2022 November

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

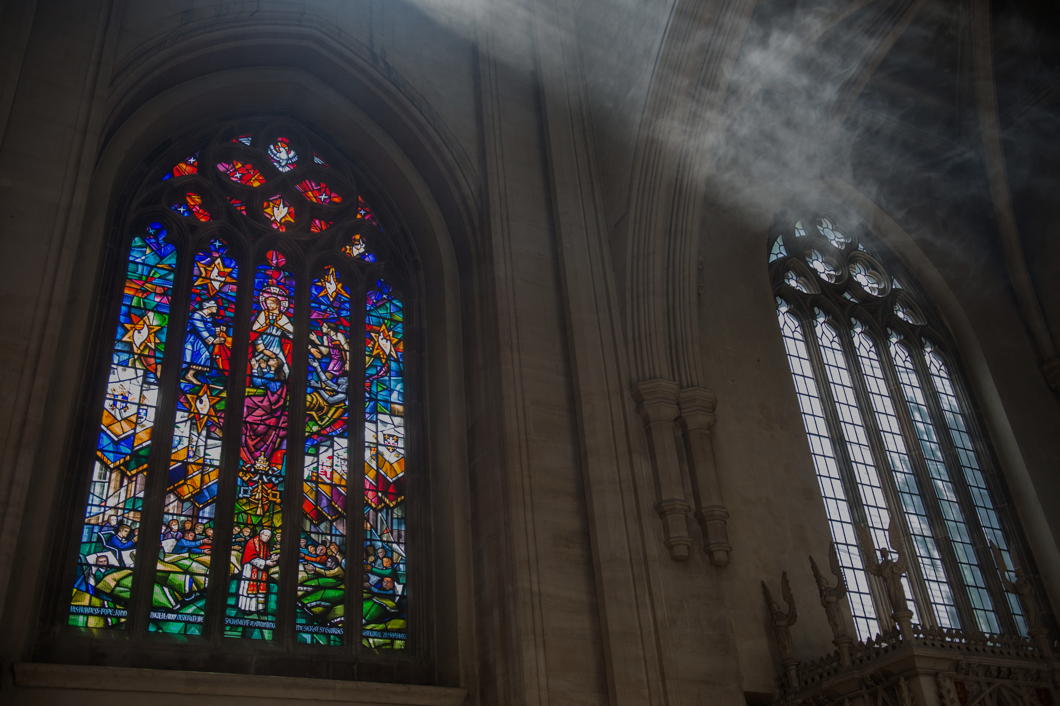

Advent Missa Cantata at St George’s

St George’s Cathedral

Lambeth Road, Southwark, London SE1 6HR

LAMBETH NORTH (Bakerloo)

ELEPHANT & CASTLE (Northern, Bakerloo)

Buses: C10, 360, 12, 453, 138, 53

A collection will be taken to defray the costs.

The Lady Chapel is to the right at the end of the north aisle of the Cathedral (on your right as you enter).

Earlier in the morning, as every Saturday at St George’s Cathedral, there will be Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament from 10:00 to 11:00 am, during which time Confessions will be heard.

Fire the Architects!

Good news everyone! We can fire the architects! That much-hated subset of humanity who have inflicted banality and cheap unpleasantness on the rest of us for nearly a century can finally be chucked into the dustbin of history.

As Nikos Salingaros reports in The Critic, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is revealing what experts deny, exposing the stubborn ignorance of the architectural profession.

Basically, humans don’t like bad architecture because it often communicates psychological threat, like the looming cantilevers that human brains subconsciously have difficulty making sense out of. The body then converts the psychological threat into stress as a defence mechanism, which only works if we in turn avoid bad architecture.

As Christopher Alexander and others have noticed, the key to good architecture is not a specific style but the patterns to which humans respond positively. While trained/brainwashed architects continue to feed us mush and gruel, Artificial Intelligence might be able to step in and provide us the good architecture we not only want, but need as human beings.

Inspired by this theory, I decided to use OpenAI research lab’s DALL-E platform which uses verbal descriptions and transforms them into digital images. E.g. if you put in ‘teddy bear waving a French flag’ it transforms it into an image of a teddy bear waving a French flag.

That might not seem so remarkable when you’re dealing with teddy bears, but when you feed architectural prompts into DALL-E, it delivers the goods.

My favourite architectural style is the Cape Dutch, and my favourite town is Oxford, so I decided to feed this combination into DALL-E by prompting it to give me Oxford colleges designed in a Cape Dutch style.

The results are pretty impressive — OK, to me at least — and below are about two dozen examples.

Not a single one of these buildings exists, but AI takes the parameters of what it ‘knows’ an Oxford college looks like and what it ‘knows’ the Cape Dutch architectural style is, and combines them pretty effectively.

Look at these examples and ask yourself this: would you rather live/work/study in these AI-‘designed’ buildings or in the architect-designed ‘Maison du Savoir’ in Luxembourg?

The reason why architecture is the most influential — and most oppressive — of the arts is that we effectively cannot escape it. Modern man has precious little choice over the architecture of his workplace or place of study, and increasingly less and less control over where he lives.

Too often we are condemned to spend most of our existence in bad architecture, which the body continues to convert into prolonged, low-key stress. The effects on human health, psychology, and general well-being are predictable.

Bad architecture is ultimately the fault of the innumerable powers — house builders, property developers, city councils, and other institutions — who tolerate it. Even if we don’t fire the architects just yet, we can taunt them endlessly and mercilessly by pointing out a machine can design more enjoyable and more humane buildings than they can.

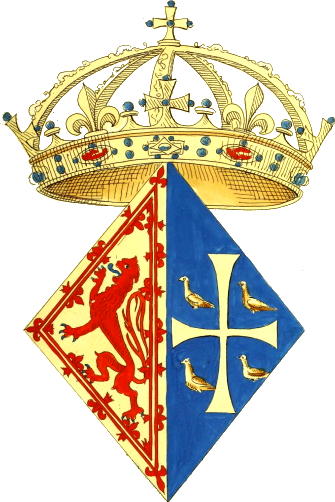

St Margaret Relic Heads to St Andrews

Students from St Andrews University have accompanied their Catholic chaplain to receive a relic of St Margaret of Scotland from the Archbishop of St Andrews & Edinburgh, Dr Leo Cushley.

The relic was put in the care of Canmore, the Catholic chaplaincy at St Andrews, whose chapel is dedicated to the Hungary-born English princess who became Scotland’s saintly queen.

When the relic in St Margaret’s Church in Dunfermline — the country’s royal centre in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries — were being removed from their reliquary the piece of bone fragmented.

The Archdiocese decided to make this an opportunity for the relics of the royal saint to be distributed further.

This relic of St Margaret will remain in Canmore where it will be available for veneration by students and other visitors.

SAINT MARGARET

QUEEN OF SCOTLAND

pray for us

Ödön von Horváth

When the shop purveying diacritical marks opened one morning in Vienna, in my mind the writer Ödön von Horváth turned up and said “Thanks. I’ll have the lot.”

It wasn’t even his real name, of course — which was Edmund Josef von Horváth. A child of the twentieth century, von Horváth was born in Fiume/Rijeka in 1901. His father was a Hungarian from Slavonia (in today’s Croatia) who entered the imperial diplomatic service of Austria-Hungary and was ennobled, earning his “von”.

“If you ask me what is my native land,” von Horváth said, “I answer: I was born in Fiume, grew up in Belgrade, Budapest, Preßburg, Vienna, and Munich, and I have a Hungarian passport.”

“But homeland? I know it not. I’m a typical Austro-Hungarian mixture: at once Magyar, Croatian, German, and Czech; my name is Hungarian, my mother tongue is German.”

From 1908 his primary education was in Budapest in the Hungarian language, until 1913 when he switched to instruction in German at schools in Preßburg (Bratislava) and Vienna.

Von Horváth went off to Munich for university studies — where he began writing in earnest — but quit midway through and moved to Berlin.

He once told his friends the story of when he was climbing in the Alps and stumbled upon the remains of a man long dead but with his knapsack intact.

Intrigued, he opened the knapsack and found an unsent postcard upon which the deceased had written “Having a wonderful time”.

“What did you do with it?” his friends naturally inquired. “I posted it!” was von Horváth’s reply.

In 1931 he was awarded the Kleist Prize for literature, but two years later the National Socialists took the helm and von Horváth thought it best to move across the border to his old imperial capital of Vienna.

Despite his anti-nationalism, he did initially join the guild for German writers set up by the Nazis, possibly to keep his works in print in the Reich while he was living in still-independent Austria.

It was in Vienna he published his best-known work: Jugend ohne Gott — “Youth without God” (first translated into English as The Age of the Fish), which marked his public point-of-no-return break with the Hitlerites.

The novel depicts a jaded schoolteacher increasingly disconnected from his profession and the world around him as the ideology of National Socialism begins to take root in the education system. (Bizarrely, it was also scantly used as the basis for a 2017 dystopian thriller.)

When Hitler’s troops marched into Austria the following year, von Horváth fled to Paris.

“I am not so afraid of the Nazis,” he told a friend there one day. “There are worse things one can be afraid of, namely things you are afraid of without knowing why. For instance, I am afraid of streets. Roads can be hostile to you, can destroy you. Streets frighten me.”

Days later, in the middle of a thunderstorm, von Horváth was walking down the Champs-Élysées — the most famous street in Paris — when a flash of lightning struck a tree, felled a branch, and struck the writer dead. He had been on his way to the cinema to see Walt Disney’s ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs’.

Years ago someone recommended The Eternal Philistine: An Edifying Novel in Three Parts to me, but I have to admit I haven’t yet read it, or much else of von Horváth’s work. (He’s on my fiction wish-list though.)

His plays have been revived, too — here in London at the Almeida and the Southwark Playhouse in the past decade or so — and both The Eternal Philistine and Youth Without God are available in English from the estimable Neversink Library imprint of Melville House.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories