2013 August

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Some Norwegian Catholics

Writers, politicians, journalists, academics — Norway’s Catholics seem an intellectual bunch. The Church in Scandinavia is on a slow but steady ascendant, and it’s telling (of both the rise and fall of many) that there are now more seminarians studying for the priesthood for the Nordic countries than there are for all of Ireland.

As a Norwegian acquaintance of ours was ordained for the Diocese of Oslo within the past year, I thought a little jaunt through a handful or two of Norwegian Catholics might be interesting. There are some I would have liked to included — the conversion of the former Lutheran ecumenist Ola Tjørhom provoked controversy and Wilhelm Wedel-Jarlsberg preceded Christopher de Paus as a papal chamberlain — but there is only so much time and space and effort.

Of those mentioned here below, only Sigrid Undset has achieved worldwide fame. Her work Kristin Lavransdatter is an absolute must for any serious reader of literature and was recently re-translated into English by Penguin. (more…)

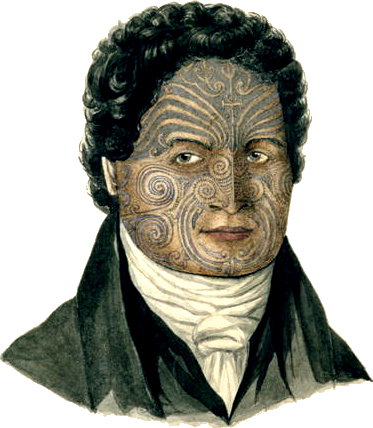

A Maori in Buenos Aires

The Argentine stopover of Te Pēhi Kupe

So  far as I can tell, the first Maori to visit Argentina (or the United Provinces of the River Plate as it was then called) was the young nobleman Te Pehi Kupe in October 1824. (The name is spelt varyingly as Te Pēhi Kupe, Tupai Cupa, Te Pai Kupa, and Tippahée Cupa). Te Pehi was born on the North Island, probably around 1795, and was a senior-line descendant of Toarangatira (founder of the Ngati Toa tribe) as well as an uncle to the more famous Ngati Toa chief, Te Rauparaha.

far as I can tell, the first Maori to visit Argentina (or the United Provinces of the River Plate as it was then called) was the young nobleman Te Pehi Kupe in October 1824. (The name is spelt varyingly as Te Pēhi Kupe, Tupai Cupa, Te Pai Kupa, and Tippahée Cupa). Te Pehi was born on the North Island, probably around 1795, and was a senior-line descendant of Toarangatira (founder of the Ngati Toa tribe) as well as an uncle to the more famous Ngati Toa chief, Te Rauparaha.

Most of New Zealand was a bit of a mess at the time, as various Maori tribes fought each other for land to grow potatoes on. Te Pehi Kupe, being a chief and military leader, was desirous to go to Europe in order to obtain weapons for his tribe. When the British ship Urania went past the southern tip of the North Island, Te Pehi forced himself aboard despite the violent resistance of the ship’s officers and crew. When asked what he desired by the Urania‘s captain, Richard Reynolds, Te Pehi replied in broken English, “Go Europe, see King George”.

Captain Reynolds did not think this a good idea and, knowing the Maori to be good swimmers, tried to have him thrown overboard, but the native nobleman’s physical strength prevented this. (And a good thing, too, as Te Pehi managed to save the Captain from drowning later on in the journey.)

The Urania made its return to England with Te Pehi Kupe aboard, calling at Lima and then sailing around the Southern Cone, where they called in at Buenos Aires. George Thomas Love provides us with an account of the Maori’s arrival in A Five Years’ Residence in Buenos Ayres (published in 1827):

In the month of October, 1824, the visit of a New-Zealand chief to Buenos Ayres, by name Tippahée Cupa, attracted much curiosity; he arrived in the British ship Urania, Captain Reynolds. Tippahée came alongside this ship in Cook’s Straits, with a war canoe filled with his people, and, in spite of the remonstrances and even force used by Captain R. refused to quit the vessel, expressing his determination to proceed to England. He bade his followers an affectionate adieu, enjoining obedience to his successor during his absence. The Urania sailed for London with her passenger the 8th December, 1824.

Tippahée, when he first arrived in Buenos Ayres, was clothed in an old red coat, formerly belonging to a London postman. The English paid him many attentions, inviting him to dine at their houses, and new clothing him. His behaviour at table was easy and unembarrassed; and, when requested, he would perform the dances and war songs of New Zealand. He understood a little of the English language, and spoke a few words of it; his intelligent manners, and circumspect conduct, rendered him an universal favourite.

On the map he could trace the ship’s course from New Zealand to Lima and Buenos Ayres. He knew an Englishman immediately; the Spaniards he did not much admire, fancying they viewed him with contempt, and was glad to get among Englishmen. His age is about forty; he possesses amazing strength; his tattooed face and appearance always attracted a crowd after him in Buenos Ayres.

On board ship he was found very useful, doing all sorts of work, but he positively declined to go aloft. The fate of Captain Thompson, and the crew of the British ship Boyd, ought to bespeak caution in using coercion with these savage chieftains of New Zealand.

In Cruise’s book of New Zealand, Tippahee was shewn a picture of a chief of his country, with which he was greatly delighted. The object of his journey to England is to solicit arms and ammunition, to place him upon a par with a rival chief, who possesses those requisites.

In England, Te Pehi was indeed presented to King George IV. He also learned to ride, visited factories, was given many gifts, and survived the measles before leaving England aboard the Thames on 6 October 1825. In Te Pehi’s absence abroad, peace had been agreed between the Ngati Toa and their Ngati Apa rivals. Ngati Toa eyes soon turned to the South Island, and during the military campaign there Te Pehi Kupe was killed, his body cooked and eaten, and his bones turned into fish hooks.

Still, at least he enjoyed Buenos Aires before he died.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories