2023 December

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Regnum, Ecclesia, Studium

The threefold division of the world

As such he might be expected to have ideas about the idea of a university, and he wrote about them in The Spectator in August 1983.

Mister Grimond (as he still was then, only just), suggested those interested in the subject “might turn to a lecture by Ronald Cant, sometime Reader in Scottish History in the University of St Andrews”:

[…]

A vital aspect of this tripartite organisation, as Cant says, was that each should serve and support the other. But the studium, while interacting with the regnum and ecclesia, must maintain its independence.

It was certainly the business of the studium to advance knowledge, but that was not to be the end of the matter. Knowledge was linked to public service. The learned man had a duty to the community as well as a right to pursue his intellectual quarry. In fact he pursued the quarry on behalf of the community.

The tripartite division of the world, although old-fashioned, seems to me a useful concept, emphasising that government, morality, and higher education are separate but intertwined.

It seems to me that if we expel the regnum and the ecclesia utterly from the world of the university we shall end up paradoxically with universities totally dependent upon the state… but as subservient as those in Rome.

The liberal spirit gave birth and sustenance to universities; if its progeny does not foster it in the regnum they may indeed end up as purely vocational colleges.

Unfinished Business at Audubon Terrace

One of the little tragedies of New York urbanism is that when Archer Milton Huntington was transforming a block of upper Manhattan into an acropolis of culture he failed to buy the entire block.

Huntington named his complex Audubon Terrace in honour of the artist and ornithologist John James Audubon whose home, Minniesland, overlooked the Hudson at the western end of the block. His failure to obtain Minniesland meant that the remainder of the block was snapped up by developers instead of incorporated into his campus.

In the 1910s, the speculators built apartment buildings that turned their rather rude and unadorned backs to Audubon Terrace, terminating the vista from Broadway. When you imagine the potential prospect all the way to the river, it is all the more tragic.

The crass posterior of these apartment blocks naturally dissatisfied the members of the American Academy of Arts & Letters, whose building sits on either side — and indeed beneath — the part of the terrace immediately adjacent to them.

McKim Mead & White had designed the first phase of the Academy’s handsome building facing on to West 155th Street, which opened in 1923, and Cass Gilbert was chosen to design the auditorium and pavilion which would complete the body’s portion of the site.

The Academy used the pavilion for art exhibitions and other events, with the terrace in between serving as a useful spot for springtime drinks parties for the academicians and their many guests.

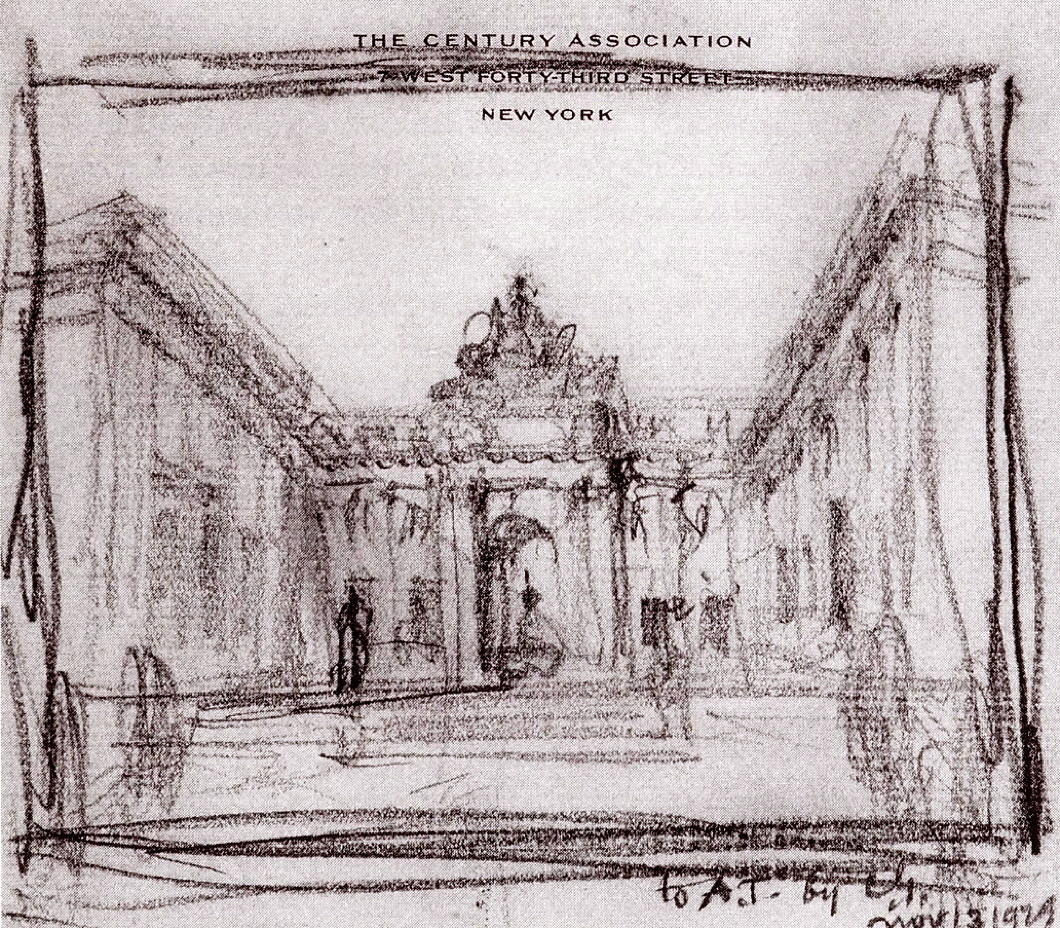

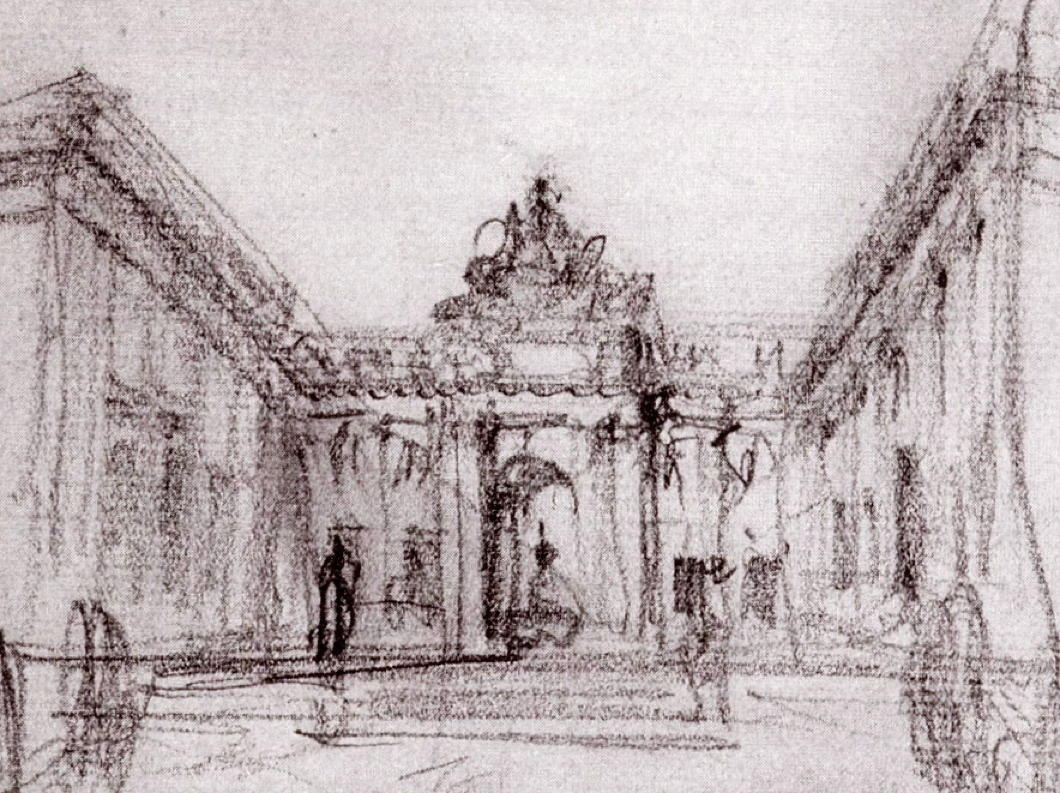

The infelicitous nature of their neighbours clearly irritated the Academy, and in 1929 they had a conversation with Cass Gilbert about designing some sort of screen to satisfyingly terminate the vista down Audubon Terrace and block the view of the apartment buildings.

Gilbert sketched out a plan to build an arched screen connecting the pavilion to the main building across the terrace, topped off by a sculptural flourish.

There is a danger its scale may have overwhelmed the space, but that seems a preferable struggle to face when compared to the problem of the rude neighbours.

Events, as they so often do, intervened. The Wall Street Crash badly affected the American Academy’s finances, and Archer Huntington was forced to increase his already generous subsidy to the body even more just to make ends meet.

Gilbert’s final completion of Audubon Terrace was not to be.

The Academy was founded as a bastion of the old guard against the avante-garde, but in recent decades it has let its hair down a little, and leans more towards the modern than the traditional.

All the same, its current president is an English-public-school-and-Cambridge-educated philosopher from one of the most aristocratic families in Ghana, so it’s reassuring they’re keeping a bit of the old with the new.

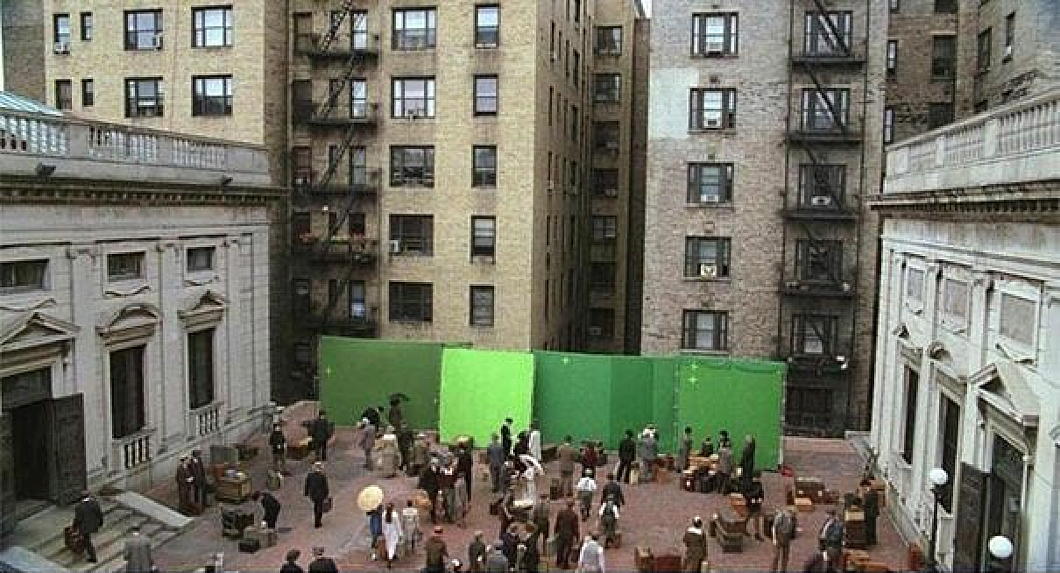

The terrace is often used as a filming location for cinema and television, given the high quality of its architecture and the fact that it is visually not well-known even among New Yorkers, so can be deployed as a foreign setting.

The HBO programme ‘Boardwalk Empire’ used the American Academy’s terrace as an Italian port, using green screens (instead of a Cass Gilbert monumental arch) to transform the piazza.

Audubon Terrace and its surviving institutions — the expanding and renovating Hispanic Society, the American Academy of Arts & Letters, and the Church of Our Lady of Esperanza — are an intriguing hidden gem of upper Manhattan, well worth a visit.

I don’t imagine anything like Cass Gilbert’s screen will ever be built, but every time I drop in to this neck of the woods I can’t help but thinking there’s some unfinished business.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories