About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

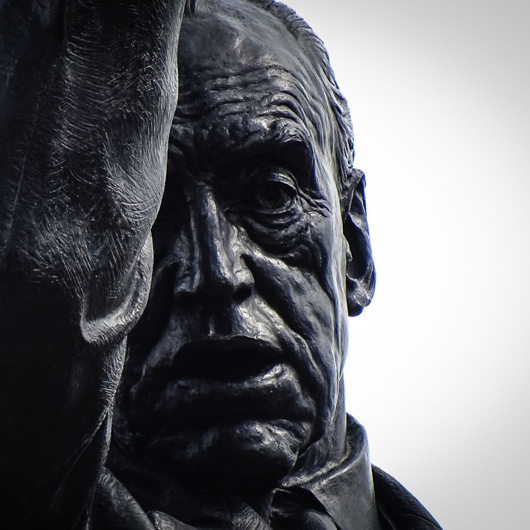

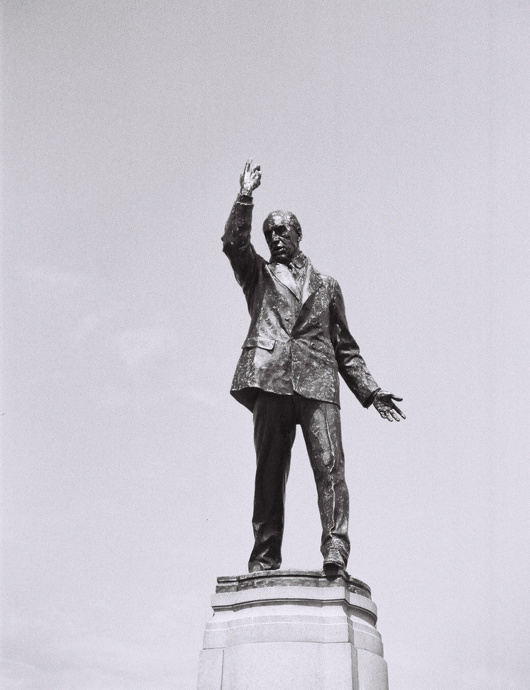

Few statues in Ireland are as dramatic as that of Edward Carson at Stormont. The unionist leader is depicted in amidst an oratorical flourish, doubtless in one of his speeches to mass meetings condemning home rule.

In the 1910s as the rebirth of an Irish parliament looked more likely, Carson took up the cause of fighting home rule on behalf of Ireland’s large Protestant minority who feared Catholic domination. When the anti-home rulers realised the cause was losing, they retreated from Irish unionism to Ulster unionism. If home rule was to be granted, Ulster must be exempted. In the end this meant home rule was granted to a parliament covering two-thirds of the Irish province of Ulster — six counties that would henceforth be known as Northern Ireland.

“His larger than life-size statue,” one historian wrote, “erected in his own lifetime in front of the Northern Ireland parliament at Stormont, symbolizes the widely held perception that Northern Ireland is Carson’s creation.”

This is of course the great irony, given that Edward Carson was a Dublin boy through and through. While instrumental in ensuring northeastern Ireland’s exemption from an Irish parliament, Carson actually had little to do with the entity thereby created. When offered the premiership of Northern Ireland he declined it on the grounds of having no real connection with the place.

Craig, not Carson, is the true father of Northern Ireland; he imbued the new statelet with a sense of bigotry and tribal hatred that Carson lacked. The Dubliner urged Ulster’s new leaders to treat the province’s Catholics well.

“We used to say that we could not trust an Irish parliament in Dublin to do justice to the Protestant minority,” Carson said. “Let us take care that that reproach can no longer be made against your parliament, and from the outset let them see that the Catholic minority have nothing to fear from a Protestant majority.”

Alas, it became apparent to Carson that discrimination and inequality were becoming in-built within Northern Ireland’s government, from the Parliament at Stormont down to the lowest forms of local government. He confided to a Catholic friend in London that rather than being an integral part of the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland was turning into “a second-class dominion”.

After partition Carson was created a British judge and accordingly ennobled. (Disappointingly the plaque on his Dublin birthplace next to Conradh na Gaeilge refers to him by the incorrect style of ‘Lord Edward Carson’.) He settled at Clever Court near Minster-in-Thanet, Kent, and never lived in his native Ireland again.

Nonetheless he was held in awe and reverence by the Protestant Unionists of Ulster, who commissioned the striking statue by Leonard Stanford Merrifield that stands in front of Parliament Buildings, Stormont — now home to the Northern Ireland Assembly. It was unveiled by Craig, by then ennobled as Lord Craigavon, while Carson was alive and present in July 1932, joined by a crowd of 40,000 well-wishers.

Carson died in 1935 and was given the rare honour of a state funeral. HMS Broke brought his Union-Jack-draped coffin back to Ireland — albeit to Belfast — and he was interred in the Anglican Cathedral of St Anne. Northern Ireland claimed him even in his final burial: soil from each of its six counties was scattered on his coffin when laid to rest in the tomb.

Still his statue stands at Stormont, gesturing stridently as if to challenge an entire province — a province he by his own description had little to do with. Calls for it to be removed emanate occasionally from typically boring quarters and have so far been rebuffed — wisely. Carson, unlike many of those who cherished his memory, was an honourable man, and it is a pity it took so long for the Protestants of Ulster to heed the advice of their confrère from Dublin.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

Carson was an outstanding lawyer, and possessed of a fine sense of humor. He is also an outstanding example of the lawyers ruining the deal. His original intent was to keep a united Ireland in the Union, and without Home Rule. Yet, he caused a divided Ireland, the great majority of which is outside the commonwealth, and one where violence dominated politics for generations. He also ensured the destruction of the large Protestant population throughout the South, and particularly in Cork. He ought to have acquiesced in Home Rule, and Ireland would be better for it today. It might even be part of the commonwealth, an increasingly irrelevant institution. The Irony is that the Catholics posed no danger to the Protestants, but the Protestants were determined to oppress the Catholics (which was true in the days of James II, and it remains true today.) He led the faction that unleashed the forces of sectarianism and violence, and led to the the great political reaction known as Irish Republicanism. Perhaps if he had been a solicitor, and not a barrister, he might have been a better advocate for his cause. Sometimes, you need to settle.