About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

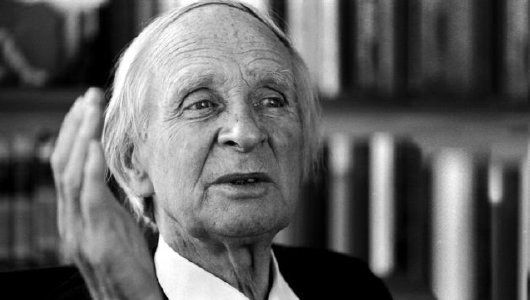

Cooking with Sir Laurens van der Post

East and West Meet at the Cape

The Cape Malays came up with dishes that are all so a part of the South African way of life that they have become almost sacramental substances. Among them are bobotie, sosaties, and bredie. Bobotie, a kind of minced pie, is to South African what moussaka is to the Greeks. Sosaties, or skewered and grilled meats are what shashlyk are to the people of the Caucasus and shish kabob to the Turks. The stew called bredie is what goulash is to Hungarians.

A basic bobotie begins with minced lamb or beef, a little soaked bread, eggs, butter, finely chopped onion, garlic, curry powder and turmeric. All are mixed together, put in a pie dish with meat drippings, and baked in a low oven for a time. The moment the mixture begins to brown, the dish is taken from the oven and some eggs beaten up with milk are poured over the top; then the dish is put back into the oven and baked very slowly to a deep brown. The pace of the cooking is important: if the oven is too hot the bobotie will be dry, and that should never happen, for an ideal bobotie is eaten moist, over rice.

What I have described is (I believe) bobotie as it was eaten in the beginning, but it is no linger the bobotie eaten in South Africa, except in Malay homes. In my own home, for instance, we added a handful of finely chopped blanched almonds and some raisins to the mixture. The simple egg-and-milk mixture poured over the bobotie halfway through the baking (a mixture that can easily turn into a stodgy baked custard) was scorned by our cooks. At a late stage in the cooking they would bat bread crumbs fried in drippings into the mixture and bake it quickly in a hot oven. In her famous book Where Is It? Hildagonda Duckitt, the Fannie Farmer of South Africa, says that a teaspoon of sugar should be added to the meat mixture, and an ounce of tamarind water gives the dish an exceptionally pleasant, tart flavor. But these are only a few variations, and there are almost as many as there are homes in South Africa.

The word sosatie is derived from two Malay words: saté, which means “spiced sauce”; and sésate, which means “meat on a skewer.” This second great standby of the South African diet is usually made of mutton cut into small cubes suitable for spiking on thin wooden skewers. Originally the Cape Malays marinated the meat in a mixture of shredded fried onions, curry powder, chilies, garlic and a generous quantity of tamarind water. They usually did this early in the afternoon and left the meat in the marinade until the next day. They would then skewer the cubes of meat with alternate pieces of mutton fat, and roast them on an open fire or fry them in a heavy skillet. Just before the sosaties were ready the cook would boil the marinade in a saucepan until its ingredient were cooked and the liquid reduced, and he would serve the sosaties with rice and this sauce. But I have had Malay sosaties in which the green ginger also went into the marinade and during the simmering stage the cook added a few bay leaves, an orange leaf or two and another spoonful of curry. Again, the variations are endless; the Olympian Miss Duckitt rounds out her marinade with either vinegar or the juice of lemons (we always used lemon juice at home), sugar and milk. Because of the Muslim proscription against pig products, the Malays never skewered bacon with their sosaties, but it is quite common among other Cape residents nowadays to do sosaties with alternate cubes of mutton and squares of bacon, all conventionally marinated.

The last of the three great Cape Malay main dishes is the stew called bredie. Almost every country in the Western world has its meat stew. The Irish, of course, have Irish stew; the English, Lancashire hotpot; the Dutch, hutspot; the Germans, Eintopf; and the Hungarians, goulash. But only in South Africa is the dish of Oriental origin. The very word bredie is significant: it is a Malagasy word from Madagascar, and between the east coast of Madagascar and the world of India and Malaya there has been a steady coming and going since recorded history began. To this day, the bredies are a culinary reminder of that traffic.

A Cape Malay cook starts a bredie by browning thinly sliced onions in mutton fat, butter or oil, in that order of preference. Meat or fish is then laid over the onions and gently braised. The chosen vegetables, sliced or cubed, are placed on top of the meat with various seasonings, but always with chiles. Curiously, the vegetable used n one of the earliest forms of bredie was pumpkin, even though the Dutch regarded it as food fit only for slaves. Today, pumpkin bredie is one of South Africa’s almost mystical dishes, and if the pumpkin is firm and crisp it can be excellent. Some Cape Malay cooks add a little salt, a few chiles and a potato or two to the pumpkin; others flavor it with green ginger, cinnamon sticks, a few cloves and a little chopped garlic. The variations are endless, and pumpkin bredies are only a subdivision of them. I have had wonderful cauliflower bredies, and others made with green beans, curried beans, turnips, kohlrabi, celery, carrots, peas, button turnips, and a spinach bredie enlivened by the addition of sorrel.

The variation that most stimulates the South African palate, however, is unquestionably tomato bredie. I know about a dozen recipes for cooking tomato bredie, and all of them are good; the one in Miss Duckitt’s Where Is It? is probably as good as any. All bredies begin roughly in the way I have described, but in this recipe boneless mutton is cut into small pieces and browned with onions over a fairly hot fire. Large tomatoes are cut into slices or passed through a mincing machine; if the tomatoes are not quite ripe, sugar and slat as well as the traditional chiles are added. The braised meat, crisp fat and tomato are then stewed as slowly as possible until the liquid in the pot is reduced to a rich, thick gravy. Upcountry, we often added some peeled, cored and sliced quinces to the mixture, cutting the razor edge of the quince flavor with a small addition of sugar. To my mind there is no stew, goulash or hotpot to equal bredie cooked this way and eaten with simple but perfect rice.

Bobotie

Baked Ground Lamb Curry with Custard Topping

1 slice homemade-type white bread, 1 inch thick, broken into small bite

1 cup milk

2 tablespoons butter

2 pounds coarsely ground lean lamb

1½ cups finely chopped onions

2 tablespoons curry powder, preferably Madras type

1 tablespoon light-brown sugar

1 teaspoon salt

½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

¼ cup strained fresh lemon juice

3 eggs

1 medium-sized tart cooking apple, peeled, cored and finely grated

½ cup seedless raisins

¼ cup blanched almonds, coarsely chopped

4 small fresh lemon or orange leaves, or substitute 4 small bay leaves

Preheat the oven to 300 degrees (F). Combine the bread and milk in a small bowl and let the bread soak for at least 10 minutes.

Meanwhile, in a heavy 10- to 12-inch skillet, melt the butter over moderate heat. When the foam begins to subside, add the lamb and cook it, stirring constantly and mashing any lumps with the back of a spoon, until the meat separates into granules and no traces of pink remain. With a slotted spoon, transfer the lamb into a deep bowl.

Pour off and discard all but about 2 tablespoons of fat from the skillet and drop in the onions. Stirring frequently, cook for about 5 minutes, until the onions are soft and translucent but not brown. Watch carefully for any sign of burning and regulate heat accordingly. Add the curry powder, sugar, salt and pepper, and stir for 1 or 2 minutes. Then stir in the lemon juice and bring to a boil over high heat. Pour the entire mixture into the bowl of lamb.

Drain the bread in a sieve over a bowl and squeeze the bread completely dry. Reserve the drained milk. Add the bread, 1 of the eggs, the apple, raisins, and almonds to the lamb. Knead vigorously with both hands or beat with a wooden spoon until the ingredients are well combined. Taste for seasoning and add more salt if desired. Pack the lamb mixture loosely into a 3-quart soufflé dish or other deep 3-quart baking dish, smoothing the top with a spatula. Tuck the lemon, orange or bay leaves beneath the surface of the meat.

With a wire whisk or rotary beater, beat the remaining 2 eggs with the reserved milk for about 1 minute, or until they froth. Slowly pour the mixture evenly over the meat and bake in the middle of the oven for 30 minutes, or until the custard is a light golden brown.

Serve at once, directly from the baking dish. Bobotie is traditionally accompanied by hot boiled rice.

Sosaties

Skewered Marinated Lamb with Curry-Tamarind Sauce

3 tablespoons rendered bacon fat or lard

1½ cups finely chopped onions

1 tablespoon curry powder, preferably Madras type

1 teaspoon ground coriander

½ teaspoon ground turmeric

1 cup tamarind water or substitute ½ cup strained fresh lemon juice combined with ½ cup water

1 tablespoon apricot jam

1 tablespoon light-brown sugar

2 pounds lean boneless lamb, preferably leg, trimmed of excess fat and cut into 1½ inch cubes

1 teaspoon salt

Freshly ground black pepper

4 fresh lemon leaves or 4 medium-sized bay leaves

2 teaspoons finely chopped garlic

2 teaspoons finely chopped fresh hot chiles

2 medium-sized onions, peeled, cut lengthwise into quarters and separated into individual layers

¼ pound fresh pork fat, sliced ¼ inch thick and cut into 1-inch squares

1 tablespoon flour

2 tablespoons cold water

Starting a day ahead, heat the bacon fat or lard in a heavy 8- to 10-inch skillet over moderate heat until it is very hot but not smoking. Drop in the chopped onions and, stirring frequently, cook for about 5 minutes, or until they are soft and translucent but not brown. Watch carefully for any sign of burning and regulate the heat accordingly. Add the curry powder, coriander and turmeric, and stir for 2 or 4 minutes longer, Then add the tamarind water (or lemon-juice mixture), jam and sugar, and continue to stir until the mixture comes to a boil. Reduce the heat to low and simmer partially covered for 15 minutes. Pour the curry-and-tamarind mixture into a large, shallow bowl and cool to room temperature.

Sprinkle the lamb with the salt and a few grindings of pepper. Toss the lamb, lemon or bay leaves, garlic and chiles together with the cooled curry mixture, cover tightly with foil or plastic wrap, and marinate the lamb in the refrigerator for at least 12 hours, turning the cubes over from time to time.

Light a layer of coals in a charcoal broiler and let them burn until a white ash appears on the surface, or preheat the broiler in your oven to its highest point.

Remove the lamb from the marinade and string the cubes tightly on 6 long skewers, alternating the meat with the layers of onions and the squares of fresh pork fat. Broil 4 inches from the heat, turning the skewers occasionally, until the lamb is done to your taste. For pink lamb, allow about 8 minutes. For well-done lamb, which is more typical of South African cooking, allow 12 to 15 minutes.

Meanwhile, prepare the sauce. Discard the lemon or bay leaves and pour the marinade into a small saucepan. Bring to a boil over high heat, then reduce the heat to low. Make a smooth paste of the flour and 2 tablespoons of cold water and, with a wire whisk or spoon, stir it gradually into the simmering marinade. Cook, stirring frequently, until the sauce slightly thickens. Taste for seasoning.

To serve, slide the lamb, onions, and fat off the skewers onto heated individual plates. Present the sauce separately in a small bowl or sauceboat.

Tamarind Water

(Well, Tamarind Water)

2 ounces dried tamarind pulp

1½ cups boiling water

Place the tamarind pulp in a small bowl and pour the boiling water over it. Stirring and mashing it occasionally with a spoon or your hands, let the tamarind soak for about 1 hour, or until the pulp separates and begins to dissolve in the water. Rub the tamarind through a fine sieve set over a bowl, pressing down hard with the back of a spoon before discarding the seeds and fibers. Cover tightly and refrigerate until ready to use. Tamarind water can be kept safely for a week or so.

Tomato Bredie

Lamb-and-Tomato Stew

Bredie: “Bredie” is an old Cape name for a thick, richly flavored meat-and-vegetable stew. Both the name and the stew are of Malay origin, but “bredies” are now popular now throughout South Africa. They are almost always made with lamb or mutton — preferably the fattier cuts of these meats, because of their richer flavor. While onions and chiles dominate the seasonings, a typical “bredie” is also cooked with — and named for — a vegetable such as tomato, pumpkin, green beans, cabbage, dried beans, or cauliflower.

2 tablespoons vegetable oil

1½ pounds boneless shoulder, cut into 1-by-2-inch chunks

1 large onion, peeled and cut crosswise into slices 1/8 inch thick

1 teaspoon finely chopped garlic

6 medium-sized firm ripe tomatoes (about 2 pounds), peeled and cut crosswise into slices ¼ inch thick

1 tablespoon finely chopped fresh hot chiles

2 whole cloves

1 teaspoon sugar

1 teaspoon salt

In a heavy 10- to 12-inch skillet, heat the oil over moderate heat until a light haze forms over it. Add the lamb and brown it a few pieces at a time. Turn the pieces frequently with a slotted spoon and regulate the heat so that they color richly and evenly without burning. As the lamb browns, transfer the pieces to a plate.

Pour off and discard all but about 2 tablespoons of fat from the skillet and drop in the onion slices and the garlic. Stirring frequently and scraping any brown particles that cling to the bottom of the pan, cook for 8 to 10 minutes, or until the onions are soft and golden brown. Stir in the tomatoes, chiles, cloves, sugar and salt, then add the lamb and any juices that have accumulated around it. Reduce the heat to the lowest possible point, cover tightly, and cook the bredie for 1 hour, stirring it from time to time.

Remove the cover and, stirring and mashing the tomatoes occasionally, simmer for 30 to 40 minutes longer, or until the lamb is very tender and most of the liquid in the pan has cooked away. The sauce should be thick enough to hold its shape almost solidly in the spoon.

Taste for seasoning. Pick out and discard the cloves and serve the bredie at once from a heated platter, accompanied by hot boiled rice.

Klappertert

Coconut Pie

1½ cups sugar

1½ cups water

3 cups finely grated fresh coconut

6 tablespoons unsalted butter, cut in small bits

2 eggs plus 1 egg yolk, lightly beaten

1/8 teaspoon vanilla extract

2 tablespoons apricot jam

1 baked 9-inch short-crust pastry pie shell

8 strips candied citron, 1inch long by 1/8 inch wide

Combine the sugar and water in a small saucepan and bring to a boil over high heat, stirring until the sugar dissolves. Cook briskly, undisturbed, until the syrup reaches a temperature of 230 degrees F on a candy thermometer or until a few drops spooned into ice water immediately form coarse threads.

Remove the pan from the heat, add the coconut and butter, and stir until the butter is completely melted. Let the coconut mixture cool to room temperature, then vigorously beat in the eggs and vanilla, continuing to beat until the eggs are completely absorbed.

Meanwhile, preheat the oven to 350 degrees F. In a small pan, melt the apricot jam over low heat, stirring constantly. Then rub the jam through a fine sieve with the back of a spoon, and brush the jam evenly over the bottom of the baked pie shell.

Pour the coconut mixture into the pie shell, spreading it and smoothinf the top with a spatula. Bake in the upper third of the oven for about 40 minutes, or until the filling is firm to the touch and golden brown. Arrange striops of citron in a sunburst pattern in the center of the pie. Serve the klappertert warm or at room temperature; accompanied if you like by whipped cream.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

Andrew …

You know whenever I am to bring something edible to an event in the country I now live in (like the wedding in Zuid-Holland that I have just been invited to this month), I always like to dazzle the locals with our wonderful Boerekos. My Bobotie recipe handed down from Cape origins is always is a smashing hit. I like my Bobotie over all others I have had, if I may be so smug. But I was amused the other day when I noticed there is now a Bobotie “instant mix” at Albert Heijn … I think it was by Knorr. I kid you not! But the dish though that causes the most swooning is without question — Melktert. When my mom made us these delights, she would make one for us kids to eat immediately (so as to keep us from hoovering up the main one) and after making the filling she would allow us to polish off the remnants in the bowl and on the appurtenances. Tannies would use a doily on top of the tart and grate cinnamon over it, lifting off the doily afterwards and leaving a pretty pattern on top of the tart. Nothing as lekker as a homemade Melktert! Another favourite for me is Souskluitjies … check out Cooksister.com if you’re curious.

Groete …

Like Doulgas MacArthur said so famously, I shall return. Or like what was stamped into the soap in my suite at the -oh what was the name of that hotel – the one in Montreal – we went there as mere small things to try and reknit together my parents marriage – lived like kings – the one on the hill =Frontenac – that’s it- the Hotel Frontenac – well 15,000 grand later in 1967 we left with souvenir soaps that said Je Reviens and the name of a good divorce lawyer. We never did Je Reviens But I shall this time.