About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

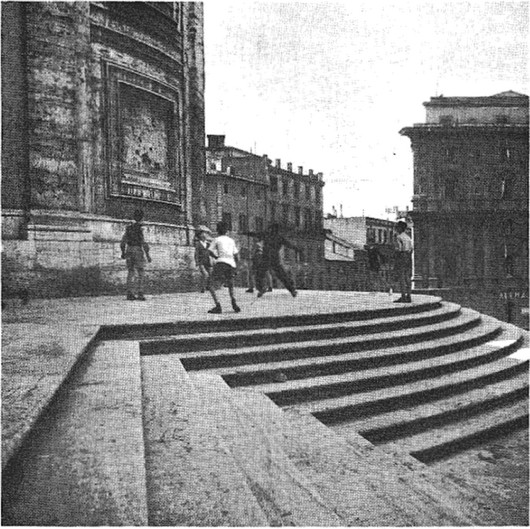

Football at S. Maria Maggiore

The enormous church of S. Maria Maggiore stands on one of Rome’s seven famous hills. Originally the site was very unkempt, as can be seen in an old fresco painting in the Vatican. Later, the slopes were smoothed and articulated with a flight of steps up to the apse of the basilica. The many tourists who are brought to the church on sight-seeing tours hardly notice the unique character of the surroundings. They simply check off one of the starred numbers in their guide-books and hasten on to the next one. But they do not experience the place in the way some boys I saw there a few years ago did. I imagine they were pupils from a nearby monastery school. They had a recess at eleven o’clock and employed the time playing a very special kind of ball game on the broad terrace at the top of the stairs. It was apparently a kind of football but they also utilised the wall in the game, as in squash — a curved wall, which they played against with great virtuousity. When the ball was out, it was most decidedly out, bouncing down all the steps and rolling several hundred feet further on with an eager boy rushing after it, in and out among motor cars and Vespas down near the great obelisk.

I do not claim that these Italian youngsters learned more about architecture than the tourists did. But quite unconsciously they experienced certain basic elements of architecture: the horizontal planes and the vertical walls above the slopes. And they learned to play on these elements. As I sat in the shade watching them, I sensed the whole three-dimensional composition as never before. At a quarter past eleven the boys dashed off, shouting and laughing. The great basilica stood once more in silent grandeur.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

That’s the back of the great basilica of course: such frenetic activity would be impossible around the other side, where the tourists enter.

It’s always something of a wasteland back there – a football game would at least bring some life to the place.

1962! The end of it all, and we all unknowing.