Germany

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The Freiherr of Finance

Germany’s new finance minister, Freiherr zu Guttenberg & his wife, Freifrau Stephanie.

Unmentioned by this editorial is that Baron zu Guttenberg’s grandfather (his mother’s father) was the late German winemaker & Croatian politician the Count of Vukovar. From the Count, Baron zu Guttenberg is descended from the noble house of Eltz, who are responsible for one of my favourite castles in the whole world, Burg Eltz, which once graced the 500-deutschmark note.

At the ripe age of 70, the Count of Vukovar took up arms in defence of the town of Vukovar during the Yugoslav Wars of 1991. The Count was elected to the Croatian parliament the following year as an independent, and served in that body until 1999, when he retired from politics. Nonetheless, the Croatian parliament persuaded him to accept honourary membership of parliament in his own right, in which role he continued until his death in 2006.

The Baron’s wife, meanwhile, is Stephanie, Countess of Bismarck-Schönhausen, great-great-granddaughter of the “Iron Chancellor”, Otto von Bismarck. A portent of this economics minister’s future?

The Goerke House, Lüderitz

THE FAMILIAR PHRASE has a person in difficult circumstances being “between a rock and a hard place”. The Namibian town of Lüderitz is stuck between the dry sands of the desert and salt water of the South Atlantic — this is the only country whose drinking water is 100% recycled. Life in this almost-pleasant German colonial outpost on the most inhospitable coast in the world has always been something of a difficulty, but the allure of diamonds has at least made it profitable. One such adventurer who came from afar and made his fortune in this outer limit of the Teutonic domains was one Hans Goerke. (more…)

S.R.E. & S.R.I.

Left, a prince of the Holy Roman Church and right, a prince of the Holy Roman Empire.

Credit: I think this is one of Zygmunt’s photos.

Count von Stauffenberg: “We Live in a Society of Lemmings”

Count Franz Ludwig von Stauffenberg, the third son of Hitler’s would-be assassin Count Claus von Stauffenberg and brother to Gen. Berthold von Stauffenberg, recently spoke to the German magazine FOCUS about Germany’s ratification of the Lisbon Treaty. Stauffenberg, a father of four and grandfather of eight, has spent his life as an attorney and a politician for the Bavarian Christian Social Union party, serving in the Bundestag from 1976 to 1987 and as a Member of the European Parliament from 1984 to 1992.

FOCUS asked the Count about his participation in the German court challenge against the Lisbon Treaty.

“I see the way to [the Constitutional Court] as a last resort,” the Count said, “and had hoped that we could compel a re-think through an ordinary democratic manner, through argument, debate, and public pressure. This has totally failed. I’m not anti-European; I was long enough a CSU Member of the European Parliament. This Europe is no longer compatible with the basic structures of a democratic legal state.”

FOCUS: Has your case something to do with your experience as the son of the resistance fighter Count von Stauffenberg?

“No. My father expected that his children would … stand on their own as a man or woman. I didn’t go into politics from devout worship of my father, but because of the unsuccessful paths of my peers from the generation of 1968.”

FOCUS: Your action comes late. Why have you waited so long?

“In Brussels, there was no sudden seizure of power, but a systematic, persistent development, in which the Bundestag deputies, constantly obedient and even docile, incapacitated themselves. They see themselves as a reserve team for higher office rather than in their actual role as inspectors to reflect, as a counter force on equal footing.”

FOCUS: How can it be that so few see a risk in the Lisbon Treaty, and the rest should be so beaten with blindness?

“In Germany, almost no one wanted to hear concerns. We live in a society of lemmings.”

Link: Graf Stauffenberg: “Wir leben in einer Gesellschaft von Lemmingen” (In German)

Debating Stauffenberg

The recent release of the Hollywood film “Valkyrie” has brought the July ’44 plot back into the limelight. Much debate has focussed on the central figure of Count von Stauffenberg, especially the motivation and inspiration for his attempt to overthrow the Nazi regime. Writing in Süddeutsche Zeitung, Richard Evans (Regius Professor of Modern History at Cambridge) asks “Why did Stauffenberg plant the bomb?” Prof. Evans argues that the Count’s contempt for liberalism combined with his (Stefan George-influenced) romantic nostalgia « make him ill-fitted to serve as a model for the conduct and ideas of future generations » .

A week later, the Süddeutsche Zeitung published “Unmasking the July 20 plot“, a response to Evans by Karl Heinz Bohrer, the publisher of Merkur and a visiting professor at Stanford. Bohrer counters Evans on two fronts. « Firstly Evans’s lesson consisted of historical half truths, contradictory theses and slanderous allusions to Stauffenberg’s character; and secondly, such distortions differ very little from the view held by West German intelligentsia regarding the events of July 20th 1944 and the conspirators who were, for the most part, of aristocratic Prussian stock. … For a proper understanding of the how the plot against Hitler of 1944 is seen and judged today, one should bear in mind that today’s horizon has shifted. »

« There is no question that like Ernst Jünger and Gottfried Benn, Stauffenberg’s first spiritual influence, Stefan George, entertained pre-fascist fantasies. And there is also no question that the young Stauffenberg’s reverence for the medieval ‘reich’ was reactionary – in a similar vein to Novalis’s ideas in ‘Die Christenheit oder Europa’. But what does that mean? Neither of them had political ideas that could in any way have served as a model for democratic European societies in the second half of the twentieth century. But to fundamentalise this tautological insight to effectively deny the conspirators any moral or cultural relevance is blinkered and constitutes intellectual bigotry. George, Jünger and Benn’s pre-fascist fantasies contained important modernist symbols which mean they cannot be judged by political moralist criteria, alone. The same goes for Stauffenberg and his friends who – in a different way to the “idealistic” Scholl siblings and their circle – represented a calibre of ethics, character and culture class of which today’s politicians and other bureaucratic elites can only dream. »

In that same week, Bernard-Henri Lévy — the omnipresent French man of letters — waddled into the debate with “Beyond the war hero” in the pages of Le Point. BHL proclaims the release of “Valkyrie” is unquestionably good, for it is inherently good for the world to honour its heroes. « Riveting as it is however, this film poses certain questions that are too complex and too delicate to be resolved solely within the logic of the Hollywood film industry. »

In a moment of pure irony, Lévy attacks the lack of accuracy in the film while making a gross historical error himself. The philosopher asks whether « raising someone to hero status does not always happen, alas, to the detriment of precision, nuance and history itself. The film shows Stauffenberg’s integrity very well. It shows his courage, the nobility of his views, his firmness of spirit. But what does it tell us of his thoughts? What does it teach us about why he enthusiastically joined the Nazi Party in 1933? » In actual fact, while Stauffenberg’s family members were concerned that he was “turning brown” the Count never joined the Nazi Party; not in 1933, not ever.

In a sense, Lévy has answered his own question in that Stauffenberg’s elevation has apparently taken place to the detriment of precision and history in that Lévy is apparently unaware of quite central historical facts of the case.

Previously: Stauffenberg

Berlin to build ersatz Stadtschloß

Afraid of celebrating glorious past, a horrible future is created instead

Fresh from the glories of Dresden’s rebuilt Lutheran Frauenkirche, the city fathers of Berlin have decided to reconstruct the old Stadtschloß (“City Palace”) at the heart of the German capital, only not quite. Largely ignored by the anti-monarchist Nazis, the original Stadtschloß was damaged by Allied bombing and by shelling during the Battle of Berlin before the Communist government of East Germany demolished it entirely and built the horrendously ugly Palast der Republik (housing the Soviet satellite’s faux parliament) on the site. The Communist monstrosity has finally been demolished, but the authorities decided that, rather than restore the beautiful royal palace that once stood on the site, they will instead merely replicate three of the old structure’s façades, leaving one of the façades and most of the interior in a modern style.

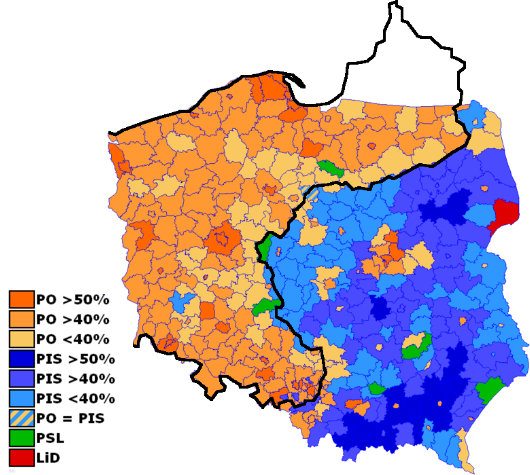

‘German’ Poland vs. ‘Russian’ Poland

A curiosity of the 2007 Polish parliamentary election

THIS MAP displaying the results of the 2007 general election for the Polish parliament is overlaid with an outline of the nineteenth-century border between the German and Russian empires.

The areas formerly ruled by the German Kaiser tend to back the right-wing liberal Platforma Obywatelska (“Civic Platform”) party, while those formerly ruled by the Tsar tend to support the conservative Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (“Law and Justice”) party.

The green represents the centrist-agrarian Polish People’s Party, while the dark red represents the already-defunct “Left and Democrats” coalition.

Source: Strange Maps

Sorb Serf Story Shown on Silver Screen

Otfried Preußler’s retelling of old Wendish legend hits German cinemas

Follow your dreams! It may sound like a Hollywood cliché, but what’s a fourteen-year-old orphaned Sorb peasant to do? Currently showing in German cinemas, “Krabat” is the first film version of Otfried Preußler’s 1971 novel of an old Sorbian tale whose eponymous protagonist is a beggar boy in the eastern Saxony of the early 1700s. Krabat is plagued by dreams of an old watermill outside the tiny hamlet of Schwarzkollm, which seems to be operational though farmers never bring grain to be milled.

NRC, among others, gets it right

The Netherlands’ premier broadsheet has gone partly English online

The moderate liberal Dutch broadsheet NRC Handelsblad is the latest of a series of European periodicals looking for a more international readership by translating part of their content into English for distribution on the world wide web. “NRC International” is partnered with the German weekly magazine Der Spiegel, itself a pioneer in featuring English content in an “international” section of its website. Aside from NRC and Der Spiegel, other news outlets now featuring web-only English-language content are Germany’s Die Welt and Hungary’s Heti Világgazdaság, while Eurozine features translated and original content from a broad spectrum of continental reviews and journals. Sadly, Sign and Sight recently had to reduce their “From the Feuilletons” — looking at the culture pages of German-language newspapers — from a daily to a weekly feature. Sign and Sight also features a weekly “Magazine Roundup” doing the rounds of a wide variety of European, Asian, and American magazines.

The move comes as print newspapers of the conventional variety across Europe and America are losing circulation. Some Manhattan newsstands have seen takers for the Sunday New York Times fall by as much as 80% in the past few years. The New York Times and Wall Street Journal both recently narrowed their page width in a move to save paper costs; the change, however, also means less room for advertising and a more ungainly appearance.

South Africa’s Herald, meanwhile, has bucked the gloomy trend and increased its readership by 14.5% in the past year. The Herald, the Eastern and Southern Cape’s regional broadsheet, attributes its success to a visual redesign and reorienting content to encourage readers to link up with the newspaper’s website. South Africa is also home to The Times (not to be confused with the older Cape Times), a new upmarket broadsheet newspaper launched as a daily extension of the century-old Sunday Times. The weekday Times was started a year ago and its circulation since just June has seen a 10.4% increase.

A major problem for the industry is that formerly high-end newspapers have driven down the quality of their product to a suicidal extent over the past decades. The middle market, for better or worse, is dead, and publishers have three alternatives to this disappearing sector: 1) go lowest-common-denominator — as The Times of London has done, with only moderate success; 2) go up-market — The Times and Sunday Times of South Africa have proved worthwile; or 3) go niche — the New York Observer is still in business after two decades of aiming towards Manhattan’s yuppie community.

Whichever path taken, integrating print and web operations is vital for the survival of print newspapers and other “dead tree” media. That European newspapers are providing at least part of their content in English is helpful in keeping up with events and ideas in countries like Germany, the Netherlands, and Hungary as our native English-language media are tightening their belts and cutting foreign correspondents and coverage. I hope more non-English papers follow this trend and help to permanentize it.

‘The man who walked’

The Daily Telegraph — 6 September 2008

At 18 he left home to walk the length of Europe; at 25, as an SOE agent, he kidnapped the German commander of Crete; now at 93, Patrick Leigh Fermor, arguably the greatest living travel writer, is publishing the nearest he may come to an autobiography – and finally learning to type. William Dalrymple meets him at home in Greece

‘You’ve got to bellow a bit,’ Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor said, inclining his face in my direction, and cupping his ear. ‘He’s become an economist? Well, thank God for that. I thought you said he’d become a Communist.’

He took a swig of retsina and returned to his lemon chicken.

‘I’m deaf,’ he continued. ‘That’s the awful truth. That’s why I’m leaning towards you in this rather eerie fashion. I do have a hearing aid, but when I go swimming I always forget about it until I’m two strokes out, and then it starts singing at me. I get out and suck it, and with luck all is well. But both of them have gone now, and that’s one reason why I am off to London next week. Glasses, too. Running out of those very quickly. Occasionally, the one that is lost is found, but their numbers slowly diminish…’

He trailed off. ‘The amount that can go wrong at this age – you’ve no idea. This year I’ve acquired something called tunnel vision. Very odd, and sometimes quite interesting. When I look at someone I can see four eyes, one of them huge and stuck to the side of the mouth. Everyone starts looking a bit like a Picasso painting.’

He paused and considered for a moment, as if confronted by the condition for the first time. ‘And, to be honest, my memory is not in very good shape either. Anything like a date or a proper name just takes wing, and quite often never comes back. Winston Churchill – couldn’t remember his name last week.

‘Even swimming is a bit of a trial now,’ he continued, ‘thanks to this bloody clock thing they’ve put in me – what d’they call it? A pacemaker. It doesn’t mind the swimming. But it doesn’t like the steps on the way down. Terrific nuisance.’

We were sitting eating supper in the moonlight in the arcaded L-shaped cloister that forms the core of Leigh Fermor’s beautiful house in Mani in southern Greece. Since the death of his beloved wife Joan in 2003, Leigh Fermor, known to everyone as Leigh Fermor, has lived here alone in his own Elysium with only an ever-growing clowder of darting, mewing, paw-licking cats for company. He is cooked for and looked after by his housekeeper, Elpida, the daughter of the inn-keeper who was his original landlord when he came to Mani for the first time in 1962.

It is the most perfect writer’s house imaginable, designed and partially built by Leigh Fermor himself in an old olive grove overlooking a secluded Mediterranean bay. It is easy to see why, despite growing visibly frailer, he would never want to leave. Buttressed by the old retaining walls of the olive terraces, the whitewashed rooms are cool and airy and lined with books; old copies of the Times Literary Supplement and the New York Review of Books lie scattered around on tables between Attic vases, Indian sculptures and bottles of local ouzo.

A study filled with reference books and old photographs lies across a shady courtyard. There are cicadas grinding in the cypresses, and a wonderful view of the peaks of the Taygetus falling down to the blue waters of the Aegean, which are so clear it is said that in some places you can still see the wrecks of Ottoman galleys lying on the seabed far below.

There is a warm smell of wild rosemary and cypress resin in the air; and from below comes the crash of the sea on the pebbles of the foreshore. Yet there is something unmistakably melancholy in the air: a great traveller even partially immobilised is as sad a sight as an artist with failing vision or a composer grown hard of hearing.

I had driven down from Athens that morning, through slopes of olives charred and blackened by last year’s forest fires. I arrived at Kardamyli late in the evening. Although the area is now almost metropolitan in feel compared to what it was when Leigh Fermor moved here in the 1960s (at that time he had to move the honey-coloured Taygetus stone for his house to its site by mule as there was no road) it still feels wonderfully remote and almost untouched by the modern world.

When Leigh Fermor first arrived in Mani in 1962 he was known principally as a dashing commando. At the age of 25, as a young agent of Special Operations Executive (SOE), he had kidnapped the German commander in Crete, General Kreipe, and returned home to a Distinguished Service Order and movie version of his exploits, Ill Met by Moonlight (1957) with Dirk Bogarde playing him as a handsome black-shirted guerrilla.

It was in this house that Leigh Fermor made the startling transformation – unique in his generation – from war hero to literary genius. To meet, Leigh Fermor may still have the speech patterns and formal manners of a British officer of a previous generation; but on the page he is a soaring prose virtuoso with hardly a single living equal.

It was here in the isolation and beauty of Kardamyli that Leigh Fermor developed his sublime prose style, and here that he wrote most of the books that have made him widely regarded as the world’s greatest travel writer, as well as arguably our finest living prose-poet. While his densely literary and cadent prose style is beyond imitation, his books have become sacred texts for several generations of British writers of non-fiction, including Bruce Chatwin, Colin Thubron, Philip Marsden, Nicholas Crane and Rory Stewart, all of whom have been inspired by the persona he created of the bookish wanderer: the footloose scholar in the wilds, scrambling through remote mountains, a knapsack full of books on his shoulder.

Germany carved amongst her neighbours

What is this cartographic madness? Hanover part of the Netherlands? Kassel ruled by France? Nuremburg part of a Bohemia that reaches to the Frankfurt suburbs? Hamburg in Denmark? Regensburg on the Austro-Czech border? I came across the company Kalimedia in an article from Die Zeit a month or two ago and discovered their map of a Europe without a Germany. Believe it or not, there were plans of one sort or another to achieve similar results at the end of the Second World War. The major plan for the dissection of Germany was merely a creation of Nazi propaganda, and while the vaguely similar Morgenthau Plan did exist, it was soon shelved once its impracticality became obvious.

The Bakker-Schut Plan, meanwhile, was a Dutch proposal for the annexation of several German towns, and perhaps even a number of German cities. German natives would be expelled, except for those who spoke the Low Franconian dialect, who would be forcibly dutchified. They even came up with a list of new Dutch names for German cities: c.f. the post at Strange Maps on “Eastland, Our Land: Dutch Dreams of Expansion at Germany’s Expense”.

Le monde diplomatique

The German edition of Le monde diplomatique underwent a complete overhaul not too long ago. Unlike the main French edition of Le monde diplo, which exhibits the exact style of a French newspaper of mediocre design circa 1996, the German edition now exudes a certain calm and composed modernity. The redesign is the work of the German typographer and designer Erik Spiekermann, whom the Royal Society have named a Royal Designer for Industry (entitling him to an HonRDI after his name; only “hon” because he is not a British subject). Mr. Spiekermann was responsible for the much-lauded redesign of The Economist, the magazine you read when the airport lounge doesn’t have a copy of The Spectator.

Amidst pickelhaubes resplendent

The Chancellor of Germany is seen here worriedly admiring the pickelhaubed cavalry on her state visit to Colombia. Such elements of tradition, widespread in South America, are unofficially but totally banned in Germany.

How a newspaper should look

The Sunday edition of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung has always been a handsome newspaper. I admired its appearance so much that it provided much of the inspiration for the look of the Mitre during my editorship of that august publication. The weekday FAZ was famously reactionary in forbidding the appearance of photographs or any colour on the front page, so the Sonntagszeitung was viewed as an opportunity to be a bit more colourful and a little more free, but still within a solid traditional design.

It saddened me to learn that the Monday-through-Thursday FAZ has given in to the Spirit of the Age and now allows not only colour on its front page but photographs there as well. It now looks like a fairly conventional German newspaper, rather than the king of German dailies.

I will miss the old black-and-white FAZ because for me it brings back memories of visits to Dr. Timmerman‘s flat in St Andrews. Sofie and I used to go over to the good professor’s place for German pancakes on Shrove Tuesday (or to listen to his giant old radio, or to simply enjoy good conversation with good wine) and he had a massive pile of Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitungs which I believe he only discarded at the end of the month.

Because the Frankfurter Allgemeine‘s front page is now a little less boring, the world in general is now a little less interesting.

‘Flying High’

[I came across this piece by Taki whilst trawling through the Cusack archives, and I thought now would be the appropriate time to share it.]

By Taki Theodoracopulos (The Spectator, 22 April 2006)

Do any of you remember a film called The Blue Max? It is about a German flying squadron during the first world war. A working-class German soldier manages to escape trench warfare by joining up with lots of aristocratic Prussian flyers who see jousting in the sky as a form of sport, rather than combat. Eager for fame and glory — 20 confirmed kills earns one the ‘Blue Max’, the highest decoration the Fatherland can bestow — the prole shoots down a defenceless British pilot whose gunner is dead. His squadron leader is appalled. ‘This is not warfare,’ he tells the arriviste. ‘It’s murder.’

I know it’s only a film, and a Hollywood one at that, but jousting in the air was a chivalric endeavour back then, with pilots who crash-landed behind enemy lines being treated as honoured guests before being interned for the duration. The man who embodied all the chivalric virtues was, of course, Manfred von Richthofen, whose family had been ennobled by Frederick the Great in the 1740s. When Baron Richthofen became a fighter pilot in the late summer of 1916, it was still only 13 years since the first flight of Orville Wright. The technique of applying air power to warfare was barely understood. One looped-the-loop, and pilots who managed to shoot down enemy aircraft and survive were regarded as heroes and quickly accumulated chestfuls of medals. When the Red Baron (his plane was painted a dark red, hence the nickname) died on 21 April 1918, the Times for 23 April devoted one third of a column to England’s fallen enemy, remarking that ‘all our airmen concede that Richthofen was a great pilot and a fine fighting man’.

By the time of his death, the Red Baron had notched up 80 victories, a record, with the leading French ace, René Fonck, claiming to have shot down 157 German aircraft, but only 75 being confirmed. (Rather French, that.) Needless to say, the mystery surrounding Richthofen’s death added to his legend. No one knows for sure who shot him down, or even if the bullet which killed him came from the ground. The English who found his body treated it with all the ceremony they would have accorded one of their own. An honour guard escorted the corpse to his own lines and British pilots overflew and dipped their wings. Those were the days. Out of 8 million men of his generation who died in that useless war, Richthofen’s is among the few names which will most likely be remembered by the general public on the 200th anniversary of his death.

His brother Lothar and his cousin Wolfram (who bombed Stalingrad 25 years later, and was one of Hitler’s favourites) flew alongside the baron, establishing a tradition for excellence and gallantry in the Luftwaffe. The second world war saw great heroics by German pilots, starting with Hans Ulrich Rudel, with something like 400 Stalin tanks to his credit, Adolf Galland, Erich Hartmann, who shot down 352 Soviet aircraft in the course of 1,500 missions, and Walter Novotny, with 250 Soviet aircraft in fewer than 450 missions.

My favourite is, of course, Prince Heinrich Sayn-Wittgenstein, whose heroics overshadowed the rest, and whose plane was shot down at the very, very end of the war in Schonhausen, the Bismarck home. Wittgenstein had his crew bail out first but was unconscious when he hit the ground. He had been hit while in the cockpit. By the end of the war he had become such an ace and legend he could do what he pleased. He once flew a combat mission with a raincoat over his dinner jacket. A few days before he had been to Hitler’s headquarters to receive the Oak Leaves to his Knight’s Cross. He told the beautiful Missie Vassiltchikov on the telephone, ‘Ich war bei unserem Liebling’ (I have been to see our darling) and added how surprised he was his handgun had not been removed before he entered ‘the Presence’. Heinrich would have loved to have bumped him off, but by then Germany was ruined and the prince died three days later. Hitler had many heroic pilots grounded towards the end, but Wittgenstein, being noble, was kept flying.

Why am I bringing all this up in the year of Our Lord 2006? As I told you last week, while down in Palm Beach, a friend of mine, Richard Johnson, tied the knot with Sessa von Richthofen, and I flew down a group of friends for three days of non-stop celebrations. The couple exchanged vows on an 80-year-old river boat which plies its trade in the inland waterway which crisscrosses Florida. My speech went down great, but then some ghastly paparazzo by the name of Harry Benson went around complaining about it. Never to me, needless to say, otherwise one more kill would have been added to the Richthofen legend.

“Der Rote Baron”

Foreign Film Fictively Frames Favorite Fabled Freiherr

Our cunning cousin, the Hun, has cleverly concealed a card up his hunting-jacket sleeve. Just when you thought the continual winging by hand-wringing Germans about their militarist past (or at least the thoroughly shameful parts thereof) would never end, a new film depicts the life of the dashing Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen: better known to us as The Red Baron.

Our cunning cousin, the Hun, has cleverly concealed a card up his hunting-jacket sleeve. Just when you thought the continual winging by hand-wringing Germans about their militarist past (or at least the thoroughly shameful parts thereof) would never end, a new film depicts the life of the dashing Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen: better known to us as The Red Baron.

“Der Rote Baron” is showing in den deutschen Kinopalästen as we speak, but the motion picture was not actually meant for a German audience: this is but part of the clever ruse. The film was actually made in English and then dubbed back into German by the mostly Allemanic cast.

Having convinced us of their peaceful intentions through more than a half-century of “Guys, we really messed up circa 1933-1945”, the obvious intent is to swamp the English-speaking world with a film depicting the charming gentlemen fighters of the first weltkreig in order to disarm us as they prepare for their dastardly plans.

Why, as we speak, Georg Friedrich von Preussen is polishing his pickelhaube and dusting off his feather cap in preparation for this latest Prussian plot for world domination. While the Western world worried itself sick over global Islamism and the Chinese threat, little did we know that a swelling irredentism was brewing deep within the hearts of every Berliner; a tear developing in the eye at the mere mention of Tsingtao; a soul in mourning for the loss of Tanganyika. How naïve we were not to realize that all those bright young Germans spending their gap year teaching smiling Herero natives in Namibia were actually forward units of intelligence-gatherers yearning for the return of Ketmanshoop and Swakopmund to the Germanic fold.

Im wunderschönen Monat Mai

Als alle Knospen sprangen,

Da ist in meinem Herzen

Die Liebe aufgegangen.

Im wunderschönen Monat Mai,

Als alle Vögel sangen,

Da hab ich ihr gestanden

Mein Sehnen und Verlangen.

Philipp Freiherr von Boeselager, 1917-2008

Catholic Nobleman, Forester, Knight of Malta, Plotted to Kill Hitler

Philipp Freiherr (Baron) von Boeselager, the last surviving member of the conspiracy of anti-Nazi German officers, has died at 90 years of age. The freiherr‘s background and upbringing were distinctly Catholic. The Boeselagers are a Rhenish family with Saxon origins in Magdeburg. Philipp was the fourth of eight children and was educated by the Jesuits at Bad Godesborg. His grandfather had been officially censured by the Imperial German goverment for publically taking part in a Catholic religious procession.

Boeselager had most intimately been involved in the March 1943 plot to assasinate Hitler and Himmler when the the Fuhrer and the SS head were visiting Field Marshal Günther von Kluge on the Eastern Front. Boeselager, then a 25-year-old cavalry lieutenant under the Field Marshal’s command, was to shoot both Hitler and Himmler in the officers mess with a Walther PP. Himmler, however, neglected to accompany Hitler and so the Field Marshal ordered Boeselager to abort the attempt fearing that Himmler would take over in the event of Hitler’s death, changing nothing.

«Each day Hitler ruled, thousands died unnecessarily — soldiers, because of his stupid leadership decisions. And later, I learned of concentration camps, where Jews, Poles, Russians — human beings — were being killed.»

«Each day Hitler ruled, thousands died unnecessarily — soldiers, because of his stupid leadership decisions. And later, I learned of concentration camps, where Jews, Poles, Russians — human beings — were being killed.»

«It was clear that these orders came from the top: I realised I lived in a criminal state. It was horrible. We wanted to end the war and free the concentration camps.»

Boeselager later procured the explosives for the famous July 1944 plot (the subject of the upcoming film “Valkyrie“), under the cover of being part of an explosives research team. He handed a suitcase with the explosives on to another conspirator. When the bomb exploded in Hitler’s conference room, Boeselager and his 1,000-man cavalry unit made an astonishing 120-mile retreat in under 36 hours to reach an airfield in western Russia from where the aristocrat would fly to Berlin to join the other conspirators.

At the airfield, however, he received a message from his brother (Georg von Boeselager, a fellow cavalry officer who was repeatedly awarded for his consistent bravery on the battlefield) saying “All back into the old holes”, the code signifying the failure of the coup. Even more astonishingly than his swift retreat was his return, with his unit, to the front quickly enough not to raise any eyebrows. As a result, he was not known to be part of the conspiracy and escaped the gruesome tortures and executions dealt to many of his fellow conspirators.

After the war, his role in the plot was revealed and Philipp von Boeselager was awarded the Legion d’honneur by France and the Great Cross of Merit by West Germany. He joined the Order of Malta in 1946, eventually co-founding Malteser Hilfdienst, the medical operation of the German knights of the Order, and helping coordinate German pilgrimages to Lourdes.

The greater part of his post-war years was spent in forestry, and Boeselager served as head of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Deutscher Waldbesitzerverbände (the coordinating body of private and cooperative forest-owners) from 1968 to 1988. Coincidentally, he was succeeded in that post by Franz Ludwig Schenk Count von Stauffenberg, the son of the July ’44 plot mastermind.

“Valkyrie”

No, this isn’t a photograph of the latest Norumbega staff meeting, it’s a publicity shot from the upcoming United Artists film, “Valkyrie”. The film tells the story of Claus Philipp Maria Schenck von Stauffenberg, the heroic German Catholic noble who was the mastermind behind the July 20 plot against Hitler. Needless to say, there has been much anticipation over this film, especially since the lead role went to Tom Cruise, who has never quite got the knack of acting. Like Jeremy Irons, he seems to believe that completely different characters require little or no change in performance, but is mysteriously still making films nonetheless. (Cruise at least has the excuse of being a Scientologist to explain his success… what’s Jeremy Irons’s?).

Despite the poor choice of Mr. Cruise play Count Stauffenberg, the rest of the cast includes some pretty inspired choices. Playing Countess Nina von Stauffenberg is Carice von Houten (above), whom you will remember from “Zwartboek”. She’s joined by fellow “Zwartboek” actor Christian Berkel (top photo, seated far left), who played the evil General Kaütner in the Dutch film, the character responsible for the downfall of the good German, General Müntze, who was played by Sebastian Koch (better known for his role in the hit “Das Leben der Anderen”) who (pause for breath) actually played Count Stauffenberg himself in a 2004 German television production called “Stauffenberg”. Speaking of downfalls, Berkel (we’re back to him now) also played a nasty Nazi in the 2004 film “Downfall” depicting the last few days in Hitler’s bunker. [Correction: Berkel actually played Dr. Ernst-Günter Schenck, one of the good guys.] Some more of the cast…

(more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

- Waarburg October 2, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories