Art

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

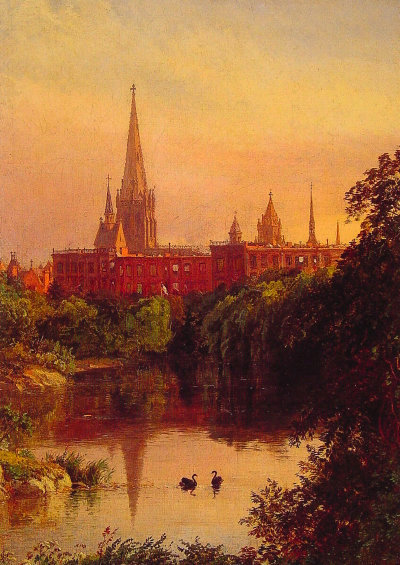

Stoddart’s Ode to Ossian

The Queen’s Sculptor Plans Great Literary Monument in the West of Scotland

Word reaches me that Alexander Stoddart, the Queen’s Sculptor in Ordinary for Scotland, has dreamed up a massive monument to Ossian. “For fifteen years Stoddart has planned ‘a national Ossianic monument’ on the west coast of Scotland,” writes Ian Jack in The Guardian. “The scale is immense. Stoddart wants a great amphitheatre cut into the rock with Ossian’s dead son, Oscar, also cut from rock, prone on his shield on the amphitheatre’s floor.” The project would be the biggest literary monument in the world, surpassing the Scott Monument on Princes Street in Edinburgh. It could be the project of a lifetime for Stoddart.

“He says a lot of people are keen, including Scottish government ministers, landowners and historians, and that a site has been identified in Morvern and a preliminary survey completed by the engineers Ove Arup. There is also environmental opposition: the kind of people, according to Stoddart, who will ‘always find two mating ptarmigan no matter where we choose’ and haven’t taken into account Schopenhauer’s view that ‘the sound of nature is the sound of perpetual screaming’. It may account for the two death threats he says he has received.”

“The Ossian poems, especially ‘Fingal’, took Europe by storm,” the journalist continues, “and gave it a new notion of the savage and sublime. A cave on Staffa became ‘Fingal’s Cave’. Goethe incorporated Ossian into The Sorrows of Young Werther and Schubert used passages of Goethe’s translation in his lieder. By Stoddart’s estimate, nothing, not even the work of Burns, has made a larger Scottish contribution to European culture. Ossian established the Scottish wilderness as a destination for Europe’s earliest tourists. Also, by ennobling Celtic antiquity, it changed Scotland’s sense of itself.”

The traditional style of Alexander Stoddart, an avowed neo-classicist, has provoked foaming at the mouth in the rather dull arts establishment, but his works — such as the David Hume statue on the Royal Mile and the frieze on the Sackler Library at Oxford — have proven popular. Scotland’s greatest living sculptor has completed a bust of Scotland’s greatest living composer, James Macmillan, as well as of Britain’s greatest living philosopher Roger Scruton. (The old-school lefty Tony Benn — another living national institution — is the subject of a Stoddard bust as well).

“The paradox is that, by revering and understanding abandoned traditions, [Stoddart] has emerged as one of the most original artists in Britain: a stranger to his times.”

Early Morning, Madison Square

Charles Courtney Curran, Early Morning, Madison Square

Oil on canvas, 22 in. x 18 in.

1900, National Arts Club, New York

In the Dublin auction houses

THOUGH THE BORING brains of tawdry metropolitan Londoners are all too quick at relegating Dublin to the provincial periphery of the mind, the Irish capital is a perpetual treasure trove for the old-fashioned and right-minded. A number of items of interests have recently been sold at the auction houses of the fair city, including two ceremonial uniforms (above) of that famous Dubliner, Sir Edward Carson QC. Carson was the lawyer and statesmen who passionately, but without bigotry, opposed the cause of Irish home rule. He was the defending barrister in the Archer-Shee case and led the Marquess of Queensberry’s team in Oscar Wilde’s doomed libel action. Carson and Wilde had been at Trinity together (where — little known fact! — Carson was a keen hurler), and the famous wit quipped of Carson “I trust he will conduct his cross-examination with all the added bitterness of an old friend.”

Having a fine mind for the law and being politically active meant that Carson moved through several layers of British government, holding numerous offices and positions. He was a Privy Counsellor twice over (of both Ireland and the United Kingdom), a Queen’s Counsel, served in the House of Commons as leader of the Irish Unionists, and held portfolios in the British Cabinet. The two ceremonial uniforms auctioned at Whyte’s of Molesworth Street are from his appointment as Solicitor General for England & Wales in 1900. (He had been Solicitor-General for Ireland in 1892, and was later Attorney General for England & Wales, in which position he was succeeded by the F.E. Smith of Chesterton’s famous poem).

The two black wool morning coats feature gold bullion trimming and buttons, and are sold with a pair of trousers with gold filigree stripe matching the lesser uniform, and knee breeches & silk stockings for the greater uniform. The vellum appointment as Solicitor General was also included, in a red leather box with a gilt impression of the royal arms. Whyte’s estimated a sale of €50,000-€70,000, but the lot’s realised price was €42,000. (more…)

A Message from the Minister of Culture

I’ve sometimes thought that the Director of the Metropolitan Museum is New York’s unofficial Minister of Culture. Concerned New Yorkers were at the edge of their seats with anticipation to discover who would be chosen to direct this great museum once it was announced that the legendary Philippe de Montebello was relinquishing the throne. As The New Criterion put it “Few events have been awaited with more trepidation in the world of culture — we were going to say ‘the art world,’ but it embraces much more than that — than the appointment of the next director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.”

The massive sigh of relief when Thomas Campbell was announced as the successor could probably be heard as far as the Louvre (or even the Hermitage), even though Campbell’s name was on none of the supposed shortlists for the job. Judging by his past as curator of tapestries, Campbell is widely believed to be utterly reliable at continuing the high standard maintained during de Montebello’s reign. May God guide him well in his task! (more…)

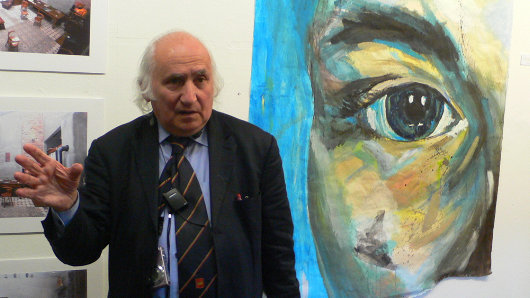

Richard Demarco

“We didn’t know quite how to take this, but we sat there entranced.”

ONE OF THE markedly few deficiencies of the English language is coming up with a word to describe Richard Demarco. The Scottish press have generally settled upon “impresario” but even that somewhat-ambiguous word fails to do the man justice. Ricky was born in Edinburgh in 1930, grew up in Portobello, and remembers the day when his mother held him back from school because Italy — from whence he stock came — had just declared war on Great Britain. He’s attended every Edinburgh Festival since the very first one began in 1947 — as the founders put it, to “provide a platform for the flowering of the human spirit” in the grim aftermath of the Second World War.

Richard Demarco, couchant, with noted Scots caricaturist Emilio Coia.

Richard Demarco, couchant, with noted Scots caricaturist Emilio Coia.In 1963, he cofounded the Traverse Theatre, Scotland’s theatre for new writing, and three years after that founded the Richard Demarco Gallery which promoted Scotland’s cultural interchange with artists across Europe including — very importantly to Richard — from behind the Iron Curtain that divided the continent into free and captive halves. This was during an age when many in the arts world were too busy sympathizing with the murderous totalitarianism that had subjugated half of Europe. Richard has been a deep critic of the choices made by the British government as patron of the arts throughout the decades of his life, but not too long ago he finally patched things up with the Scottish Arts Council.

Readers of Alexander McCall Smith’s 44 Scotland Street might recall the man who comes to speak to the Scottish Police College. The “really important person from the art world in Edinburgh”, as Mr. McCall Smith puts it, comes and tells the trainee constables about the gorgeousness of Italian carabinieri uniforms and how the Scottish psyche still suffers from the iconoclasm of the Reformation, and even suggests architectural alterations and more sympathetic decoration of the Police College. “We didn’t know quite how to take this, but we sat there entranced,” the character admits in 44 Scotland Street. Anyone who either knows Ricky or has been to one of his lectures would immediately recognize the unnamed subject of the passage.

I first met the man when I was a first-year student at St Andrews and he had come up from the capital to give a lecture. I can’t remember what the stated subject was but this is entirely irrelevant as so vast and wide-ranging is the mind & experience of Richard Demarco that he is known for (some would say “notorious for”) never keeping within the bounds of the stated subject. Those who invite Richard to speak shouldn’t bother with a subject, just make posters stating “RICHARD DEMARCO SPEAKS”, giving the date, time, and place, and a crowd of interested characters is bound to turn up. (more…)

Diary

I have been spending the past few days in a flat at the corner of Holland Park Avenue and Portland Road, in this verdant corner of the capital. The flat is clean, capacious, and handsome, but terribly modern. Indeed, it is so modern that it will soon be old; it will not exhibit the old age of the time-honoured and true, but rather the tawdry oldness of what had only recently been new. Pedantic students of interior design will study photos of it and discern “2008 I’d say… no! 2009!” But for now, it is still new, still fresh, and so, like a tomato fresh for the plucking, we will enjoy it while its moment is precisely appropriate.

Until now, I hadn’t much knowledge of this part of London, but find it a happy place to be in August. The weather has been mild and kind, and I spent part of the afternoon reading de Maistre — the St. Petersburg Dialogues — in the formal garden in Holland Park. The avenue itself is tree-lined, or rather tree-engulfed, such is the plentiful shade, and has a small selection of cafés: the Paul boulangerie which is becoming omnipresent, and the Valerie patisserie, both chains. Cyrano, at No. 108 Holland Park Avenue, is much preferred, and I decamped there for a light breakfast with a copy of the Scotsman from the local newsstand (the one on Ladbroke Grove, rather than the smaller one by the tube stop) while avoiding the miserable Irish cleaning lady who returns the modern flat to its pristine whiteness every Thursday morning.

Then to the Royal Academy, for the Waterhouse show. What an interesting artist! His earlier works so precise in detail and, for lack of a better word, academic. Yet in his later pieces, you can find a certain willingness to obfuscate, perhaps an admission that reality is not quite so precise and that the most accurate portrayal of reality requires a few lines to be blurred. Faces, and indeed all forms, remain clear throughout, but the architectural coldness of the earlier works on display gradually evolves to a more fluid depiction of Greek mythos and Keatsian tales. Waterhouse can vary in his details from the almost photographic to verging on impressionism in a single painting. Was that his intention? It was certainly the result.

My viewing companion — an old university friend — and I agreed that throughout all the themes portrayed by the artist one can’t help but feel an overwhelming Victorian-ness. Is this ex post facto because we know Waterhouse to be an High Victorian artist, or is there actually some inherent quality in the works that calls to mind that era? Very difficult to say, but those in London should not miss this exhibition of a popular yet under-appreciated artist — the Jack Vettriano of his day.

Who is in London in August anyhow? The text messages sent out, and their replies promptly received. “I’m in Geneva! Will be in Luxembourg next week if you’re on the continent.” I am not and will not be on the continent. “I have been unexpectedly called to Africa.” Well I’ve just come from there, though not the Sudan thank God. “You’re welcome to come to Gozo between the 5th and 15th for a pleasant, quiet holiday.” I will have returned to New York by then, alas. “Am up north in Lancashire; you’re welcome to come and visit, sample our recusant history!” Just haven’t got the time, alas.

But while many have escaped for the month, many yet remain. An afternoon drink at Rafe’s, with Fr. Rupert and Alex Williams. The Carlton is being refitted, so it was drinks at the East India Club instead with another university friend, during which we concur that office jobs are the absolute pits and we should have studied agriculture with the country girls at Cirencester rather than getting tawdry MAs in Scotland. There is no greater affirmation of the consequences of original sin than the omnipresence of the 9-to-5 office job.

Astute observers of this little corner of the web (if indeed we can use the plural for such a subset of the earth’s population) will recall an incident over two years ago now in which a certain Jack Russell terrier became rather more involved with my lower leg than I had envisioned was ideal. The dog, which goes by the name of Cicio Stinkiman, had noticed me playing with the only seeing-eye-dog in Scotland that knows how to genuflect and resented the attention I was paying to the bitch, to whom he obviously professed some attachment, ran up, and bit me in the calf.

You can imagine my surprise when I learnt that the beast in question is actually now not only living in London but actually residing in the Oratory. Indeed I saw the beast from a distance while waiting on Brompton Road for the Friday evening mass last week. His owner graduated from university (in Scotland, like all the wisest people) two years ago now but his mother banned poor Cicio Stinkiman from the German palace he might otherwise call home, perhaps informed along the voluptuous grapevines of Europe of the horrendous incident in which the beast had taken an unwelcome interest in my lower leg.

I am being far too unfair to poor Cicio, for he did apologise, and looked up at me with terribly apologetic eyes. Admittedly, that might’ve been because his master stood nearby holding a rolled-up copy of the Catholic Herald most threateningly. Still, pity the poor ignorant beasts. They have no conscience, and thus no real malice. Only we humans, with the freedom we abuse so easily, can claim that dubious achievement.

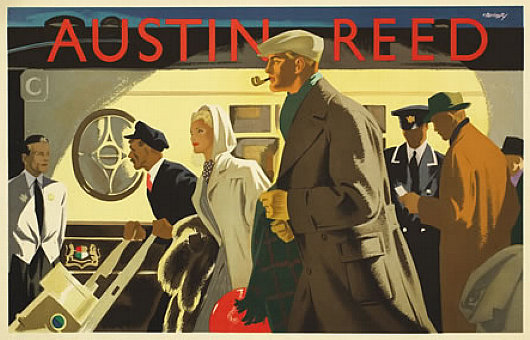

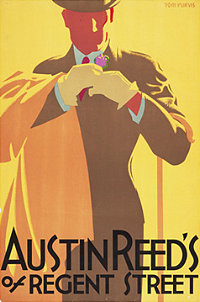

Austin Reed

The London mens’ clothier Austin Reed was founded in 1900 and set up shop in Regent Street in 1926 as the first men’s department store. The clothes were aimed at the upper middle class male, and the firm commissioned some of the best illustrator-designers of the day to promote its brand. The above poster, “Wagon-Lits”, is by a designer named Bomarry, about whom I can find absolutely nothing — surprising in this Age of Google.

The London mens’ clothier Austin Reed was founded in 1900 and set up shop in Regent Street in 1926 as the first men’s department store. The clothes were aimed at the upper middle class male, and the firm commissioned some of the best illustrator-designers of the day to promote its brand. The above poster, “Wagon-Lits”, is by a designer named Bomarry, about whom I can find absolutely nothing — surprising in this Age of Google.

The remaining posters presented here are from the Bristol-born Tom Purvis, one of the finest commercial artists of the twentieth century. Purvis came from an artistic family, being the son of the sailor & nautical artist T. G. Purvis. Much of his output was work for LNER — the London & North Eastern Railway — producing posters advertising the various attractions to be found along the LNER’s routes from London to Edinburgh (via York & Newcastle) and on to Aberdeen and Inverness; the railway also had an extensive coverage of East Anglia. In 1936 he was among the first to be given the title of Royal Designer for Industry, but he gave up poster design after the Second World War to concentrate on portraits and religious themes. (more…)

Cropsey in the City

Jasper Francis Cropsey, A View in Central Park — The Spire of Dr. Hall’s Church in the Distance

Oil on canvas, 17⅛ in. x 12⅛ in.

1880, Private collection

THE HUDSON RIVER SCHOOL artist Jasper Francis Cropsey has obtained of late an almost cult-like following, the kool-aid being distributed from the well-oiled machinery of the Newington-Cropsey Foundation in Hastings-on-Hudson, New York. Whether the object of worship is worthy of the faithful’s adulation is a matter of some speculation, but it’s admittedly refreshing to see a fan base surrounding a painter of the old school rather than one of the numerous gimmicky hacks floating around the New York art scene these days. Cropsey (like most Hudson River painters) is known for his luscious landscapes, so I thought it markedly unusual when I stumbled upon this painting, a cityscape. The artist’s vantage point is from The Pond in Central Park, looking over Fifty-ninth Street (Central Park South) towards where the old Plaza Hotel now stands. (more…)

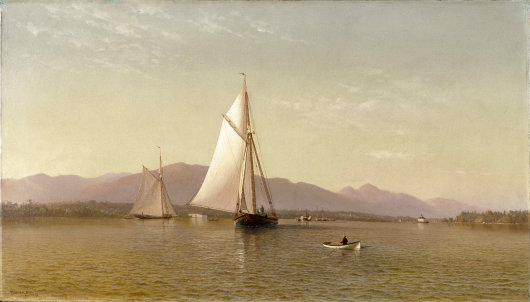

The Tappan Zee in the Age of Rig & Sail

Julian Oliver Davidson, The Hudson River from the Tappan Zee

Oil on canvas, (size not on record)

1871, Private collection

Francis Augustus Silva, On the Hudson near Tappan Zee

Oil on canvas, 20 in. x 36 in.

1880, Private collection

Francis Augustus Silva, The Hudson at the Tappan Zee

Oil on canvas, 24 in. x 42 3/16 in.

1876, Brooklyn Museum

Allies Day, May 1917

Childe Hassam, Allies Day, May 1917

Oil on canvas, 36½ in. x 30¼ in.

1917, National Gallery of Art (U.S.)

This has long been one of my favourite paintings, ever since I first saw it one day when I was very young while it was on loan to the Metropolitan. On a May day in 1917, Fifth Avenue was temporarily proclaimed “the Avenue of the Allies” and the British and French commissioners paraded down the boulevard with great ceremony. Childe Hassam set his easel on a balcony on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 52nd Street and took in the splendid scene towards the Church of St. Thomas and the University Club. Patriotic displays were much more lively then, involving bursts of flags and banners, than the rather dull and monotonous display of the single Stars-and-Stripes that became widespread after the World Trade Center attacks.

Interestingly, “Avenue of the Allies” aside, the United States was not actually allied to France and Great Britain during the First World War. President Wilson thought the United States was not so lowly as to merely intervene in a biased manner on the side of those it had lent money, but rather for the high-minded goal of establishing justice (or, as we might honestly call it, the destruction of Catholic Europe). The U.S., then, was merely a “co-belligerent” rather than an “ally”, though obviously this high-minded euphemism was lost on most people. During the Second World War, Finland found itself invaded by the Soviet Union and abandoned by the West, so — having no taste for Hitler and his Nazi charades — they became “co-belligerents” with Germany, rather than concluding a more distasteful alliance.

Hassam, who died in 1935, had little time for the avant-garde schools of art that came after the Impressionism he practised, and described modernist painters, critics, and art dealers as a cabal of “art boobys”. He was almost forgotten in the decades after his death, but the rising tide of interest in Impressionism from the 1970s onwards lifted even the boats of American Impressionists, and his Flags series of paintings are widely-known and much-loved today.

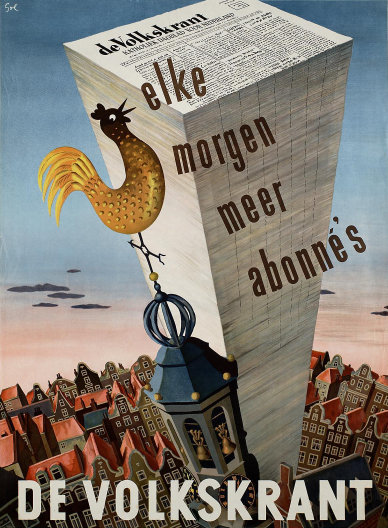

De Volkskrant

A FAVOURITE POSTER of mine combines a number of the things I love: newspapers, architecture, and the Netherlands. Arthur Goldsteen designed this handsome poster to advertise the daily newspaper De Volkskrant in 1950.

Paris Arts & American Arms

Maj. T. L. Johnson’s Cartographic Mural on Governors Island

One of the best aspects of the inter-war construction of Governors Island is that the refinement of McKim Mead & White’s architecture is matched inside by a series of interior murals painted under the auspices of the WPA. These murals often veered towards the refreshingly jocular, as can be seen in the War of 1812 mural in Pershing Hall (a corner of which is captured here by photographer Andrew Moore). The mural by Major Tom Loftin Johnson (educated at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris) depicted here, however, is a map of the area under the purview of the Second Corps, U.S. Army headquartered at Governors Island; namely the states of New York, New Jersey, and Delaware, and the then-territory of Puerto Rico.

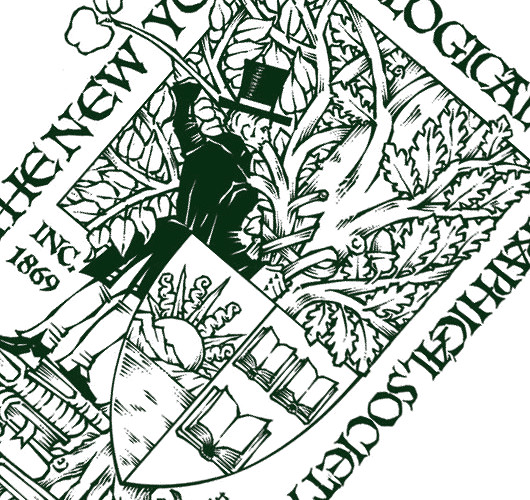

A new bookplate for the NYG&B

Fr. Guy Selvester reports on his resurrected Shouts in the Piazza blog that the great Marco Foppoli has designed a new bookplate for the New York Genealogical & Biographical Society. Mr. Foppoli is the most highly-regarded heraldic artist of our day, and the influence of the style of his mentor, the late Archbishop Bruno Heim, is apparent in his work.

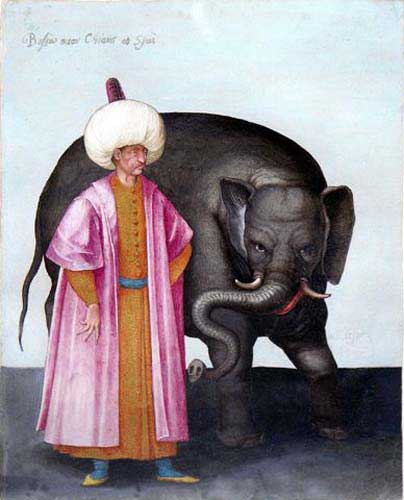

A Turbaned Pasha with an Elephant

Tempera and shell gold on paper, 10.0 in. x 8.8 in.

c. 1580-1585, Private collection (now for sale)

While known as a painter of large-scale works, a draftsman, and a printmaker, Jacopo Ligozzi — the court painter to the Grand Dukes Francesco I, Ferdinando I, Cosimo II, and Ferdinando II — also completed a series of drawings depicting Turkish traditional dress and costume. Interest in the Ottoman empire and its people increased after the great victory over the Turks at Lepanto in 1571, commemorated as a Christian feast to this day. Ligozzi never visited the Turkish realm himself but derived his inspiration for this particular illustration from the drawings accompanying the Venetian edition of Nicolas de Nicolay’s chronicle of the 1551 embassy of Henri II to the court of Suleyman the Magnificent.

That, at any rate, is the source of the Pasha; the inspiration for the elephant (of the African variety) remains undetermined. Suleyman gave an African elephant accompanied by a turbaned mahout and a staff of thirty to the future Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II, and it’s probable that Ligozzi used a printed depiction of this as a source for the picture here. (Earlier, in 1514, the King of Portugal gave an elephant named Hanno to Pope Leo X, a Medici).

This charming work, available from the Arader gallery of New York, is one from the series of tempera depictions of Turkish costume by Ligozzi, twenty of which are in the Uffizi, one in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and another in the Getty Museum of Los Angeles. It was probably painted between 1580 and 1585 while the artist was in the service of Grand Duke Francesco I de Medici. Ligozzi’s depictions were first bound in a single volume in the possession of the Gaddi family before, in 1740, the manuscript reached the hands of the Manifattura Ginori de Doccia, the porcelain factory founded outside Florence in 1735 by Marchese Carlo Ginori. There, it inspired a number of porcelain platters which are today dispersed around collections worldwide. The principal group of these illustrations were donated to the Uffizi in 1867.

Russia’s Treasures on the Banks of the Amstel

Seventeenth-century Amsterdam building will, from June, be home to collections from St. Petersburg’s Imperial Hermitage Museum

A new 100,000-square-foot space displaying works from the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg will open in Amsterdam this June. The Hermitage Amsterdam will be located in the Amstelhof, a former home for the elderly built in 1683 by the Dutch Reformed Church and transformed into a modern exhibition space by Hans van Heeswijk Architects. The opening exhibition, “At the Russian Court” — a “a deeply researched exploration of the opulent material culture, elaborate social hierarchy and richly layered traditions of the Tsarist court at its height in the nineteenth century” — will display 1,800 works from the massive collection in St. Petersburg and continue until the end of January 2010.

First Troop, Philadelphia City Cavalry

Watercolor, gouache, and graphite on white laid paper, 9 in. x 7 1/4 in.

c. 1811-1813, Rogers Fund

Previously: The Prince of Wales in Philadelphia

Some Afrikaners

“In my father’s shop,” writes the photographer David Goldblatt, “serving Afrikaners, I found, almost in spite of myself, that I liked many of them and, to my surprise, that I was beginning to enjoy the language. There was a warm straightforwardness and an earthiness in many of these people that was richly and idiomatically expressed in their speech. And, although I have never advanced beyond being able to speak a sort of kombuistaal, I delighted in our conversations. Yet, withal, I was very aware that not only were most of these people Nationalists, strong supporters of the Party and its policies, but that many were racist in their very blood. Although anti-Semitism was now seldom overt, they made no secret of their attitude to blacks, who at best were children in need of guidance and correction, at worst sub-human. I was much troubled by the contradictory feelings of liking, revulsion, and fear that these Afrikaner encounters aroused in me and felt the need somehow to come closer to these lives and to probe their meaning for me. I wanted to do this with the camera.

“I had begun to use the camera long before this in a socially conscious way. And so I began to explore working-class Afrikaner life in our district. I drove out to the kleinhoewes around the town. I would stop and ask people if I might do some portraits of them or spend time with them while they went about whatever they were doing. In this way I became intimate with some of the qualities of everyday Afrikaner life in these places, and with some of its deeply embedded contradictions.

“An old man sits for me. A black child comes and stands next to him, looking at me with curiosity. The man turns and says to the child, ‘Ja, wat maak jy hier, jou swart vuilgoed?‘ (Yes, what are you doing here, you black rubbish?), the insult meant and yet said with affection. How is this possible? I don’t know. But the contradiction was eloquent of much that I found in the relationship between rural and working-class Afrikaners and blacks: an often comfortable, affectionate, even physical intimacy seldom seen in the ‘liberal’ circles in which I moved, and yet, simultaneously, a deep contempt and fear of blacks. …

“Travelling through vast, sparsely populated parts of the country with my camera became a major part of my life at that time. I think that our landscape is an essential ingredient in any attempt at understanding not just the Afrikaner but all of us here. We have shaped the land and the land has shaped us. Often the land was unforgivingly harsh. Yet, the harsher the landscape the stronger the Afrikaners’ sense of belonging seemed to be. Many of the people whom I met in the course of those trips had a rootedness in the land of which I was very envious. Envious in the sense that I couldn’t claim 300 years of ancestry in this country. Yet, increasingly, I felt viscerally bonded to it.”

The Bad Shepherd

Pieter Brueghel II, The Bad Shepherd

Oil on panel, 29 in. x 41¼ in.

c. 1616, Private collection

With an original estimate of £1,000,000–£1,500,000, Pieter Brueghel the Younger’s The Bad Shepherd sold at a final hammer price of £2,505,250 at Christie’s in London this July. As the house lot notes state, it is “one of the most original and visually arresting of all images within the Brueghelian corpus of paintings”.

I am the good shepherd. The good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep. He who is a hireling and not a shepherd, whose own the sheep are not, sees the wolf coming and leaves the sheep and flees; and the wolf snatches them and scatters them. He flees because he is a hireling and cares nothing for the sheep.

It is significant that the distant horizon behind the sheep is broken only by a solitary church spire and a small farmstead. They seem to suggest that in abandoning his responsiblities the shepherd also rejects both the church and the community as he rushes headlong in the opposite direction. The mental anguish experienced by the shepherd is mirrored in a remarkable way by the barren landscape, shown from a dizzying bird’s eye perspective, stretching back into infinity. Interwoven only by vein-like tracks and ditches that lead the eye into the distance, the landscape is one of the artist’s most extraordinary achievements and very much a precursor to the psychological landscapes of the 20th century.

There is something arrestingly modern about this painting that fascinates me.

A Tribute to Cockerell

Carl Laubin, A Tribute to Charles Robert Cockerell, RA

Oil on canvas, 39′ 11″ x 60′

2005, Private collection

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories