About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

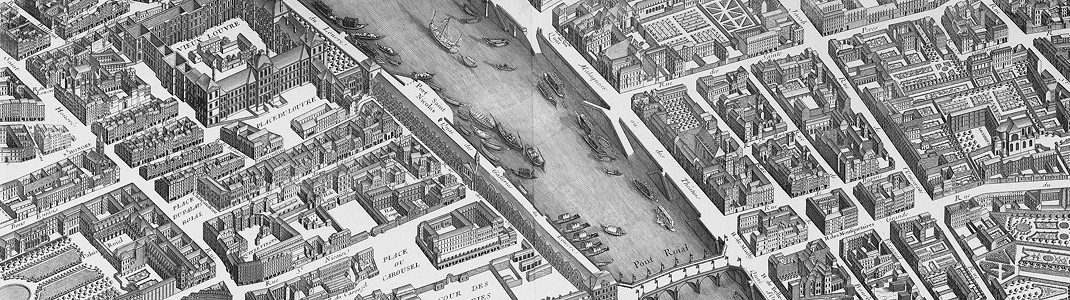

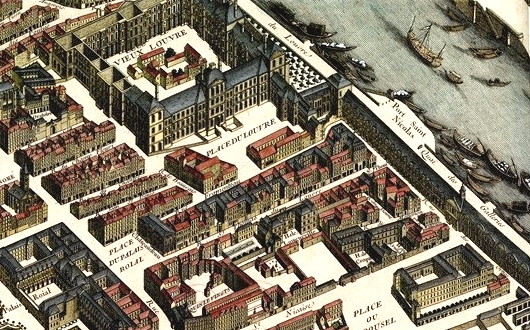

We are so used to the now-familiar image of the palais du Louvre — with its central wing and flanking arms wide open to the Jardin des Tuileries — that it’s easy to forget just how recent a creation this ensemble is. The palace began as a square chateau expanding upon the site of the medieval citadel. The Tuileries it eventually stretched towards was then an entirely separate palace. In-between the Louvre and the Tuileries was a whole neighbourhood of buildings, streets, alleyways, and squares.

Henri IV built the grande galerie on the banks of the Seine connecting the Old Louvre to the Tuileries by 1610, but the Louvre we know today really only came together under Napoleon III in the 1850s.

Until that point, a slum was built right up to the walls of the Palace, and even within the old courtyard. Balzac, predicting that one day all this would be cleared, noted the slum with amusement as “one of those protests against common sense that Frenchmen love to make”.

The author of the Comédie humaine continues:

The retention of the block of houses which still exists along the side of the old Louvre is one of those protests against common sense which Frenchmen persist in making, apparently that Europe may feel easy as to the real measure of their intelligence, and cease to fear it. Perhaps we have some great political motive, unknown to ourselves, in this retention. It is therefore not a digression to describe this corner of the Paris of the present day; in after-years no one will be able to imagine it, and our nephews, who will doubtless see the Louvre completed, may refuse to believe that such a barbarity existed in the heart of Paris, under the windows of a palace where three dynasties received, during those thirty-six years, the elite of France and of Europe.

Everyone who comes to Paris for no more than a few days must notice between the iron gate which leads to the pont du Carrousel and the rue du Musée, a dozen houses with tumble-down walls, whose owners, considering them worthless, are unwilling to repair them, but allow them to stand as the last remnant of a former neighbourhood pulled down under Napoleon’s orders when he determined to complete the Louvre. The street and cul-de-sac, called Doyenne, are the only roadways through this dark and deserted cluster of buildings, whose inhabitants are probably phantoms, for no one is ever seen there. The roadbed, which is much lower than the chaussee of the rue du Musée, is on a level with that of the rue Froidmanteau. The houses, for this reason half-buried, are still further sunken in the perpetual shadow cast by the upper galleries of the Louvre, blackened on this side by the action of the north wind.

The gloom, the silence, the icy air, the cavernous depression of the ground, all combine to make the area of these houses a sort of crypt, in which each building is a living tomb. If we pass through this half-defunct quarter in a cab, and look up the blind alley which opens on the street, our minds shiver; we ask ourselves who can possibly live here, and whether, if we passed at night, we should see the alley swarming with cut-throats, and all the vices of Paris mantled in darkness giving themselves free rein.

This idea, alarming in itself, becomes terrifying when we notice that these strange houses are circled by a marsh on the side of the rue de Richelieu, by a paved desert towards the Tuileries, by little gardens and treacherous-looking sheds under the galleries of the Louvre, and by long stretches of broken stone left from the pulling down of former houses on the side of the old Louvre. Henry III and his minions searching for their hose, the lovers of Marguerite searching for their heads, must dance many a sarabande by the light of the moon in these deserted places, still overlooked by a chapel which remains standing as if to prove that the Catholic religion, perennial in France, survives all else.

For forty years the Louvre has cried aloud through the jaws of those broken walls, those yawning windows, “Pluck these warts from my face!” But, no doubt, some utility has been discovered in this cut-throat region — the usefulness, perhaps, of symbolizing in the heart of Paris the close alliance between squalor and splendour which characterizes the queen of capitals. And so these chill ruins (in whose bosom the newspaper of the legitimists has acquired the disease of which it is now dying), these wretched hovels of the rue du Musee, with the fence of boards inclosing them on one side, will probably have a longer and more prosperous existence than the three dynasties who have looked down upon them.

The proof that the Catholic religion, perennial in France, survives all else is apt — but the church in question, Saint-Louis-du-Louvre, was lately given over to the use of Huguenots for Protestant worship. Its demolition on the orders of Napoleon I, in order to clear room for the palace’s expansion, was compensated by the donation to the Protestants of the nearby former church of the Society of the Oratory of Jesus, a priestly society which had been suppressed during the Revolution.

The destruction of the Tuileries palace during the tumult of the Commune in 1871 meant that the huge formal courtyard — once enclosed on all sides — was now thrown open to the gardens, to the Place de la Concorde, and to the Champs Élysées beyond. In the 1980s President Mitterand put his stamp on the palace and on Paris by building the famous glass pyramid of I.M. Pei, which as a wee lad I visited shortly after it had first opened in 1989.

The Tuileries has been missed, however, and a committee was formed in 2003 to campaign for the reconstruction of the palace. Since the Finance Ministry moved out of the Louvre in the ’80s the palace has been entirely devoted to its museum. Rebuilding the Tuileries would greatly expand the musée du Louvre’s exhibition space, allowing it to put more of it’s world-class collection on display. From a design perspective, the axis of the Louvre palace does not exactly match that of the Champs Élysées, and one of the architectural tricks of the Tuileries palace’s design was to mask this slight bend in axes.

Given that Napoleon III used the palace as his primary residence, its loss means we cannot experience one of the most important locations in nineteenth-century French history, as the country reached its apogee as a world power. Luckily, the plans of the palace are preserved and many photographs would help discern the placement of all the furniture and paintings of the state apartments — saved from destruction by being packed away off-site during the Franco-Prussian War.

No decision on reconstruction has been made but funds are being raised and the debate, as ever, continues.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Amsterdam November 26, 2024

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

Andrew, may I ask where you obtained the map from which you drew the two illustrations for this post – which I am about to read? (Perhaps you mention it in the text of your post. If so, my apologies for jumping the gun!)

It’s the Turgot map of 1739. More info here.