About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Old Master Paintings at Sotheby’s

A Florentine Artist, The Madonna & Child Enthroned Flanked by Saints Bridget & Michael

1450; Tempera on panel, 72 in. x 85 in.

QUITE A FEW interesting pieces up for auction today as part of Old Master Week at Sotheby’s in New York. The above altarpiece has been attributed to various artists. For much of its life was called the Poggibonsi Triptych, but scholars now believe it to be the work of the Master of Pratovecchio. This attribution was supported by no less an authority than Roberto Longhi, who (as the catalogue notes point out) “considered him an artist of note who contributed to the Florentine transition from the early fifteenth-century serenity and intimacy of Fra Angelico and Filippo Lippi to the more dynamic forms found later in the century.”

The altarpiece, commissioned from a certain Giovanni di Francesco in 1439, was acquired by the J. Paul Getty Museum in California, which is now auctioning to raise funds for future acquisitions.

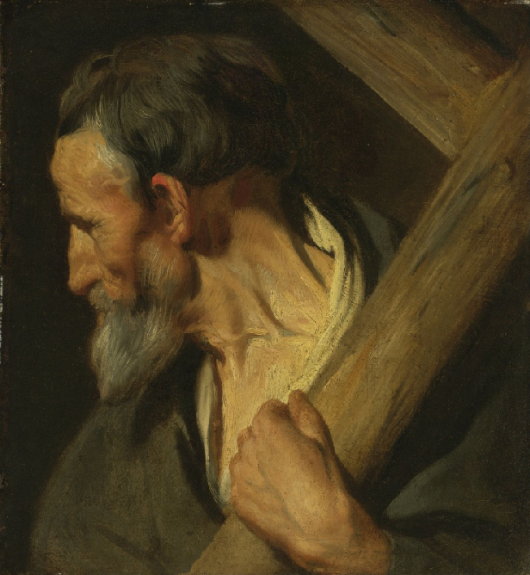

Jacob Jordaens, Saint Andrew

c. 1620; Oil on canvas, 21½ in. x 19½ in.

Jordaens! Not just Jordaens but rediscovered and hitherto unpublished Jordaens. Despite his conversion to Protestantism, I’m a fan of the Flemish baroque painter, and happy to see this depiction of my triple-patron (the apostle is my name-saint, the patron of my university, and the patron of Scotland). Jordaens continued to accept commissions for Catholic churches after his departure from the communion, a fact discussed in Xander van Eck’s Clandestine Splendor: Paintings for the Catholic Church in the Dutch Republic which I reviewed for the Weekly Standard last year.

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Portrait of Florentius Josephus van Ertborn

1805; Oil on panel, 25½ in. x 21 in.

Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s book The Leopard was composed almost solely of memorable scenes. In one of them, Don Fabrizio, the Prince of Salina, sits in a library staring at the Greuze painting La mort du juste and contemplates his own mortality. A reference in what some have called the twentieth century’s finest novel is a great honour indeed, and probably a deserved one.

Here Greuze depicts Florentius Josephus van Ertborn — a Dutch aristocrat, politician, and patron of the arts. The portrait brilliantly captures a certain youthful and brash confidence: van Ertborn was just 21 years old, while the painter was 79 and in the final year of his earthly life.

The aristocrat went on to fame and fortune — Mayor of Antwerp, Chamberlain to William I of the Netherlands, Governor of the Utrecht Province — but came to something of a tragic end. Sadly for such a patron of the visual arts, he went blind, and died childless just 56 years old. Lacking issue, Van Ertborn left 114 paintings from his collection were left to the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten in his native Antwerp.

Saloman van Ruysdael, Sailboats and a Rowboat in Coastal Waters

1661; Oil on panel, 11¾ in. x 19½ in.

So many Dutchmen deft with brush and palette, but the somewhat melancholy Saloman van Ruysdael is among my favourites. A sombre nautical scene here is brightened somewhat as, in the foreground of the painting, an out-of-view gap in the clouds lightens a path for the boat of fishermen, leading them onwards.

Parmigianino, The Emperor Charles V Receiving the World

c. 1529–1530; Oil on canvas, 68 in. x 47 in.

An interesting, if uneven, work. According to Vasari, this painting was presented to the depicted emperor by Pope Clement VII but swiftly taken back by the artist who claimed it was not yet finished. It ended up with Cardinal Ippolito de Medici, who gave it to Cardinal Ercole Gonzaga of Mantua, in whose family it remained for some time.

Winged Fame holds laurel branches aloft while the Earthly Orb is presented by an infant Hercules to the Christian Emperor. Charles V’s dominion stretched from the Philippines in the Orient to Mexico and Peru in the West, taking in Austria, Spain, Burgundy, the Netherlands, and elsewhere in between.

The subject did not sit for the portrait, but Parmigianino observed the Emperor at a number of public dinners. This might explain the somewhat slapdash rendering of the imperial visage.

Allaert van Everdingen, Fishing Boats in a Harbour

c. 1660s; Oil on canvas, 27 in. x 38⅛ in.

Dutch landscapes or seascapes or, as in this painting, combinations of the two were rarely accurate portrayals of specific places but rather amalgamations of several views arranged in a handsome fashion. The spire framed by the triangular masts in van Everdingen’s painting is the Groothoofdspoort gate tower in Dordrecht, which appears in a number of his works.

Emanuel de Witte, The Interior of the Oude Kerk, Amsterdam with a Sermon in Progress

c. 1665; Oil on canvas, 38 in. x 28½ in.

Here is one of several of de Witte’s views of the Oude Kerk in Amsterdam. As with van Everdingen, it is not the precise reproduction of reality that is important but rather the overall composition, here achieved with de Witte’s usual contrasts of light and shadow accompanied by little anecdotal details from the characters depicted.

Studio of Gérard, Portrait of Napoleon in Coronation Robes

1805; Oil on canvas, 56½ in. x 42½ in.

I’ll admit this isn’t one of the best, but I like portraits of the Corsican upstart. This is from the studio of François Gérard and based on his better 1805 portrayal of the Emperor of the French in coronation robes.

And below, a horse. Its upfront simplicity seems typically German and one gets a feeling of Biedermeier contemporaneousness.

German school, A Study of a Horse

1822; Oil on paper mounted on canvas, 13½ in. x 15½ in.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

This is quite a collection of Old Masters. I have always been fond of Flemish works, and it is good to see a superlative selection of them. Interestingly, a sacra conversazione by Titian just sold at Sotheby’s, which was a new record price for any work by that Renaissance artist.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-12306549

How very Cusackian for you to be drawn to portraits of the Corsican upstart.

Your remarks on The Leopard here prompt me to observe that you are undoubtedly blessed with the master perspective on life, and to wonder if you have ever read Luigi Barzini’s essays “The Quest for Lampedusa” and “The Aristocrats” in his collection From Caesar to the Mafia.

Interesting pieces, indeed.