About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Weimar’s Black, Red, and Gold

In fact, there was a great deal of overlap between these two sides, and in the most recent Junge Freiheit Dr Karlheinz Weißmann explains how the troubled Weimar Republic made its choice of national symbols.

The colours of the Republic

by Karlheinz Weißmann — Junge Freiheit 18 February 2019

(slapdash unofficial totally unauthorised translation)

At the end of December 1918, Harry Graf Kessler noted confusedly in his diary that supporters of the [liberal republican] German Democratic Party (DDP) had marched through the centre of Berlin, with the “Greater German colours” black-red-gold and singing Der Wacht am Rhein.

In fact, the left-wing liberals were the only political group next to the Völkisch movement who had clung on to the black-red-gold. For both of them, it was about the ideal of an all-German state, including the Austrians. For the Liberals, it also represented the ideals of the revolution of 1848, while for the Völkisch there was the idea that black, red, and gold were the ancient Aryan colours.

During the period of downfall in 1918 it wasn’t the black-red-gold that mattered: it was the red of the socialists. Majority and Independent Social Democrats as well as the Communists all used it as a symbol. Red armbands, red cockades, and red flags marked the followers of the new republic, whose socialist underpinning was generally believed.

Black-red-gold as last option

By contrast, the old imperial colours of black-white-red almost disappeared. Significantly, the naval mutineers in Kiel had barely raised a hand to defend them. But the soldiers returning home from the front marched under black-white-red flags — which they had made themselves — and were received in the cities, even in Berlin, with black-white-red flags and decorations. The newly established Freikorps also deployed the old imperial colours, as did the cockade of the new Reichswehr whose ranks included many opposed to the republican order.

With this juxtaposition of revolutionary red and the black-white-red of tradition, black-red-gold — Schwarz-Rot-Gold — came as the last option. Some hoped that, on the one hand it would stand for moderation and against total upheaval, while on the other hand it suggested that defeat in the war did not spell the final downfall of the nation.

On 9 November 1918 an organ of the far right, the Alldeutschen Blätter, published an essay entitled “Black-Red-Gold”:

“The birth of Greater Germany is approaching! … Cheer the old black-red-golden colours! Decorate like Vienna your houses with the black-red-golden flags, bows, and bands and show all the world from Aachen and Königsberg to Bozen [Bolzano], Klagenfurt, and Laibach [Ljubljana] that we are a united people of brothers, in no distress of separation or peril.”

Symbol of treason

The 18 February 1919 decision of the State Committee of the Republic to adopt black-red-gold as provisional colours of the Reich was still supported by the expectation that a Greater German Republic would emerge. But the “Anschluss” of Austria was banned at the instigation of the victorious powers and in flagrant contradiction to the right of the self-determination of peoples. This resulted in the first serious discrediting of the black-red-gold.

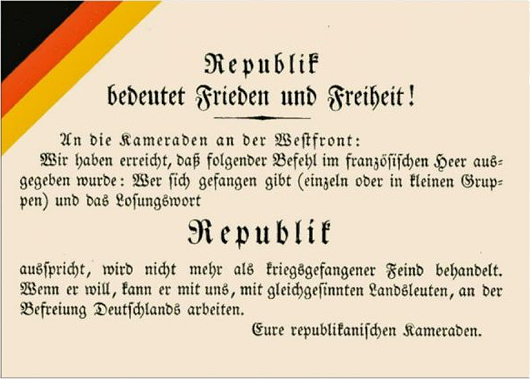

The second was that black, red, and gold had been reputed to be a symbol of treason since the beginning of the war. A group of deserters and pacifists calling themselves the “Friends of the German Republic” — financed with French money and operating from Switzerland — used the colours for their cause as early as 1915, and as early as the spring of 1918 Entente aircraft distributed calls for desertion and revolution along the western front, marked with a black-red-gold stripe or border.

Almost certainly the majority of the population was relieved when, on instructions from the national government, the workers’ and soldiers’ councils adopted the black-red-gold [replacing the red of revolution] but passive acceptance was not enough to give the colour combination permanent support. This was particularly evident in the peculiar “flag compromise” presented by the government with the support of Majority Social Democrats, the Center Party, and part of the DDP during the deliberations of the National Assembly.

According to this compromise, the black-red-gold was introduced as the national flag, while the merchant ensign was the old black, white, and red — albeit with a small black-red-gold flag infelicitously shoved in the canton. Interior Minister Eduard David’s rationale for the choice — that the old colours had been “party” rather than “national” colours — simply did not correspond to fact.

Symbol of Greater Germany

Closer to the truth was the justification that black, red, and gold were the symbols of a Greater Germany. Interior Minister David said:

“What dynastic Germany could not do, democracy must succeed in doing: achieving moral conquests beyond the frontier and, above all, among those who by blood and language belong to us. To win the Greater German unity must now be our goal, not through war and violence, but through the recruiting power of the new republican Germany, and let us fly forward in front of the black-and-red-gold banner!”

In any case, Article 3 of the Weimar Constitution, which entered into force on 11 August 1919, was far from providing a sound answer to the flag question of the young state. As constiutional scholar Ernst-Rudolf Huber wrote:

“This Weimar flag compromise became the cause of endless strife. If the constitutional function of state colours exists in their symbolic power to integrate the state’s unity, the state-sanctioned dualism of contrasting colours manifested in the Weimar flag compromise is a permanent element of disintegration. The flag compromise, with its juxtaposition of the old and new colours, did not diminish the problem of the colour change but rather aggravate it.”

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

- Waarburg October 2, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

Traitors all.

Hoch der Kaiser!