About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Evolution of a Napoleonic Parliament

The Salle des états in the Palais du Louvre

Among the numerous rituals of the ordinary visitor’s pilgrimage to Paris — trip up the Eiffel Tower, lunch at a tourist-trap café — braving the teeming hordes in the Louvre to view da Vinci’s ‘Mona Lisa’ ranks near the top. What very few of the camera-toting hordes realise is that they are shuffling through the room that once housed France’s parliament. The history of the Palais du Louvre is long, exceptional, and varied.

Originally built as a stern castle in the 1190s, the Louvre’s secure reputation led Louis IX to house the royal treasury there from the mid-thirteenth century. Charles V enlarged it in the fifteenth century to become a royal residence, while François Ier brought the grandeur of the Renaissance to the Louvre — as well as acquiring ‘La Gioconda’. In 1793, amidst the revolutionary tumult, part of the palace was opened to the public as the Musée du Louvre, but the Louvre has always housed a variety of institutions — the Ministry of Finance didn’t move out until 1983.

Napoleon III took as his official residence the Tuileries Palace which the Louvre was slowly enlarged towards over the centuries to incorporate. The Emperor needed a parliament chamber close at hand so he could easily address joint sittings of the Senate and the Corps législatif (as the lower house was called during the Second Empire) which opened the parliamentary year. By doing so at his residence, the Bonaparte emperor was following the example left by his kingly Bourbon predecessor Louis XVIII.

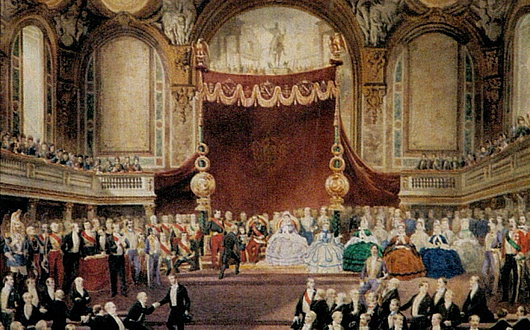

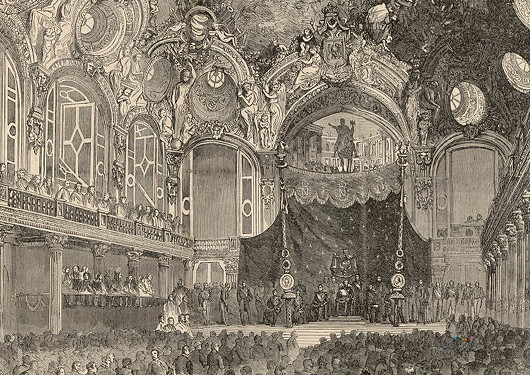

The architect Hector Lefuel incorporated the Salle des États — its name recalling the pre-revolutionary états généraux into the completion of the grand scheme completing the Louvre’s connection to the Tuileries. It was constructed between 1855 and 1857, when Napoleon III opened the legislative year in the grand hall.

Lefuel’s assistant was Richard Morris Hunt, an American who had risen through the ranks from the École des beaux-arts. So impressed was Lefuel by Hunt’s ability that it is believed the American was responsible for designing an entire section of the Louvre, the Pavillon de la Bibliothèque on the Rue de Rivoli. Hunt’s most prominent work, however, may be his much-loved façade for the Metropolitan Museum on Fifth Avenue in New York.

In 1858, Charles-Louis Muller began painting ‘Imperial France Protecting the Arts, Industry, the Sciences, and Religion’ on the ceiling, with ‘The Triumph of Napoleon I’ and ‘The Triumph of Charlemagne’ on the flanking walls. The subject matter of these paintings served to legitimate the somewhat upstart dynasty by placing it in a longer French tradition of monarchy.

With the collapse of the Second Empire after the disastrous Franco-Prussian War, the Third Republic had no state use for the Salle des états, so it was put at the disposition of the Musée du Louvre.

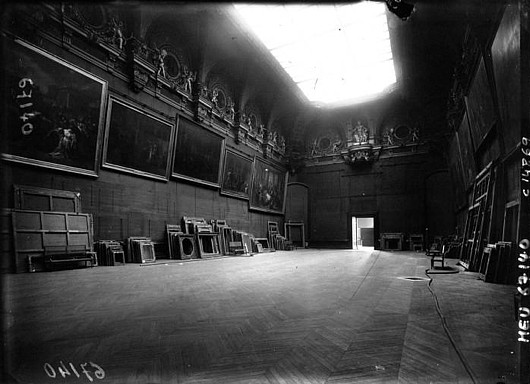

In 1886, the room was redesigned to house larger French paintings of the nineteenth century. This necessitated a complete overhaul of the Salle, and the consequent destruction of all its Napoleonic iconography and attributes. Representations of French artists were displayed in medallions arrayed around the entablature of the room.

During the First and Second World Wars, the works displayed here were mostly evacuated for safekeeping and the room used for storing frames. In between the wars, the Salle des états was home to the Delacroix retrospective of 1930.

After the war, new fashions took hold and in 1950 the room was gutted yet again. This time a restrained modern with pseudo-classical elements was employed, and Veronese’s Wedding at Cana became the star attraction of the room. In 1966, however, Veronese was upstaged by the arrival of da Vinci’s ‘Mona Lisa’ — La Gioconda — which hung on a side wall.

In 2001 the Mona Lisa was moved to the Grande Gallerie while the Salle was gutted for the third time. The Louvre engaged Peruvian architect Lorenzo Piqueras in a €4.8 million renovation incorporating new security features and moving the most popular painting to a freestanding wall so the hordes of tourists could pass around it on either side.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

- American Exuberant February 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

The decline and fall of French culture in one easy pictorial lesson!

I think it’s too bad they didn’t keep the ornate Napoleonic ceiling.

What a sad thing to see how a beautiful room has become devoid of its original beauty. I had no idea until I read this. Thank you Andrew!

Brill,brill, brill.