Art

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Marian Chashuble

Now in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, it was embroidered by the Sisters of Bethany, a Protestant order of nuns based in Clerkenwell. The Sisters specialised in church vestments and embroidery, and this object is believed to have been produced between 1909 and 1912.

Fr Anthony Symondson SJ has written in greater depth about Comper and the Sisters of Bethany here.

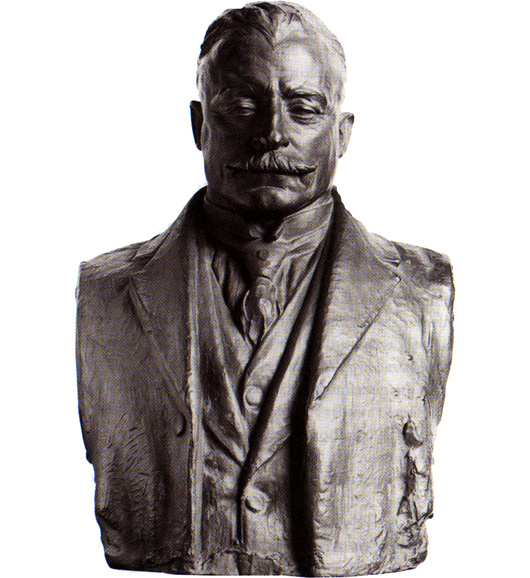

Albert Power & Arthur Griffith

These days the Irish sculptor Albert Power is very rarely spoken of, and I can’t claim to know much about this bronze bust he did of the founder of the original Sinn Féin, Arthur Griffith.

It might be in the National Gallery in Dublin, though I didn’t notice it when I nipped in there with my sister the other day. More likely it is in Leinster House, where there are other busts of prominent figures of 1916-1921 by Albert Power and the better-known Oliver Sheppard.

Unlike Sheppard, Power was a Catholic, which is probably why he was chosen to sculpt the funerary monument of Archbishop Walsh of Dublin who died in 1921. He submitted designs for the new Irish coinage but the Free State wisely chose the far superior set designed by the English sculptor Percy Metcalfe.

As for the subject of this work of art, the Royal Irish Academy’s Dictionary of Irish Biography describes Griffith as “a lucid writer with a vivid turn of phrase”.

The first newspaper he edited was in South Africa where he took the helm of the Middelburg Courant in 1897, attempting to persuade the English-speaking readers with his Boer-friendly views. “I eventually managed to kill the paper,” Griffith wrote, “as the British withdrew their support, and the Dutchmen didn’t bother reading a journal printed in English – the Dutch were quite right.”

Griffith founded Sinn Féin more as a pressure group to support his pet project of reviving the “King, Lords, and Commons” of Ireland, influenced by the Austro-Hungarian Ausgleich of 1867. Independence, he argued, would satisfy the nationalists, while the shared monarchy would keep the unionists happy. In the event, neither half were much enthused by the prospect.

In the aftermath of 1916, Griffith came into his own as a leader and statesman rather than an agitating journalist. His role in the War of Independence and the Treaty negotiations is well known. Without his persuasive arguments in debates, it is highly unlikely the Dáil would have approved the Treaty.

Gloomy civil war soon overshadowed everything, but Griffith died of a cerebral haemorrhage on 12 August 1922 – just ten days before Collins was killed in ambush at Béal na Bláth.

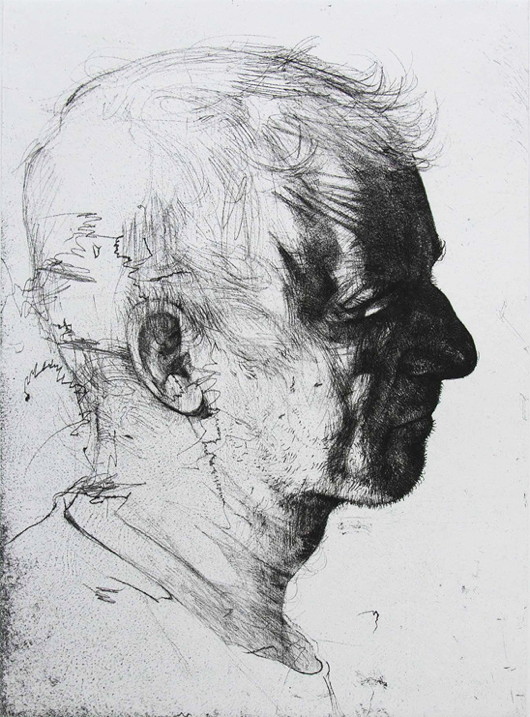

Lionel Smit

Suid-Afrikaanse portretskilder

Een van die mees geskoolde portretskilders vandag is die Pretoriaanse kunstenaar Lionel Smit (geb. 1982).

’n Skilder en beeldhouer, Mnr Smit woon en werk in Kaapstad en is die wenner van ’n ministeriële toekenning vir bydrae tot visuele kuns van die Wes-Kaapse regering. Sy werk is reeds ingesluit in die visuele kunste eksamen vir die Nasionale Senior Sertifikaat. Nie sleg vir ’n kêrel in sy dertigerjare!

Smit se skilderye herriner my aan die werk van die Engelse skilder Catherine Goodman. Hier is net sommige van sy portrette.

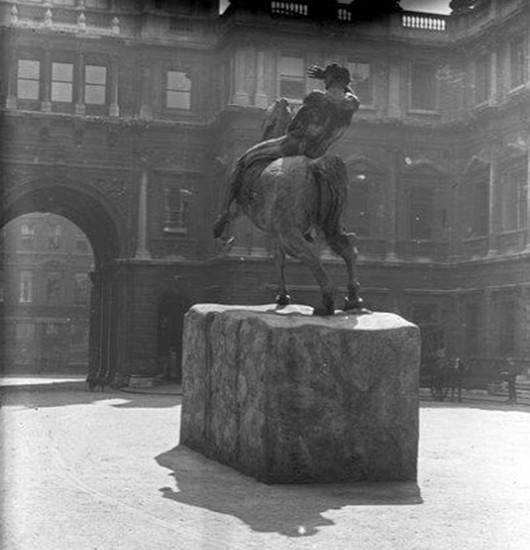

Physical Energy

I came across it by surprise one day, walking through the park. It was almost eerie — all the more so for being unexpected. George Frederic Watts’s sculpture “Physical Energy” was well known to me when I lived in South Africa as it graces the Rhodes Memorial in Cape Town — a rough Greek temple staring out northwards into the vast continent of Africa, as Rhodes himself liked to do.

Unknown to me, another cast of the statue was made and given to the British government, which placed it in Kensington Gardens. It was this copy I stumbled upon while traversing the park to Lily H’s drinks party in the garden of Leinster Square.

It is one of the most aptly named sculptures I can think of, as there is a raw brutish physicality to it, and somehow a sense of tremendous force, power, and energy. Watts was primarily a painter, so that he achieved this great work of sculpture is all the more remarkable. I don’t actually like it: there is something uncomforting and almost vulgar about it, or perhaps just taboo. (Like Rhodes himself.) But it is amazing all the same.

While “Physical Energy” is primarily associated with Cecil Rhodes it was not commissioned in his honour. Watts conceived it in 1886 after having done an equestrian statue for the Duke of Westminster. The first cast wasn’t made until 1902 and was exhibited at the Royal Academy for the first time in 1904 (above).

From there it made its way to Cape Town where it stands today a vital component of the monument to Rhodes. (It even features as the crest on Rhodes University’s coat of arms.) The second cast from 1907 is this one that sits in Kensington Gardens, while a third cast from 1959 now sits beside the National Archives of Zimbabwe in Harare.

This year the Watts Gallery in Surrey commissioned a fourth cast to commemorate the two-hundredth anniversary of the artist’s birth — and that cast now flaunts its bronze in the courtyard of the Royal Academy. It remains on view until the Cusackian birthday in March 2018.

Gallen-Kallela at the National Gallery

From November 15 until February of next year, the National Gallery here in London will mark the centenary of Finnish independence with a showing of the works of Akseli Gallen-Kallela. The Finnish painter is best known for his depictions of the Kalevala, the national epic compiled by Lönnrot and an influence on Tolkien.

The National Gallery, however, has focused on bringing together all four versions of Gallen-Kallela’s painting of Lake Keitele (alongside similar works by the artist). As a Swedish-speaking Finn, he signed the painting with his original Swedish name, Axel Waldemar Gallén, which he later Finnicised in 1907.

During Finland’s Civil War, Gallen-Kallela and his son Jorma both took up arms on the side of the Whites, who defended the country from the Soviet-backed Reds. The artist (below) served as adjutant to the regent of the kingdom, Gen Mannerheim, who asked him to design the flag, uniforms, and decorations of the new state. His student Eric O. Ehrström designed a crown for the kingdom, but eventually a republican form of government was decided upon and it wasn’t til the 1980s that a mock-up of the crown was actually crafted.

Having lived in Berlin and Kenya as well as having toured the United States, Gallen-Kallela’s influences were varied but he found the story and scenery of his homeland the most compelling of all. A fitting tribute to Finland in her hundredth year of statehood.

The Queen

1992; Oil on canvas, 96 in. x 60 in.

Marinus Willett

In one of the galleries of the Metropolitan Museum’s American wing, behind the Tuckahoe-marble façade of the old Assay Office (moved here from Wall Street), hangs this portrait of Col. Marinus Willett of the Continental Army’s 5th New York Regiment.

Born in 1740, the second of thirteen children, Willett attended King’s College before being commissioned a lieutenant in a New York provincial regiment during the Seven Years’ War (or French and Indian War as it’s known more locally). (more…)

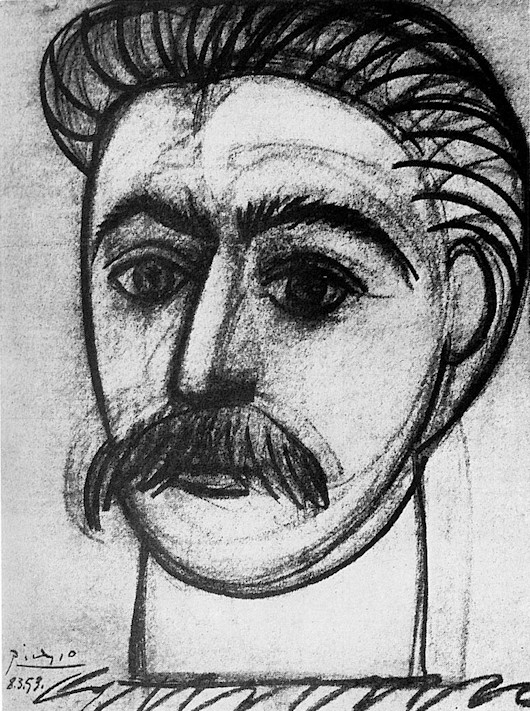

The Death of God the Father

When Stalin’s death was announced on Friday, 7 March 1953, Aragon called in Pierre Daix and rattled off a shopping list of features to honour Stalin in a special issue of Les Lettres françaises. […] Since Picasso had always refused to do a portrait of Stalin from a photograph, Daix sent a telegram to him at Vallauris saying, ‘Do whatever you want,’ and signed it ‘Aragon’.

Picasso’s drawing of Stalin, which depicted him as a curiously open-eyed young man, arrived at the very moment Les Lettres françaises went to press. Daix took the picture to Aragon. He admired it and said that the party would appreciate the gesture. While it was being set into the front page, office boys and typists crowded round the picture. Everyone thought it ‘worthy of Stalin’.

Daix was overjoyed to be the one who had commissioned Picasso’s first portrait of the Soviet leader and rushed it down to the printers. But a few hours later, when the edition had been run off, the mood in the building had completely changed to one of fear. Journalists from L’Humanité, passing by, spotted the drawing and cried out that it was unthinkable that any Communist publication should consider such a representation of ‘le Grand Staline’.

Pierre Daix promptly rang Aragon at his apartment; Elsa Triolet answered. She told him angrily that he was mad to have even thought of asking Picasso for such a drawing.

‘But really, Elsa,’ Daix broke in, ‘Stalin isn’t God the Father!’

‘Yes, he is, Pierre. Nobody’s going to reflect much about what this drawing of Picasso signifies. He hasn’t even deformed Stalin’s face. He’s even respected it. But he has dared to touch it. He has actually dared, Pierre, don’t you understand?’ […]

Antony Beevor & Artemis Cooper (1994, London)

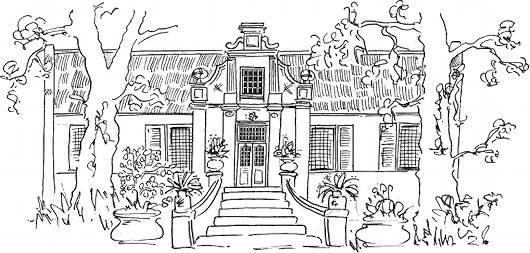

Muratie

The Stellenbosch estate of the artist Georg Paul Canitz

We had supper with Mr. Canitz, the painter, one Sunday night, by the light of candles in a fine Dutch candelabra, and drove back to Stellenbosch in moon light which had transformed the countryside into the most entrancing fairyland imaginable.

Great clumps of trees in unexpected places gave an eeriness to the white ribbon of road which stretched across the valley. The soft evening breeze of magic scents lulled us, and we drowsed to the hum of the car bearing us homeward.

That memory is still vivid to me so I shall turn from our Golden Road, and “…muse awhile, entoil’d in woofed phantasies.”

So the architect Rex Martienssen described a visit to Muratie, the home of the artist Georg Paul Canitz, in 1928. Canitz was a Saxon, born in Leipzig, where his parents had hoped he would pursue a military career. Both his zeal and talent as an artist appeared early on, and so he ended up at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts. After further studies in Italy, Paris, and the Netherlands, a chest ailment drove him to the interior of Südwestafrika in 1907.

Canitz healed quickly in the dry air but could not find a cure for the striking beauty of the new world around him. His wife and children were summoned from Germany, and three years later he moved to Stellenbosch after falling in love with the “City of Oaks”.

Canitz devoted himself to his passions: riding, painting, and teaching (both at his own art school and at the University). Riding to a party at Knorhoek one day he stumbled upon the little house and farm at Muratie and was quickly enamored of the place. It wasn’t long before he had purchased it and moved his family there.

G P Canitz

At Muratie, the painter developed a further art: that of winemaking. In this he was assisted by the legendary Dr Perold — first chair of viticulture at Stellenbosch. Canitz became a pioneer of the pinot noir grapes which have since become a South African staple. Perhaps even more he developed the skills of a kind and generous host, for which he was well reputed throughout South Africa. He would welcome friends and guests — among them Martienssen and his architectural students as cited above — throughout the year. In warmer months they came for the swimming pool and the breezy stoep, while in winter a fire awaited, or perhaps a few rounds of strong drink in the Kneipzimmer.

I like to think this was Canitz’s favourite room at Muratie: bedecked with benches, the light streaming in through a stained-glass windows, and the walls covered in naturalistic painting as well as graffitied signatures and sayings in German, Afrikaans, French, and Greek.

The painter died in 1958, leaving Muratie to his daughter, who in 1987 sold it to members of the Melck family who had owned it from 1763 to 1897. (The house was first built in 1685.) I suspect Canitz would have greatly appreciated his handiwork being passed back to those who had looked after the place for many generations before him. The Melcks, unsurprisingly, have a great reverance for the history of the estate. They even go so far as to leave the cobwebs which have accrued go undisturbed and ask visitors to do likewise.

And, even today, the wine still flows!

Master Mitsui’s Ink Garden

Daniel Mitsui is one of the most interesting artists out there, exhibiting a wide range of influences from the Celtic to the Oriental. Among his latest works is an ink drawing on a Catholic theme. As Daniel explains:

I received a commission to create a Catholic religious drawing in a Chinese style. These explorations into artistic traditions outside of European Christendom are always exciting, and China was new territory for me. When developing the concept for the project, I looked to one of the early missionaries to China, the Italian Jesuit Matteo Ricci.

Some time in the very early 17th century, Ricci gifted four European prints to the Chinese publisher Cheng Dayue: two engravings by Anthony Wierix from a series illustrating the Passion and Resurrection of Christ, another by the same artist reproducing the painting of the Virgin of Antigua in Seville Cathedral, and one by Crispin De Pas the Elder from a series illustrating the life of Lot.

Master Cheng copied these images into his Ink Garden, a model book of illustrations and calligraphy. The missionary saw this as a good opportunity to disseminate lessons in Christian doctrine and morality among the Chinese population.

Continue reading here.

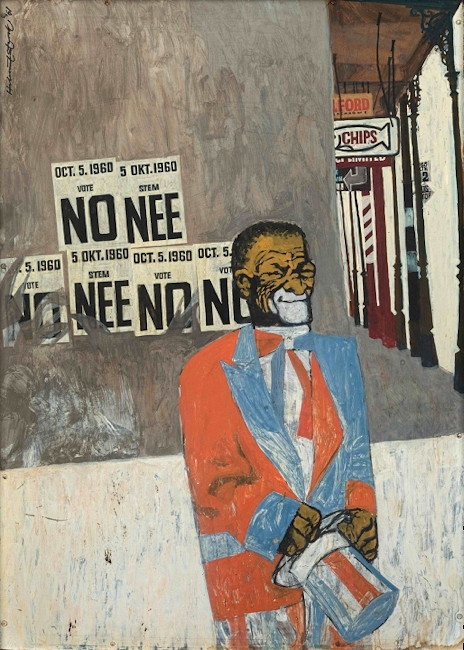

Alles Sal Reg Kom

1961; Acrylic on board, 34.8 in. x 24.8 in.

A man festively attired in a Tweede Nuwejaar outfit in patriotic colours (orange, white, and blue) stands in front of a side wall in Cape Town bearing monarchist posters urging voters to vote ‘No’ in the 1960 republic referendum.

The painting’s title – Alles Sal Reg Kom – means “everything will be alright”.

Wednesday 27 January

– Margaret Beaufort was one of the greatest women England ever produced, but her legacy has been plagued by misogyny combined with Protestant suspicion of her Catholic piety. Leanda de Lisle delves into the question of whether she was a hero or a villain.

– Speaking of powerful women, James Panero’s examines the monument to Joan of Arc on New York’s Riverside Drive. The artist was a female sculptor, Anna Hyatt Huntington, whose statue of El Cid in the forecourt of the Hispanic Society on Audubon Terrace is one of the finest sculptural arrangements in the New World.

– Lent is about to stare us in the face, but so far as I am concerned we are allowed to wallow in Christmas cheer until Candlemas comes on 2 February. Dr John C Rao (of St John’s University and the Roman Forum) offers us a reflection on the Christmas Crèche and its origins as Saint Francis’s giant “F.U.” to Cathar heretics, while putting the thinking behind that great saint’s actions in a modern context.

– It’s good to see neglected favourites receive a bit of unexpected attention. One such is the Irish writer George Russell, more often known by his pen name ‘Æ’. The Irish Ambassador to Great Britain, Dan Mulhall, begins a series on Irish writers and 1916 by looking at Æ in the context of the Rising.

One project that TCD or UCD – or anyone for that matter – needs to take on is digitising the entirety of The Irish Statesman, the journal mostly edited by Russell which presented a fascinating counterpoint to the more common narratives, first in 1919/20 and then from 1922 to 1930.

– And finally, some Goethe love from The New Yorker’s Adam Kirsch.

The Accession

c. 1911; Oil on canvas, 68 in. x 76.9 in.

A triumphant painting, but a last hurrah. The central figure is Sir Nevile Wilkinson, the last ever Ulster King of Arms & Principal Herald of Ireland, exercising the duties of his office by proclaiming the accession of the new king at Dublin Castle.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty and its legislative acts neglected to make provision for transferring this ancient office to the new Irish Free State, but Sir Nevile carried on regardless for nearly two decades, even issuing two dozen grants of arms on the day before his death in 1940.

After his death, the Oireachtas created the office of the Chief Herald of Ireland to continue the granting of arms, and in some sense the Chief Herald is a spiritual successor to the Ulster King of Arms.

View from a Window

1830; Oil on canvas, 15½ in. x 13½ in.

I love the underappreciated Biedermeier, whether in art or literature, and this is a very Biedermeier painting.

The painter’s father, Charles de Moreau, was an architect – indeed he designed the very building that the son depicts here. As it happens, the painting now hangs in the Wien Museum am Karlsplatz, across from the main building of the Imperial & Royal Polytechnic Institute (now the Vienna University of Technology) which his father also designed.

Nikolaus painted this scene when he was twenty five, and he died just four years later not having reached his thirtieth year.

Interior of the Groote Kerk

1916; Oil on canvas, 29½ in. x 24½ in.

Though the painting is just a hundred years old, Gwelo Goodman depicted the scene as if in the late seventeenth century — when the Groote Kerk was first built.

While the body of the church was replaced in the 1840s, the elders of this most senior Nederduits Gereformeerde gemeente wisely kept the stunning baroque pulpit, the work of the Cape’s greatest sculptor Anton Anreith.

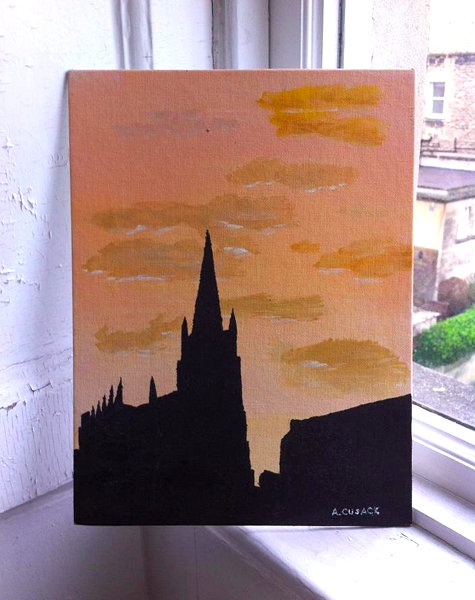

An Original Cusack

Much to my regret now, I never particularly learned nor pursued artistic skills, but this painting of St Patrick’s Church in Monaghan Town is one of the few fruits of art class from school days we’ve bothered preserving.

I think I was about 15 when this was done; the architecture was from a photo just to have something to stand out against the sunset. Our teacher was very good, but I was a poor student, and inattentive.

A Decade of Driehaus

A Carl Laubin capriccio pays tribute to the first decade of Driehaus laureates

THIS YEAR MARKED the tenth anniversary of the Driehaus Prize, the annual award honouring a living architect who has contributed to the field of traditional and classical architecture. To commemorate the first decade of the Prize, the architectural painter Carl Laubin was commissioned to produce a splendid capriccio depicting the works of the first ten Driehaus laureates.

As Witold Rybczynski, a member of the Driehaus panel of jurors, writes:

In the foreground is the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates, a bronze miniature of which is presented to each laureate. It’s fun to try and identify the individual works in this large (5½ by over 8 feet long) painting. But what is more striking is that Laubin has created a convincing urban landscape solely out of landmark buildings.

That, of course, is the advantage of classicism: however it is interpreted, it is a tradition that manages to produce a more or less coherent whole. Even Abdel-Wahed El Wakil’s mosque, standing next to a Seaside beach house by Robert A. M. Stern, doesn’t look too out of place.

The Driehaus Prize was founded in part as a rival to the more publicised Pritzker Prize awarded to modernist architects. But, Mr Rybczynski points out, the fundamental nature of modernist structures is that they thrive only as a visual contrast to buildings constructed in a traditional style.

Can one imagine a similar townscape of Pritzker Prize winners? Well, maybe with the work of some of the early laureates—Pei, Bunshaft, Tange, Siza—but modern buildings need a background of nineteenth and early twentieth century urbanism to shine. A town made up of only signature buildings by our current generation of stars would resemble a carnival or a theme park—Pritzkerland.

I’ve often thought this of the United Nations headquarters in New York, which, when it was first built, must have stood out brilliantly as a bright and fresh harbinger of a better future, but which has been rendered altogether rather boring by the construction of neighbouring buildings of third-rate plate-glass modernist designs.

The UN headquarters on the East River and Lever House on Park Avenue were breakthrough buildings, but the increasing replacement of their traditional stone-clad or brick neighbours by cheap, tawdry modernist structures has exposed how reliant this type of architecture — even when well-conceived and properly executed — is on being surrounded by a contrasting style. (more…)

Beauty and Revolution

“Schönheit und Revolution: Klassizismus 1770-1820”

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

WHEN IT COMES to styles, I am an omnivore. There are die-hard partisans, like Pugin, but I find the Baroque, the Gothic, the Classical — all are welcome to me. There is always some tiresome bore who, upon hearing any particular style of art or architecture praised, will immediately launch into a tirade against the more negative connotations commonly associated with that style. Gothic is close-minded! Mannerism is affected! The Biedermeier is bourgeois!

Well… ok… to an extent. But, in truth, we brush aside these pedants and appreciate whatever is beautiful wherever it is to be found. Art in its many forms is a giant sponge to squeeze and collect, savor, what comes out of it. (more…)

Grace Jones, Artist

Among the surprises in store at the Collectors’ Preview of the Olympia antiques fair on Monday night were two works by the actress Grace Jones. When I was a wee bairn, “A View to a Kill” was one of my favourite Bond films, and Jones played May Day, the frightening sidekick to Christopher Walken’s Zorin. Apparently Grace Jones studied art for a period, and Charles Plante Fine Arts has two pictures by her amongst their offering: ‘An Eskimo rowing a boat’ (Charcoal with mixed media, 49 inches by 43 inches) and ‘Untitled abstract composition 1983’ (Mixed media on paper, 60 inches by 67 inches).

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories