Rhodesia

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The Dutch in Rhodesia

…and why they stayed there.

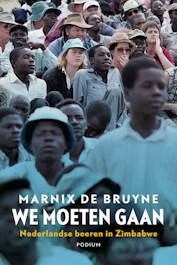

Journalist Marnix de Bruyne has shed new light on the post-war wave of Dutch immigration to Rhodesia with his new book, We moeten gaan. Nederlandse boeren in Zimbabwe (‘We Must Go: Dutch Farmers in Zimbabwe’).

Journalist Marnix de Bruyne has shed new light on the post-war wave of Dutch immigration to Rhodesia with his new book, We moeten gaan. Nederlandse boeren in Zimbabwe (‘We Must Go: Dutch Farmers in Zimbabwe’).

Why did so many people emigrate from the Netherlands in the fifties? Why did hundreds of them choose to settle in what was then called Rhodesia, today’s Zimbabwe? And why did so many of them stay after 1965, when the country was led by a white-minority regime, faced an international boycott and was engulfed in a bloody guerrilla war?

De Bruyne attempted to answer these questions through a recent seminar at Leiden University’s African Studies Centre. The university has rather handily made a recording of the seminar available online.

Daar’s ook ’n interview (in Nederlands) met Mnr de Bruyne in Mare, die koerant van die Universiteit Leiden.

(Dave: hierdie post is vir jy!)

The Prime Minister & His Wife

The Rt Hon Ian Douglas Smith & Mrs Smith, at home in Salisbury, Rhodesia.

Theodore Dalrymple on Rhodesia

The young black doctors who earned the same salary as we whites could not achieve the same standard of living for a very simple reason: they had an immense number of social obligations to fulfill. They were expected to provide for an ever expanding circle of family members (some of whom may have invested in their education) and people from their village, tribe and province. An income that allowed a white to live like a lord because of a lack of such obligations scarcely raised a black above the level of his family. […]

It is easy to see why a civil service, controlled and manned in its upper reaches by whites could remain efficient and uncorrupt but could not long do so when manned by Africans who were suppose to follow the same rules and procedures. The same is true, of course, of every other administrative activity, public or private. The thick network of social obligations explains why, while it would have been out of the question to bribe most Rhodesian bureaucrats, yet in only a few years it would have been out of the question not to try to bribe most Zimbabwean ones, whose relatives would have condemned them for failing to obtain on their behalf all the advantages their official opportunities might provide. Thus do they very same tasks in the very same offices carried out by people of different cultural and social backgrounds result in very different outcomes.

Viewed in this light, African nationalism was a struggle for power and privilege as it was for freedom, though it co-opted the language of freedom for obvious political advantage.

The Mandarins and the Masses

“We Live in Hope”

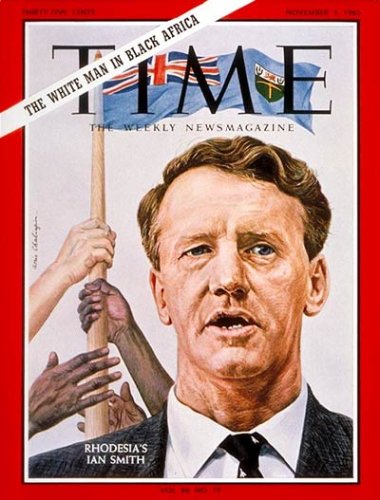

Ian Smith, the Grand Old Man of Africa, Speaks

Here is an interesting nine-minute-long clip from a documentary on Ian Smith, the former Prime Minister of Rhodesia, featuring the Hon. Mr. Smith himself, now eighty-eight years of age, as well as Kathy Olds, a landowner, and Ernest Mtunzi, a former aide to ZAPU leader Joshua Nkomo.

“What we believed in was responsible majority rule, as opposed to irresponsible majority rule and I stand by that,” Mr. Smith tells the interviewer. “I think it is important that before you give a person the vote you ensure that his roots go down, that he’s part of the whole structure of the country.”

“Smith is an African,” Ernest Mtunzi says. “He understands the African mentality. […] Smith was being realistic. If you give people something before they’re ready, they’re going to mess it up. And that has happened.”

“Africa is a continent which is subject to a great deal of friction and argument and change,” Smith concludes. “That’s part of the world generally but more so Africa than anywhere else. So because of that we live in hope. We think that the people they in the end will say we’ve had enough.”

“In the interest of our people and of other people this part of the world, let’s work together. […] Let’s just accept that we are all part of Africa, all part of the world. Let’s all work together and the more we can get people to accept that philosophy I think the greater the hope for the whole world.”

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

- American Exuberant February 10, 2025

- Crux Alba Journal Launch February 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories