’s leading Catholic publication, the Catholic Herald, will be relaunching as a magazine before the end of this year. Invites have already gone out to an event celebrating the change to be held in early December.

The relaunch might be interpreted as a move against the Tablet, which styles itself “the international Catholic weekly” and has been nicknamed “The Bitter Pill” by English Catholics for its widely perceived lack of faithfulness to Catholic teaching. The Tablet is associated with the country’s old liberal Catholic elite, counting among its trustees such figures as Chris Patten and Sir Gus O’Donnell. A Herald reader, meanwhile, is more likely to be young, intellectual, and strongly influenced by John Paul II and Benedict XVI.

When told of the news, one young churchman welcomed the change as a good move for the generally orthodox Herald against its looser rival. (more…)

L’Osservatore Romano goes Hungarian

Magyarophiles will be pleased to learn that L’Osservatore Romano, the Vatican newspaper, will begin appearing in Hungarian. The new edition will appear every other week as a four-page insert into Új Ember, the Hungarian Catholic weekly founded in 1945. “We are a small editorial staff,” Balázs Rátkai, editor-in-chief of the weekly, told L’Osservatore.

“However, our intention is to probe and to make our readers think. The collaboration with the Vatican daily is of historic importance for the life of the weekly and of the entire local Church; it not only brings the Universal Church and the Pope closer to us; it will also enrich readers, and through them all of Hungarian society, with new thoughts, opinions and answers.”

Printed as a daily broadsheet in Italian, the Vatican newspaper also has weekly tabloid editions in French, Spanish, English, German, and Portuguese, as well as a monthly version in Polish.

Saturday: Day of Fasting & Prayer for Peace in Syria

Given the urgent situation, please see the following from the Fathers of the London (Brompton) Oratory:

Day of Fasting and Prayer for Peace in Syria

This is in response to the following call to fasting and penance issued by His Holiness Pope Francis:

“On 7 September, in Saint Peter’s Square, here, from 19:00 until 24:00, we will gather in prayer and in a spirit of penance, invoking God’s great gift of peace upon the beloved nation of Syria and upon each situation of conflict and violence around the world. Humanity needs to see these gestures of peace and to hear words of hope and peace! I ask all the local churches, in addition to fasting, that they gather to pray for this intention.”

The London Oratory invites you to join the Holy Father in prayer for this urgent intention.

6.45pm-11.00pm Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament, the Little Oratory

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories