About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The Historical Sale at Adam’s

800 Years: Irish Political, Literary, and Military History – 18 April 2012

THE ANCIENT PRACTICE of lèche-vitrine is one hallowed by time and tradition. I remember one December day I had a lunch appointment with a friend who worked at the late, lamented Anglo-Irish Bank on Stephen’s Green in Dublin and, being early, I nipped a few doors down to the auction house Adam’s to engage in a bit of what I like to call thing-avarice (which the Germans probably have a word for). We do enjoy taking the occasional peek round the Dublin auction houses to see what’s what, and to examine the cabinet of curiosities that come out from ancient houses and rotting flats and appear in these bright places where commerce and refinement play their strange little waltz. When it comes down to it, though, it’s really just about having nice things — the sort of stuff you want lying around the house inexplicably.

Anyhow, the historical auction at Adam’s is coming up on 18 April and sure enough their senior rival Whyte’s is having a similar sale just a few days later on 21 April. We’ll only look at Adam’s here — if we considered Whyte’s as well, we’d be here all day.

One of the most interest lots up for auction is a set of twenty-five documents relating to the Wyse family of Waterford and the Priory, later the Manor, of St. John. The Wyse family were part of the Flemish plantation in Wales established by England’s Henry I after 1100, and descendants of that Pembrokeshire family made their way to Waterford where they enjoyed a certain prominence.

Through the marriage of Thomas Wyse to the Princess Letitia Bonaparte, niece of Napoleon I, the name of the Irish family became Bonaparte-Wyse. Andrew Bonaparte-Wyse (1870-1940) was an Irish educationalist, civil servant, and hardline unionist who, after partition, was the only Catholic Permanent Secretary in the Northern Irish Civil Service. (It took until 1969 for the next Catholic to reach that rank). Andrew B-W was a Knight of Malta, Commander of the Order of the Bath, Commander of the Order of the British Empire, a Member of the Royal Irish Academy, married a Russian countess, and had a son who served in the Free French Navy during the Second World War. Bang! But anyhow, he’s nothing to do with anything.

Through the marriage of Thomas Wyse to the Princess Letitia Bonaparte, niece of Napoleon I, the name of the Irish family became Bonaparte-Wyse. Andrew Bonaparte-Wyse (1870-1940) was an Irish educationalist, civil servant, and hardline unionist who, after partition, was the only Catholic Permanent Secretary in the Northern Irish Civil Service. (It took until 1969 for the next Catholic to reach that rank). Andrew B-W was a Knight of Malta, Commander of the Order of the Bath, Commander of the Order of the British Empire, a Member of the Royal Irish Academy, married a Russian countess, and had a son who served in the Free French Navy during the Second World War. Bang! But anyhow, he’s nothing to do with anything.

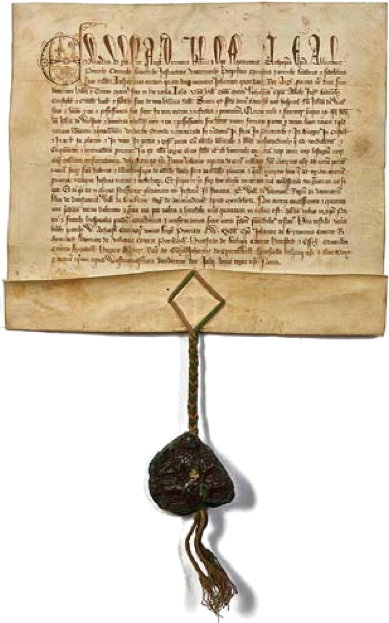

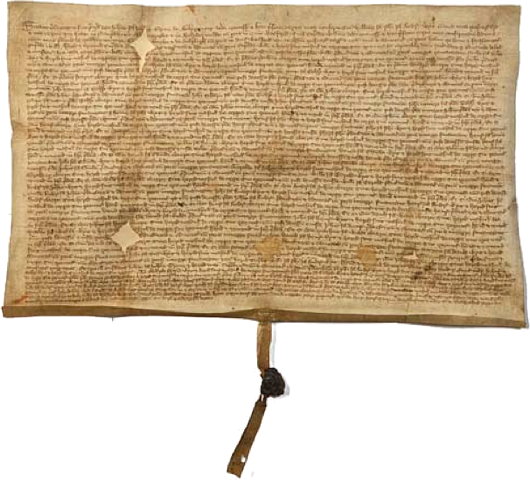

Among the Wyse lot is (left) the 12 July 1315 inspeximus of King Edward II (who met with an unhappy end) confirming the rights and privileges of the hospital run by the Knights of St John (now more often called the Order of Malta) in Waterford. Below is a 1375 deed granting lands in Co. Waterford to William fitz Philip fitz Andrew Wys and his legitimate heirs and descendants. The entirety of the lot, with an estimate of €100,000-€150,000, might be of particular interest to sigillographers.

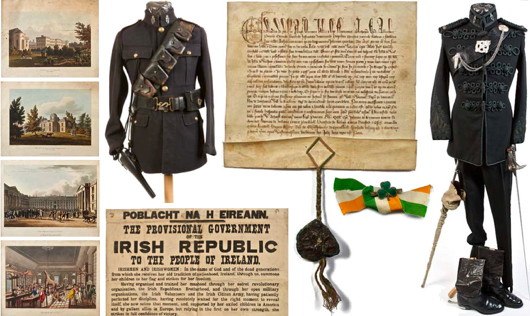

Here’s something that’d appeal to PH, being the aficionado of all things Trinity: original coloured engravings of four different college scenes drawn and etched by W.B. Taylor, aquatinted by R. Havell & Son. They depict (clockwise from top left): “Museum of T.C.D.”, “The Grand Square, T.C.D.”, “S.W. View of the Library”, and “N.E. View of the College Observatory”. Printed in 1819/20, various sizes, framed, €800-€1200.

A portrait of Daniel O’Connell, nothing to write home about and he’s been depicted much better elsewhere. This portrait’s too dark for my liking — I prefer a bit of light and colour myself. Oil on canvas, 30 in. x 24 in., €8,000-€12,000.

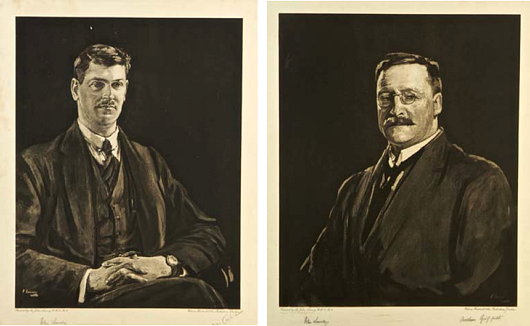

Now these are much more to my liking. Portrait prints of Collins and Griffith by Sir John Lavery RA RHA from 1922, each signed in pencil by the artist and (!) the sitter. They’d look perfect behind one’s desk looking over each shoulder. The portraits were done by Lavery amidst the Treaty negotiations, during which he and his wife did their most to help the Irish party. Framed 17 in. x 13 in., €4,000-€6,000.

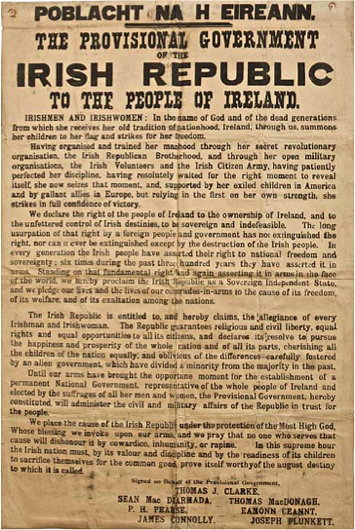

This, though, is the business: an original printing of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic from Easter Monday 1916. Considering its printing on cheap paper, this copy is in excellent condition. Of the over 2,000 printed, only around 50 are known to still be in existence — this one preserved by a Co. Longford family with Republican affiliations. 30 in. x 20 in., €60,000-€80,000.

If you fancy dressing up and playing B-Specials (and we imagine the Sybarite probably does), then we have above an Ulster Special Constabulary high-neck platoon sergeant’s uniform from the 1940s. Crowned harp on the neck, rank stripes on the right arm, marksman’s crossed-rifle badge on left arm cuff, and 1908 webbing, belt, pouches, and cross-strap. Would suit mad Ulsterman or fan thereof. €2,000-€2,500. At right, an Royal Irish Constabulary District Inspector’s First-Class Uniform, this one having belong to a chap named George Hugh Mercer, Private Secretary to the Inspector-General of the RIC in 1911. Crafted by T.G. Phillips of 4 Dame Street, Dublin, it consists of dress jacket, trousers, leather cross belt & back pouch, sword belt, sword and leather knot, and leather boots (not contemporary), as well as a service history with information on D.I. Mercer and his wife.

If you fancy dressing up and playing B-Specials (and we imagine the Sybarite probably does), then we have above an Ulster Special Constabulary high-neck platoon sergeant’s uniform from the 1940s. Crowned harp on the neck, rank stripes on the right arm, marksman’s crossed-rifle badge on left arm cuff, and 1908 webbing, belt, pouches, and cross-strap. Would suit mad Ulsterman or fan thereof. €2,000-€2,500. At right, an Royal Irish Constabulary District Inspector’s First-Class Uniform, this one having belong to a chap named George Hugh Mercer, Private Secretary to the Inspector-General of the RIC in 1911. Crafted by T.G. Phillips of 4 Dame Street, Dublin, it consists of dress jacket, trousers, leather cross belt & back pouch, sword belt, sword and leather knot, and leather boots (not contemporary), as well as a service history with information on D.I. Mercer and his wife.

Here’s a lovely artefact: the tricoloured ribbon badge worn by Geraldine Plunkett Dillon following the execution of her brother, Joseph Mary Plunkett (for his leading role in the Easter Rebellion) and the imprisonment of her parents, Count & Countess Plunkett, as well as her brothers Jack and George.

Mrs Dillon wrote in her memoir:

I got some South African medal ribbon because it was green, white, and orange and made it into a bow which I wore everywhere. A big policeman in Dame Street stopped me and said the tricolour would get me into trouble. I said, ‘I have one brother shot and two brothers sentenced to death and my father and mother in jail’. He said ‘You’re Plunkett, you can wear it’. He was seven foot tall.

As the auction catalogue notes of the colours of the South African Medal ribbon, “the green stripe represent[ed] the South African veldt, the orange the peoples of the two Boer republics, and the central white stripe the vastness of the landscape over which the war was fought, and the bond that had been broken.”

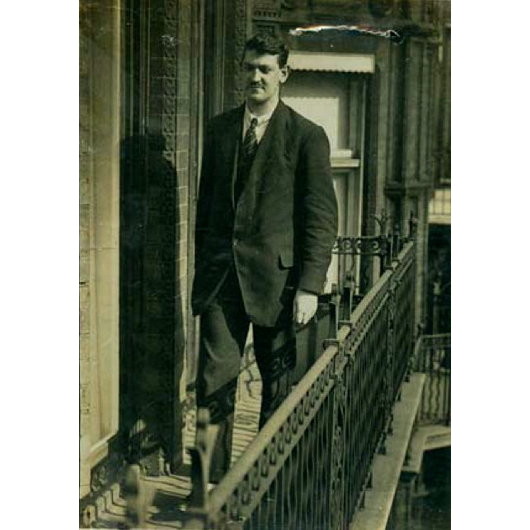

This mounted photograph of Michael Collins was taken in 1921 during the Anglo-Irish treaty negotiations. Approximately 8 in. x 6 in., €1,500-€2,500.

The catalogue notes cautiously “said to be at No. 10 Downing Street”, but it is very clearly the balcony of No. 22, Hans Place, the Knightsbridge headquarters of the Irish negotiating team. This particular balcony is on the rear of No. 22 and faces on to Pont Street — I’ve walked past it many times. During the negotiations, Collins heard Mass every morning at the Brompton Oratory nearby before proceeding to Downing Street for the actual talks.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

- Waarburg October 2, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

Marvellous, beautiful post.

“As the auction catalogue notes of the colours of the South African Medal ribbon, “the green stripe represent[ed] the South African veldt, the orange the peoples of the two Boer republics, and the central white stripe the vastness of the landscape over which the war was fought, and the bond that had been broken.”

Curious that the white stripe should represent a broken bond. In the case of the Irish tricolour I though the white represented the desire for peace between an orange Ulster and a naturally green Ireland. Versatile shade, that white.

Andrew, Just catching up with this post…having been pulled in other directions. Good work. Nice to learn of the Michael Collins connection to the Brompton Oratory.