About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Palacio Legislativo Federal

MOST OF THE major American countries have large parliamentary buildings built at the height of their prosperity in the decade before and after 1900, but Mexico is a particular exception. (Brazil, for complicated reasons, is another). In the 1890s, the government of President Porfirio Díaz decided that it needed a grand legislative palace whose magnificence would be worthy of the head of state’s own grand appearance. A competition was held and an entry chosen as the winner, but the victor was disregarded in favour of a new design by a French architect.

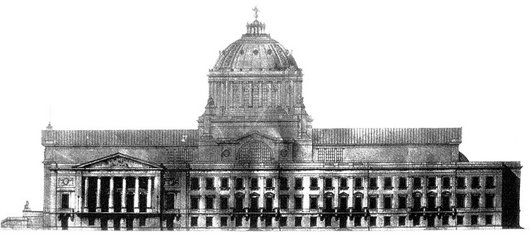

Émile Bénard had assisted the great Charles Garnier in draught work for the celebrated Paris Opera House which now bears that architect’s name. In the 1890s, Bénard became famous for winning Phoebe Hearst’s architectural competition for the campus of the University of California at Berkeley with his entry “Roma”. The Spectator wrote from the London of the day, “On the face of it this is a grand scheme, reminding one of those famous competitions in Italy in which Brunelleschi and Michelangelo took part. The conception does honor to the nascent citizenship of the Pacific states.” Unfortunately, very little of Bénard’s scheme for the academic complex was completed.

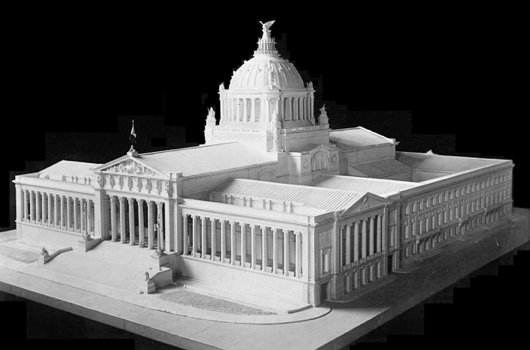

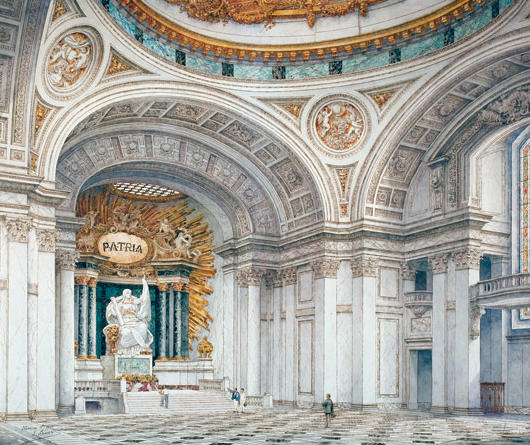

Bénard planned a large palace, the Palacio Legislativo Federal, to house the Congress of the United Mexican States. It was fronted by a massive colonnade providing shade from the sun and incorporated grand plenary chambers for the two houses of the Mexican congress: the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies. The centrepiece was a large gilded dome over a rotunda with a larger-than-life-scale statue of “Patria” — the personification of the Mexican fatherland.

Work began in 1902 but was not completed in time for the centenary of independence in 1910. By that time, Díaz’s regime had larger concerns to worry about. The ‘Mexican Revolution’ broke out in the same centenary year when a wealthy and envious rival of the iron-fisted president sparked a revolt after being imprisoned for challenging Díaz in an open presidential election. The decade-long insurrection eventually overturned the old authoritarian liberal republican regime and layed the foundations for the revolutionary anti-clerical regime that ruled Mexico for most of the twentieth century. But work on the Palacio stopped and the empty steel frame of the dome and front of the building sat unfinished in the Plaza de la República, an embarrassment to the new rulers.

Finally, in the late 1930s, the government commissioned architect Carlos Obregón Santacilia to preserve the stillborn dome and transform it into a Monument to the Revolution. This was done in a restrained eclectic art deco form that included allusions to the pre-Columbian artistic tradition of the country.

But what about the Congress? The Senate continued to meet in its old seat until 2011, while the Chamber of Deputies met in a smaller beaux-arts structure curiously started around the time construction on the Palacio Legislativo Federal stopped. In 1977, Mexico’s one-party PRI regime began a political transition to multi-party rule which included the expansion of the lower house from 186 deputies to 400 deputies. As the public purses were flush with cash from a commodities boom, it was decided to demolish a vast old railway terminal and yard and built a modern new legislative palace on the site. The building is impressive, but not particularly beautiful.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Christ Church December 29, 2024

- A Christmas Gift from the Governor December 24, 2024

- Oude Kerk, Amsterdam December 24, 2024

- Gellner’s Prague December 19, 2024

- Monsieur Bayrou December 18, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

The newest legislative building looks like some huge, modern prison with that front face-on view in the photo. Absent the dull circular Mexican federal seal, there’s not a curve anywhere in the massing of the structure, even down to the linear, monochrome flower beds.It’s like something out of a recent sci-fi movie.

If only it was built! This story reminds me of what happened in Cape Town.In 1874 plans were in progress for the construction of a new Parliament building in Cape Town (The Cape Colony was by then a self-governing so-called “dominion” of the British Empire of the time).A competition was announced inviting designs for a structure that would not exceed 50000 pounds.The competition was won by Charles Freeman – probably the most talented architect of the time in Cape Town.His handsome design was for a building with four corner pavilions ,a columned entrance portico – all crowned with a gracious dome. In addition sculptures were to be erected on the parapets and fountains would beautify the frontage of the building. A beautiful watercolour of the planned design survives.

As soon as building commenced problems were encountered when it was found that the foundations would have to be dug much deeper than the plans called for,probably doubling the original cost estimated by Freeman. A nasty legal case ensued with Freeman unjustly being accused of withholding information about total costs.Strangely, his plans were also criticised for being a copy of a building in America – but I have not discovered which building was being referred to.It was also claimed that the foundations were faulty and badly designed. Freeman was then fired and the Public Works Department under Harry Greaves then submitted a new design which somewhat followed Freeman’s masterful plan. The result was a humdrum Victorian structure completely lacking the elegance of Freeman’s original design. The new Parliament building lacked the handsome dome; and the elegant sculptures and fountains were also absent.The building was finally completed in 1884 and eventually cost a whopping 220,000 pounds. Freeman went on with his profession in Cape Town and designed such iconic city buildings as the main branch of the Standard Bank of South Africa in Adderley street and the Metropolitan Methodist Church on Greenmarket Square,amongst many other buildings. Such was the confusion with the Parliament building project at the time that even the original cornerstone has gone missing!