About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The Sultan Nazrin Shah Centre

Níall McLaughlin Architects at Worcester College, Oxford

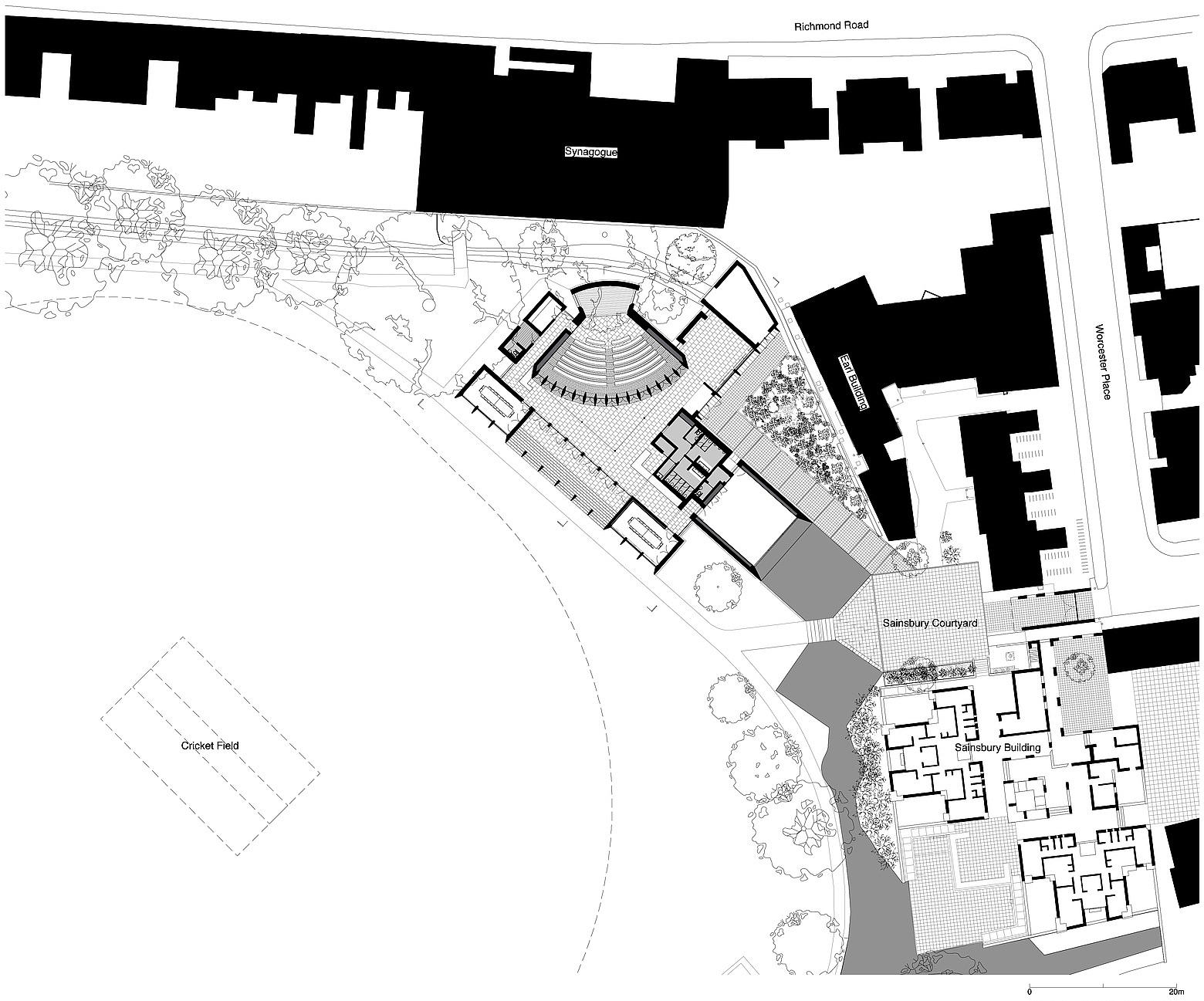

WORCESTER is one of the most spacious and scenic of Oxford’s colleges. The classical symmetry of its entrance terminates the view down the gentle curve of Beaumont Street from the Ashmolean Museum. The twenty-six acres of its grounds are pastoral, with lake, gardens, and the broad expanse of a cricket pitch.

Craftily inserted into this arcadia is the Sultan Nazrin Shah Centre designed by Níall McLaughlin Architects. Collegiate work is familiar to this firm, whose new library at Magdalene College, Cambridge, has won them this year’s Stirling Prize, and the Shah Centre provides new useful facilities for the college without giving it the middle finger.

It is named in gratitude to the generosity of an old boy of the college, HRH Nazrin Ali Shah of Perak, who delights in the title of Sultan, Sovereign Ruler, and Head of the Government of Perak, the Abode of Grace, and its dependencies. Judging by the outcome — itself shortlisted for a Stirling Prize in 2018 — I think he spent his money well.

Tempting though it might be to have a gentle wander through the grounds of the college first, the Shah Centre is best approached through the humble entrance lodge nestled in the corner of the L-shaped Worcester Place north of the college.

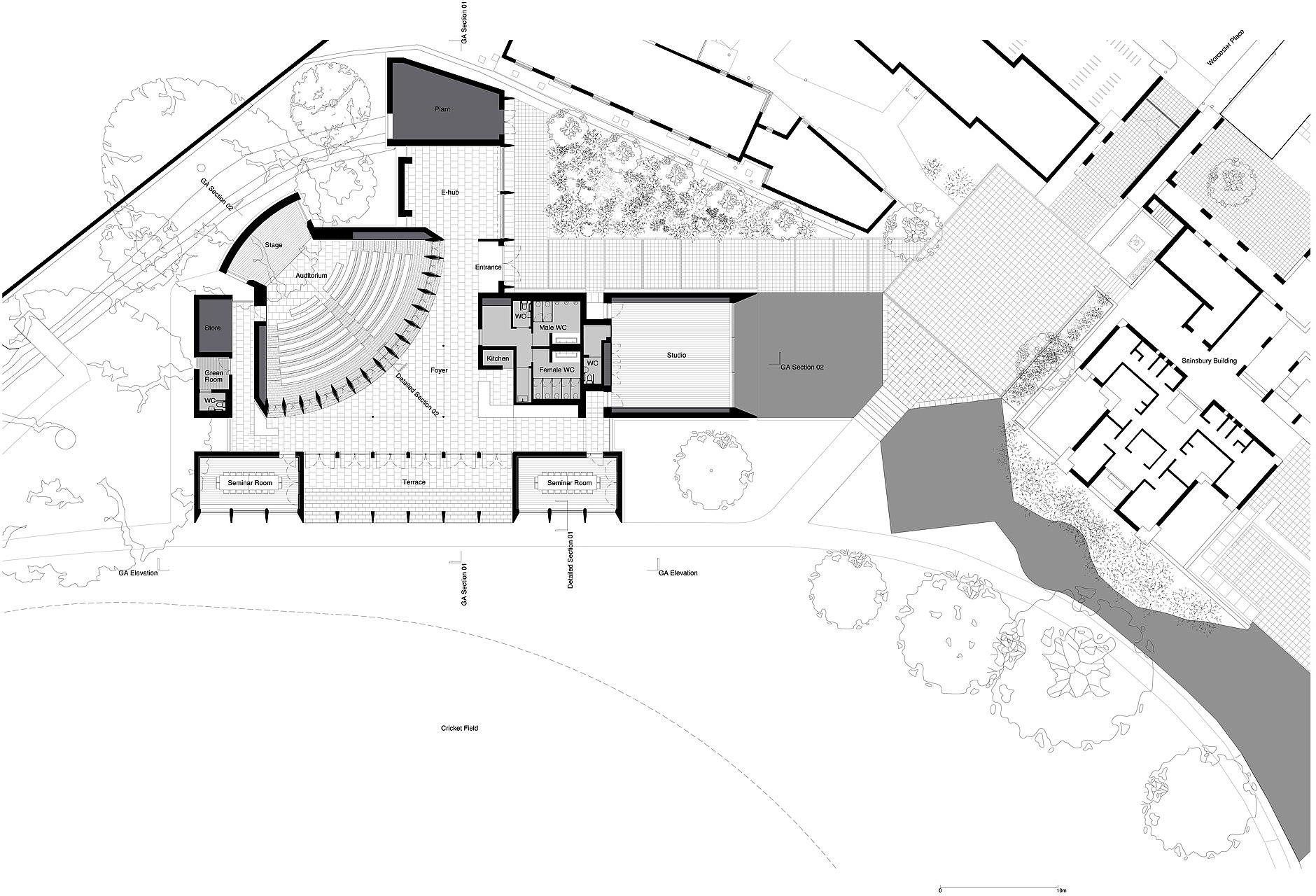

You are led to a little piazza — the Sainsbury Courtyard — framed by a pair of just-below-foot-level diamond-shaped shallow ponds of Kahn-ian geometry. (They are actually a tiny extension of the college lake.) The broad expanse of cricket pitch beyond, connected by a flat wooden bridge segmenting the two diamond ponds, is alluring. But off at a 45-degree-angle on the right, the entrance to the Shah Centre bids the visitor on.

Beyond the limestone cladding you move indoors to a sea of light-treated oak, in the thin supporting columns of the one-storey entrance hall curving around the arc of the lecture theatre and in the trelliswork ceiling.

To the left, the dance studio looks out onto the pools through three giant panes of floor-to-ceiling glass.

To the right, a small bar can double as a registration desk.

The lecture theatre seats 170 and is accessed through a curve of wooden slats that hide panels that can swing out if closing the space is necessary.

Auditoria with ceilings sloping down toward the stage usually feel cramped but here the ceiling is arranged in sharp corrugations (like the flanges of the Gonbad-e Qabus) which capture the light from the clerestory behind.

The feeling is one of spaciousness: rather than facing downwards they are like rays of the sun reaching outwards and up. Instead of wings offstage, there are tall windows of a single sheet of glass flanking, offering natural side light.

The view from the stage is even better, looking out at the gentle curve of clear windows breaking at near-half-way, dividing the anterior spaces below from the open skies above.

Straight out from the auditorium is the terrace with its steps flowing gently down to the field beyond.

It is from the cricket ground that we get the best view of the Shah Centre. The lines are elegant, and there’s a hint of the better architects from Italy’s fascist era — Pagano or Terragni, not Piacentini. The easy movement of space and light, with a gentle breeze rolling off the green.

The architectural genius of the Oxford college as a type is that it allows for the magnificent to be completed on a humane scale for an intimate community of students, scholars, and academics. Níall McLoughlin’s skill at achieving this in a modern idiom is what makes the accolades he accrues — fickle gifts at the best of times — so justified in his case.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Articles of Note: 27 January 2025 January 27, 2025

- Spooks’ Crown January 23, 2025

- Jesuit Gothic January 23, 2025

- Christ Church December 29, 2024

- A Christmas Gift from the Governor December 24, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories