2018 December

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Secret Splendor

by Andrew Cusack (Weekly Standard, 13 September 2010)

Paintings for the Catholic Church in the Dutch Republic

by Xander van Eck

Waanders, 368 pp., $100

This book is the first major overview and exploration of the art of the clandestine Roman Catholic churches in the Netherlands. It is not a study of paintings so much as a history in which art is like the evidence in a detective story, or perhaps even the characters in a play. It might seem extraordinary that there was a place for large-scale Catholic art during the Dutch Republic: Pre-Reformation churches had been confiscated and were being used for Calvinist services, while priests offered the Mass secretly in makeshift accommodations. Eventually a bargain between Dutch Catholics and the civil authorities emerged, trading Catholic nonprovocation in exchange for private toleration of the practice of the faith. Catholics began to purchase properties which, for all outward appearances, maintained the look of ordinary residences but whose interiors were transformed into resplendent chapels and churches.

Xander van Eck provides verbal portraits (often accompanied by contemporaneous painted ones) of several of the important clerics of the Dutch church during this period: Sasbout Vosmeer, the Delft priest influenced by St. Charles Borromeo; Philippus Rovenus, the vicar-apostolic who placed greater emphasis on clandestine parishes having specially dedicated churches, even while they kept an outward unecclesiastical appearance; and Leonardus Marius, the priest who promoted devotion to the 14th-century Eucharistic “Miracle of Amsterdam.” Marius was of such prominence that, after his death, shopkeepers rented out places on their awnings for punters to view his funeral procession. Van Eck includes a handful of amusing asides, such as the expulsion of the Jesuits from the Netherlands as a result of their constant discord with the secular clergy. Mass continued to be offered at the Jesuit church of De Krijtberg in Amsterdam “in the profoundest secrecy” — thus creating a clandestine church within a clandestine church!

The role of the clergy in sustaining the Dutch Church is unsurprising, but it is instructive to learn how instrumental laity were to keeping alive the light of Catholic faith in the Netherlands at the time. Clandestine churches relied on the generosity of Catholic families. Prominent families often provided their own kin as consecrated virgins who brought large dowries into the church, or as priests with suitable inheritances to maintain or endow clandestine parishes. The clandestine church of ’t Hart in Amsterdam, built by the merchant Jan Hartman for his son studying for the priesthood, is still open today as the Amstelkring Museum and Chapel of “Our Lord in the Attic.”

While van Eck explores the extent to which Dutch art from the period followed European norms, an emphasis on the particularity of the art of the clandestine church is to be expected. The sheer volume of art produced during this period — for just three Amsterdam churches alone there were 16 altarpieces — is partly explained by the phenomenon of “rotating altarpieces.” The paintings above the altar would be changed according to the feast or season — a practice sometimes seen in Flanders or parts of Germany but never nearly so widespread as in the Netherlands proper.

Constrained as clandestine churches were on the narrow plots typical of Dutch cities, there was no room for side chapels that might include the large funerary monuments prominent families would construct. This left altarpieces as the most convenient way for munificent Catholics to provide art for their churches: Rotating the altarpieces provided a handy way of displaying numerous commissions rather than just the donation of whoever had been generous most recently, and the themes of these commissions tended to vary in appropriateness to different feasts and seasons.

Some found fault with this method: Jean-Baptiste Descamps, visiting Antwerp in 1769, complained that the most interesting altarpieces were not permanently displayed and were more likely to be damaged in the process of being moved so often.

While the accomplishment and ingenuity of Dutch Catholics in keeping their faith during the Republic was striking, the ill-defined administrative structure of the persecuted church allowed conflicts between clerics to thrive, and doctrinal disputes emerged and festered. The disputes over Jansenism that swept over France and the Netherlands, for example, only exacerbated the administrative problems of the clandestine church. Like their Calvinist compatriots, the Jansenists tended to frown on indulgences, the veneration of saints, recital of the rosary, and private acts of worship, putting greater emphasis on the Scriptures and a more rigorous asceticism. As van Eck points out, this difference in emphasis was not exclusive to the Jansenists, but their novelty (and their heresy) was in preaching the exclusivity of their approach above all others.

Numerous vicars-apostolic had written to Rome arguing for the re-establishment of the episcopacy in the Netherlands to solve the disputes over authority, but their appeals fell on deaf ears. In 1723 a large portion of the Jansenist clergy reinstituted the episcopacy by electing an archbishop of Utrecht from their number — and were subsequently excommunicated, splitting the clandestine church and its clergy in two. (This excommunicated rump united with the opponents of papal infallibility in the following century to form a body that still calls itself the Old Catholic Church.)

When one looks at all this glorious art, not to mention the lives and pious ingenuity of the persecuted, it’s difficult not to feel a little poorer, considering the fruits of our churches in an ostensibly free era. Why does the church today commission painters who are either mediocre or trendy — or both? Artists like Hans Laagland and Leonard Porter show that good art — good liturgical art, even — is possible today, but commissions from the church for traditional artists are sadly few.

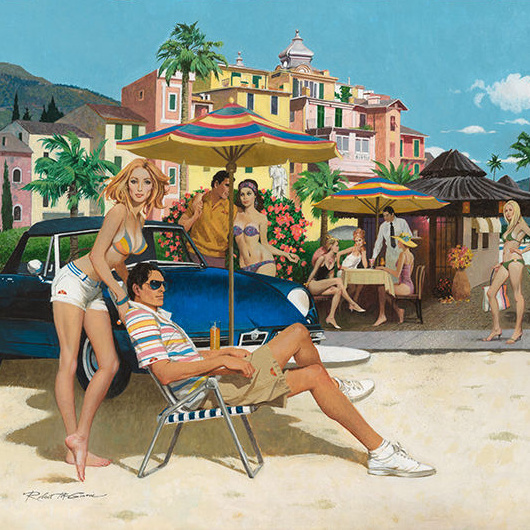

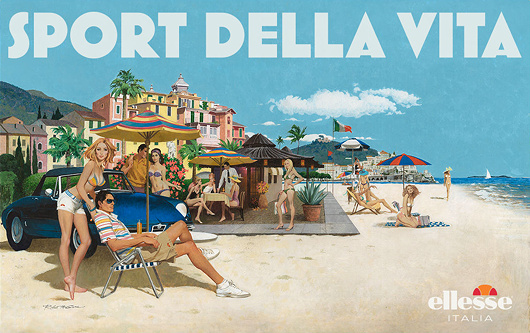

That Sixties/Seventies Style

Robert McGinnis for Ellesse

Italian clothing company Ellesse hired Robert McGinnis — illustrator of over 1,200 paperback covers and several James Bond movie posters — to do four paintings for their 2011 spring/summer advertising campaign.

Ellesse was founded in 1959 by Leonardo Servadio — L.S. — and became known for combining functional sportswear with a sense of fashion. The firm was purchased by Britain’s Pentland Group in 1994, and it’s Pentland’s ad team that commissioned McGinnis to come up with these retro ad designs.

McGinnis’s work here feels strangely up-to-date and yet nostalgic without any particular contradiction. Still, one half expects Sean Connery to strut cheekily into view.

Roots and Permanent Interests

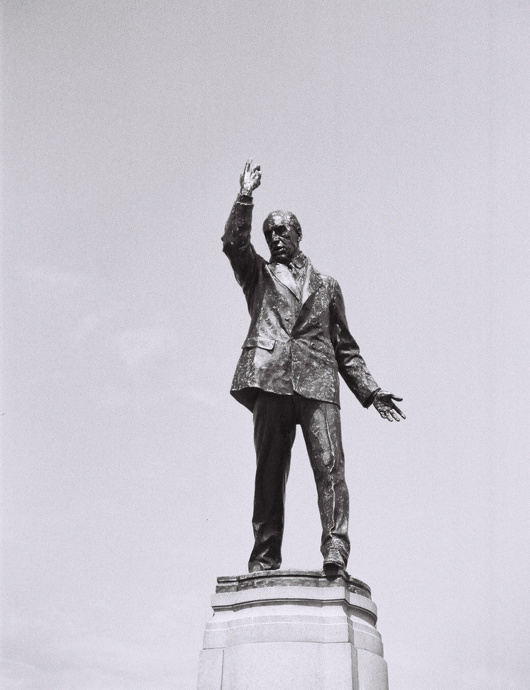

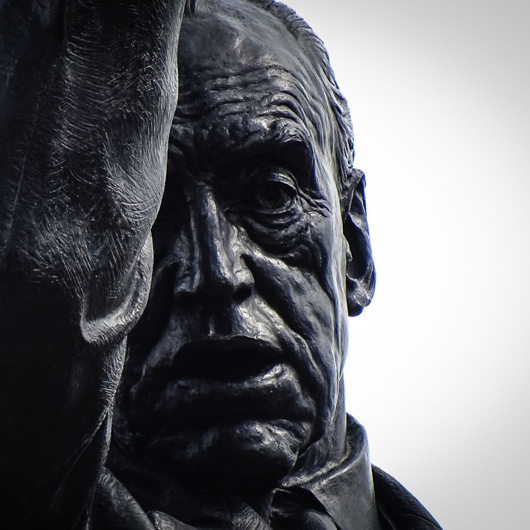

Carson at Stormont

Few statues in Ireland are as dramatic as that of Edward Carson at Stormont. The unionist leader is depicted in amidst an oratorical flourish, doubtless in one of his speeches to mass meetings condemning home rule.

In the 1910s as the rebirth of an Irish parliament looked more likely, Carson took up the cause of fighting home rule on behalf of Ireland’s large Protestant minority who feared Catholic domination. When the anti-home rulers realised the cause was losing, they retreated from Irish unionism to Ulster unionism. If home rule was to be granted, Ulster must be exempted. In the end this meant home rule was granted to a parliament covering two-thirds of the Irish province of Ulster — six counties that would henceforth be known as Northern Ireland.

“His larger than life-size statue,” one historian wrote, “erected in his own lifetime in front of the Northern Ireland parliament at Stormont, symbolizes the widely held perception that Northern Ireland is Carson’s creation.”

This is of course the great irony, given that Edward Carson was a Dublin boy through and through. While instrumental in ensuring northeastern Ireland’s exemption from an Irish parliament, Carson actually had little to do with the entity thereby created. When offered the premiership of Northern Ireland he declined it on the grounds of having no real connection with the place.

Craig, not Carson, is the true father of Northern Ireland; he imbued the new statelet with a sense of bigotry and tribal hatred that Carson lacked. The Dubliner urged Ulster’s new leaders to treat the province’s Catholics well.

“We used to say that we could not trust an Irish parliament in Dublin to do justice to the Protestant minority,” Carson said. “Let us take care that that reproach can no longer be made against your parliament, and from the outset let them see that the Catholic minority have nothing to fear from a Protestant majority.”

Alas, it became apparent to Carson that discrimination and inequality were becoming in-built within Northern Ireland’s government, from the Parliament at Stormont down to the lowest forms of local government. He confided to a Catholic friend in London that rather than being an integral part of the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland was turning into “a second-class dominion”.

After partition Carson was created a British judge and accordingly ennobled. (Disappointingly the plaque on his Dublin birthplace next to Conradh na Gaeilge refers to him by the incorrect style of ‘Lord Edward Carson’.) He settled at Clever Court near Minster-in-Thanet, Kent, and never lived in his native Ireland again.

Nonetheless he was held in awe and reverence by the Protestant Unionists of Ulster, who commissioned the striking statue by Leonard Stanford Merrifield that stands in front of Parliament Buildings, Stormont — now home to the Northern Ireland Assembly. It was unveiled by Craig, by then ennobled as Lord Craigavon, while Carson was alive and present in July 1932, joined by a crowd of 40,000 well-wishers.

Carson died in 1935 and was given the rare honour of a state funeral. HMS Broke brought his Union-Jack-draped coffin back to Ireland — albeit to Belfast — and he was interred in the Anglican Cathedral of St Anne. Northern Ireland claimed him even in his final burial: soil from each of its six counties was scattered on his coffin when laid to rest in the tomb.

Still his statue stands at Stormont, gesturing stridently as if to challenge an entire province — a province he by his own description had little to do with. Calls for it to be removed emanate occasionally from typically boring quarters and have so far been rebuffed — wisely. Carson, unlike many of those who cherished his memory, was an honourable man, and it is a pity it took so long for the Protestants of Ulster to heed the advice of their confrère from Dublin.

St Nicholas, Our Patron

As by now you are all well aware, today is the feast of Saint Nicholas, the patron-saint of New York. His patronship (patroonship?) over the Big Apple and the Empire State date to our Dutch forefathers of old – real founding fathers like Minuit, van Rensselaer, and Stuyvesant, not those troublesome Bostonians and Virginians who started all that revolution business.

Despite being Protestants of the most wicked and foul variety, the New Amsterdammers and Hudson Valley Dutch maintained their pious devotion to the Wonder-working Bishop of Myra and kept his feast with great solemnity.

After New Netherland came into the hands of the British (and was re-named after our last Catholic king) the holiday continued to be celebrated by the Dutch part of the population, and was greatly popularised in the early nineteenth century by the publication of a curious volume entitled A History of New York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty which purported to be by one Diedrich Knickerbocker.

In fact it was by Washington Irving, the first American writer to make a living off his pen, who did much to popularise St Nicholas Day in New York as well as to revive the celebration of Christmas across the young United States.

While, aside from hearing Mass and curling up with a clay pipe and a volume of Irving (being obsessive, I have two complete sets) here are a few links that shed some light on New York’s heavenly protector.

Historical Digression: Santa Claus was Made by Washington Irving

New-York Historical Society Quarterly: Knickerbocker Santa Claus

The History Reader: The 18th Century Politics of Santa Claus in America

The New York Times: How Christmas Became Merry

The Hyphen: Thomas Nast’s Illustrations of Santa Claus

– plus: Santa Claus and the Ladies

National Geographic: From Saint Nicholas to Santa Claus

Previously: Saint Nicholas (Index)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories