Art

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Marlow’s St Paul’s Capriccio

c. 1795; oil on canvas, 60 x 41 in.; London, Tate Gallery

The view of St Paul’s Cathedral as if it had been completed according to the original plans of Wren and with Hawksmoor’s baptistry (which I posted yesterday) reminded me of this capriccio by William Marlow. And then this in turn recalled my 2005 post If London Were Like Venice.

Carl Laubin’s Architectural Fantasies

While the subjects of his works are varied, Carl Laubin has become best known for his architectural paintings. Born in New York in 1947, he veered into architectural painting when he was taken on by the London office of Richard Dixon — now part of Dixon Jones, the firm responsible for, among other projects, the Royal Opera House and the redesign of Exhibition Road. With an eye for detail, he has completed capriccios displaying the total built corpus of Hawksmoor, Cockerell, and, most recently, Vanbrugh, while the National Trust also commissioned him to paint a capriccio of all the houses currently within their care.

More of his work can be viewed at the website of Plus One Gallery, and a book of his paintings has been published by Philip Wilson. (more…)

Happy Christmas

Happy Christmas

and a

Blessed New Year

I wish all our readers the very best for this Christmas season and I hope we will all enjoy innumerable blessings in this coming year.

Krige at Bonhams

HAVING UNEXPECTEDLY been granted a day off (two, actually) I was quite content popping over to New Bond Street yesterday just in the nick of time to see Bonhams’ South African Sale before they went up for auction today. Out of pure ignorance, I used to think South African art was all mediocre before slowly discovering its small but noteworthy patches of brilliance. Francois Krige is one of them. Of the three galleries at Bonhams devoted to the South African Sale (Part II, strictly speaking) one of them darkened with individual lights highlighting the particular pieces hanging on the walls. (more…)

Bo Bartlett

THERE IS SOMETHING vigorously American about the art of Bo Bartlett. The modern realist was born in Columbus, Georgia, and studied in Italy under the Arthur Ross Award laureate Ben Long (one of the “greatest draughtsman of the twentieth century” according to Philippe de Montebello) before moving on to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. After completing a filmmaking degree at New York University, Bartlett embarked upon a five-year process creating a film covering the life and works of Andrew Wyeth, in collaboration with the artist’s wife Betsy. The artist’s work certainly shows the influence of Wyeth, as well as other American artists like Thomas Eakins, Edward Hopper, and Winslow Homer.

Hopper’s works, I’ve always found, have a particular quality of still abandonment, as if the scenes he depicts are living but just abandoned five minutes ago. Bo Bartlett’s paintings have a similar feel: they often exude a slight air of uncertainty and disquiet. There’s the looming threat of anarchy in The End of the 20th Century, also insinuated in So Far, as well as the reversal of the grounded American flag implied in Cradle. Other paintings, like Calling and Deer are peans to the animal kingdom. Still more are disturbingly quiet odes to the American coast — Bartlett divides his time between Puget Sound on the Pacific and Maine on the Atlantic. Whether beautiful portents of doom or eery celebrations of American life, the viewer suspects that there are stories not being told, and that the artist’s paintings conceal as much as they reveal. (more…)

The New Zealand Half-Crown

In the 1930s, New Zealand devalued its pound in relation to sterling and a whole new series of coinage and bank notes were introduced under the authority of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand. The government commissioned the accomplished English numismatic artist George Kruger Gray to design the dominion’s new coinage, which included this very handsome half-crown. It’s a splendid convergence between Maori and European design, two cooperating strains of New Zealand’s national culture. The country’s shield of arms is topped by a Tudor crown and flanked by indigenous motifs. (more…)

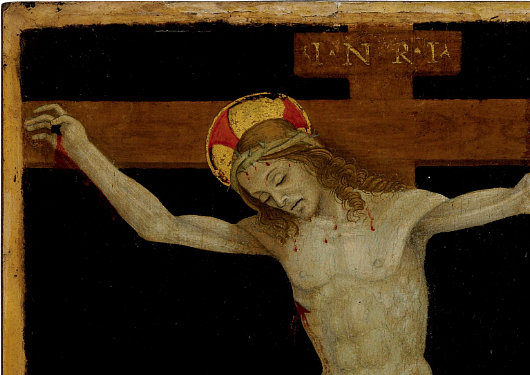

Old Master Paintings at Sotheby’s

A Florentine Artist, The Madonna & Child Enthroned Flanked by Saints Bridget & Michael

1450; Tempera on panel, 72 in. x 85 in.

QUITE A FEW interesting pieces up for auction today as part of Old Master Week at Sotheby’s in New York. The above altarpiece has been attributed to various artists. For much of its life was called the Poggibonsi Triptych, but scholars now believe it to be the work of the Master of Pratovecchio. This attribution was supported by no less an authority than Roberto Longhi, who (as the catalogue notes point out) “considered him an artist of note who contributed to the Florentine transition from the early fifteenth-century serenity and intimacy of Fra Angelico and Filippo Lippi to the more dynamic forms found later in the century.”

The altarpiece, commissioned from a certain Giovanni di Francesco in 1439, was acquired by the J. Paul Getty Museum in California, which is now auctioning to raise funds for future acquisitions. (more…)

Christopher Rådlund

My first encounter with the art of Christopher Rådlund was through the website of a friend. Bill Coyle is a poet and translator whose knowledge of the Swedish language gives him an insight into the rich and ingenious Scandinavian world. His January 2010 New Criterion article on the Swedish “retrogarde” was a fascinating insight into what is arguably one of the most fruitful multi-disciplinary artistic movements in Europe today, left almost completely unreported upon in the English-speaking world. Bill’s website displays one of Rådlund’s painting.

Christopher Rådlund was born in Gothenburg, Sweden in 1970 and now lives and works in the Norwegian capital of Oslo. In muffled tones, his paintings exhibit a melancholic coldness, like a modern baring-down of Caspar David Friedrich. Here is a small selection of his haunting but beautiful work. (more…)

David Goldblatt: Structures

“THE FIRST GROUP of photographs that I attempted of structures,” writes photographer David Goldblatt, “was a series made in 1961 on places of worship on the Witwatersrand. I came to this from two starting points. The first was a fascination with the idea of faith. Notwithstanding recurrent nightmares during childhood about the infiniteness of everlasting hellfire and uncertainty over the domicile of my unbaptised Jewish soul in the hereafter, arising from an otherwise happy primary school education by nuns, I don’t think I was ever able to believe in or pray to the deity with much conviction — except momentarily under extreme threat of imminent disaster. Neither nuns nor rabbi could ever enable me to transcend the banal with that leap of faith required of true believers. … I was — am — then, generally sceptical of believers’ beliefs but also in awe, and sometimes envious, of their ability to believe. If blind, unreasoning faith often repels me it sometimes moves and always intrigues.”

“Thus it was endlessly mysterious, even incredible to me that people — for the most part ‘ordinary’, ‘practical’ people, probably not much given to abstruse thought and discussion — should pour such effort and resource into the erection of structures devoted to so abstract an idea as God.” The photographer, understandably, doesn’t understand that, for we Christians, God is no less abstract than our father, mother, or neighbour down the street. “The ubiquity and persistence of the phenomenon, the immensity of humankind’s investment in God was to me quite awesome.”

“The second starting point for this early series of photographs of structures was an inchoate but growing awareness that whereas some structures seemed quite detached from this place, the Witwatersrand or, more broadly, South Africa, others grew almost viscerally from it. This seemed to have less to do with architecture than with indefinable qualities of ‘belonging’. I wanted to explore these notions and bring them into the light with the camera.” (more…)

Mauritshuis Digs Deep

Art Gallery in the Heart of the Hague Unveils Expansion Plans

WELL, NOT THAT deep, really. The Mauritshuis museum in the Hague recently unveiled its plans to expand underground and across the street into a neighbouring building. The square-footage of the museum will double after the completion of the new project, which will include a new entrance, exhibition hall, café, and lecture theatre. The entrance to the museum, currently accessed from the side street, will return to the front of the Mauritshuis but underground rather than through the main doorway on the ground floor.

The building was originally constructed between 1636 and 1641 for Johan Maurits, Prince of Nassau-Siegen next to the Binnenhof palace. At the time, Prince Johan Maurits (a cousin of the stadtholder Frederik Henrik, Prince of Orange) was governor of the New Holland, the Dutch colony in Brazil. In 1820, the palace was purchased by the government to house the Royal Cabinet of Paintings. The Mauritshuis art museum was separated from the state by being transformed into a private foundation which enjoys the use of the building and the art collection on long-loan from the government. (more…)

A book review in the Weekly Standard

While my admittedly small work on the Namibian jugendstil was recently published in Catalan, those who are interested in my review of Xander van Eck’s Clandestine Splendor: Paintings for the Catholic Church in the Dutch Republic can read it in the latest edition of the Weekly Standard.

Unfortunately the magazine’s website is mostly behind a paywall, so readers will have to swing by their local newsstand to obtain a copy.

The Academic Portraits of Cyril Coetzee

A Selection of University Portraiture by the South African Painter

THE ART SCENE in South Africa is widely varied in both style and quality, and the individual artist who is devoted solely to a single school is almost rare. The works of Cyril Coetzee (born in 1959) vary from quasi-figurative explorations of colour dynamics to multi-layered, almost mythological narrative paintings. His academic research at Rhodes University, located in his Eastern Cape hometown of Grahamstown, explored anthroposophic colour theory, so it’s no surprise part of his further studies were undertaken at the Goetheanum in Dornach, Switzerland (one of the sites covered in Stephen Klimczuk & Gerald Warner of Craigenmaddie’s Secret Places, Hidden Sanctuaries). Coetzee’s corpus also include a number of purely figurative portraits, many of which were commissioned by places of learning in South Africa. (more…)

Come to Finland

Travel Advertising from the Golden Age of Poster Design

FINLAND IS HIGH on my list of places to visit once I am re-situated across the pond, mainly because of the exceptional warmth and charm of the Finns I am blessed enough to call my friends. If the Finns themselves weren’t reason enough to visit the Land of the Midnight Sun, journalist & travel historian Magnus Londen has teamed up with copywriter Joakim Enegren and web operative Ant Simons to compile Come to Finland: Posters & Travel Tales 1851-1965. The art of poster design is one sadly neglected today, when advertising has developed into myriad other more pervasive yet less impressive forms. The book’s closing date, 1965, roughly marks the end of the golden years of poster design. Visitors to the book’s website can order postcards of the posters featured in the book, or copies of the posters themselves, more of which the dedicated poster-hunting authors are continually discovering. (more…)

Alexander Stoddart: “An Elite for All”

Scotland’s national newspaper interviews Scotland’s national sculptor

By SUSAN MANSFIELD

The Scotsman | 22 November 2008

ALEXANDER STODDART welcomes me into his studio, and into the 19th century. “It hasn’t gone away, you see,” he says, brightly. “The 19th century is not a period in time, it’s a state of mind.”

Indeed, if one could visit the workshop of one of the great monumentalists of a century ago, it might look a lot like this: plaster casts in various stages of assembly; imperious figures missing limbs or, occasionally, a head; bags of clay which until recently were a working model of physicist James Clerk Maxwell.

Stoddart is Scotland’s premier neo-classical sculptor, the man who made the figures of Adam Smith and David Hume for Edinburgh’s Royal Mile, Robert Burns for Kilmarnock, the beautiful Robert Louis Stevenson memorial on the capital’s Corstorphine Road. He’s 49, but looks boyish, with his sandy hair and dusty lab coat cut off at the elbows. He is a man of swift, enthusiastic intelligence, rarely still, and almost never silent.

Despite once being dismissed by the Scottish Arts Council as “backward-looking, historicist and not reflecting contemporary trends”, Stoddart is busy. Around us are the plastercasts of past commissions: immense allegorical figures for the £6 million Millennium Arch in Atlanta, Georgia; religious commissions for a mysterious private client who has her own chapel “somewhere in North Britain”; parts of 70ft frieze for Buckingham Palace. A bust of Pope John Paul II for a Chicago seminary.

Soon they will be joined by James Clerk Maxwell, whose statue, commissioned by the Royal Society of Edinburgh, will be unveiled on Tuesday at the East End of Edinburgh’s George Street. Stoddart is thrilled to be sharing a street with 19th-century sculptural greats like John Steel’s Thomas Chalmers. “It’s the greatest honour to be anywhere near the company of Steel.”

And he is ready and waiting for the next question, the one about relevance. (more…)

‘Handmade’ by Xavi García

‘A reaction to the soullessness of digital design’

Not many artists or designers have a business degree from Salamanca or studied management in Gothenburg. Xavi García has, though, and it’s obvious his grounding in the financial realm had an influence on his personal art project ‘Handmade’ — a banknote meticulously created by hand using drypoint, screenprinting, and stamps on newsprint. García describes the project as “a reaction to the soullessness of digital design”. (more…)

Christen Købke in London

THROUGH JUNE 13, the National Gallery in London is exhibiting “Christen Købke: Danish Master of Light”, a small show of the neglected Danish Golden Age painter but the first exhibition exclusively of his works outside of Denmark. “Kobke generally chooses the quietest corner, or a view from the side,” writes Waldemar Januszczak in The Times. “What fascinates him is the way light falls on the old stones, or the tufts of grass growing between the cracks. Throughout his art, whether he is painting landscapes or people, Købke seems always to be noticing the decay of the world he grew up in.” Januszczak suggests that the warmth of Købke’s work is in reaction to the turbulence of his country’s position in Europe at the time — Denmark backed the wrong horse in the Napoleonic wars and turned to neutrality, only to face a pre-emptive attack by the British in which Copenhagen was ferociously bombarded. The painter was born three years after this humiliation, and at age 12 began his studies at the Royal Danish Academy, where he studied under Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg, the ‘Father of Danish painting’.

The talented Købke painted portraits, landscapes, and other scenes. The show at the National Gallery includes my favourite Købke portrait, that of his friend and fellow artist, the landscape painter Frederik Hansen Sødring, on loan from Copenhagen’s Hirschsprung Collection.

His capability aside, what I like about Købke is that he is a certifiable local boy, rarely straying from the vicinity of his native Copenhagen except for the period of study in Italy required of the academically trained artist. His portraits are of his family and his friends, his landscapes of nearby rustic lanes and royal castles. A shame he died of pneumonia just 37 years old.

I haven’t had the chance to view any of his works in the flesh, but Londoners might want to avail themselves of this rare chance to see most of Købke’s capable work while on show in the metropolis. (more…)

Hans Laagland

Oil on wood, 1980

“It does not matter what the artist paints, but how he paints it,” proclaims the painter Hans Laagland. “That is why Rubens is a genius while Picasso’s work is passable.” Laagland, a Fleming himself, is one of the scant few artists in our day who paint in the grand style of the Flemish baroque master. He was born in Belgium’s Dutch province in 1965 and took up the brush and easel when ten years old. The young boy quickly developed a fascination with Rubens, considering and absorbing his works in the neighbouring city of Antwerp. Laagland’s emphasis is on traditional craftsmanship, painting in oils on wood panel, investigating and recreating the Old-Dutch lead white used by Rembrandt and the vermilion of Rubens. With a particularly capable hand at portraits, his work can be seen everywhere from the Norbertine abbey at Postel to the Belgian parliament in Brussels.

“It has been downhill ever since Rubens,” the painter says. Rembrandt — “Rubens’s disabled cousin” according to Laagland — was the last great painter; “What comes after him no longer has any significance.” Those versed in the Netherlandic tongue can read Mr. Laagland expounding upon his artistic ideas in De Kunstverduistering (“The Eclipse of Art”), his extended essay on art and painting now published as a book by KEI Zutphen. (more…)

A Wander Through the V&A

When on earth was the last time I was in the V&A? To be honest, I’ve no idea, though I’m certain my first visit was (like that of many others) as a wee one, the summer after kindergarten to be precise. It’s a stonking great place with tons of stuff in it, and one of the startling few that deal with architecture as a subject in its own right. (A fact which wins admiration in the heart of this architecture fan).

When on earth was the last time I was in the V&A? To be honest, I’ve no idea, though I’m certain my first visit was (like that of many others) as a wee one, the summer after kindergarten to be precise. It’s a stonking great place with tons of stuff in it, and one of the startling few that deal with architecture as a subject in its own right. (A fact which wins admiration in the heart of this architecture fan).

Of course the Victoria & Albert Museum has been fresh in the minds of many most recently for the re-opening of its Medieval & Renaissance sculpture galleries. The new arrangement cost over £30 million, took seven years to complete, and includes ten new display rooms displaying, as the Guardian put it, “a world of ravishing luxury”. So it seemed silly not to have a little wander round the South Ken institution yesterday, especially since it was a rainy afternoon. (more…)

Old Master & 19th Century at Christie’s

Being something of an auction-house dilettante — I last brought you a virtual update from the Dublin bidding chambers — there are a number of works up for grabs in tomorrow’s Old Master & 19th Century Paintings, Drawings, and Watercolors auction at Christie’s here in New York that caught my eye. A few other items sold in recent auctions follow at the bottom. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories