Art

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Patrick in Parliament

The Mosaic of Saint Patrick in the Palace of Westminster

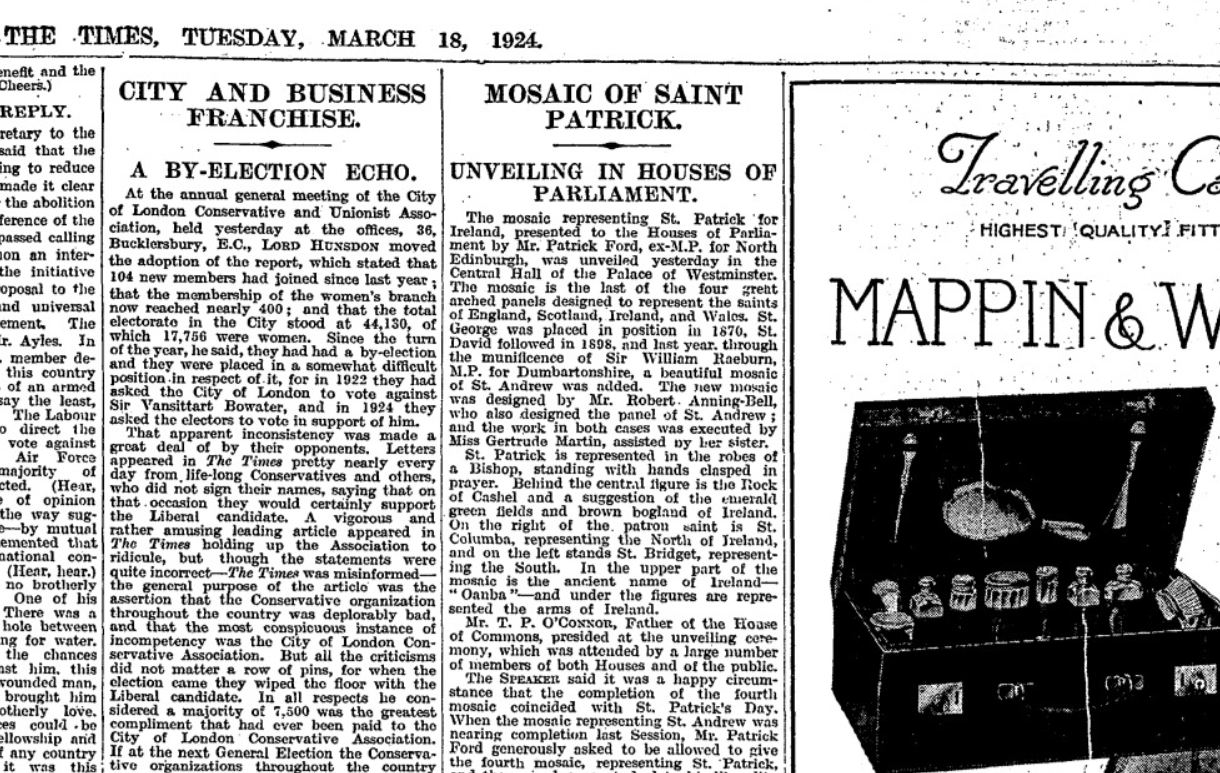

This feast of St Patrick marks the hundredth anniversary of the mosaic of Saint Patrick in the Central Lobby of the Houses of Parliament. At the heart of the Palace of Westminster, four great arches include mosaic representations of the patron saints of the home nations: George, David, Andrew, and Patrick.

The joke offered about these saints and their positioning is that St George stands over the entrance to the House of Lords, because the English all think they’re lords. St David guards the route to the House of Commons because, according to the Welsh, that is the house of great oratory and the Welsh are great orators. (The English, snobbishly, claim St David is there because the Welsh are all common.) St Andrew wisely guards the way to the bar (a place where many Scots are found), while St Patrick stands atop the exit, since most of Ireland has left the Union.

The mosaic of Saint Patrick came about thanks to the munificence of Patrick Ford, the sometime Edinburgh MP, in honour of his name-saint. Saint George had been completed in 1870 with Saint David following in 1898.

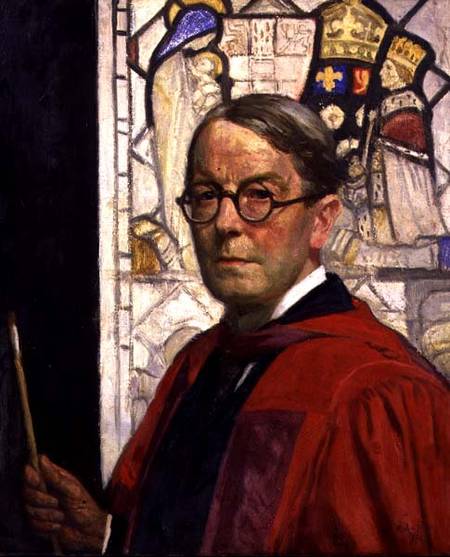

Sir William Raeburn MP commissioned the artist Robert Anning Bell (depicted right) to design the mosaic of Saint Andrew in 1922, which so impressed Patrick Ford that he decided to commission the same artist to depict the patron saint of Ireland.

Sir William Raeburn MP commissioned the artist Robert Anning Bell (depicted right) to design the mosaic of Saint Andrew in 1922, which so impressed Patrick Ford that he decided to commission the same artist to depict the patron saint of Ireland.

Anning Bell had earlier completed the mosaic on the tympanum of Westminster Cathedral from a sketch by the architect J.F. Bentley. Following his work in Central Lobby he also did a mosaic of Saint Stephen, King Stephen, and Saint Edward the Confessor in Saint Stephen’s Hall — the former House of Commons chamber.

In the mosaic, Saint Patrick is flanked by saints Columba and Brigid, with the Rock of Cashel behind him. As by this point Ireland had been partitioned, heraldic devices representing both Northern Ireland and the Irish Free State are present.

On St Patrick’s Day in 1924, the honour of the unveiling went to the Father of the House of Commons, who happened to be the great Irish nationalist politician T.P. O’Connor, then representing the English constituency of Liverpool Scotland (the only seat in Great Britain ever held by an Irish nationalist MP).

“That day,” The Times reported T.P.’s words at the unveiling, “in quite a thousand cities in the English-speaking world, Saint Patrick’s name and fame were being celebrated by gatherings of Irishmen and Irishwomen. Certainly he was the greatest unifying force in Ireland.”

“All questions of great rival nationalities were forgotten in that ceremony. From that sacred spot, the centre of the British Empire, there went forth a message of reconciliation and of peace between all parts of the great Commonwealth — none higher than the other, all coequal, and all, he hoped, to be joined in the bonds of common weal and common loyalty.”

T.P.’s remarks were greeting with cheers.

The Most Honourable the Marquess of Lincolnshire, Lord Great Chamberlain, accepted the ornamental addition to the royal palace of Westminster on behalf of His Majesty the King.

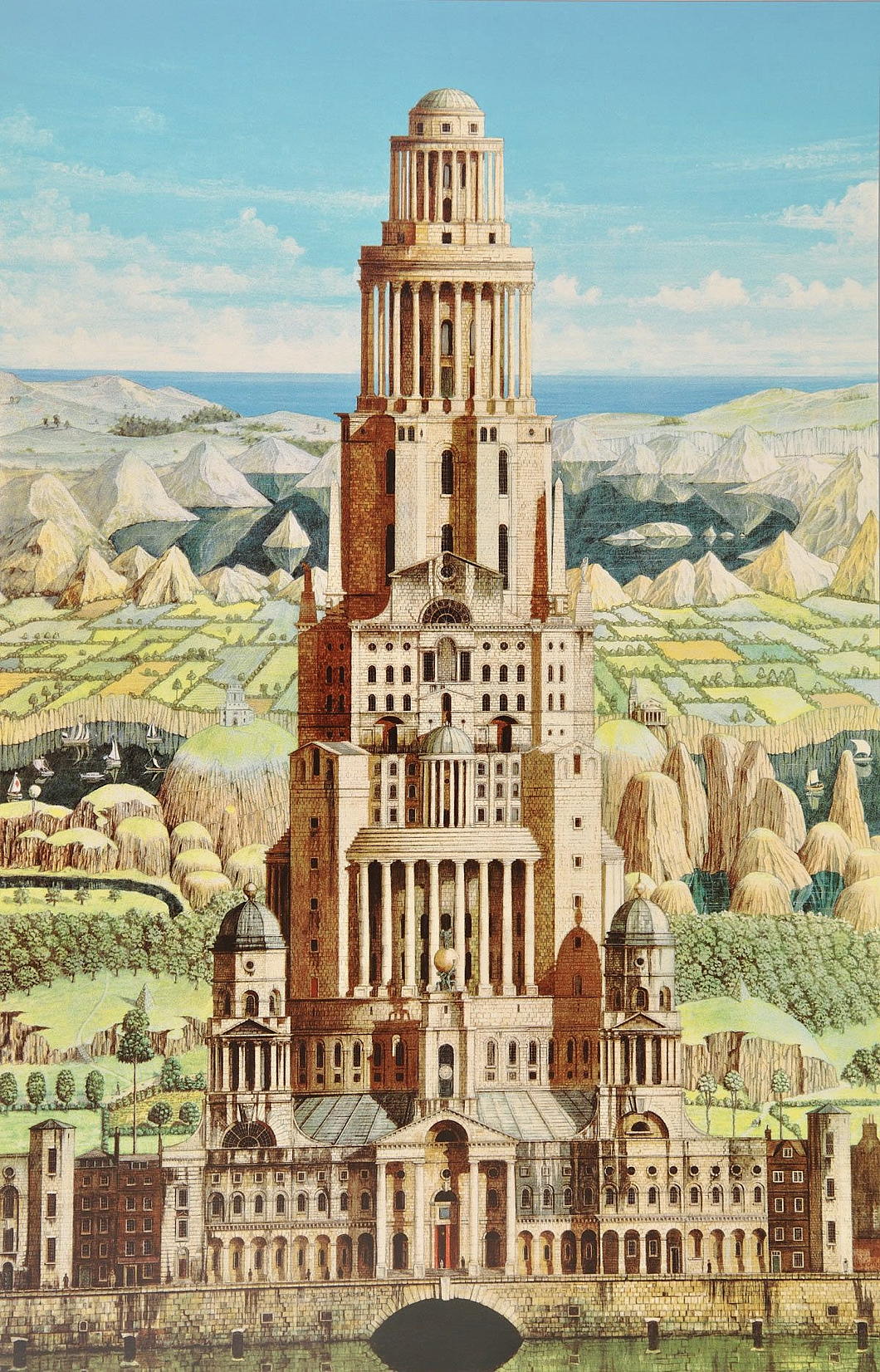

Hawksmoor’s Dream

27½ in. x 17¾ in.; 1987-1991

Andrew Ingamells is an excellent draughtsman who is probably the finest architectural artist in Britain today.

His depictions of Westminster Cathedral and the Brompton Oratory (amongst others) are in the Parliamentary Art Collection, and he has done Loggan-style portrayals of the colleges of Oxford and Cambridge as well as three of the four Inns of Court in London.

The above capriccio is a wonderful treat. I think someone should build it.

Canterbury Gate

10 in. x 16¼ in., 1799; Tate Collection

Turner’s painting captures Christ Church’s Canterbury Gate from Oriel Square. (As it happens, this is Canterbury Gate at Christ Church in Oxford and, conversely, there is a Christ Church Gate at Canterbury in Kent.)

Given the greenery of the vegetation, this is almost certainly not the work that inspired Betjeman to write his winter poem ‘On an Old-Fashioned Water-Colour of Oxford’:

A winter sunset on wet cobbles, where

By Canterbury Gate the fishtails flare.

Someone in Corpus reading for a first

Pulls down red blinds and flounders on, immers’d

In Hegel, heedless of the yellow glare

On porch and pinnacle and window square,

The brown stone crumbling where the skin has burst.

A late, last luncheon staggers out of Peck

And hires a hansom: from half-flooded grass

Returning athletes bark at what they see.

But we will mount the horse-tram’s upper deck

And wave salute to Buols’, as we pass

Bound for the Banbury Road in time for tea.

Articles of Note: 29 January 2024

A lively Doubleyoo-Ess once took me to lunch at the New Club and, in whispered tones, pointed out a gentleman sitting at another table.

“He is the world’s leading expert on the Scots tongue,” my friend explained.

“But he was excommunicated by all the other experts on Scots when he pointed out that eighty per cent of Scots words are interchangeable with Northumbrian English.”

Scots is fascinating for its closeness to English and its distinction. Those who’ve had the pleasure of tarrying awhile in the Netherlandic world (whether in Europe, the Cape of Good Hope, or elsewhere) can detect the odd affinities to Dutch and Afrikaans — reminding you that the North Sea was once a highway, not a barrier.

Luka Ivan Jukic has written an enlightening exploration of how and why Scotland lost its tongue.

Jukic contends there are no signs of revival, which I dispute. There is a much increased interest in the use of Scots, but it feels contrived and falls somewhat flat. If you take a look at the Scots column in The National newspaper, it comes across as the ravings of a kook something akin to Anglish.

■ Amongst the many of Scotland’s joys is the pleasure of just looking at its buildings.

Witold Rybczynski pleads “Give us something to look at!” in his account of why ornament matters in architecture.

■ The New York Post — founded by Alexander Hamilton in 1801 and thus the Empire State’s oldest and most venerable newspaper — reports that the world’s oldest and most venerable forest has been discovered right in the heart of the Catskill Mountains.

This is one of the most beautiful places in America, especially when the leaves begin to turn in autumn, and features widely in the old stories transcribed by Washington Irving and others.

The name of the Catskills is believed to be from the catamounts that used to roam the woods and bergs when our Dutch forefathers of old first arrived in the valley of the Hudson. Our earliest record of it is on a map by Nicolaes Visscher père from 1656 — and pleasingly the local magazine retains the old spelling in its name of Kaatskill Life.

This fossilised forest within the Catskills is believed to date from 385 million years ago (for those who doubt the Ussher chronology — and we remain open-minded ourselves) and was discovered at the bottom of an old quarry.

■ As a precocious teenager I remember a visit to the maritime museum in Rochefort on France’s Atlantic coast that included a fascinating display of the intricacies and accomplishments of global shipping, housed in the long old ropeworks that kept France’s navy afloat in the era of sail.

It’s all been kicking off in the Red Sea, which inspired Wessie du Toit to write that the shipping container is an uncanny symbol of modern life

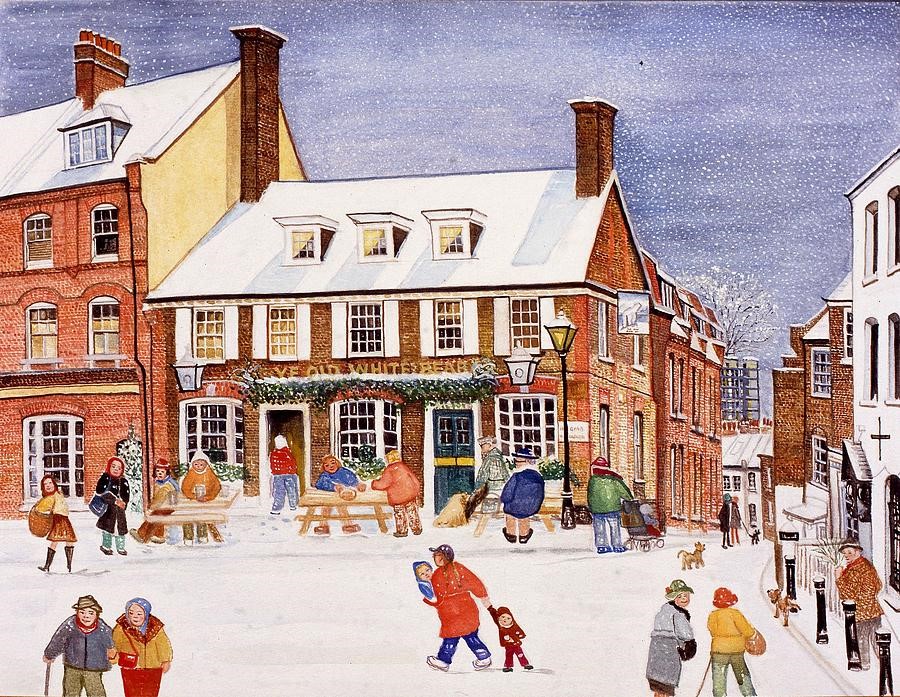

■ Some people claim there is no life outside of NW3, but as much a fan of Hampstead as I am, my first loyalty in London neighbourhoods is firmly lodged in Southwark. (Pimlico is high on the list, too.)

Many will pine for those precious late summer afternoons idly dawdling on the Heath, but Hampstead in winter has its distinct pleasures. For me, it’s curdling up with a pile of books beside the coal fire in the Old White Bear.

In the Christmas issue of The Oldie, Peter York wrote about the rise and fall of arty Hampstead.

■ One of our Hampstead mates is originally a West Country man and now finds himself even further west, studying law in California.

For a New Yorker, California is The Great Other. If not quite a rival, then certainly something we are always being compared against.

Naturally, one looks down on California, but also with a certain envy. If ever America had a golden moment when imperial might was combined with the simple goodness of life, it must have been coastal California from the 1930s to 1960s — with a hint of survival into the 1980s.

California’s decline is evident to all, though its power and influence is still vast (as the iPhone in your pocket proves). The Manhattan Institute recently devoted an entire issue to the question of Can California Be Golden Again?

I haven’t had a chance to read much of it, but I did enjoy Jordan McGillis’s article on how San Diego retains many of the qualities that once made California the envy of the world.

■ Peter Viereck ranks amongst the names of slightly neglected thinkers in the agora of American conservatism. Reading him always brings some insight, but I never knew much about the man himself.

Samuel Rubinstein supplies a fascinating account of the man and his thinking in Peter Viereck: Psychoanalyst of Nazism.

■ National treasure Peter Hitchens has spent his life hating the ogre Ted Heath, destroyer of worlds. I will never forgive him for what he did to England’s ancient counties and boroughs.

But Hitchens the Heath Hater, with his typically thoughtful approach, offers a reconsideration of the man.

■ All politics is local: Fred de Fossard writes about how EU-obsessed Lib Dems are ruining Bath rather than guarding one of the most precious jewels of English cities.

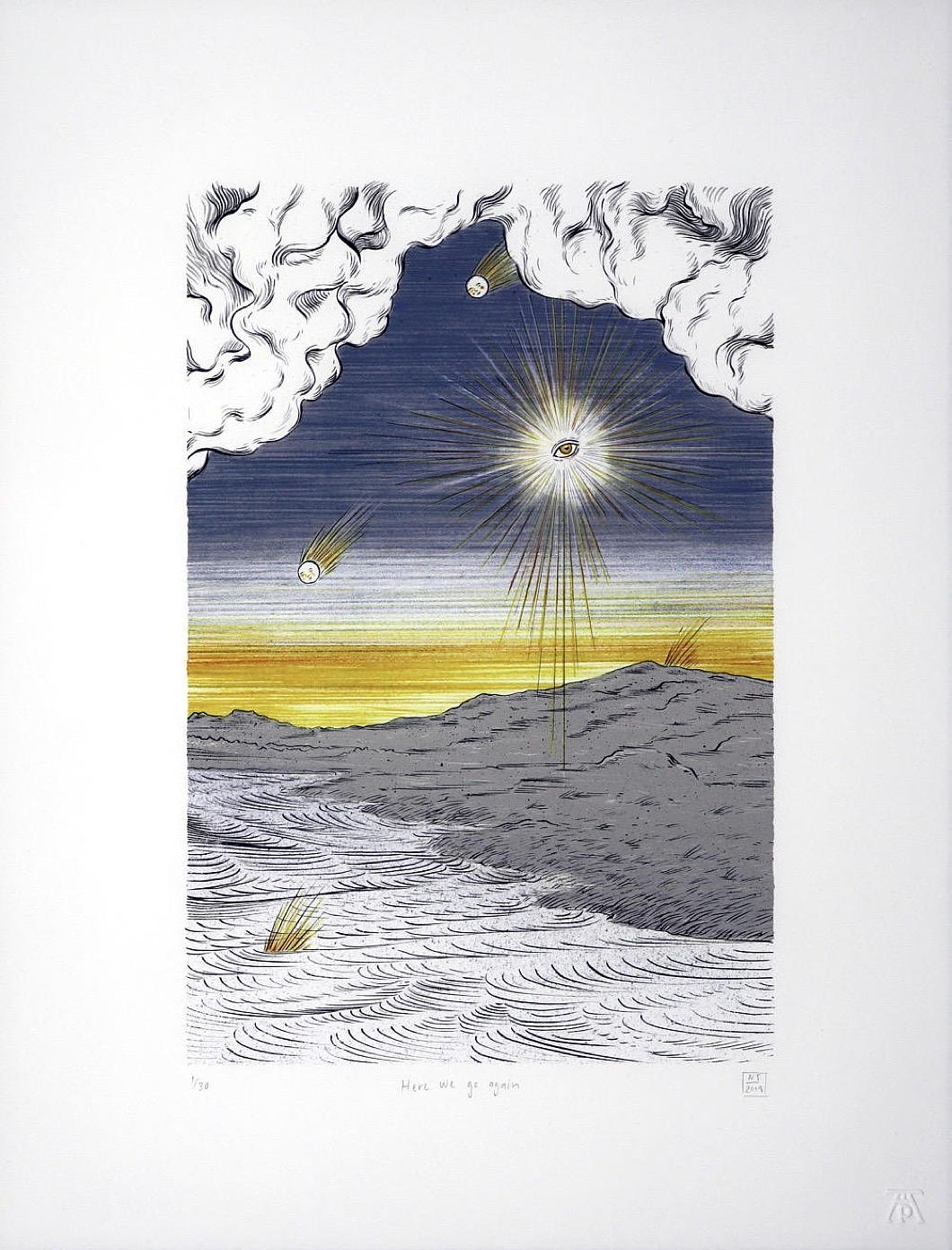

■ We leave you with this six-colour lithograph from the Pretoria-based artist Nina Torr entitled ‘Here we go again’ (an edition of thirty, available from the Artists’ Press):

Old Church, Paarl

The church in die Paarl is the third-oldest NGK congregation in South Africa, after the Groote Kerk in Cape Town and the Moederkerk in Stellenbosch. It is often known as the Strooidakkerk (straw-roof church) for obvious reasons.

This part of the Drakenstein was first settled by Huguenots, where the dominee Pierre Simond preached in French from the foundation of the church in 1691 until he returned to Europe in 1702.

Dom Miguel de Castro

During the 1640s, a conflict arose between Kongo’s pious and militarily successful King Garcia II and his vassal, the Count of Sonho. Seeking the help of the Dutch Republic and its stadtholder, the Count sent his cousin, Dom Miguel de Castro, to the Netherlands as an emissary.

Dom Miguel arrived at Flushing in June 1643 and proceeded to Middelburg where he was received by the Zealand chamber of the Dutch West India Company.

During the Kongo nobleman’s fortnight in Middelburg, the chamber commissioned these portraits of Dom Miguel and his two servants painted by Jasper Becx — or possibly by his brother Jeronimus.

The Zealand chamber gave the trio of portraits to Johan Maurits — Prince of Nassau-Siegen, governor of Dutch Brazil, and originator of the Mauritshuis — who in 1654 gave them to Frederik III of Denmark, along with twenty Brazilian paintings by Albert Eckhout.

A full-length portrait of Dom Miguel was taken back to Africa by him and, alas, is now lost.

Dom Miguel de Castro

Jaspar Beckx, c. 1643;

Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

Dom Miguel de Castro

Jaspar Beckx, c. 1643;

Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

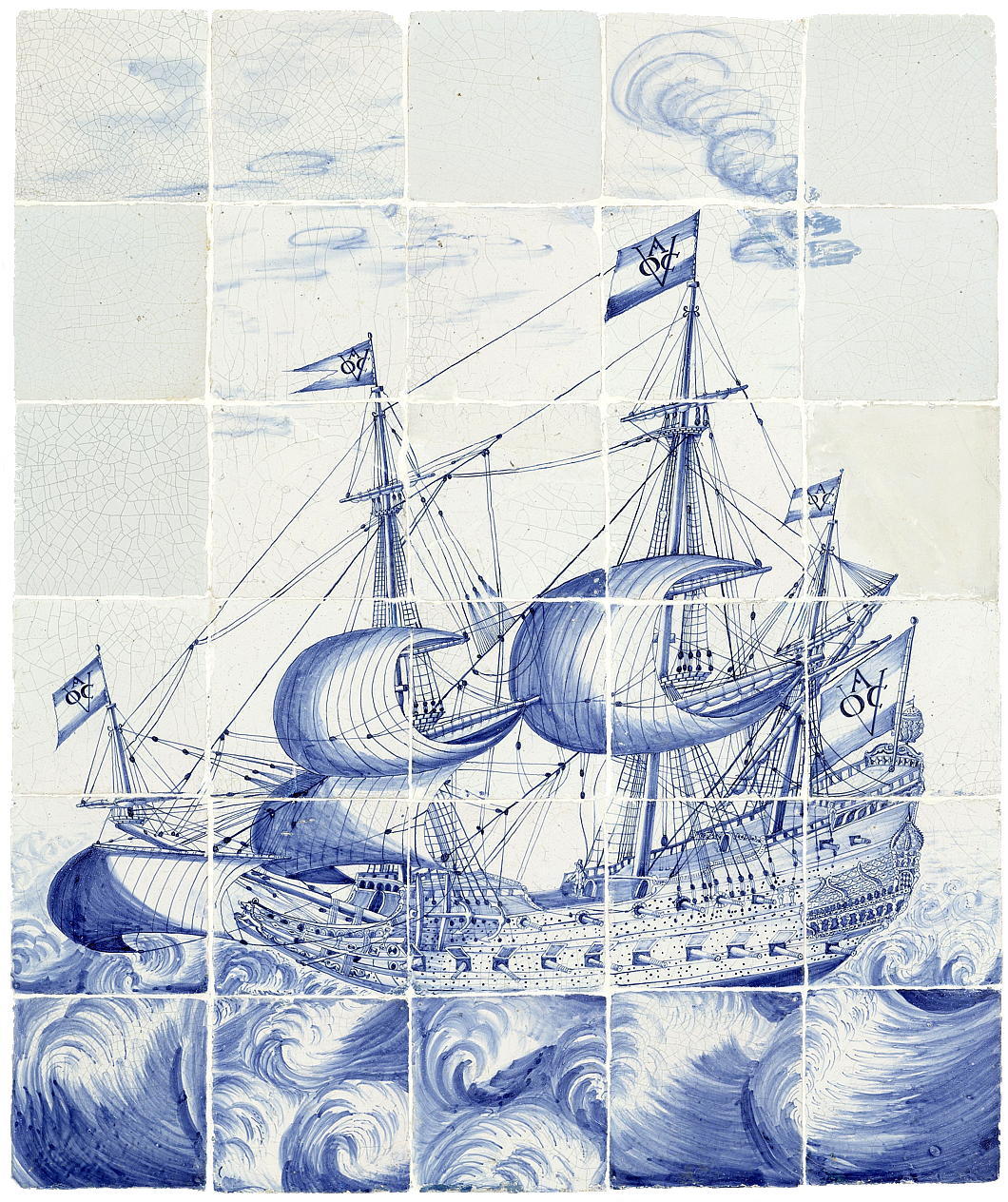

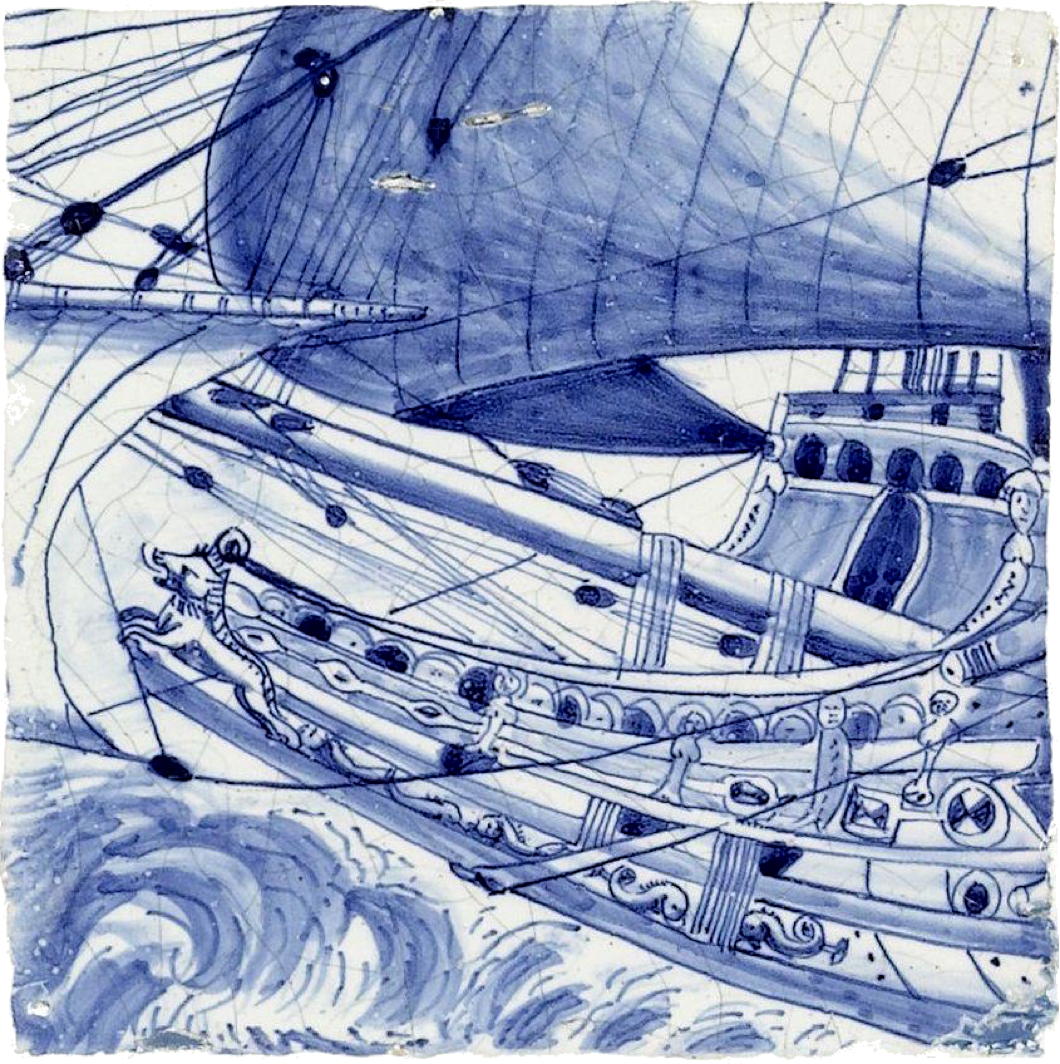

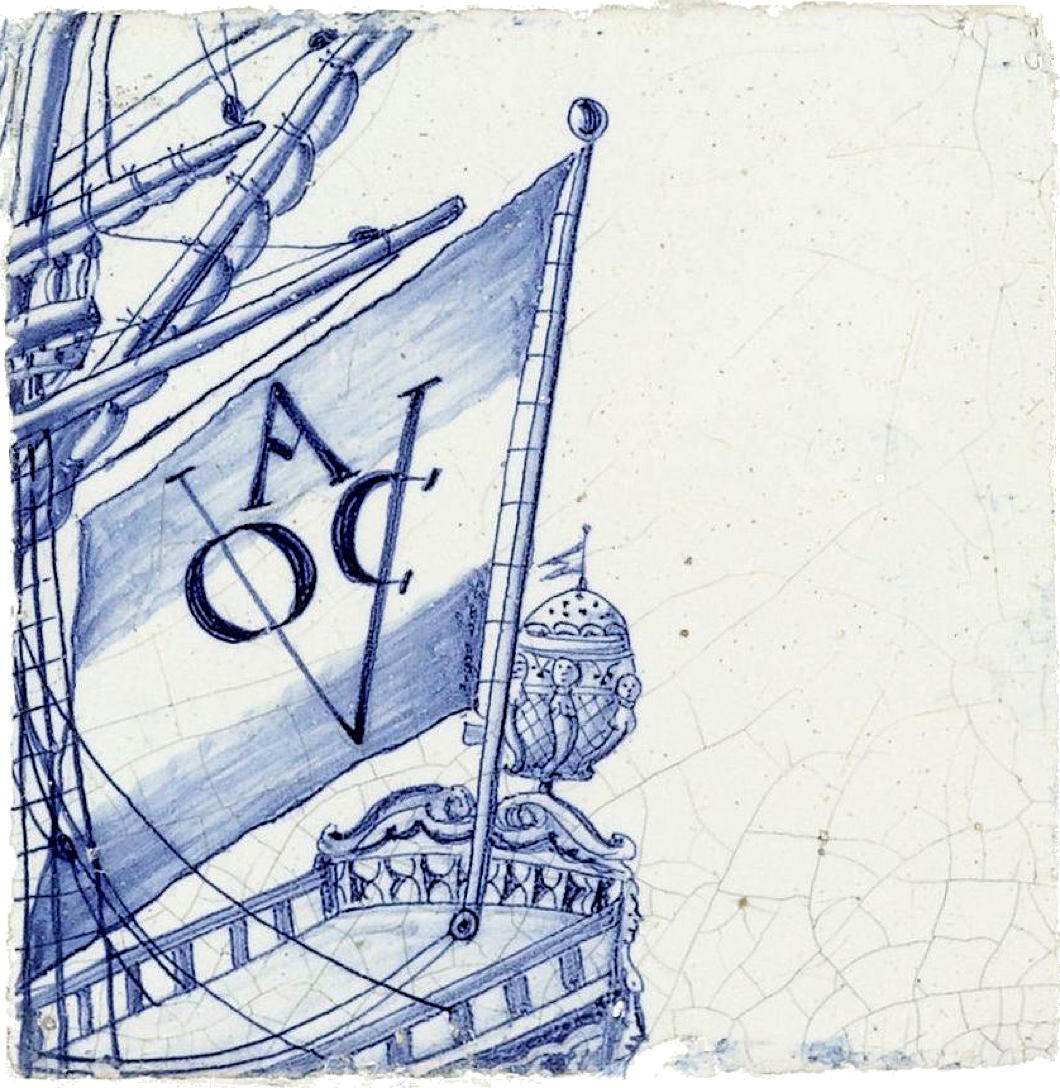

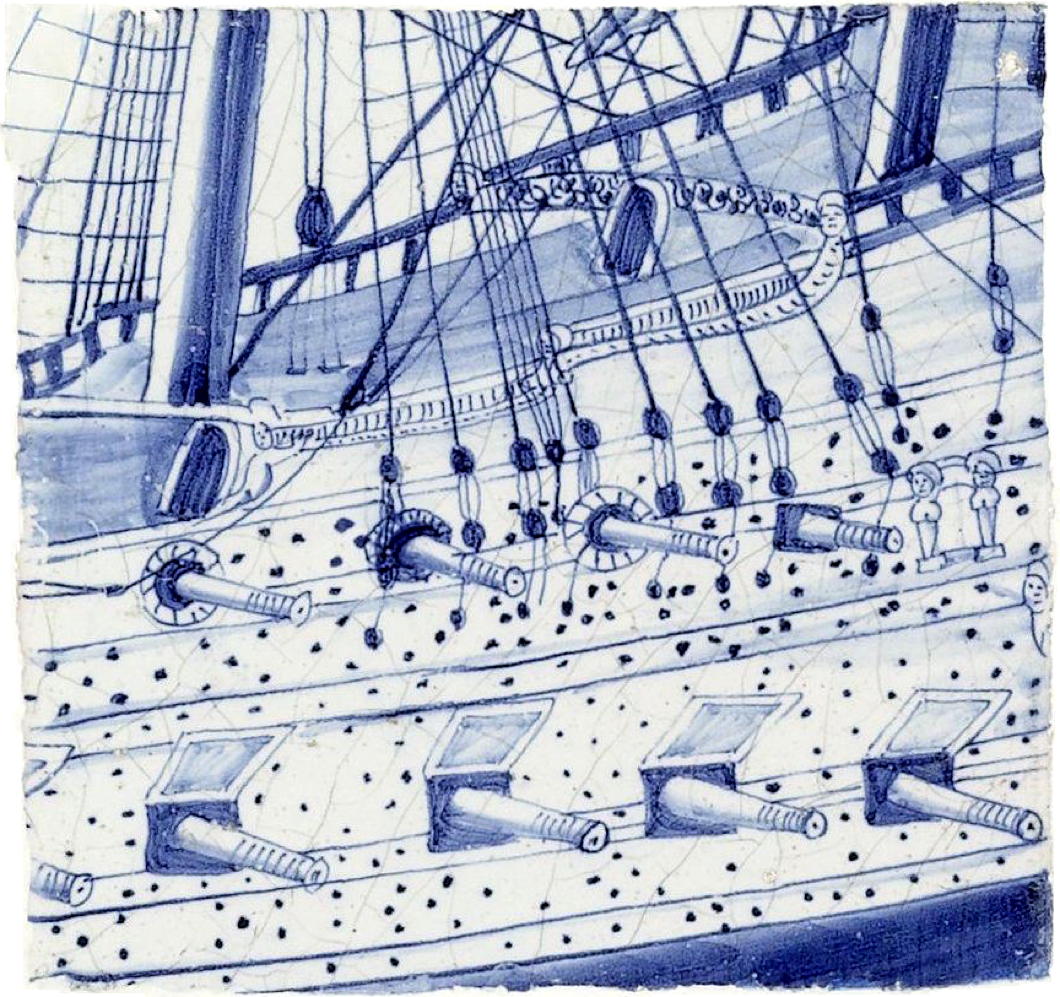

An East Indiaman

English sea-goers and merchants commonly referred to any ship of the Dutch VOC (or of other similar companies) as an ‘East Indiaman’.

Corpus Christi

The Master of James IV of Scotland, Flemish c. 1541; Getty Museum

Safavid Pottery Tile

A seventeenth-century pottery tile from Safavid Persia — from the collection of the late Pierre Le-Tan.

Merton

The ‘House or College of Scholars of Merton in the University of Oxford’ — more commonly called Merton College — is one of the smaller colleges in Oxford, located right next door to lovely little Corpus.

Aside from rendering the architecture well, townscapes from the eighteenth century often give delightful little hints of city life. Michael Rooker (1746–1801) painted this scene of Merton College from its eponymous street in 1771, and the view today is hardly changed at all.

One of my favourite cityscapes is Canaletto’s view of the back end of Downing Street looking towards the old Horse Guards which you can pop into the Tate and see thanks to the generosity of Lord Lloyd-Webber. Incidentally, both scenes depict carpets being hung out for beating.

If you love the capital of the Netherlandosphere I recommended adding to your library Kijk Amsterdam 1700-1800: De mooiste stadsgezichten (‘See Amsterdam 1700-1800: The Most Beautiful Cityscapes’), the well-produced catalogue of the 2017 exhibition of the same name at the Amsterdam City Archives which includes 300 illustrations in full colour.

It’s high time the Museum of Oxford or the Ashmolean — or anyone really — put together a similar exhibition of Oxford cityscapes from the same century.

Incidentally, it was in Merton Field as a teenager that I played my first game of cricket. Who would have guessed then that eighteen years later your humble and obedient scribe would be facing the Vatican on the field of battle in the same sport? (We lost.)

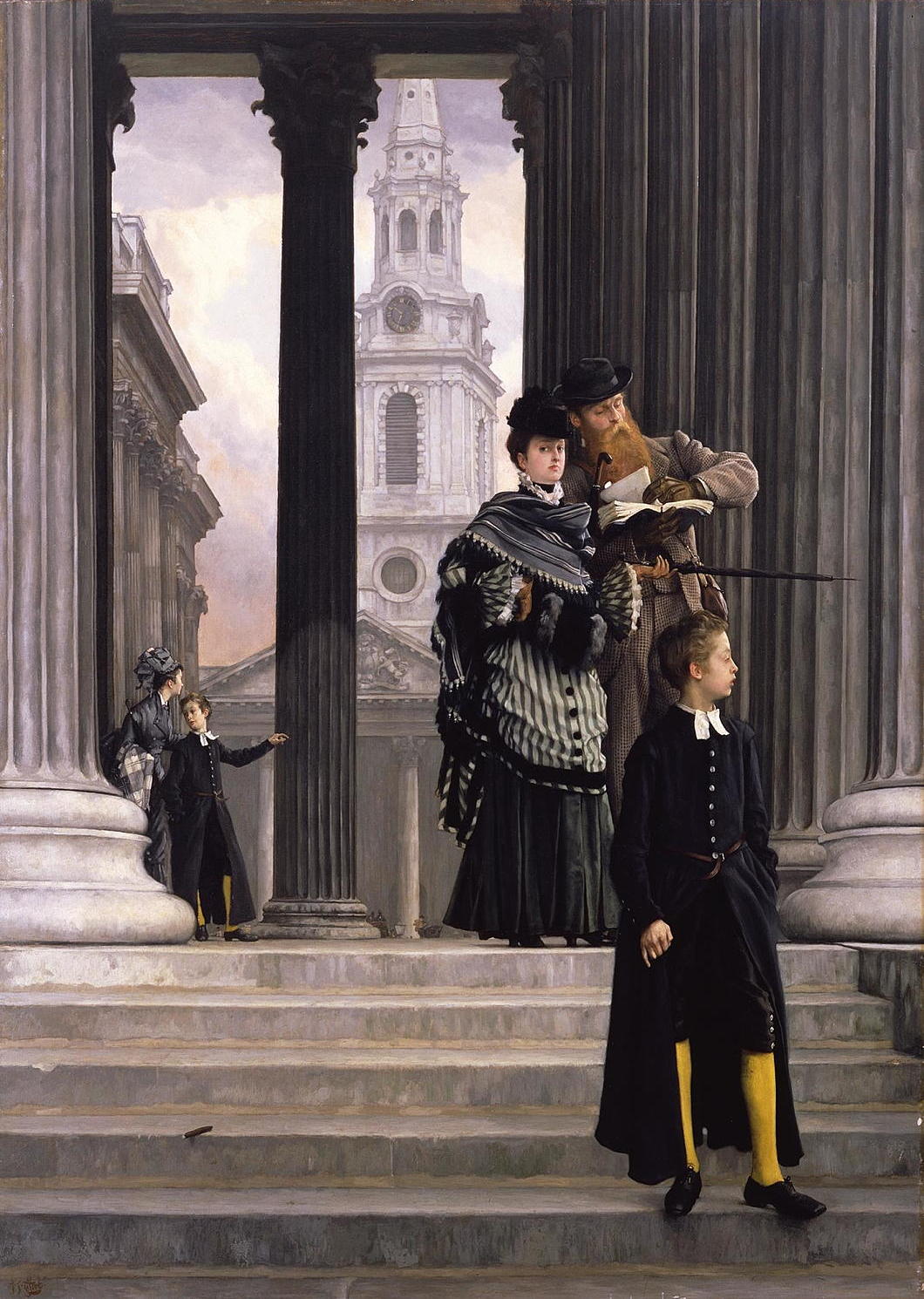

London Visitors

1874, oil on canvas, 63 x 45 in.

Happily, the Tudor-era uniforms are still in use there and are the hallmark of the school to this day.

The visiting couple are obviously in from the provinces, and the woman gazes daringly at the viewer.

I wonder if the cigar on the steps was left for a moment by the artist as he dashed to take this snapshot.

The Galloway Cross

What could be better than a hoard — and a Kircudbrightshire hoard at that? Sometime during the tenth century, a gentleman decided to deposit an interesting array of objects in Galloway only for them to be rediscovered by a metal detectorist in 2014.

Thus have come to us the Galloway Hoard, a collection of objects the most important of which is this pectoral cross made of silver and decorated with symbols of the four evangelists: the eagle of John, the ox of Luke, the angel of Matthew, and the lion of Mark.

As the hoard was buried when Kircudbrightshire was part of Northumbria — before the area became Scottish — the art has been identified as Anglo-Saxon from the age of the Vikings. My theory is an expert thief was at work, nicking precious objects from hapless victims — an armband gives the name of one poor Egbert in runes.

“The pectoral cross, with its subtle decoration of evangelist symbols and foliage, glittering gold and black inlays, and its delicately coiled chain, is an outstanding example of the Anglo-Saxon goldsmith’s art,” Dr Leslie Webster, an expert, said. “It was made in Northumbria in the later ninth century for a high-ranking cleric, as the distinctive form of the cross suggests.”

The Galloway Cross, before cleaning and conservation

All treasure found in Scotland must be reported to the Queen’s and Lord Treasurer’s Remembrancer who in 2017 determined the hoard’s value at £1.8 million. Scots law allows the discoverer to keep the full value of the hoard if there is no owner, though as it was found on glebelands belonging to the Church of Scotland that body’s General Trustees demanded a cut as well.

The objects themselves have found a home in the National Museum of Scotland who will be exhibiting them from February until May when they will go on tour to Aberdeen and Dundee.

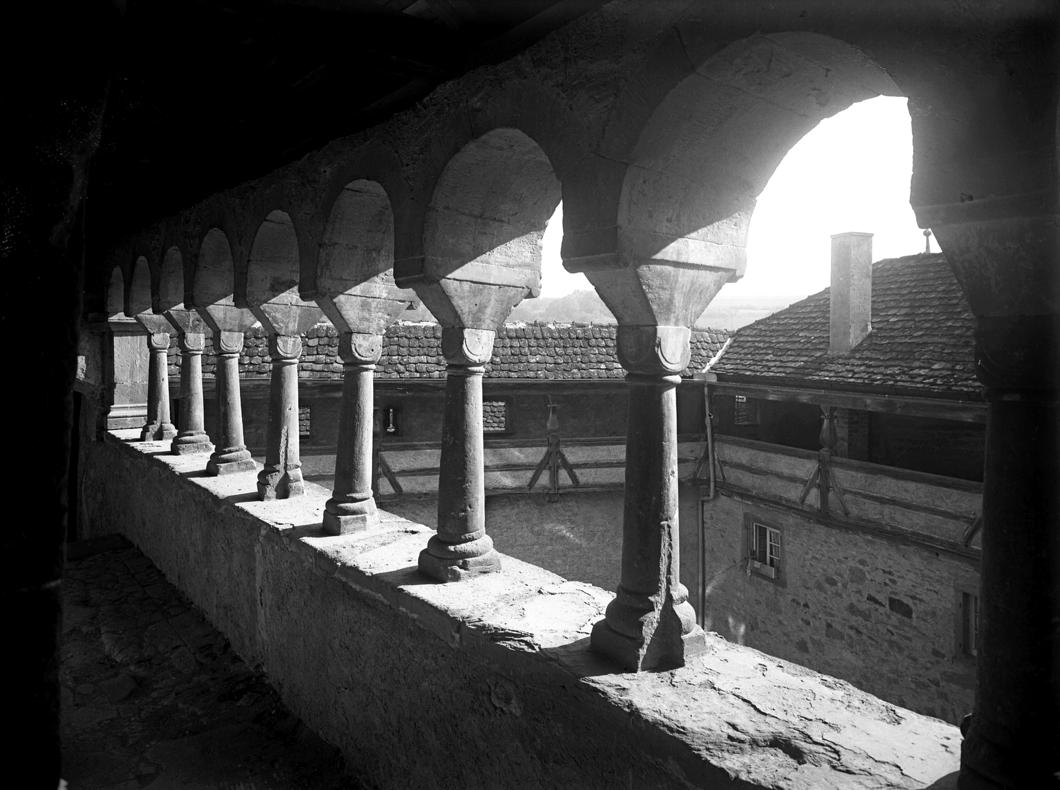

Großcomburg

While the old basilica was demolished in the 1700s and replaced with a baroque creation there is still plenty of Romanesque abiding at Großcomburg in Swabia. The monastery was founded in 1078 and the original three-aisled, double-choired church was consecrated a decade later. Its community experienced many ups and downs before the Protestant Duke of Württemberg, Frederick III, decided to suppress the abbey and secularise it. Many of its treasures were melted down and its library transferred to the ducal one in Stuttgart where its mediæval manuscripts remain today.

From 1817 until 1909 the abbey buildings were occupied by a corps of honourable invalids, a uniformed group of old and wounded soldiers who made their home at Comburg.

In 1926 one of the first progressive schools in Württemberg was established there, only to be closed in 1936. Under the National Socialists it went through a variety of uses: a building trades school, a Hitler Youth camp, a labour service depot, and prisoner of war camp.

With the war’s end it housed displaced persons and liberated forced-labourers until it became a state teacher training college in 1947, which it remains to this day.

Black-and-white photography is particular suitable for capturing the beauty and the mystery of the Romanesque.

These images of Großcomburg are by Helga Schmidt-Glaßner, who was responsible for many volumes of art and architectural photography in the decades after the war.

Mauritz de Haas

Stormcloud and moonlight — these were the preferred settings of the marine paintings of Mauritz Frederik Hendrik de Haas.

Born in Rotterdam in 1832, he studied at the academy there as well as in the Hague under Bosboom and Meijer.

At the age of twenty-five, de Haas accepted an artist’s commission in the Dutch Royal Navy, carrying on for two years until the Rhenish-Sephardic financier August Belmont (a former American ambassador to the Netherlands) persuaded him to come to America in 1859.

By 1867 de Haas was an academician of the National Academy and a founding member of the American Society of Painters in Water Colors.

His brother, Willem Frederik de Haas, was also a marine painter, but Mauritz’s scenes are much more atmospheric — especially as one moves from day through dusk and into the light of the moon.

oil on canvas, 17 in. x 30 in.

Doom in Bloom

Such paintings were widespread in Catholic England where they served as a vital reminder to the faithful worshipping below of not just the torments of Hell but also the joys of Heaven. In the aftermath of the Protestant revolt, however, such vivid imagery was frowned upon, and the Salisbury Doom was painted over with limewash in 1593. Christ in Majesty was replaced by the royal arms of the usurper queen, Elizabeth I.

It was then forgotten about til its rediscovery in 1819 when hints of colour were discovered behind the royal arms. The limewash was removed, the remnants of the painting were revealed, recorded by a local artist, and then covered over yet again in white. Finally in 1881 the Doom was revealed to the world and subject to a Victorian attempt at restoration with mixed results.

Work on the church’s ceiling in the 1990s allowed experts to better examine the Doom which determined that, while there was a bit of fading, dirt was hanging loosely to the painting and it would be ripe for restoration. It has only been more recently, however, that money has been raised to restore the Doom.

There are other glories in this church yet to be restored, about which more information can be found on the parish’s website.

The Salisbury Doom before restoration (above) and after (below).

Lady Day

Today is Lady Day, the Feast of the Annunciation when the Archangel Gabriel appeared to the Blessed Virgin Mary and announced that she would conceive and bear the child Jesus.

The angelic salutation – “Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee… Blessed art thou amongst women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus” – forms the basis of the Ave Maria, one of the most widely uttered prayers in Christendom.

Traditionally this has been one of the greatest of devotions to the Virgin amongst the English, which is why there are so many pubs across England named ‘The Salutation’.

For centuries in England and Scotland (as well as elsewhere), Lady Day was the first day of the calendar year. Scotland moved this to 1 January in 1600 and England did likewise in 1750.

Nonetheless, the English tax year is still based on this date as it commences on 6 April, which is the Annunciation plus twelve days to mark the difference between the old Julian calendar and the modern Gregorian one.

In the realms of fiction, 25 March is the day Tolkien chose for when Frodo destroyed the Ring in Mount Doom, securing the fall of Sauron – with obvious parallels to Christ’s Incarnation securing the defeat of Satan.

This stained glass roundel above is not English, however, but from the Southern Netherlands around 1500-1510.

Elsewhere, A Clerk of Oxford has a good section on the Annunciation.

Sir John Soane

Sir John Soane still looms over the intervening centuries of architecture and design in Great Britain, but I’ve never actually known what he looked like. Apparently this is him, in an 1804 portrait by William Owen.

Everyone’s been to his house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, but Pitzhanger Manor, his place in the country (though Ealing hardly seems rural today) was recently reopened after serious conservation works ongoing since 2015.

Hope to pay it a visit soon.

Secret Splendor

by Andrew Cusack (Weekly Standard, 13 September 2010)

Paintings for the Catholic Church in the Dutch Republic

by Xander van Eck

Waanders, 368 pp., $100

This book is the first major overview and exploration of the art of the clandestine Roman Catholic churches in the Netherlands. It is not a study of paintings so much as a history in which art is like the evidence in a detective story, or perhaps even the characters in a play. It might seem extraordinary that there was a place for large-scale Catholic art during the Dutch Republic: Pre-Reformation churches had been confiscated and were being used for Calvinist services, while priests offered the Mass secretly in makeshift accommodations. Eventually a bargain between Dutch Catholics and the civil authorities emerged, trading Catholic nonprovocation in exchange for private toleration of the practice of the faith. Catholics began to purchase properties which, for all outward appearances, maintained the look of ordinary residences but whose interiors were transformed into resplendent chapels and churches.

Xander van Eck provides verbal portraits (often accompanied by contemporaneous painted ones) of several of the important clerics of the Dutch church during this period: Sasbout Vosmeer, the Delft priest influenced by St. Charles Borromeo; Philippus Rovenus, the vicar-apostolic who placed greater emphasis on clandestine parishes having specially dedicated churches, even while they kept an outward unecclesiastical appearance; and Leonardus Marius, the priest who promoted devotion to the 14th-century Eucharistic “Miracle of Amsterdam.” Marius was of such prominence that, after his death, shopkeepers rented out places on their awnings for punters to view his funeral procession. Van Eck includes a handful of amusing asides, such as the expulsion of the Jesuits from the Netherlands as a result of their constant discord with the secular clergy. Mass continued to be offered at the Jesuit church of De Krijtberg in Amsterdam “in the profoundest secrecy” — thus creating a clandestine church within a clandestine church!

The role of the clergy in sustaining the Dutch Church is unsurprising, but it is instructive to learn how instrumental laity were to keeping alive the light of Catholic faith in the Netherlands at the time. Clandestine churches relied on the generosity of Catholic families. Prominent families often provided their own kin as consecrated virgins who brought large dowries into the church, or as priests with suitable inheritances to maintain or endow clandestine parishes. The clandestine church of ’t Hart in Amsterdam, built by the merchant Jan Hartman for his son studying for the priesthood, is still open today as the Amstelkring Museum and Chapel of “Our Lord in the Attic.”

While van Eck explores the extent to which Dutch art from the period followed European norms, an emphasis on the particularity of the art of the clandestine church is to be expected. The sheer volume of art produced during this period — for just three Amsterdam churches alone there were 16 altarpieces — is partly explained by the phenomenon of “rotating altarpieces.” The paintings above the altar would be changed according to the feast or season — a practice sometimes seen in Flanders or parts of Germany but never nearly so widespread as in the Netherlands proper.

Constrained as clandestine churches were on the narrow plots typical of Dutch cities, there was no room for side chapels that might include the large funerary monuments prominent families would construct. This left altarpieces as the most convenient way for munificent Catholics to provide art for their churches: Rotating the altarpieces provided a handy way of displaying numerous commissions rather than just the donation of whoever had been generous most recently, and the themes of these commissions tended to vary in appropriateness to different feasts and seasons.

Some found fault with this method: Jean-Baptiste Descamps, visiting Antwerp in 1769, complained that the most interesting altarpieces were not permanently displayed and were more likely to be damaged in the process of being moved so often.

While the accomplishment and ingenuity of Dutch Catholics in keeping their faith during the Republic was striking, the ill-defined administrative structure of the persecuted church allowed conflicts between clerics to thrive, and doctrinal disputes emerged and festered. The disputes over Jansenism that swept over France and the Netherlands, for example, only exacerbated the administrative problems of the clandestine church. Like their Calvinist compatriots, the Jansenists tended to frown on indulgences, the veneration of saints, recital of the rosary, and private acts of worship, putting greater emphasis on the Scriptures and a more rigorous asceticism. As van Eck points out, this difference in emphasis was not exclusive to the Jansenists, but their novelty (and their heresy) was in preaching the exclusivity of their approach above all others.

Numerous vicars-apostolic had written to Rome arguing for the re-establishment of the episcopacy in the Netherlands to solve the disputes over authority, but their appeals fell on deaf ears. In 1723 a large portion of the Jansenist clergy reinstituted the episcopacy by electing an archbishop of Utrecht from their number — and were subsequently excommunicated, splitting the clandestine church and its clergy in two. (This excommunicated rump united with the opponents of papal infallibility in the following century to form a body that still calls itself the Old Catholic Church.)

When one looks at all this glorious art, not to mention the lives and pious ingenuity of the persecuted, it’s difficult not to feel a little poorer, considering the fruits of our churches in an ostensibly free era. Why does the church today commission painters who are either mediocre or trendy — or both? Artists like Hans Laagland and Leonard Porter show that good art — good liturgical art, even — is possible today, but commissions from the church for traditional artists are sadly few.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

- Waarburg October 2, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories