Books

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

Caro had been a Nieman Fellow at Harvard studying urban planning and land use when he came up with the idea for the book. He thought it would take him nine months, but extensive research and over five-hundred in-person interviews meant it took eight years to complete.

Caro then started working on his study of Lyndon Baines Johnson, the first volume of which emerged in 1982 and the fifth (and final?) one he is still working on. (At the end of the fourth, LBJ had just become president.)

But where does he write? Christopher Bonanos of New York magazine finds out:

It’s an ageless space, one where it could be last week or 1950 inside, matter-of-fact and utilitarian. A couple of bookcases, a plywood work surface, corkboard with outlines tacked up, an old brass lamp, an underworked laptop for emails, a Smith-Corona typewriter. The desk chair is hard wood with no cushion. There’s a saltshaker next to the pencil cup for when Ina brings a sandwich out at midday. The desk has a big half-moon cutout, same as the one back in New York, so he can rest his weight on his forearms and ease his bad back. That arrangement was recommended by Janet Travell, the doctor who grew famous for prescribing John F. Kennedy his Boston rocker. She, with Ina, is a dedicatee of The Power Broker.

He bought the prefab shack, he says, from a place in Riverhead for $2,300, after a contractor quoted him a comically overstuffed Hamptons price to build one. “Thirty years, and it’s never leaked,” he says. This particular shed was a floor sample, bought because he wanted it delivered right away. The business’s owner demurred. “So I said the following thing, which is always the magic words with people who work: ‘I can’t lose the days.’ She gets up, sort of pads back around the corner, and I hear her calling someone … and she comes back and she says, ‘You can have it tomorrow.’”

Does he write out here every day? “Pretty much every day.” Weekends too? “Yeah.” Does he go out much while he’s on the East End? “We have two friends who live south of the highway, and I said to Ina, aside from them, I’m not going this year.” There are other writer friends nearby in Sag Harbor, and they get together, but at this age, Caro admits a little sadly, they’re thinning out. He’ll be 89 this fall.

■ George Grant is a still-underappreciated giant of political thinking in the English-speaking world. He is too little known outside his native Canada, which he sought to defend from the undue overwhelming influence of its sparkling and glamourous southern neighbour. Next year marks the sixtieth anniversary of his Lament for a Nation.

Of all people, a research fellow at Communist China’s Institute for the Marxist Study of Religion — George Dunn — has written a thoughtful introductory overview of Grant’s life and thinking: George Grant and Conservative Social Democracy in Compact.

■ Katja Hoyer mused on an overlapping theme in a recent Berliner Zeitung column which she has helpfully presented in English as well:

A diplomat close to the SPD recently told me that he couldn’t understand why working-class people in particular voted for the AfD. Things weren’t so bad for them, after all. I didn’t bother pointing out that rampant inflation, high energy prices and rising rents have had a hugely detrimental effect on the living standards of people with low and middle incomes because his analysis completely misses the point.

Germany’s working-class voters, Katja argues, feel forgotten by the parties founded to represent them.

■ Since the fall of the Berlin Wall — and earlier in Angledom — political conservatism has effectively been taken over by economic liberalism.

This has denied the centre-right from learning from and deploying useful experience from outside liberalism, with the wisdom of figures as varied as Benjamin Disraeli, Giorgio La Pira, Charles de Gaulle, and Thomas Playford essentially ignored or sidelined.

Kit Kowol’s new book Blue Jerusalem: British Conservatism, Winston Churchill, and the Second World War explores the visionary side of wartime Conservatism. Dr Francis Young offers his take on Tory utopias in The Critic.

■ From a similar era, Andrew Ehrhardt writes at Engelsberg Ideas on Ernest Bevin and the moral-spiritual dimension of British foreign policy.

■ Our friend Samuel Rubinstein has studied at Oxford, Leiden, and the Sorbonne — technically the oldest universities in their three respective countries (although we all know that Leuven is in fact the doyen of Netherlandish academies).

Sam offers an incredibly interesting comparison of the experiences of these three institutions in a humble essay on his Odyssean education:

I arrived in Leiden, armed with my phrase-book, with some ambitions of learning Dutch. The first blow came at the Starbucks in the train station, when the barista answered my Ik wil graag in English without hesitating. The second came the following day when I tried again, at a different café – only this time it seemed that the barista (Spanish? Italian?) didn’t know much Dutch either: even the natives were placing their orders in English. So I gave up – save one hobby, reading Huizinga in the original. I got myself an attractive coffee-table edition of Herfsttij and managed a page or so a day, strenuously piecing it together from my English, German, and smattering of Old English. I still haven’t the faintest idea how to pronounce any of it.

■ And finally, those of us who love Transylvania will enjoy Toby Guise’s summary of the Fifth Transylvanian Book Festival in The New Criterion.

Why do you read?

We were both attending one of those formal dinners that punctuate the terms of the year so, as I was going to see him anyhow, I gave in.

With his kind permission, it is reproduced here:

I truly have no idea. I’ve never stopped to think about it. It’s probably a compulsion of some kind. I’ve always been a firm believer that some things you must stop yourself every now and then and analyse and there are other things you should never question and just accept. Reading falls in the latter category.

You’re a very social person though.

So I’m told.

And you live in London – a very social place. Is it difficult to get reading in then?

Yes and no. You need to force yourself to read before bed. It’s important to always have a book on the go. If you’re in London you’ve got tube journeys or the bus or whatever as you get from A to B. You have to maximise that time. Put it to use.

That’s why all books should be available in handy paperback editions that can fit in your coat pocket. This is much easier in winter when you’ve got a coat. In summer – also an excellent reading season in many ways – I don’t like feeling encumbered. I don’t like to carry things around. So unless it’s an old Penguin size – the perfect size – that I can slip into my back pocket then I tend not to read on the go.

You’re very passionate about book design and production.

I’m very correct about book design. It is unfathomable how incredibly and completely wrong the entire publishing sector in the English-speaking world is. I know the grass is always greener, but I’ve pointed out again and again how much better it is in France and also Germany a bit. Germany for the classics they have those excellent Reclam editions – Universal-Bibliothek – that are so useful. They are dirt cheap, small size, the easiest thing in the world to purchase, read, use, carry around. Insanely practical.

In backwards Angledom meanwhile every new book comes out in clunky hardback first and you have to wait a year or sometimes longer before you can get it in a form human beings can use. Why? Okay, maybe someone likes sitting in an armchair in their “study” smoking a pipe and reading a hardback book — D. W-B in Edinburgh, I imagine. Good for them. Do you really think that’s most people? I don’t have a commute – I have a fifteen-minute walk to work – but who wants to lug a massive hardcover on a train or a tube? Ridiculous.

But you’ve…

Another thing! It’s also perfect proof of the lies that the liberal capitalists would have us believe. They contend that if there’s a market for something it will just magically appear and the need will be fulfilled. Balderdash of the highest order. Culture exists. And publishing culture in the English-speaking world ordains you must publish the clunky cumbersome version first and then wait to issue a paperback version. Oh and when the paperback edition comes out it’s also too big in size. If ever I wield supreme dictatorial power you better believe I’d be forcing a return to the old Penguin size. Penguin don’t even use it anymore. Idiots.

But you’ve said you don’t read living writers so I guess you’re not buying newly published books anyway.

Okay, yes, maybe. Everyone knows to be a writer worth reading you’ve got to be dead. Turns out this isn’t exactly true. There are actually a good number writers scribbling away today who are perfectly worth reading, even if maybe they’re not high literature and they won’t end up in the Pantheon. Middle-brow – even popular novels – can be extremely enjoyable and worthwhile. They use up a different part of your brain. But they can be exceedingly clever. Just look at detective fiction. Agatha Christie. Insane talent, deployed in a very specific fashion. Not Shakespeare, not Racine…

Racine was a dramaturge, not a novelist.

Ooooh! Look at you! “Dramaturge”. You mean a playwright, a dramatist. “Dramaturge.” I mean really… Racine was a writer, tout court. You know what I mean. Incidentally I bought some French drama recently. Molière.

You’ve been involved in some French drama recently.

In a manner of speaking… [Several sentences of this interview redacted from public display to protect the guilty.]

…But I’ve got Molière on my pile for this winter.

Do you read a lot of French writers?

Hmm… No… Maybe? No, I don’t think so. I try and keep abreast of things. I probably read more Arabs at the moment. Right now I’m in the middle of Amara Lakhous: Clash of Civilizations Over an Elevator in Pizza Vittorio. So far it’s very clever, very human. But Lakhous is an Arab in Europe. Or is he in New York now these days? But he was in Italy for years and writes in Italian sometimes and in Arabic.

Majdalani. Charif Majdalani: he’s a proper Arab writer. Lives in Beirut.

He used to work in France though.

Okay, okay, yes. But he’s a proper Lebanese writer, alive too. I think he’s teaching at Saint-Joseph. I have him on my pile at home but I haven’t read him yet.

A little lighter – well, not in subject matter – but I’d like to read Yasmina Khadra, the pseudonym of the Algerian detective writer Moulessehoul.

Khadra lives in France, too.

Okay! Yes! I get it! Maybe you’d live in France too if you were an ex-army officer who criticised Bouteflika. Anyhow. His police novels, they’re Algiers. Gritty. I need to read them.

Lakhous is clever though – I hope not too clever. A little whimsical. It’s the world of the non-European in Europe. Chika Unigwe writing the experience of Nigerians abroad. Her writing has a very basic primalness to it.

But the non-Euro experience of Europe: Maybe there’s not enough of that – or maybe there is but it’s done by crap writers who are praised just for their backgrounds. Turns out there’s no need because there are actually good writers doing things.

But there’s plenty of rubbish. In general.

Oh ho ho – so much rubbish. But you can just ignore that. Never get distracted by it. Life’s too short.

You’ve often said that people need to curate their attention span.

Yes! Yes! A thousand times yes! There’s so much beauty in the world, whether in real life or in art and writing and plays and everything. You will be so much better off if you just ignore the crap. It’s not worth your attention. It sure as hell ain’t worth mine.

Who else of the Arabs?

Alaa al Aswany – is he any good?

I haven’t read him. You live in London: how do you keep up with Arab writers?

Oh you just do, somehow. Via French for one thing. Keep your eyes on Le Figaro littéraire. They’re in there a lot and then you have to see if they’ve been translated into English. Often you find the author but not the latest as they’re either written in French or translated into it pretty quickly. But you hear about a writer and you see what’s been translated into English. And obviously L’Orient littéraire is superb for trying to get to know the ecosystem of Arab writers. And Arablit Quarterly.

Do you read novels in French?

No – my French is actually terrible. I’m good at reading things like newspapers and non-fiction in French. Probably misunderstanding half of it, but good enough. I cannot read fiction in French, not good enough. Or maybe I just don’t try.

At a sort-of conference the other day, Adrian Pabst — what a gent he is — he introduced me to some visitors as a “fellow francophone”. Generous — I had to correct him. Anyhow, I need to learn French better. Tout le monde civilisé parle, lit et pense en français.

Est-ce que tu es civilisé ?

Ah! Nous – les celtes, les anglais, whatever – on est un peu des barbares. But the light of civilisation has fallen upon us as well. Celts in particular – I think we like to do things with words. We can deploy them in amazing subterfuges.

And then there’s Stoppard.

Stoppard: the nexus of Jewry, Mitteleuropa, and the English language.

Precisement. I know he’s a show-off. Everyone always says he’s a show-off. But come on, he’s amazing.

By the way, this is my first year where I will have in one calendar year seen three different Stoppard productions. ‘The Real Thing’ at the Old Vic – that was brilliant, just ended – and earlier ‘Rock ’n’ Roll’ at the Hampstead Theatre. Nathaniel Parker, excellent on stage.

I love going to the Hampstead Theatre because the congregation is very Jewish and it makes me feel at home.

New York.

Exactly. And then next month there’s something at… well I don’t know which theatre. Or which play.

The Invention of Love?

Yes! The Invention of Love.

That’s also the Hampstead Theatre.

Perfect. I think the first Stoppard I saw was there. They’re into him. I think he’s into them, too.

What about history though? What history are you reading?

You know, the American colonial period and the early republic have produced so much historical writing. A lot of it is very good. Okay, a lot of it is crap, too. There’s far too much pious nonsense – all that Founding Father worship, it’s excessively tiresome. Jefferson? Nein danke! Did you see they took the statue of Jefferson out of [New York’s] City Hall? Yeah they did it for the wrong reasons but – why was he there to begin with?

He’s Virginian.

He’s Virginian! And not one of the good ones! But there are so many interesting characters and amazingly accomplished people. I find George Washington boring but there are so many fascinating people from this time. You just have to avoid the pious stuff that a certain kind of respectable established American writer type can write about them.

There’s that wonderful institute at William & Mary.

I thought you were anti-Virginian.

I’m pro William & Mary. The college, that is – definitely not the monarchs. Anyhow, they have this institute for early American history and it publishes excellent historical stuff. Has done for decades. They have a quarterly journal.

Favourite Virginian writer?

Poe. Am I allowed to say Poe? Was he a Marylander?

He was born in Boston.

We won’t hold that against him. Baltimore claims him. No one associates him with Boston. I think his formative years were in Virginia. He was kicked out of West Point. And we also have Poe Cottage in New York.

Is Poe a good writer for Hallowe’en?

Oh of course. Reading is very seasonal, isn’t it? I only got into that horror stuff – what do you call it? Gothic, I guess. I only started enjoying that a few years ago. We read Poe at school, of course. But a few years ago, one winter’s evening — I was at a dinner at Boodle’s and sitting next to a princess…

Finally, the name dropping. I was warned it would come.

Just for that I won’t say which. Well she started going on about M.R. James and how brilliant he was and his stories and the settings and everything, so I got into M.R. James. And I read all his short stories. Or maybe they were just the Penguin selected ones? Anyhow, I told this to my friend – my best friend, in fact – and he said he’d recommended M.R. James to me years ago and I did nothing about it. Oh well. Sometimes you need someone to tell you things in the right setting, the soft candlelight, the gentle murmur of a table full of people in a hall… Robertson Davies! His ghost stories as well. He was made head of Massey College at Toronto — basically the All Souls of Toronto — and would write a new ghost story every year to be read aloud after some annual dinner in hall.

Speaking of which, I believe we’re being called in to dinner.

Procedamus.

Thank you.

Thank you.

A Prize for the General

France’s Top Military-Literary Prize Awarded to François Lecointre

IT SHOULD surprise no-one that the French Army awards an annual prize for military literature. Since 1995, the Prix littéraire de l’Armée de terre – Erwan Bergot is awarded every year for “a contemporary work of French literature that demonstrates active commitment, of a true culture of audacity in service to the collective whole” and is named in memory of the paratrooper officer, writer, and journalist Erwan Bergot (1930-1993).

This year’s prize has been awarded to Gen. François Lecointre, the former Chief of the Defence Staff who now serves as the Chancellor of the Légion d’honneur.

This year’s prize has been awarded to Gen. François Lecointre, the former Chief of the Defence Staff who now serves as the Chancellor of the Légion d’honneur.

A graduate of Saint-Cyr, Lecointre’s book Entre Guerres (Between Wars) relays his long service to France in the land forces, including operations in Central Africa, Rwanda, Bosnia, the First Gulf War, and elsewhere.

As a young captain in Bosnia, Lecointre was concerned when his company lost radio contact with the French UNPROFOR observation post on Vrbana bridge early on the morning of 27 May 1995. When he went himself to investigate, Captain Lecointre discovered that Bosnian Serb soldiers in captured French uniforms had seized the post and taken French soldiers hostage.

Lecointre immediately informed Paris, where President Jacques Chirac circumvented the UN chain of command in Bosnia by allowing soldiers under Lecointre’s command to retake the post on the northern end of the bridge with a bayonet charge that overran the Serb-held bunker. Vrbana bridge is believed to have been the last bayonet charge of any French military operation to date.

General Pierre Schill, Chief of the Army Staff, awarded his comrade-in-arms the Prix Erwan Burgot this weekend. The prize includes a monetary award of €3,000 which Gen. Lecointre has donated to the association Terre Fraternité that provides support to France’s wounded soldiers and their families.

Entre Guerres had already won the Prix Jacques-de-Fouchier awarded by the Académie française earlier this year. (Above: Gen. Lecointre with the académicien, lawyer, and writer François Sureau.)

The Erwan Burgot prize’s jury was chaired by Gen. Schill and included the son and widow of Erwarn Burgot, alongside Col. Loïc de Kermabon, Col. Noê-Noël Uchida, the journalist and writer Guillemette de Sairigné, literary figure Laurence Viénot, Général de Division Jean Maurin, Général de Brigade Gilles Haberey, prix Goncourt winning novelist Andreï Makine, writer Christine Clerc, former head army medic Dr Nicolas Zeller, journalist Jean-René Van Der Plaetsen, Professor Arnaud Teyssier, and the historian François Broche.

Articles of Note: 13 March 2024

My then-flatmate was getting married the next day and much pottering-about sorting things was required but the idiosyncratic beauty of this building captured my imagination — part Norman, part Moorish. I was almost insulted that I hadn’t come across it in any of my bookish explorations.

The historian Edmund Harris covers Chideock in his lusciously illustrated post on Recusancy in Dorset and the ‘other tradition’ of Catholic church-building.

■ Generations ago it was said that the three institutions no British politician dared offend were the trade unions, the Catholic Church, and the Brigade of Guards. In 2020s Britain there is only one caste which must always be obeyed: the ageing, moneyed homeowners.

Not only do these “NIMBYs” (“Not In My Back Yard”) jealously guard their freeholds, they do whatever they can to prevent more houses being built to guard the value of their prize possessions, vastly inflated by a combination of lacklustre housebuilding and irresponsible leap in migration. As old people vote and young people don’t — and when they do, vote badly — few sensible people can find a way out of this quagmire.

It might be worth looking to the Mediterranean, where Tal Alster tells us How Israel turned urban homeowners into YIMBYs.

■ It’s disappointingly rare to see intelligent outsiders give a considered impression of the current state of play in the Netherlands — that’s Mother Holland for us New Yorkers. Too often commentators in English are either rash cheerleaders for the hard right or bien-pensant liberals eager to castigate and chastise. Both rush to judgement.

What a rare diversion then to read Christopher Caldwell — the only thinking neo-con? — attempt to explore and explain the success of Geert Wilders in the recent Dutch elections.

■ One in ten of Lusitania’s inhabitants are now immigrants, and this discounts those — many from Brazil and other former parts of the once-world-spanning Portuguese empire — who have managed to acquire citizenship through various routes.

Ukrainian number-plates are now frequently be seen on the roads of Lisbon, as far in Europe as you can get from Big Bad Uncle Vlad.

Vasco Queirós asks: Who is Portugal for?

■ Speaking of world-spanning empires, in true andrewcusackdotcom fashion, we haven’t had enough of the Dutch — but we have had enough of their wicked wayward heresies.

Historian Charles H. Parker explores the legacies of Calvinism in the Dutch empire.

■ The City of New York itself is the best journalism school there is. Jimmy Breslin dropped out of LIU after two years, eventually taking up his pen. Pete Hamill left school at fifteen, apprenticed as a sheet metal worker, and joined the navy.

William Deresiewicz argues that a dose of working-class realism can save journalism from groupthink.

■ The New Yorker tells us how a Manchester barkeep found and saved a lost (ostensible) masterpiece of interwar British literature.

■ Our inestimable friend Dr Harshan Kumarasingham explores David Torrance’s history of the first Labour government on its hundredth anniversary.

■ And finally, one for nous les normandes (ok, ok, celto-normandes): Canada’s National Treasure David Warren briefly muses that the Norman infusion greatly refined Anglo-Saxon to give us the superior English tongue we speak today.

The Ukrainians’ Secret Weapon

For those looking for an explanation as to the notable success of the Ukrainians on the battlefield in the current unpleasantness taking place in their country, look no further.

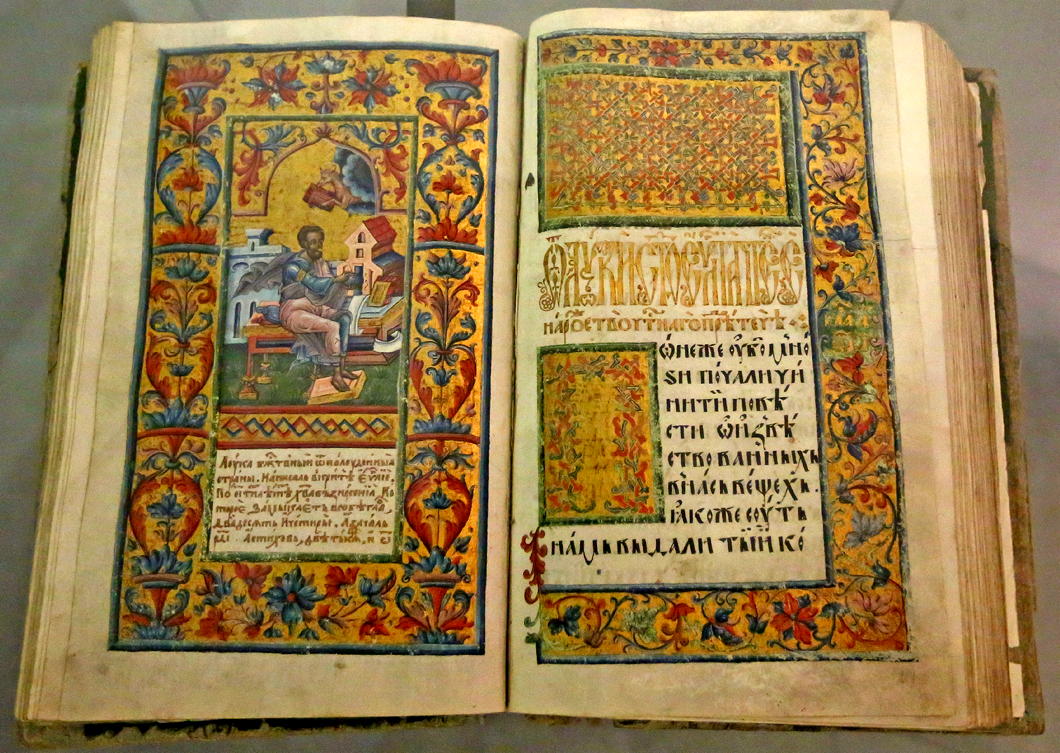

In a thread of tweets, the biblophile Incunabula reveals the Ukraine’s secret weapon: the Peresopnytsia Gospels (Пересопницьке Євангеліє).

“All six Ukrainian Presidents since 1991,” Incunabula writes, “including Volodymyr Zelensky, have taken the oath of office on this book: the sixteenth-century Peresopnytsia Gospels, one of the most remarkably illuminated of all surviving East Slavic manuscripts.”

“The Peresopnytsia Gospels were written between 15 August 1556 and 29 August 1561, at the Monastery of the Holy Trinity in Iziaslav, and the Monastery of the Mother of God in Peresopnytsia, Volyn.”

“This manuscript is the earliest complete surviving example of a vernacular Old Ukrainian translation of the Gospels. Its richly ornamented miniatures belong to the very highest achievements of the artistic tradition of the Ukrainian and Eastern Slavonic icon school.”

“The Peresopnytsya Gospels were commissioned in 1556 by Princess Nastacia Yuriyivna Zheslavska-Holshanska of Volyn, and her daughter and her son-in-law, Yevdokiya and Ivan Fedorovych Czartoryski. After its completion the book was kept in the Peresopnytsya Monastery.” (more…)

Christmas Book List 2022

A reading list for the festive season

Instead, I will give an actual Christmas book list — namely, a list of books I intend to read this Christmas, snuggled up in whatsoever sufficient level of coziness I manage to achieve.

If you want to read a partial selection of books I’ve already finished reading, there is a Twitter thread you can consult (though, naturally, it doesn’t list everything).

But here are the eight books I’m looking forward to devouring.

Thomas Pink is now Emeritus Professor of Philosophy at King’s College London but he is no less busy since he has several volumes either to write or to edit on his to-do list. As a natural polymath with many interests, Tom is one of the best book-recommenders I have the privilege of knowing.

Last time we had a drink he put forward Mary Hollingsworth’s Conclave 1559: Ippolito d’Este and the Papal Election of 1559. It’s the only one on my Christmas reading list I’ve already jumped right into, and it’s excellent so far.

Last time we had a drink he put forward Mary Hollingsworth’s Conclave 1559: Ippolito d’Este and the Papal Election of 1559. It’s the only one on my Christmas reading list I’ve already jumped right into, and it’s excellent so far.

This is a period of European (and world) history I’ve not devoted any great study to, so Hollingsworth’s accounts almost attains the level of a political thriller. She’s skilled at combining archival research with an eye for the enlightening detail, which makes Conclave 1559 an enjoyable read.

Another history on my list is Last Train to Paradise: Henry Flagler and the Spectacular Rise and Fall of the Railroad That Crossed an Ocean by Les Standiford. As a child visiting the colonial city of St Augustine in Florida I remember seeing some of the extraordinary Spanish revival buildings Henry Flagler erected as part of his rail-and-hotel conglomerate.

Another history on my list is Last Train to Paradise: Henry Flagler and the Spectacular Rise and Fall of the Railroad That Crossed an Ocean by Les Standiford. As a child visiting the colonial city of St Augustine in Florida I remember seeing some of the extraordinary Spanish revival buildings Henry Flagler erected as part of his rail-and-hotel conglomerate.

Florida as we know it today was practically invented over a century ago when Flagler built his Florida East Coast Railway to bring northerners down to the Sunshine State. From 1905 to 1912 he managed a feat of engineering by extending the line across the Florida Keys.

Lawrence Durrell, despite never being a UK citizen thanks to quirks of Indian birth and bureaucracy, spent a few spells of his life working for the British diplomatic service. He’s most famous for his ‘Alexandria Quartet’, but it is White Eagles Over Serbia — a tale of a British agent caught between communists and royalists in post-war Yugoslavia — that has made it to my festal reading list.

Lawrence Durrell, despite never being a UK citizen thanks to quirks of Indian birth and bureaucracy, spent a few spells of his life working for the British diplomatic service. He’s most famous for his ‘Alexandria Quartet’, but it is White Eagles Over Serbia — a tale of a British agent caught between communists and royalists in post-war Yugoslavia — that has made it to my festal reading list.

Exotic tales of derring-do were the stock in trade of Sir H. Rider Haggard, but I have to admit I’ve never read anything by this popular Victorian/Edwardian writer.

Exotic tales of derring-do were the stock in trade of Sir H. Rider Haggard, but I have to admit I’ve never read anything by this popular Victorian/Edwardian writer.

Rectifying this error, King Solomon’s Mines is on my Christmas pile (though I was tempted by She as well).

I love a good detective novel, and the undoubted Queen of Mystery is Dame Agatha Christie. The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding is a collection of short stories including both Miss Marple and Hercules Poirot.

I love a good detective novel, and the undoubted Queen of Mystery is Dame Agatha Christie. The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding is a collection of short stories including both Miss Marple and Hercules Poirot.

In case I don’t get my fill of ze little grey cells I’ve grabbed a copy of Hercule Poirot’s Christmas as well.

A trip back to my Heimat of New York is provided by Ludwig Bemelmans’ Hotel Splendide. More famous for creating the Madeleine series of children’s books, Bemelmans immigrated to America before the First World War, volunteered for the U.S. Army, and worked at several hotels and restaurants. These latter experiences resulted in this comic novel about life behind the scenes in a swish Manhattan hotel.

A trip back to my Heimat of New York is provided by Ludwig Bemelmans’ Hotel Splendide. More famous for creating the Madeleine series of children’s books, Bemelmans immigrated to America before the First World War, volunteered for the U.S. Army, and worked at several hotels and restaurants. These latter experiences resulted in this comic novel about life behind the scenes in a swish Manhattan hotel.

Having been previously introduced to the character of Sir Edward Leithen, I thought it might be worth catching up with him in John Buchan’s The Gap in the Curtain.

Having been previously introduced to the character of Sir Edward Leithen, I thought it might be worth catching up with him in John Buchan’s The Gap in the Curtain.

The Scots barrister and Tory MP is introduced to a brilliant physicist and mathematician who explains his theory on the workings of time and the cryptic ability to see into the future. Buchan is a reliable storyteller with admirable instincts, though this series of stories veers into the realms of science fiction.

But Christmas is a light-hearted time, and so my Christmas reading list finishes with a visit to Blandings Castle thanks to Sir Pelham Grenville Wodehouse’s Leave it to Psmith.

But Christmas is a light-hearted time, and so my Christmas reading list finishes with a visit to Blandings Castle thanks to Sir Pelham Grenville Wodehouse’s Leave it to Psmith.

The ‘p’, of course, is silent — “like in ‘pshrimp’”.

The Headless Horseman & Hallowe’en

Washington Irving’s Legend of Sleepy Hollow — perhaps better known as the tale of the Headless Horseman — is inevitably and almost universally linked to the great feast of Hallowe’en.

There are obvious reasons for this in that Hallowe’en has become the festival of ghoulish otherworldliness, sadly now devolved into plastic mawkishness in a manner old followers of the Knickerbocker ways must surely condemn and mourn.

But this tale is always worth a revisiting; even now in early Advent.

Irving purists — we exist — might point out there there is no indication Ichabod Crane’s fateful evening ride through the Hollow took place on Hallowe’en.

Indeed, Hallowe’en is not mentioned at all in the text of the Legend, and all the author shares with us regarding the date is that it was “a fine autumnal day”:

…the sky was clear and serene, and nature wore that rich and golden livery which we always associate with the idea of abundance.

The forests had put on their sober brown and yellow, while some trees of the tenderer kind had been nipped by the frosts into brilliant dyes of orange, purple, and scarlet.

Streaming files of wild ducks began to make their appearance high in the air; the bark of the squirrel might be heard from the groves of beech and hickory-nuts, and the pensive whistle of the quail at intervals from the neighboring stubble field.

It makes for a luscious harkening of old Westchester and the Hudson Valley in the early days of the republic.

Tastier still is the scene set as the Yankee newcomer Crane enters the home of an old Dutch household for the evening’s revelries:

Fain would I pause to dwell upon the world of charms that burst upon the enraptured gaze of my hero, as he entered the state parlor of Van Tassel’s mansion.

Not those of the bevy of buxom lasses, with their luxurious display of red and white; but the ample charms of a genuine Dutch country tea-table, in the sumptuous time of autumn.

Such heaped up platters of cakes of various and almost indescribable kinds, known only to experienced Dutch housewives!

There was the doughty doughnut, the tender oly koek, and the crisp and crumbling cruller; sweet cakes and short cakes, ginger cakes and honey cakes, and the whole family of cakes.

And then there were apple pies, and peach pies, and pumpkin pies; besides slices of ham and smoked beef; and moreover delectable dishes of preserved plums, and peaches, and pears, and quinces; not to mention broiled shad and roasted chickens; together with bowls of milk and cream, all mingled higgledy-piggledy, pretty much as I have enumerated them, with the motherly teapot sending up its clouds of vapor from the midst—Heaven bless the mark!

I want breath and time to discuss this banquet as it deserves, and am too eager to get on with my story.

Happily, Ichabod Crane was not in so great a hurry as his historian, but did ample justice to every dainty.

So celebrate Hallowe’en not with plastic costumes and cheap trinketry but with Dutch delicacies and tasty treats. (And for helpful suggestions, see Peter G. Rose’s Food, Drink, and Celebrations of the Hudson Valley Dutch.)

Put aside the vampire capes and risqué nurses’ kit and, amidst candles and pumpkins of all shapes and sizes, think of the Dutch Hudson of long ago that lingers still in heart and mind.

Ödön von Horváth

When the shop purveying diacritical marks opened one morning in Vienna, in my mind the writer Ödön von Horváth turned up and said “Thanks. I’ll have the lot.”

It wasn’t even his real name, of course — which was Edmund Josef von Horváth. A child of the twentieth century, von Horváth was born in Fiume/Rijeka in 1901. His father was a Hungarian from Slavonia (in today’s Croatia) who entered the imperial diplomatic service of Austria-Hungary and was ennobled, earning his “von”.

“If you ask me what is my native land,” von Horváth said, “I answer: I was born in Fiume, grew up in Belgrade, Budapest, Preßburg, Vienna, and Munich, and I have a Hungarian passport.”

“But homeland? I know it not. I’m a typical Austro-Hungarian mixture: at once Magyar, Croatian, German, and Czech; my name is Hungarian, my mother tongue is German.”

From 1908 his primary education was in Budapest in the Hungarian language, until 1913 when he switched to instruction in German at schools in Preßburg (Bratislava) and Vienna.

Von Horváth went off to Munich for university studies — where he began writing in earnest — but quit midway through and moved to Berlin.

He once told his friends the story of when he was climbing in the Alps and stumbled upon the remains of a man long dead but with his knapsack intact.

Intrigued, he opened the knapsack and found an unsent postcard upon which the deceased had written “Having a wonderful time”.

“What did you do with it?” his friends naturally inquired. “I posted it!” was von Horváth’s reply.

In 1931 he was awarded the Kleist Prize for literature, but two years later the National Socialists took the helm and von Horváth thought it best to move across the border to his old imperial capital of Vienna.

Despite his anti-nationalism, he did initially join the guild for German writers set up by the Nazis, possibly to keep his works in print in the Reich while he was living in still-independent Austria.

It was in Vienna he published his best-known work: Jugend ohne Gott — “Youth without God” (first translated into English as The Age of the Fish), which marked his public point-of-no-return break with the Hitlerites.

The novel depicts a jaded schoolteacher increasingly disconnected from his profession and the world around him as the ideology of National Socialism begins to take root in the education system. (Bizarrely, it was also scantly used as the basis for a 2017 dystopian thriller.)

When Hitler’s troops marched into Austria the following year, von Horváth fled to Paris.

“I am not so afraid of the Nazis,” he told a friend there one day. “There are worse things one can be afraid of, namely things you are afraid of without knowing why. For instance, I am afraid of streets. Roads can be hostile to you, can destroy you. Streets frighten me.”

Days later, in the middle of a thunderstorm, von Horváth was walking down the Champs-Élysées — the most famous street in Paris — when a flash of lightning struck a tree, felled a branch, and struck the writer dead. He had been on his way to the cinema to see Walt Disney’s ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs’.

Years ago someone recommended The Eternal Philistine: An Edifying Novel in Three Parts to me, but I have to admit I haven’t yet read it, or much else of von Horváth’s work. (He’s on my fiction wish-list though.)

His plays have been revived, too — here in London at the Almeida and the Southwark Playhouse in the past decade or so — and both The Eternal Philistine and Youth Without God are available in English from the estimable Neversink Library imprint of Melville House.

Mistranslating Apostates

ONE OF THE historical anecdotes I enjoyed being taught at school was the death of the Emperor Julian the Apostate — as relayed by our much-esteemed teacher Dr Nathaniel Kernell. This was in the Christian era with the capital at Constantinople rather than the Eternal City itself — Julian had (as betokened by his moniker) abandoned Christianity aged 20 and sought to frustrate its spread.

He wanted to promote the old Greek gods, dabbled in vegetarianism, and even tried to rebuild the Temple of Jerusalem. Mysterious fires consumed the workers tasked with that final project and it is presumed many Jews didn’t want to be dragged into the Emperor’s political project the animus of which was opposition to Christianity rather than promotion of Judaism.

Anyhow, none of Julian’s projects came to much fruition and as he lay dying from an injury in battle, the apostate emperor realised the futility of his life’s work with his final words: νενίκηκάς με, Γαλιλαῖε, or ‘Thou hast defeated me, Galilean!’

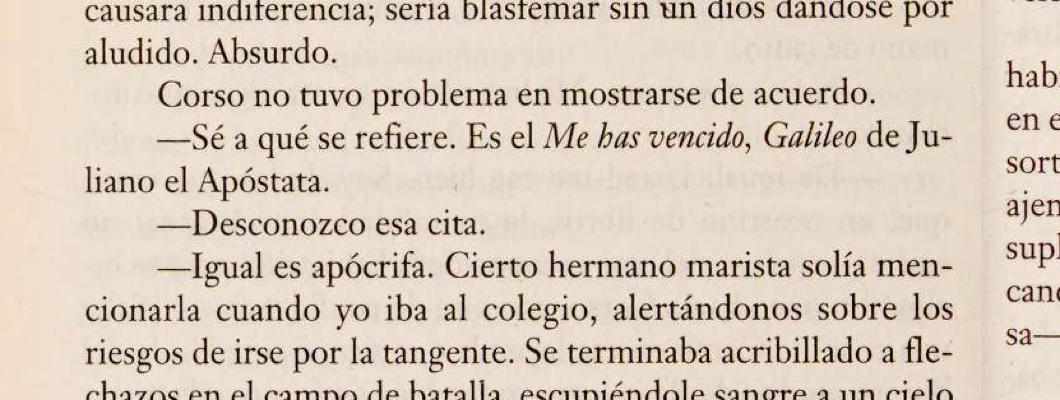

At the moment I am reading a book by Arturo Pérez-Reverte and stumbled across a mistranslation from the Spanish that would have been avoided if only the translator had enjoyed the privilege of being taught by Dr Kernell.

It turns out that the Spanish word for ‘Galilean’ is ‘Galileo’. Pérez-Reverte’s translator, alas, failed to understand one of the characters reference to Julian’s final words and mistook Christ our Saviour for an Italian astronomer, mistranslating the phrase as “You have defeated me, Galileo”.

Worth a wry smile, given the solid 1,200-year gap between the death of Julian the Apostate and the birth of Galileo Galilei.

The Dumas Club is a delightfully weird and intriguing tale, though, and I look forward to reading more by Pérez-Reverte — no matter who the translator is.

Three Bedrooms in Manhattan

Helena at Bethlehem

He sent along this passage from Waugh’s novel Helena in which the saint (and mother of the Emperor Constantine) arrives at Bethlehem, the city of Our Saviour’s birth, on the very feast of the Epiphany. She addresses the Magi in prayer.

“Like me,” she said to them, “you were late in coming. The shepherds were here long before; even the cattle. They had joined the chorus of angels before you were on your way. For you the primordial discipline of the heavens was relaxed and a new defiant light blazed among the disconcerted stars.

“How laboriously you came, taking sights and calculations, where the shepherds had run barefoot! How odd you looked on the road, attended by what outlandish liveries, laden with such preposterous gifts!

“You came at length to the final stage of your pilgrimage and the great star stood still above you. What did you do? You stopped to call on King Herod. Deadly exchange of compliments in which there began that unended war of mobs and magistrates against the innocent!

“Yet you came, and were not turned away. You too found room at the manger. Your gifts were not needed, but they were accepted and put carefully by, for they were brought with love. In that new order of charity that had just come to life there was room for you too. You were not lower in the eyes of the holy family than the ox or the ass.

“You are my especial patrons,” said Helena, “and patrons of all late-comers, of all who have had a tedious journey to make to the truth, of all who are confused with knowledge and speculation, of all who through politeness make themselves partners in guilt, of all who stand in danger by reason of their talents.

“Dear cousins, pray for me,” said Helena, “and for [the generally believed still unbaptized Emperor Constantine] my poor overloaded son. May he, too, before the end find kneeling-space in the straw. Pray for the great, lest they perish utterly. And pray for… the souls of my wild, blind ancestors…

“For His sake who did not reject your curious gifts, pray always for the learned, the oblique, the delicate. Let them not be quite forgotten at the Throne of God when the simple come into their kingdom.”

What Huxley’s Got on Orwell

Comparing dystopic visions of the English twentieth century

by ALEXANDER FRANCIS SHAW

Aldous Huxley wasn’t as good a writer as George Orwell but in several ways his Brave New World exceeds the prescience of 1984.

Huxley understood how society would respond if the laws of human ecology were to change. In a mechanised age, useless activity would become a necessity, while medical revolution and sexual deregulation in turn become the germ of totalitarianism. Orwell and just about everyone else since have had the opposite idea – that the libertines would be the liberators – and the fever-pitch of this very delusion forms the central tenet of Huxley’s dystopia.

Both visionaries describe state censorship, but in Huxley’s Brave New World one recognises eery pre-echoes of ‘Woke culture’ in an opiate-addled society which has to conceal its operational ethos from its own general consciousness in order to keep itself functioning smoothly.

With Orwell – the human struggle is represented as Man versus The State. Huxley recognised, as we are now encouraged not to, that society is the product of biology and, provided that people’s biology can be conditioned correctly, the state can foster grass-roots totalitarianism without the use violent coercion.

Neither dystopia has been fully realised – but in Orwell’s case this has been because progress has provided its own remedies (nobody could have imagined in the 1940s that telescreens would also be a conduit of private interaction for dissenters’ online discourse). One gets an unsettling feeling that Huxley’s medical dystopia is still developing in 2021 with no solutions in sight.

Rather than solve the riddle of human happiness, the citizens of Brave New World condemn those who fail to gloss over their displeasure with life through the mollifying comforts of sex and tranquillisers. Science becomes a branch of pragmatism, wielded by social engineers who can no more observe their own fields than look at their own eyeballs.

We are left with the question of how an outsider, possessed of higher directives than his own hedonism, might react to such a society?

Huxley answers this by introducing a Linda and her son, John, who live in a ‘savage reservation’ where medical advances have not been imposed. Traditional sexual morality is thus observed by the occupants along with – shudder! – family life and religious practices and other pursuits which lend meaning to their backward lives.

Linda arrived in the reservation by accident, having been born and acculturated in the ‘civilised world.’ She teaches her son how to read, but brings them both into disgrace with her promiscuity, so that John retreats into the comforts of a book which happens to be ‘The Complete Works of William Shakespeare.’ In Shakespeare, John finds the words that enable him to assert himself both on the reservation and – to the curiosity of his minders – when he finally returns to civilisation.

I sense that Orwell would have furnished John with a lowlier reference-point to human nobility and driven the same points home more poignantly with a dog-eared copy of Paris Match. But, as I said, Huxley was a better visionary than he was a wordsmith.

Once in the ‘civilised world’ John falls in love and faces a problem which, less than a century after Huxley’s work was published, defines what is perceived as a ‘crisis of masculinity’: how to court a woman who gives herself out to dozens of men regardless of merit. Unable to disabuse himself of his chivalric values – and unwilling to accept her worthless sexuality when she freely offers herself to him – John becomes what we would now call a proto-“incel” and dies, as the carnal realists of the toxic chatrooms might anticipate, on the end of a rope.

Smokescreens of happiness and delusion are maintained with a tranquilliser called Soma. Much as anti-depressants are a major feature of modernity – their use strongly suggesting that they are employed where artificial economies and casual sex are normalised – one senses that we have not yet perfected the Brave New World’s capacity for total bafflement. Nor has any welfare state or medical advancement completely collectivised the process of raising children.

This tranquillised social order is upheld by World Controller Mustapha Mond, Huxley’s benign analogue to Orwell’s Big Brother and on that account one of the few people in this dystopia who has achieved any kind of true satisfaction himself. Mond’s discourses bring Huxley to the place of scientific observation in the stable technological order:

‘once you start admitting explanations in terms of purpose – well, you don’t know what the result might be…’

In other words: Heaven forbid anyone should question the dogmas of settled science.

In terms of who may be allowed to see through the delusion, Mond likens the social hierarchy to an iceberg – with 10 per cent above the surface and 90 per cent below. Maverick, enquiring minds must either be sent to isolated communities or – like himself – shoulder the burden of everyone else’s delusion.

Despite Orwell’s predictions of people cowering under state tyranny and violence, Huxley’s work remains the creepier for its ability to get under the skin of the liberal society that we find familiar.

How much worse is it to read of a dystopia in which, by our own liberated will, we are complicit?

Get thee to a Lamasery

In defence of Lost Horizon

by ALEXANDER FRANCIS SHAW

Death hath no sting because I know that — on the other side of the planet — glass elevators whisper fifty-six storeys from a marble lobby to rooms of crisp white sheets and burgundy damask. The carpets are thick, the tables polished. Decanters are flushed with guava and grape. In a kaleidoscope of silver and ice, glasses of salad and sorbet are heaped with pearlescent foam, salmon and beluga.

And in one corner, in another time, Alexander Shaw fell asleep in the late afternoon, cheek pressed against the silk wing of an armchair as his gaze followed the plunge of a falcon from the Peak, through the skyscrapers, and out over Victoria Harbour. A soft audio moquette of Morrecone and Mahler accompanied the CNN news ticker and extraneous weather synopses: Sydney — sun… Los Angeles – overcast… Doha – sun… Cape Town – rain…

Please excuse the fetishism. My point deserves this tantric preamble.

If Pugin had been a Qing rather than a Victorian he might have made a start to all this, but today the backlit Onyx, the Pacific sixteen-storey silk frieze, the Qipao uniforms, and the Olympian scale of everything behove only the mighty Orient.

Why so? The Island Shangri-La Hotel is named for the fictional utopia in James Hilton’s Lost Horizon. And right there you have the problem: ‘utopia.’ The martial cultures of the East don’t comprehend the pre-echoes in that word.

Credit where it is due, the sublimation of the individual into the Gestalt (I’ll call it Gung-Ho, because that sounds like a legitimate school of oriental philosophy) is in stark contrast to the game we play with ourselves the West. Because they’ve never been saddled with accountability for the state of their societies, the Chinese haven’t had the opportunity to be disillusioned by their own idealism. A Chinese man has never had to look at himself in the mirror and realise that he buggered things up by voting for Hitler or joining a Black Lives Matter march.

Absent any higher purpose, we, on the other hand, must seek redemption for each hypocrisy and failure of our great civilisation, dumbing down in hand-wringing apologia for our very existence. Thus have we developed a misnomered ‘meekness’ of niceness, indecision, and half-measures. To believe in our superiority is to be saddled with shame – and shame is a force distinct from guilt in that it seeks remission by reference to others’ perception. You can quietly abort a child with Down Syndrome provided that you demonstrate your humanity by promoting BAME representation, carbon austerity, and the moxie of women who have the mystique of cement mixers.

A second example: the lobby-girl at the Grand Hyatt, Shanghai. Given that half the wealth of the Orient passes through those doors, some central planning committee evidently felt it prudent that the city’s 24 million citizens be combed for the sweetest smile to greet it. When I returned, breath held, a year later, she had been matched by another matchless angel.

Which brings us to the human source of utopianism – the quest for eternity. The plane-wrecked protagonists of Hilton’s novel experience a Himalayan valley of youth governed by an AWOL and arguably mad 250-year-old Luxembourgish priest. Father Perrault governs Shangri-La from a lamasery of almost obscene opulence (imagine – green bathtubs!). The guests are tastefully divided in their credulity about whether the society is an illusion and the book was devoured by an escapist West suffering the Great Depression.

Rifling my free copy in Hong Kong, I judged it the Englishman’s analogue to the continental cults whose glorious living and glorious dead are distanced by a Napoleonic boulevard of culture and commerce where the stick and carrot are applied. It seemed fortunate that the British are only really any good at stoking a frisson for utopian demise and, as the distant red flags fluttered and my Mao-faced banknotes smirked at me from their money clip, I designated Lost Horizon – and all this – to a fantastic past which would be swept away by Western humility and moderation.

I was wrong and, what is more, I’m glad I was wrong.

Since the collapse of any credible European adversary, Britain has turned inwards in its quest for maudlin schadenfreude. Our woke egalitarianism means everyone must de-mask or debunk any superiority as somehow an act.

I hazily recall a heavy session at the London Ritz at which the bar-chef challenged me to draw my sgian-dubh to establish whether I was carrying an offensive weapon. I was quick-witted enough to reveal my purist stand on another wager of the kilted gentleman which duly precipitated a less troublesome ejection from the premises. But how did we sink to this? Is there anywhere outside of the glittering palaces of sinister dictatorships where a man can live honestly without some spiv trying to trip him up?

More poignantly, perhaps, how can the professionals themselves avoid clientele who know their own job from experience and think they have ‘made it’ because they bussed tables in their student days?

Lost Horizon has at its heart a provocation to serve which the maladjusted West will now struggle to perceive. Utopia should be viewed not as a deception but rather the absence of the contempt for the familiar. The point of Shangri-La is that it was built by strangers in exotic lands for strangers in exotic lands. Lo-Tsen, for whom the valley was home, is repelled by its treasures and risks her life in order to leave. Hugh Conway – the knackered British diplomat at the centre of the novel – appears to have risked his life in order to return, inspiring the enchanted discussion among pilots which opens the book on the darkening concourse of Templehof airport in 1933.

Like the bedraggled Conway, we must keep our eyes fixed on utopia so that our journey becomes a pilgrimage with a view to one day opening the doors of our own Shangri-La.

And so much for the better if nobody follows.

Understanding Undset

Sigrid Undset’s is doubtlessly among the twentieth century’s greatest writers, even though Kristin Lavransdatter, her main works of literature, is set in the fourteenth century. At the ceremony awarding Undset the 1928 Nobel Prize for Literature, Per Hallström described the writer’s narrative as “vigorous, sweeping, and at times heavy”:

It rolls on like a river, ceaselessly receiving new tributaries whose course the author also describes, at the risk of overtaxing the reader’s memory. […] And the vast river, whose course is difficult to embrace comprehensively, rolls its powerful waves which carry along the reader, plunged into a sort of torpor. But the roaring of its waters has the eternal freshness of nature. In the rapids and in the falls, the reader finds the enchantment which emanates from the power of the elements, as in the vast mirror of the lakes he notices a reflection of immensity, with the vision there of all possible greatness in human nature. Then, when the river reaches the sea, when Kristin Lavransdatter has fought to the end the battle of her life, no one complains of the length of the course which accumulated so overwhelming a depth and profundity in her destiny. In the poetry of all times, there are few scenes of comparable excellence.

Obviously Kristin Lavransdatter must be read for itself. I started reading it in the Stellenbosch University library a decade ago and was able to finish it thanks to being given a copy by a kindly Premonstratensian.

But the woman behind Kristin wrote more: her biographical essays and other works (like the one describing a visit to Glastonbury) are just as enjoyable and insightful.

At First Things, Elizabeth Scalia describes Undset’s lives of saints and holy men and women in Sigrid Undset’s Essays for Our Time.

Stephen Sparrow reveals much of Undset’s own biographical detail and how this influenced her writing in Sigrid Undset: Catholic Viking.

But the best essay I’ve read on Sigrid Undset so far is David Warren’s meditation on womanhood, motherhood, and Kristin Lavransdatter. I don’t agree with everything he says (I rather enjoyed the new translation but am thinking I might have to give the old one a go), but David gets Kristin the character, gets Kristin the novel, and gets the way that life is refracted through both.

Read David Warren, then read Sigrid Undset.

The Dawn of Da’esh

Patrick Cockburn, 192 pages, £9.99 (Verso Books, London)

words that flow confidently off the page and exude a sense of first-hand knowledge and on-the-ground insight, it’s easy to see how Patrick Cockburn has attained his reputation amongst those in the know as the foremost and most authoritative Western correspondent in the Middle East today. The Rise of Islamic State: ISIS and the New Sunni Revolution (Verso Books, February 2015) attempts to sketch out the meteoric rise of the soi-disant caliphate’s black-clad gunmen and the factors which have facilitated it. This is no easy task, and while Cockburn does not quite achieve it, his effort is deeply informative—it is hard to imagine anyone could do better than he has in relaying the astounding complexity of the situation in Iraq and Syria today.

words that flow confidently off the page and exude a sense of first-hand knowledge and on-the-ground insight, it’s easy to see how Patrick Cockburn has attained his reputation amongst those in the know as the foremost and most authoritative Western correspondent in the Middle East today. The Rise of Islamic State: ISIS and the New Sunni Revolution (Verso Books, February 2015) attempts to sketch out the meteoric rise of the soi-disant caliphate’s black-clad gunmen and the factors which have facilitated it. This is no easy task, and while Cockburn does not quite achieve it, his effort is deeply informative—it is hard to imagine anyone could do better than he has in relaying the astounding complexity of the situation in Iraq and Syria today.

Much of the novelty of ISIS lies in the suddenness of their appearance and the continuous string of victories they have amassed. Cockburn is quick to point out that much of this is propaganda: ISIS has been a player in the region for years, but mostly as an authorised bin Laden franchise founded by the Jordanian Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and under the name of Al-Qaeda in Iraq. Following al-Zarqawi’s death, the Sunni jihadist group transformed into the Islamic State in Iraq and proclaimed its new leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi the ‘emir’, expanding operations into Syria by 2013.

Despite numerous successful terrorist attacks and assassinations, it is the capture of Mosul in June 2014 which Cockburn singles out as the start of ISIS as the phenomenon we are experiencing today. This stellar rise has yet to prove fully meteoric in the sense that, while their onward march has ground to a halt at Kobane, ISIS has stubbornly refused to burn out and fade away. This has been contingent upon an alignment of factors which might be oversimplified into three: the endemic corruption of the Iraqi state, the astounding stupidity of Western powers, and the entrenched sectarianism of Iraqi society.

As one of the most central institutions of the state, the melting-away of the Iraqi Army’s resistance to ISIS has been crucial. It is difficult to overestimate the vast scale of corruption in the Army. Military units often include large numbers of troops that exist only on paper. Command of a division comes with a high pricetag. Having borrowed the money to pay for it, divisional commanders then require steady income streams to pay back the loan. Setting up roadblocks to extort money from travellers is an easy task for an armed force, but the possibilities are numerous.

A retired Iraqi general tells Cockburn the rot first set in when, in 2005, the Americans demanded the Iraqi Army outsource food and logistical supply:

“A battalion commander was paid for a unit of 600 soldiers, but had only 200 men under arms and pocketed the difference, which meant enormous profits.”

In Mosul, Cockburn points out, only one in three of the soldiers meant to be there were physically present, the rest having payed up to half their salaries to be on permanent leave.

Endemic corruption of this kind has been fostered by the complacency of the governing elite. A Turkish businessman was ruffled when a local ISIS leader demanded $500,000 per month in protection money. “I complained again and again to the government in Baghdad,” he relates to Cockburn, “but they would do nothing about it except to say that I should add the money I paid to al-Qaeda to the contract price.” Such an attitude hardly inspires confidence in the state.

As ISIS gained ground across Iraq, the Baghdad elite seemed only to increase its insularity, acting as if nothing was wrong. “When you speak to any political leader in Baghdad,” an ex-minister says, “they talk as if they had not just lost the country.”

“ISIS,” Cockburn points out, “are experts in fear.” YouTube has been deployed with a methodical exactness towards this end. The talking heads who’ve preached the gospel of new media as breaking down barriers and leading to an immanent global liberation have plainly failed to grasp that these new forms of communication can be expertly employed by forces intrinsically opposed to their vision of a liberal utopia.

While the Shi’ites have long been in the majority, the Sunnis were top-dog under Saddam, widely favoured and occupying places of power and authority. With Saddam toppled and democratic elections now forming the basis of the state’s legitimacy, the numerical strength of the Shia has handed the state to Shi’ite political forces fearful of a return to the old days. When Sunnis complain of violence, intimidation, and discrimination at the hands of the Shia-dominated government in Baghdad, Shi’ites don’t see the Sunnis as reacting to oppression but as plotting a return to their former dominance.

This de-legitimisation of the official state in the eyes of Sunni Iraqis has provided the space in which the zealous ISIS has come to the fore. Where ISIS rules it is widely unpopular – in a country of smokers, Cockburn notes, they have demanded bonfires of cigarettes in captured towns – but too many of ISIS’s enemies are opposed to all Sunnis, not just ISIS. This means Sunnis opposed to ISIS have no one to turn to for protection or support. All too many have calculated that enforced piety and oppression from ISIS are preferable to being murdered by Shia militiamen in police uniforms just for being Sunni.

But one of the most influential factors in the rise of the Islamic State in Iraq has been events in neighbouring Syria. Shifting his aim westwards, Cockburn provides analysis of events that is both illuminating and frustrating. The interference of external powers in Syria, whether Middle-Eastern or Western, has had catastrophic and usually counter-productive effect. In the midst of a supposed ‘global war’ on Islamic terror, the logic of toppling yet another bastion of Ba’athist-style dictatorial secularism in the region is murky. Encouraging a Sunni uprising in Syria without foreseeing a knock-on effect in neighbouring Iraq also strikes Cockburn as particularly naive.

The vitality of continued opposition to Assad by the US-led Western powers and by states in the region is astonishing – almost satanic. The United States happily allied itself with the most murderous force in the twentieth century – the USSR – in order to defeat the more pressing evil of Nazi Germany. And yet the exponentially milder Assad regime is somehow considered totally untouchable – or ‘haram’ as the locals of the region might say. It was only twenty-odd years ago Syrian troops were fighting as part of the US-led coalition in the First Gulf War. The transformation since then is inexplicable (and, with his hands already full, Cockburn does not attempt to offer any insight into this).

Despite the severity of the civil war being waged in Syria, the West has demonstrated openly and brazenly that it is more interested in eliminating Assad than ending the war. As Cockburn frequently points out, Assad has continuously been in control of all but two regional capitals in Syria, yet the United States says he can’t even have a place at the negotiating table unless he agrees to give up power. That’s not a pre-condition: it’s a repudiation. Failed politicians in this part of the world don’t retire to bank boards and book deals like in the West – more often their bloodied corpses are dragged from their palaces by a mob of well-orchestrated ferocity. (The victors’ justice of Saddam’s execution is a rare example that tests the rule.)

Laying the Assad-must-go precondition is a bold statement by Western powers that they grant zero priority to ending the war. Despite all their high-minded liberal humanitarian cover talk, it’s simply not on the agenda: Power is the only thing.

Despite the unsurprisingly depressing subject matter, the author is persuasive in his clear and cogent writing. This book—and Cockburn’s reporting more generally—is helpful both to those with some familiarity with the region and total novices in deepening one’s understanding of a situation that defies adjectives.

As bombs were falling on Libya, Cockburn pointed out the jihadist nature of many of the rebel groups in the north African country, only to be confronted by an American reporter: “Just remember who the good guys are.” For those looking to avoid the Manichean oversimplifications we are too often fed, this book is a welcome and insightful reprieve.

Secret Splendor

by Andrew Cusack (Weekly Standard, 13 September 2010)

Paintings for the Catholic Church in the Dutch Republic

by Xander van Eck

Waanders, 368 pp., $100

This book is the first major overview and exploration of the art of the clandestine Roman Catholic churches in the Netherlands. It is not a study of paintings so much as a history in which art is like the evidence in a detective story, or perhaps even the characters in a play. It might seem extraordinary that there was a place for large-scale Catholic art during the Dutch Republic: Pre-Reformation churches had been confiscated and were being used for Calvinist services, while priests offered the Mass secretly in makeshift accommodations. Eventually a bargain between Dutch Catholics and the civil authorities emerged, trading Catholic nonprovocation in exchange for private toleration of the practice of the faith. Catholics began to purchase properties which, for all outward appearances, maintained the look of ordinary residences but whose interiors were transformed into resplendent chapels and churches.

Xander van Eck provides verbal portraits (often accompanied by contemporaneous painted ones) of several of the important clerics of the Dutch church during this period: Sasbout Vosmeer, the Delft priest influenced by St. Charles Borromeo; Philippus Rovenus, the vicar-apostolic who placed greater emphasis on clandestine parishes having specially dedicated churches, even while they kept an outward unecclesiastical appearance; and Leonardus Marius, the priest who promoted devotion to the 14th-century Eucharistic “Miracle of Amsterdam.” Marius was of such prominence that, after his death, shopkeepers rented out places on their awnings for punters to view his funeral procession. Van Eck includes a handful of amusing asides, such as the expulsion of the Jesuits from the Netherlands as a result of their constant discord with the secular clergy. Mass continued to be offered at the Jesuit church of De Krijtberg in Amsterdam “in the profoundest secrecy” — thus creating a clandestine church within a clandestine church!

The role of the clergy in sustaining the Dutch Church is unsurprising, but it is instructive to learn how instrumental laity were to keeping alive the light of Catholic faith in the Netherlands at the time. Clandestine churches relied on the generosity of Catholic families. Prominent families often provided their own kin as consecrated virgins who brought large dowries into the church, or as priests with suitable inheritances to maintain or endow clandestine parishes. The clandestine church of ’t Hart in Amsterdam, built by the merchant Jan Hartman for his son studying for the priesthood, is still open today as the Amstelkring Museum and Chapel of “Our Lord in the Attic.”

While van Eck explores the extent to which Dutch art from the period followed European norms, an emphasis on the particularity of the art of the clandestine church is to be expected. The sheer volume of art produced during this period — for just three Amsterdam churches alone there were 16 altarpieces — is partly explained by the phenomenon of “rotating altarpieces.” The paintings above the altar would be changed according to the feast or season — a practice sometimes seen in Flanders or parts of Germany but never nearly so widespread as in the Netherlands proper.

Constrained as clandestine churches were on the narrow plots typical of Dutch cities, there was no room for side chapels that might include the large funerary monuments prominent families would construct. This left altarpieces as the most convenient way for munificent Catholics to provide art for their churches: Rotating the altarpieces provided a handy way of displaying numerous commissions rather than just the donation of whoever had been generous most recently, and the themes of these commissions tended to vary in appropriateness to different feasts and seasons.

Some found fault with this method: Jean-Baptiste Descamps, visiting Antwerp in 1769, complained that the most interesting altarpieces were not permanently displayed and were more likely to be damaged in the process of being moved so often.

While the accomplishment and ingenuity of Dutch Catholics in keeping their faith during the Republic was striking, the ill-defined administrative structure of the persecuted church allowed conflicts between clerics to thrive, and doctrinal disputes emerged and festered. The disputes over Jansenism that swept over France and the Netherlands, for example, only exacerbated the administrative problems of the clandestine church. Like their Calvinist compatriots, the Jansenists tended to frown on indulgences, the veneration of saints, recital of the rosary, and private acts of worship, putting greater emphasis on the Scriptures and a more rigorous asceticism. As van Eck points out, this difference in emphasis was not exclusive to the Jansenists, but their novelty (and their heresy) was in preaching the exclusivity of their approach above all others.

Numerous vicars-apostolic had written to Rome arguing for the re-establishment of the episcopacy in the Netherlands to solve the disputes over authority, but their appeals fell on deaf ears. In 1723 a large portion of the Jansenist clergy reinstituted the episcopacy by electing an archbishop of Utrecht from their number — and were subsequently excommunicated, splitting the clandestine church and its clergy in two. (This excommunicated rump united with the opponents of papal infallibility in the following century to form a body that still calls itself the Old Catholic Church.)

When one looks at all this glorious art, not to mention the lives and pious ingenuity of the persecuted, it’s difficult not to feel a little poorer, considering the fruits of our churches in an ostensibly free era. Why does the church today commission painters who are either mediocre or trendy — or both? Artists like Hans Laagland and Leonard Porter show that good art — good liturgical art, even — is possible today, but commissions from the church for traditional artists are sadly few.

Ten Books

Scribbled Notes

Does anyone talk on the phone anymore? Reading a book in which a casual conversation takes place and the main character hangs up the phone, the fact that the author reveals this hanging-up seems surprising. We didn’t need to know it took place over the phone. But it situates the exchange in a concrete reality of sorts.

I never really feel comfortable speaking on such devices, so I only ever speak to people who are far away, pretty much only my parents. Other people use them voluminously, but I only know for certain myself of very few who do. When CSG was alive (and suspicions still linger over the nature of his death), CDL would sometimes spend hours talking to him on the phone, like two old ladies who suffer too many ailments to get out and meet in person. (I’ll concede that they were in different countries.)

I find the very idea revolting. What could one possibly discuss for hours at length down a strange device it’s not even comfortable to handle? My thoughts don’t flow properly over the phone in a way they do naturally face-to-face or via the written word.

I remember Farley’s stories about when he was a correspondent in Rome and — taking no heed of time differences — his editor would phone him up and deliver long screeds which Farley would make a few accommodating noises to then gently place the phone down on his bedside table and let the man carrying on while he gently faded back into the realms of slumber.

Then again the Major sometimes phones during his lunchtime saunter and he usually has information worth sharing or complaints that are satisfying to share, imbued with doom-laden pessimism.

On the whole, then, I am not a telephone enthusiast. Their primary purpose now is of course as smart phones — incredibly useful devices which have lured us into slavery and the impossibility of living without them.

The book I am reading — the one I mentioned earlier — is The Informers by Juan Gabriel Vásquez. I had never read any Colombians — except for Nicolás Gómez Dávila, but as he spoke in aphorisms he is in another category entirely. Colombia is a mysterious realm to me, with only little snippets having ever filtered down to me. When I was a boy, for a year or two we had the daughter of a Colombian senator at our school who taught me the words to ‘La Cucaracha’ but who, out of fear, was always entirely silent on the subject of home; she point blank refused to talk about it. (There were many killings in those days, and I suppose she was abroad for her own safety.)

But the Colombians are by no means an un-literary people — far from it. As someone briefly educated in Argentina it’s sometimes difficult to concede there is any culture in the Americas outside of Argentina, but Colombia’s Gabriel García Márquez is well-known outside his home country. I suppose I will have to read him some day but I decided to start with Vásquez having read a review of one of his more recent books in the Speccie.

Much as one hates to admit that any living writer is worth reading, Vásquez is good, and just a few pages in I got in touch with my old school friend Lucas to tell him I thought he’d like it. Lucas is an Austro-Argentine-Peruvian-Estadounidense living in Guatemala so he gets it, though what he gets is hard to describe. This novel, for example, is not action-driven but primarily from the interior life, which I think is what I mean.

Ever since school days, Lucas has always had a particular genius for over-analysis that I have always criticised him for and do my best not to provoke or indulge in, though this is difficult. Tell him you love the rain. “What? Do you? Wow! But what is it about the rain you love? Is it a primeval force? Is it because we [meaning humanity] are farmers? Well I suppose you’re Irish so you have to love the rain.” (Lucas has always wanted to be Irish.) Thus, having a furiously intensive interior life himself, Lucas might enjoy a novel set primarily (though not entirely) in the interior realm.

Hippo was here the other day in between Rome and Scotland or wherever. (He’s off to Montepulciano for a few weeks, actually.) We had a jolly auld lunch at the Farmers’ Club and discovered over a cigarette and gin-and-tonic aperitif a mutual love for Balzac. Balzac got it — well, not quite, but pretty damned close enough. I am forever reading Balzac, and going on about him to Beatrice who is mostly uninterested (her late father called him “Balls-ache”) though she is perhaps the person with whom I discuss writing most often.

And so, finishing Vásques, I am continuing through Balzac, and others. I am off to the New World later this week, for not terribly long, but I am bringing Gerard Skinner’s book on Father Ignatius Spencer, Barry Hutton’s history of Lisbon, Sandy’s Corduroy Mansions (seeing as I used to live in Pimlico), Lindie Koorts’s biography of DF Malan, and one or two others in the hope of making some progress and being entertained, informed, or enlightened.

We shall see.

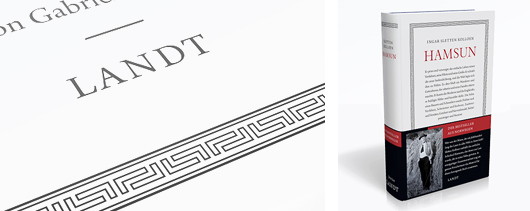

A Handsome Hamsun

Book design is a craft sadly neglected in the English-speaking world. In paperbacks, the French reign supreme, while the Teutons and Scandos design the most elegant hardcover books.

This German edition of Ingar Sletten Kolloen’s biography of Knut Hamsun was designed by Frank Ortmann for Landt Verlag, founded by the conservative popular historian Andreas Krause Landt (aka Andreas Lombard). Landt Verlag is now an imprint of Thomas Hoof’s Manuscriptum publishing firm. Hoof is better known for starting Manufactum, the retail company known for offering high-quality goods made through traditional methods.

I’ve never read any Hamsun myself though he has been strongly recommended by friends with reliable tastes. This Norwegian writer is widely read amongst the Germans but not so amongst the Anglos, and perhaps not surprisingly since he was an uncompromising Anglophobe and had praise for all things German.

Anglophobia was not his worse offence – a Nobel laureate, he ended up giving away the actual medal as a gift to Goebbels – but no less an unquestionable anti-Nazi than Thomas Mann hoped that “the stigma of his politics will one day be separated from his writing, which I regard very highly”.

The designer Frank Ortmann impressed the name of the publisher by incorporating letter-L initials into the rather Hellenic ornamental frame of the book. He’s also managed to banish the dreaded and ubiquitous barcode to a little banderole which also includes a short introductory text, preserving the visual integrity of the book itself.

Voltaire’s Works Are Not Dead

They Are Alive: And They Are Killing Us