About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

UNHQ

United Nations Headquarters, New York

AMONG THE LEGACIES of my New York childhood is a sentimental fondness for the United Nations, and especially for the stylish swank of its headquarters at Turtle Bay in Manhattan. The name of the small neighbourhood originates (scholars tell us) not from the turtles which were once abundant upon the shores of the island and its environs but rather from a small inlet shaped, in the eyes of the old New Netherlanders, like a particular type of bent or curved blade called a deutal knife in Dutch. The woods and meadows surrounding Deutal Bay were easily rechristened as Turtle Bay once the English established their ascendancy and New Amsterdam became New York.

Over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the tiny port founded at the bottom tip of Manhattan grew further and further up the island, swallowing up the old colonial villages like Greenwich, Bloemendal, and Haarlem, or farms like Turtle Bay, Inclenberg, and Kip’s Bay, until as today there is just one giant urban mass stretching from the Battery at the bottom tip of the island all the way to Spuyten Duyvil at the top.

While New Yorkers like to think that there is no possible competitor to the city’s status as capital of the world, there was of course a great debate over where the United Nations should be based. Geneva was an obvious candidate, as the beautiful art-deco Palais des Nations provided a ready-made home for an international organisation. The fathers of the UN, however, did not want to associate themselves so closely with the failure of the old League of Nations the Palais was built for, and so the Geneva option was nixed.

Given the shifting balance of world power, it was thought a New World site might be a wiser choice than a European location. Quebec, as I have written previously, was an obvious possibility as the city is a beautiful melange of Old World and New, and for Europeans was easily accessible by passenger liner. Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific states, however, were in favour of San Francisco for geographic reasons to their obvious benefit, and cited the Californian city’s hosting the 1945 Conference on International Organisation which brought forth the UN Charter.

Fears that the United States would refuse to participate fully in the UN (as with the League of Nations of old) almost guaranteed that the US permanently hosting the world body in order to solidify American resolve in the UN’s favour, but the squabble over precisely where dragged on. The Rockefeller family intervened by offering to the fledgling United Nations Organisation, at no cost whatsoever, a large riparian site at Turtle Bay on the banks of the East River, largely consisting of slaughterhouses at the time. Settled then, but what would the complex look like?

The UN commissioned an international panel of architects chaired by America’s own Walter Harrison (the Rockefeller family’s house architect, as it happened) which among others included Le Corbusier, Oscar Niemeyer, and Sven Markelius. With eleven different architects from eleven different countries — Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Uruguay — one can imagine the squabbling that erupted. Eventually Harrison adjudicated between two overarching concepts, one by Le Corbusier and the other by Niemeyer. The strong, heavy block of Le Corbusier’s Secretariat tower was balanced by the smooth, sweeping lines of Niemeyer’s General Assembly building.

Construction began in 1948 and the United Nations Headquarters opened for business in 1952, with its promenade of poles flying the flag of each of the organisation’s member states — it seemed a new pole went up every week in the early 1990s when geopolitical turmoil added to the number of countries in the world.

The interiors have only been altered slightly here and there over the decades — after all, any change would require a broad agreement from a wide variety of countries. This means that a clean and crisp 1950s modernism has prevailed overall, alas partly undone by recent updates.

I’ll be the first to admit renovation was much needed — some of the Secretariat offices were bordering on the decrepit — but renovations in the public areas have unfortunately seen the interpolation of cheaper furniture of a more recent vintage that fails to fit in with the building’s aesthetic.

Even with this reservation, most of the refit has been a restoration not a redesign, and the building harks back to the 1950s — New York’s last glorious decade when high culture and stylistic excellence matched, before the decades-long crime-ridden descent into dystopia and the following the Giuliani renaissance (itself a dead-cat-bounce, in my opinion).

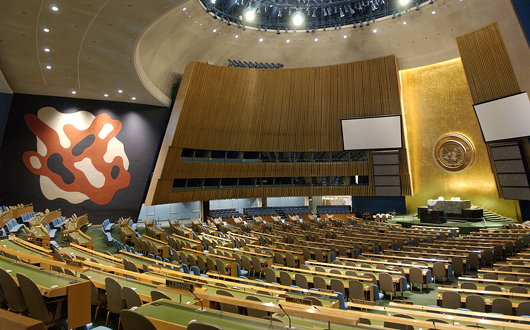

My favourite room in the whole complex is undoubtedly the most important: the General Assembly chamber. A mere glance is enough to confirm the hand of Brazil’s Oscar Niemeyer, and the Assembly chamber is to my mind a much finer design than his later plenary chambers for the national legislature at Brasilia.

The massive emblem surrounded by gold behind the presidential dais has become iconic, as seen here with India’s Nehru addressing the General Assembly. Originally the coats of arms or emblems of the 51 member states were to sit ensconced in circles behind the giant globe-and-laurels, but it was soon envisaged that the prospective expansion of UN membership would make this cumbersome to keep up to date, and so much more suitably we have the sharp simple gold instead.

Some years ago I was meeting Álvaro de Soto (at the time an Under-Secretary General of the UN) for lunch at the Delegates Dining Room and he had one of the guards let us in to the empty General Assembly chamber beforehand for a proper wander round. Sitting down in one of the seats reserved for the United Republic of Tanzania, the country whose deftly chosen official name allows it to sit in between the United Kingdom and the United States of America and overhear all the juiciest gossip, I gave a friendly glance to the separate section on the right where such friendly observers as the Holy See and the Order of Malta have their seats.

The Trusteeship Council chamber formerly hosted meetings of the UN body devoted to decolonisation but as just about every colony worldwide has either achieved independence or enjoys self-government, the Council has fallen into abeyance. (Its abolition, however, would require too complicated a procedure, so it still exists, albeit only with a President and Vice-President for official purposes.) The room was designed by the Danish architect Finn Juhl, and Queen Margrethe II paid a visit during the recent three-year restoration to inspect progress.

The Security Council chamber was donated by Norway and designed by their own Arnstein Arneberg. Their are vast windows on either side of the familiar central mural which let in natural light, but unfortunately the massive curtains tend to be drawn even for the Security Council’s daytime sittings, which gives the chamber a dark and secretive feel.

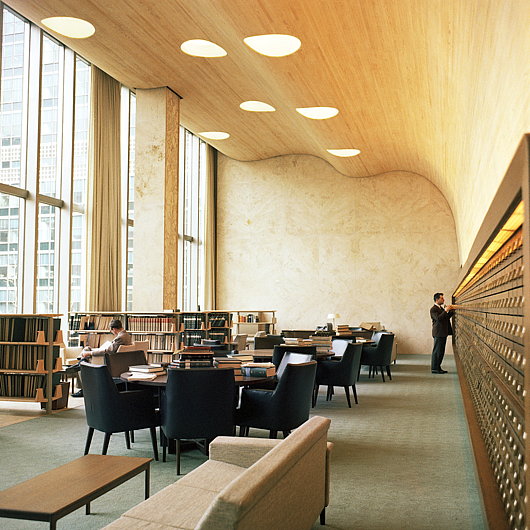

Denmark… Norway… the Scandinavian influence on UN Headquarters is completed by the library named after Sweden’s Dag Hammarskjöld, who died in a plane crash near Ndola, Northern Rhodesia while serving as Secretary-General. Hammarskjöld was influential in securing resources for the United Nations International Library, and it was renamed for him when the addition housing it was officially opened a month after his death in 1961.

Over the years, member states have donated various items and works of art, such as the tapestry above given by the Islamic Republic of Iran. The United States has two works of art at the UN headquarters, both of which are connected to my old school, Thornton-Donovan in the Huguenot city of New Rochelle.

The first is ‘The Golden Rule’, a mosaic by the popular illustrator and artist Norman Rockwell. The earlier part of the artist’s career was spent in New Rochelle, and Rockwell supposedly used children from our small private school as models for his preliminary studies for the mosaic.

The other American artwork at the UN is the mural ‘Titans’ by Lumen Martin Winter, whose home and studio have since been incorporated into Thornton-Donovan’s leafy campus. I remember as a boy at school wandering through the cellar of the late artist’s former house, foraging through sketches, models for bas-reliefs, and other such accoutrements — a study for Winter’s modern crucifixion scene was particularly arresting.

Which brings us to the most important work of art — for what it signifies — donated as a gift to the United Nations by the Soviet Union in its final days. Created from disused American and Soviet missiles, Zurab Tsereteli’s sculpture ‘Good Defeats Evil’ depicts Saint George slaying the dragon. That the crumbling atheistic state finally identified ‘good’ with the cross of Christ gives the donation an almost Milvian Bridge significance.

Despite the world-changing moment of the Soviet collapse, history (as even Mr Fukuyama now admits) has not ended, and both the United Nations organisation and building will continue to evolve. South Sudan, Montenegro, and East Timor are the most recent additions to the flagpoles along First Avenue, and I dare say there will be additions and subtractions yet to come.

When the UN Headquarters and Lever House (its exact contemporary on Park Avenue) were built they were bright and bold portents of the future contrasting handsomely with the brick and stoneclad buildings that made up the overwhelming preponderance of Manhattan structures at the time. Alas, Lever House and the UNHQ were followed by a thousand cheap and poor imitations so that the isle is awash with boring and tawdry glass-plated towers, which lessens the impact of these stately modernist numbers.

But for all these foibles, the UNHQ still exudes a certain 1950s swank that continues to endear, and serves as a welcome reminder of the swansong decade of the capital of the world.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

Riparian shades of Mrs Bucket

It almost sounds as if Mr Cusack is getting homesick.

Is a return to New York from the disdainful shores of an about to be Marxified Britain in the offing?

Not a chance in hell!

Marxified Britain is infinitely preferable to America, which is the actual realisation of the permanent revolutionary regime to an extent to which the Marxists can but dream in envy!

Glad to have got a rise out of you.

But just wait and see, my boy, just wait and see. Perhaps in the end the country of my paternal ancestors will take you in.

This nice piece on the UN with all those pictures brings back a lot of happy memories for me. My mother was an interpreter there and I visited very often as a child. Before all the terrorism of the 80s and 90s and 9/11,I used to be able to wander everywhere there wasn’t a meeting going on, so these buildings were old friends

that omelet painting in the GA :)